The Hunt Forthe Biggest Explosions in the Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Concrete Scales: a Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali

Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali To cite this version: Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2013, 19 (12), pp.2426-2435. 10.1109/TVCG.2013.210. hal-00851733v1 HAL Id: hal-00851733 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00851733v1 Submitted on 8 Jan 2014 (v1), last revised 8 Jan 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, and Guia Gali a b c Fig. 1. Illustrates popular representations of complex measures: (a) US Debt (Oto Godfrey, Demonocracy.info, 2011) explains the gravity of a 115 trillion dollar debt by progressively stacking 100 dollar bills next to familiar objects like an average-sized human, sports fields, or iconic New York city buildings [15] (b) Sugar stacks (adapted from SugarStacks.com) compares caloric counts contained in various foods and drinks using sugar cubes [32] and (c) How much water is on Earth? (Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Howard Perlman, USGS, 2010) shows the volume of oceans and rivers as spheres whose sizes can be compared to that of Earth [38]. -

Detection of PAH and Far-Infrared Emission from the Cosmic Eye

Accepted for publication in ApJ A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 08/22/09 DETECTION OF PAH AND FAR-INFRARED EMISSION FROM THE COSMIC EYE: PROBING THE DUST AND STAR FORMATION OF LYMAN BREAK GALAXIES B. Siana1, Ian Smail2, A. M. Swinbank2, J. Richard2, H. I. Teplitz3, K. E. K. Coppin2, R. S. Ellis1, D. P. Stark4, J.-P. Kneib5, A. C. Edge2 Accepted for publication in ApJ ABSTRACT ∗ We report the results of a Spitzer infrared study of the Cosmic Eye, a strongly lensed, LUV Lyman Break Galaxy (LBG) at z =3.074. We obtained Spitzer IRS spectroscopy as well as MIPS 24 and 70 µm photometry. The Eye is detected with high significance at both 24 and 70 µm and, when including +4.7 11 a flux limit at 3.5 mm, we estimate an infrared luminosity of LIR = 8.3−4.4 × 10 L⊙ assuming a magnification of 28±3. This LIR is eight times lower than that predicted from the rest-frame UV properties assuming a Calzetti reddening law. This has also been observed in other young LBGs, and indicates that the dust reddening law may be steeper in these galaxies. The mid-IR spectrum shows strong PAH emission at 6.2 and 7.7 µm, with equivalent widths near the maximum values observed in star-forming galaxies at any redshift. The LP AH -to-LIR ratio lies close to the relation measured in local starbursts. Therefore, LP AH or LMIR may be used to estimate LIR and thus, star formation rate, of LBGs, whose fluxes at longer wavelengths are typically below current confusion limits. -

Close-Up View of a Luminous Star-Forming Galaxy at Z = 2.95 S

Close-up view of a luminous star-forming galaxy at z = 2.95 S. Berta, A. J. Young, P. Cox, R. Neri, B. M. Jones, A. J. Baker, A. Omont, L. Dunne, A. Carnero Rosell, L. Marchetti, et al. To cite this version: S. Berta, A. J. Young, P. Cox, R. Neri, B. M. Jones, et al.. Close-up view of a luminous star- forming galaxy at z = 2.95. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2021, 646, pp.A122. 10.1051/0004-6361/202039743. hal-03147428 HAL Id: hal-03147428 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03147428 Submitted on 19 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A&A 646, A122 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202039743 & c S. Berta et al. 2021 Astrophysics Close-up view of a luminous star-forming galaxy at z = 2.95? S. Berta1, A. J. Young2, P. Cox3, R. Neri1, B. M. Jones4, A. J. Baker2, A. Omont3, L. Dunne5, A. Carnero Rosell6,7, L. Marchetti8,9,10 , M. Negrello5, C. Yang11, D. A. Riechers12,13, H. Dannerbauer6,7, I. -

