The Bloody Nose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

“Did You Want Us to Wrap It up for You Sir?” the Salesman Held the Small Box Out, Waiting to See If Jackson Would Take It

After Life: Love Patrick Lee Published by Patrick Lee at Smashwords Copyright 2010 by Patrick Lee Smashwords Edition, License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. Table of Contents Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty One Chapter Twenty Two Chapter Twenty Three Chapter 1 “Did you want us to wrap it up for you sir?” The salesman held the small box out, waiting to see if Jackson would take it. When his customer did nothing, he repeated the question. “I’m sorry, what did you ask?” He knew that he heard something from the well- dressed older man who helped him pick out his purchase, but the situation was finally starting to sink in, and he drifted off as he was putting his wallet back into his pants. He had planned this for almost 6 months, and he knew that there was no going back at this point. -

Illegal, but Not Against the Rules Commentary by Shanin Specter OK

August 9, 2007 Illegal, but not against the rules Commentary By Shanin Specter OK, so Barry Bonds did it. What should we think? Many believe Bonds used steroids to break Hank Aaron's home run record, but that's only a beginning point for analysis. Here's the polestar: As legendary manager John McGraw said about baseball, "The main idea is to win. " What circumscribes this creed? Only the rules of baseball. If a runner stealing second knows the fielder's tag beat his hand to the base, but the umpire calls him safe, should he stay on the base? Yes. If an outfielder traps a fly ball, can he play it as if he caught it? Yes. The uninitiated might consider this to be fraud or immoral. But some deception is part of the game. This conduct is appropriate simply because it's not forbidden by the rules. Baseball isn't golf. There's no honor code. Yankee Alex Rodriguez's foiling a pop-up catch by yelling may have been bush league, but umpires imposed no punishment. Typical retaliation would be a pitch in the ribs in the next at-bat - assault and battery in the eyes of the law, but just part of the game of baseball. Baseball has a well-oiled response to cheating. Pitchers who scuff the ball are tossed out of that game and maybe the next one, too. Players who cork bats face a similar fate. Anyone thought to be engaged in game- fixing is banned for life. No court of public opinion or law has overturned that sentence. -

Jan-29-2021-Digital

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 64, No. 2 Friday, Jan. 29, 2021 $4.00 Innovative Products Win Top Awards Four special inventions 2021 Winners are tremendous advances for game of baseball. Best Of Show By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball Awarded By Collegiate Baseball F n u io n t c a t REENSBORO, N.C. — Four i v o o n n a n innovative products at the recent l I i t y American Baseball Coaches G Association Convention virtual trade show were awarded Best of Show B u certificates by Collegiate Baseball. i l y t t nd i T v o i Now in its 22 year, the Best of Show t L a a e r s t C awards encompass a wide variety of concepts and applications that are new to baseball. They must have been introduced to baseball during the past year. The committee closely examined each nomination that was submitted. A number of superb inventions just missed being named winners as 147 exhibitors showed their merchandise at SUPERB PROTECTION — Truletic batting gloves, with input from two hand surgeons, are a breakthrough in protection for hamate bone fractures as well 2021 ABCA Virtual Convention See PROTECTIVE , Page 2 as shielding the back, lower half of the hand with a hard plastic plate. Phase 1B Rollout Impacts Frontline Essential Workers Coaches Now Can Receive COVID-19 Vaccine CDC policy allows 19 protocols to be determined on a conference-by-conference basis,” coaches to receive said Keilitz. -