Fast Solar Wind Monitor (BMSW): Description and First Results

Space Sci Rev (2013) 175:165–182 DOI 10.1007/s11214-013-9979-4 Fast Solar Wind Monitor (BMSW): Description and First Results Jana Šafránková · Zdenekˇ Nemeˇ cekˇ · Lubomír Prechˇ · Georgy Zastenker · Ivo Cermákˇ · Lev Chesalin · Arnošt Komárek · Jakub Vaverka · Martin Beránek · Jiríˇ Pavl˚u · Elena Gavrilova · Boris Karimov · Arkadii Leibov Received: 4 September 2012 / Accepted: 19 March 2013 / Published online: 6 April 2013 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 Abstract Monitoring of solar wind parameters is a key problem of the Space Weather pro- gram. The paper presents a description of a novel fast solar wind monitor (Bright Monitor of the Solar Wind, BMSW) and the first results of its measurements of plasma moments with a time resolution ranging from seconds to 31 ms. The method of the fast monitoring is based on simultaneous measurements of the total ion flux and ion integral energy spectrum by six nearly identical Faraday cups (FCs). Three of them are dedicated to determination of the ion flow direction, whereas other three equipped with control grids supplied by a re- tarding potential are used for a determination of the density, temperature, and speed of the plasma flow. The paper introduces not only the measuring methods, the FCs design, and modes of operation, but brings the examples of time series of measurements and their com- parison with the observations of other spacecraft as well as the first results of an analysis of frequency spectra of solar wind fluctuations within the ion kinetic scale, examples of rapid measurements at the ramp of an interplanetary shock and investigations of fast variations of alpha particle content. -

Ast110fall2015-Labmanual.Pdf

2015/2016 (http://astronomy.nmsu.edu/astro/Ast110Fall2015.pdf) 1 2 Contents 1IntroductiontotheAstronomy110Labs 5 2TheOriginoftheSeasons 21 3TheSurfaceoftheMoon 41 4ShapingSurfacesintheSolarSystem:TheImpactsofCometsand Asteroids 55 5IntroductiontotheGeologyoftheTerrestrialPlanets 69 6Kepler’sLawsandGravitation 87 7TheOrbitofMercury 107 8MeasuringDistancesUsingParallax 121 9Optics 135 10 The Power of Light: Understanding Spectroscopy 151 11 Our Sun 169 12 The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram 187 3 13 Mapping the Galaxy 203 14 Galaxy Morphology 219 15 How Many Galaxies Are There in the Universe? 241 16 Hubble’s Law: Finding the Age of the Universe 255 17 World-Wide Web (Extra-credit/Make-up) Exercise 269 AFundamentalQuantities 271 BAccuracyandSignificantDigits 273 CUnitConversions 274 DUncertaintiesandErrors 276 4 Name: Lab 1 Introduction to the Astronomy 110 Labs 1.1 Introduction Astronomy is a physical science. Just like biology, chemistry, geology, and physics, as- tronomers collect data, analyze that data, attempt to understand the object/subject they are looking at, and submit their results for publication. Along thewayas- tronomers use all of the mathematical techniques and physics necessary to understand the objects they examine. Thus, just like any other science, a largenumberofmath- ematical tools and concepts are needed to perform astronomical research. In today’s introductory lab, you will review and learn some of the most basic concepts neces- sary to enable you to successfully complete the various laboratory exercises you will encounter later this semester. When needed, the weekly laboratory exercise you are performing will refer back to the examples in this introduction—so keep the worked examples you will do today with you at all times during the semester to use as a refer- ence when you run into these exercises later this semester (in fact, on some occasions your TA might have you redo one of the sections of this lab for review purposes). -

Annexe: Summary of Soviet and Russian Space Science Missions

Contents Introduction by the authors ..................................... ix Acknowledgments ............................................ xi Glossary .................................................. xiii Terminological and translation notes ..............................xv Reference notes .............................................xvii List of tables ............................................... xix List of illustrations ......................................... xxiii List of figures .............................................xxvii 1 Early space science ........................................... 1 Space science by balloon....................................... 3 Scientific flights into the atmosphere: the Akademik series..............14 Scientific test flights with animals ................................20 The idea of a scientific Earth satellite .............................23 Scientific objectives of the first Earth satellites . ....................25 Key people .................................................25 Instead, Prosteishy Sputnik .....................................27 PS2......................................................29 Object D: the first large scientific satellite in orbit....................33 Early space science: what was learned? ............................37 References .................................................39 2 Deepening our understanding ....................................43 Following Sputnik: the MS series ................................43 Cosmos 5 and Starfish: introducing Yuri Galperin -