RBBA Coaches Handbook

RBBA Coaches Handbook The handbook is a reference of suggestions which provides: - Rule changes from year to year - What to emphasize that season broken into: Base Running, Batting, Catching, Fielding and Pitching By focusing on these areas coaches can build on skills from year to year. 1 Instructional – 1st and 2nd grade Batting - Timing Base Running - Listen to your coaches Catching - “Trust the equipment” - Catch the ball, throw it back Fielding - Always use two hands Pitching – fielding the position - Where to safely stand in relation to pitching machine 2 Rookies – 3rd grade Rule Changes - Pitching machine is replaced with live, player pitching - Pitch count has been added to innings count for pitcher usage (Spring 2017) o Pitch counters will be provided o See “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook - Maximum pitches per pitcher is 50 or 2 innings per day – whichever comes first – and 4 innings per week o Catching affects pitching. Please limit players who pitch and catch in the same game. It is good practice to avoid having a player catch after pitching. *See Catching/Pitching notations on the “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook. - Pitchers may not return to game after pitching at any point during that game Emphasize-Teach-Correct in the Following Areas – always continue working on skills from previous seasons Batting - Emphasize a smooth, quick level swing (bat speed) o Try to minimize hitches and inefficiencies in swings Base Running - Do not watch the batted ball and watch base coaches - Proper sliding - On batted balls “On the ground, run around. -

Describing Baseball Pitch Movement with Right-Hand Rules

Computers in Biology and Medicine 37 (2007) 1001–1008 www.intl.elsevierhealth.com/journals/cobm Describing baseball pitch movement with right-hand rules A. Terry Bahilla,∗, David G. Baldwinb aSystems and Industrial Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0020, USA bP.O. Box 190 Yachats, OR 97498, USA Received 21 July 2005; received in revised form 30 May 2006; accepted 5 June 2006 Abstract The right-hand rules show the direction of the spin-induced deflection of baseball pitches: thus, they explain the movement of the fastball, curveball, slider and screwball. The direction of deflection is described by a pair of right-hand rules commonly used in science and engineering. Our new model for the magnitude of the lateral spin-induced deflection of the ball considers the orientation of the axis of rotation of the ball relative to the direction in which the ball is moving. This paper also describes how models based on somatic metaphors might provide variability in a pitcher’s repertoire. ᭧ 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Curveball; Pitch deflection; Screwball; Slider; Modeling; Forces on a baseball; Science of baseball 1. Introduction The angular rule describes angular relationships of entities rel- ative to a given axis and the coordinate rule establishes a local If a major league baseball pitcher is asked to describe the coordinate system, often based on the axis derived from the flight of one of his pitches; he usually illustrates the trajectory angular rule. using his pitching hand, much like a kid or a jet pilot demon- Well-known examples of right-hand rules used in science strating the yaw, pitch and roll of an airplane. -

Baseball Player of the Year: Cam Collier, Mount Paran Christian | Sports | Mdjonline.Com

6/21/2021 Baseball Player of the Year: Cam Collier, Mount Paran Christian | Sports | mdjonline.com https://www.mdjonline.com/sports/baseball-player-of-the-year-cam-collier-mount-paran-christian/article_052675aa- d065-11eb-bf91-f7bd899a73a0.html FEATURED TOP STORY Baseball Player of the Year: Cam Collier, Mount Paran Christian By Christian Knox MDJ Sports Writer Jun 18, 2021 Cam Collier watches a fly ball to center during the first game of Mount Paran Christian’s Class A Private state championship Cam Collier has no shortage of tools, and he displays them all around the diamond. In 2021, the Mount Paran Christian sophomore showed a diverse pitching arsenal that left opponents guessing, home run power as a batter, defensive consistency as a third baseman and the agility of a gazelle as a runner. https://www.mdjonline.com/sports/baseball-player-of-the-year-cam-collier-mount-paran-christian/article_052675aa-d065-11eb-bf91-f7bd899a73a0.html 1/5 6/21/2021 Baseball Player of the Year: Cam Collier, Mount Paran Christian | Sports | mdjonline.com However, Collier’s greatest skill is not limited to the position he is playing at any given time. He carries a finisher’s mentality all over the field. “He wants the better, the harder situation. The more difficult the situation, the more he enjoys it,” Mount Paran coach Kyle Reese said. “You run across those (difficult) paths a lot of the time, and Cam is a guy that absolutely thrives in them. Whether he is in the batter’s box or on the mound, the game’s on the line, he wants to determine the outcome of the game. -

ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL

T HE CHILD’ S WORLD® ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL VOLUME 3: REGGIE JACKSON THROUGH OUTFIELDER T HE CHILD’ S WORLD® ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL VOLUME 3: REGGIE JACKSON THROUGH OUTFIELDER By James Buckley, Jr., David Fischer, Jim Gigliotti, and Ted Keith KEY TO SYMBOLS Throughout The Child’s World® Encyclopedia of Baseball, you’ll see these symbols. They’ll give you a quick clue pointing to each entry’s general subject area. Active Baseball Hall of Miscellaneous Ballpark Team player word or Fame phrase Published in the United States of America by The Child’s World® 1980 Lookout Drive, Mankato, MN 56003-1705 800-599-READ • www.childsworld.com www.childsworld.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Child’s World®: Mary Berendes, Publishing Director Produced by Shoreline Publishing Group LLC President / Editorial Director: James Buckley, Jr. Cover Design: Kathleen Petelinsek, The Design Lab Interior Design: Tom Carling, carlingdesign.com Assistant Editors: Jim Gigliotti, Zach Spear Cover Photo Credits: Getty Images (main); National Baseball Hall of Fame Library (inset) Interior Photo Credits: AP/Wide World: 5, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 52, 56, 57, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 70, 72, 74, 75, 78, 79, 80, 83, 75; Corbis: 18, 22, 37, 39; Focus on Baseball: 7t, 10, 11, 29, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 49, 51, 55, 58, 67, 69, 71, 76, 81; Getty Images: 54; iStock: 31, 53; Al Messerschmidt: 12, 48; National Baseball Hall of Fame Library: 6, 7b, 28, 36, 68; Shoreline Publishing Group: 13, 19, 25, 60. -

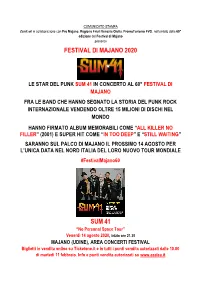

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

Personal Hitting Philosophy.Docx

PERSONAL HITTING PHILOSOPHY & WHERE YOU FIT IN THE BASEBALL LINEUP Accurately evaluating yourself to know what kind of hitter you are can be a difficult, but necessary, part of developing your personal hitting philosophy. The great thing about a baseball lineup is there is room on every team and in the big leagues for all types of hitters. Understand Your Personal Hitting Philosophy A good hitting philosophy should definitely depend on what kind of hitter you are. Are you a player that hits for a lot of power, do you try to set the table and get on base for the middle of the lineup, can you run, are you a good situational hitter, can you hit to all parts of the field or do you mostly just pull the ball. Accurately evaluating yourself and knowing what kind of hitter you are can be difficult. The great thing about baseball is there is room on every team and in the big leagues for all types of hitters. Players get in trouble when they want to be something they are not. This is fairly common and a problem most young hitters face. Everyone wants to hit homeruns. But not everyone was talented in that area. If you hit one homerun a year and most of your outs are fly balls, you are only hurting yourself. The good hitters use what they are given and use it to the best of their ability. If you can run, hit balls on the ground and utilize the bunt. If you can handle the bat, try to hit the 3-4 hole (in between 1st and 2nd base) with a runner on 1st base, to get the runner to move up to 3rd base. -

The Obituary Writer Corrie Rhoda Byrne Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 The Obituary Writer Corrie Rhoda Byrne Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Byrne, Corrie Rhoda, "The Obituary Writer" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13265. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13265 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i The obituary writer by Corrie Rhoda Byrne A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the degree MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and the Environment Program of Study Committee: David Zimmerman, Major Professor Stephen Pett Linda Shenk Susan Stewart Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................................................ii ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................iii TITLE PAGE..................................................................................................................................1