12 Strong Gravitational Lenses

12 Strong Gravitational Lenses Phil Marshall, MaruˇsaBradaˇc,George Chartas, Gregory Dobler, Ard´ısEl´ıasd´ottir,´ Emilio Falco, Chris Fassnacht, James Jee, Charles Keeton, Masamune Oguri, Anthony Tyson LSST will contain more strong gravitational lensing events than any other survey preceding it, and will monitor them all at a cadence of a few days to a few weeks. Concurrent space-based optical or perhaps ground-based surveys may provide higher resolution imaging: the biggest advances in strong lensing science made with LSST will be in those areas that benefit most from the large volume and the high accuracy, multi-filter time series. In this chapter we propose an array of science projects that fit this bill. We first provide a brief introduction to the basic physics of gravitational lensing, focusing on the formation of multiple images: the strong lensing regime. Further description of lensing phenomena will be provided as they arise throughout the chapter. We then make some predictions for the properties of samples of lenses of various kinds we can expect to discover with LSST: their numbers and distributions in redshift, image separation, and so on. This is important, since the principal step forward provided by LSST will be one of lens sample size, and the extent to which new lensing science projects will be enabled depends very much on the samples generated. From § 12.3 onwards we introduce the proposed LSST science projects. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but should serve as a good starting point for investigators looking to exploit the strong lensing phenomenon with LSST. -

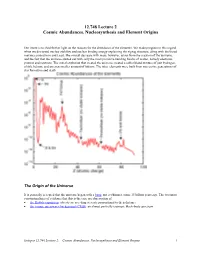

12.748 Lecture 2 Cosmic Abundances, Nucleosynthesis and Element Origins

12.748 Lecture 2 Cosmic Abundances, Nucleosynthesis and Element Origins Our intent is to shed further light on the reasons for the abundance of the elements. We made progress in this regard when we discussed nuclear stability and nuclear binding energy explaining the zigzag structure, along with the broad maxima around Iron and Lead. The overall decrease with mass, however, arises from the creation of the universe, and the fact that the universe started out with only the most primitive building blocks of matter, namely electrons, protons and neutrons. The initial explosion that created the universe created a rather bland mixture of just hydrogen, a little helium, and an even smaller amount of lithium. The other elements were built from successive generations of star formation and death. The Origin of the Universe It is generally accepted that the universe began with a bang, not a whimper, some 15 billion years ago. The two most convincing lines of evidence that this is the case are observation of • the Hubble expansion: objects are receding at a rate proportional to their distance • the cosmic microwave background (CMB): an almost perfectly isotropic black-body spectrum Isotopes 12.748 Lecture 2: Cosmic Abundances, Nucleosynthesis and Element Origins 1 In the initial fraction of a second, the temperature is so hot that even subatomic particles like neutrons, electrons and protons fall apart into their constituent pieces (quarks and gluons). These temperatures are well beyond anything achievable in the universe since. As the fireball expands, the temperature drops, and progressively higher-level particles are manufactured. By the end of the first second, the temperature has dropped to a mere billion degrees or so, and things are starting to get a little more normal: electrons, neutrons and protons can now exist. -

Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Is the Largest Region in the Russian Federation and One of the Richest in Natural Resources

Investor's Guide to the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is the largest region in the Russian Federation and one of the richest in natural resources. Needless to say, the stable and dynamic development of Yakutia is of key importance to both the Far Eastern Federal District and all of Russia…” President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin “One of the fundamental priorities of the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is to develop comfortable conditions for business and investment activities to ensure dynamic economic growth” Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Egor Borisov 2 Contents Welcome from Egor Borisov, Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 5 Overview of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 6 Interesting facts about the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 7 Strategic priorities of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) investment policy 8 Seven reasons to start a business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 10 1. Rich reserves of natural resources 10 2. Significant business development potential for the extraction and processing of mineral and fossil resources 12 3. Unique geographical location 15 4. Stable credit rating 16 5. Convenient conditions for investment activity 18 6. Developed infrastructure for the support of small and medium-sized enterprises 19 7. High level of social and economic development 20 Investment infrastructure 22 Interaction with large businesses 24 Interaction with small and medium-sized enterprises 25 Other organisations and institutions 26 Practical information on doing business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 27 Public-Private Partnership 29 Information for small and medium-sized enterprises 31 Appendix 1. -

Jacques Tiziou Space Collection

Jacques Tiziou Space Collection Isaac Middleton and Melissa A. N. Keiser 2019 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series : Files, (bulk 1960-2011)............................................................................... 4 Series : Photography, (bulk 1960-2011)................................................................. 25 Jacques Tiziou Space Collection NASM.2018.0078 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: Jacques Tiziou Space Collection Identifier: NASM.2018.0078 Date: (bulk 1960s through -

ASTR110G Astronomy Laboratory Exercises C the GEAS Project 2020

ASTR110G Astronomy Laboratory Exercises c The GEAS Project 2020 ASTR110G Laboratory Exercises Lab 1: Fundamentals of Measurement and Error Analysis ...... ....................... 1 Lab 2: Observing the Sky ............................... ............................. 35 Lab 3: Cratering and the Lunar Surface ................... ........................... 73 Lab 4: Cratering and the Martian Surface ................. ........................... 97 Lab 5: Parallax Measurements and Determining Distances ... ....................... 129 Lab 6: The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram and Stellar Evolution ..................... 157 Lab 7: Hubble’s Law and the Cosmic Distance Scale ........... ..................... 185 Lab 8: Properties of Galaxies .......................... ............................. 213 Appendix I: Definitions for Keywords ..................... .......................... 249 Appendix II: Supplies ................................. .............................. 263 Lab 1 Fundamentals of Measurement and Error Analysis 1.1 Introduction This laboratory exercise will serve as an introduction to all of the laboratory exercises for this course. We will explore proper techniques for obtaining and analyzing data, and practice plotting and analyzing data. We will discuss a scientific methodology for conducting exper- iments in which we formulate a question, predict the behavior of the system based on likely solutions, acquire relevant data, and then compare our predictions with the observations. You will have a chance to plan a short experiment, -

1. State of the Magnetosphere

VOL. 78, NO. 16 3OURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH 3UNE 1, 1973 SatelliteStudies of MagnetosphericSubstorms on August15, 1968 1. Stateof the Magnetosphere R. L. M CPHERRON Department o] Planetary and SpaceScience and Institute o] Geophysicsand Planetary Physics University o] California, Los Angeles,California 90024 The sequenceof eventsoccurring throughou.t the magnetosphereduring a substormhas not been precisely determined. This paper introduces a collection.of papers that attempts to establish this sequencefor two substormson August 15, 1968. Data from a wide variety of sourcesare used, the major emphasisbeing changesin the magnetic field. In this paper we use ground magnetograms to determine the onset times of two substorms that occurred while the Ogo 5 satellite was inbound on the midnight meridian through the cusp region of the geomagnetictail (the region of rapid changefrom taillike to dipolar field). We concludethat at least two worldwide substormexpansions were precededby growth phases.Probable begin- nings of these phaseswere at 0330 and 0640 UT. However, the onset of the former growth phase was partially obscuredby the effects of a preceding expansionphase around 0220 and a possible localized event in the auroral zone near 0320 UT. The onsets of the cor- respondingexpansion phases were 0430 and 0714 UT. Further support for these determina- tions is provided by data discussedin the subsequentnotes. The precise sequenceof events that occurs Ogo 5 in the near tail, and ATS I at syn- during a magnetosphericsubstorm has not been chronousorbit. Solar wind plasma parameters established.Among the reasons for this are were measured by Vela 4A. Magnetospheric lack of consistencyin the definition of sub- convection is inferred from a combination of storm onset and the wide variability of suc- plasmapauseobservations on Ogo 4 and 5 in cessivesubstorms.