EG 202 417 V1.1.2 (2006-12) ETSI Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multimedia Messaging Service : an Engineering Approach To

Multimedia Messaging Service Multimedia Messaging Service An Engineering Approach to MMS Gwenael¨ Le Bodic Alcatel, France Copyright 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Other Wiley Editorial Offices John Wiley & Sons Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA Jossey-Bass, 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741, USA Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Boschstr. 12, D-69469 Weinheim, Germany John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd, 33 Park Road, Milton, Queensland 4064, Australia John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2 Clementi Loop #02-01, Jin Xing Distripark, Singapore 129809 John Wiley & Sons Canada Ltd, 22 Worcester Road, Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada M9W 1L1 Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. -

Mobile Connection Explorer for Windows Introduction and Features

Mobile Connection Explorer 15 May 2013 for Windows Version 21 Introduction and Features Public version Gemfor s.r.o. Tyršovo nám. 600 252 63 Roztoky Czech Republic Gemfor s.r.o. Tyršovo nám. 600 252 63 Roztoky Czech Republic e-mail: [email protected] Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 History ......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Scope ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Abbreviations ......................................................................................................... 4 3. Solution .................................................................................................................. 5 4. Specification ........................................................................................................... 5 5. Product description ................................................................................................. 9 5.1 Supported operating systems ....................................................................... 9 5.2 Hardware device connections ....................................................................... 9 5.3 Network connection types ............................................................................. 9 5.4 Customizable graphical skin ...................................................................... -

T-Mobile Communication Centre User Manual Content

T-Mobile Communication Centre User manual Content 1. Introduction 3 2. Hardware and Software Requirements 4 3. Software Installation and Setup of Access through Internet 4G Service 5 4. Software Installation and Setup of Access through GPRS/EDGE 7 5. Main Window 10 6. Connection and Disconnection 11 7. WLAN Settings 12 8. Sending SMS 13 9. Network Selection and Logging-Off the Network 14 10. Equipment Management 15 11. APN Management 16 12. For Advanced Users 19 13. Abbreviations 20 3 1. Introduction T-Mobile Communication Centre allows easy setup of Internet The software supports all GPRS/EDGE telephones sold through the access and also access to the Internet from your computer using sales network of T-Mobile Czech Republic a.s. The list of supported mobile data transmission provided within the framework of handsets/devices is displayed during software installation and also Internet 4G, GPRS/EDGE, and WLAN services. at any time during a new device installation (see step 7 in Section 4 below). Should your device be missing in the list, it is possible to If you decide to use the T-Mobile Communication Centre, you do not upgrade the software by clicking on Aktualizace programu (Software have to spend time by installing the modem and configuring your Update) in Nastavení (Settings) menu available after clicking on the connection. The software does everything for you. It is only enough to button with key symbol (the link will take you to the page from which connect the modem or telephone to your computer using a cable, the latest version of T-Mobile Communication Centre can be Bluetooth, infrared port, or insert a suitable PCMCIA card into your downloaded). -

CDMA Přichází Konečně Rychlý Mobilní Internet Recenze Mobilů Siemens S65 Motorola V80 Motorola E398 Alcatel OT 756 Nokia 3220

O MOBILECH VÍME VŠE O UŽITEČNÉ RADY A TIPY O SOUTĚŽ: 3 × LUXUSNÍ SAMSUNG SGH-E800 39 Kč (59 Sk) mobility 9/2004 9/2004 vyšlo 9. září 2004, ročník VI www.mobilmania.cz MOBILY kocour GARFIELD na displeji S RÁDIEM mobilu 18 telefonů v přehledu CDMA přichází konečně rychlý mobilní internet recenze mobilů Siemens S65 Motorola V80 Motorola E398 Alcatel OT 756 Nokia 3220 duel Samsung SGH-E800 Siemens SL65 t nové ceny za volání Oskar a T-Mobile s novými tarify obsah mobility 9/2004 3 obsah 4 fotomobility pošlete fotku z mobilu a vyhrajte 6 první pohledy krátké představení mobilních telefonů Motorola Razr V3 a Siemens SK65 8 mobilitky obrazové pohledy do mobilní budoucnosti, zajímavosti a postřehy ze světa mobilů 13 mobile news nejnovější mobilní služby operátorů, mobilní novinky 30 zajímavosti ze Slovenska mobilních dnů Z Eurotelu možná bude Všichni máme mobil. Z úda- Vodafone. Tato nadnárodní jů o počtu zákazníků, které skupina totiž oficiálně proje- uveřejnili mobilní operátoři, vila zájem o koupi Českého vyplývá, že počet karet SIM Telecomu. Jelikož Vodafone je v České republice překročil čistě mobilní operátor, dá se hranici deseti milionů. Pene- očekávat, že si ponechá pouze trace se tak vyhoupla na světo- 18 mobil na rádiových vlnách Eurotel a Český Telecom ob- vě ojedinělou hodnotu 98,7 %. jaké jsou možnosti radiopřijímačů v mobilních telefonech ratem prodá někomu jinému. Ve skutečnosti to ale není tak Ve hře je například Deutsche horké. Řada lidí má více čísel nejrychlejší mobilní internet Telecom, který vlastní mimo a v celkovém počtu jsou navíc 24 podrobné představení služby Eurotel Data Express jiné i český T-Mobile. -

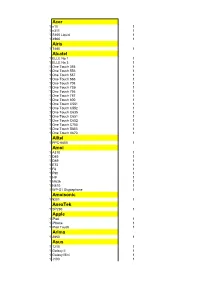

Acer Airis Alcatel Alltel Amoi Amoisonic Anextek Apple Arima

Acer 1 n10 1 1 n311 1 1 S100 Liquid 1 1 X960 1 Airis 1 T480 1 Alcatel 1 ELLE No 1 1 1 ELLE No 3 1 1 One Touch 355 1 1 One Touch 556 1 1 One Touch 557 1 1 One Touch 565 1 1 One Touch 708 1 1 One Touch 735i 1 1 One Touch 756 1 1 One Touch 757 1 1 One Touch 800 1 1 One Touch C551 1 1 One Touch C552 1 1 One Touch C635 1 1 One Touch C651 1 1 One Touch C652 1 1 One Touch C750 1 1 One Touch S853 1 1 One Touch V670 1 Alltel 1 PPC-6800 1 Amoi 1 A310 1 1 D85 1 1 D89 1 1 E72 1 1 F8 1 1 F90 1 1 H9 1 1 M636 1 1 N810 1 1 WP-S1 Skypephone 1 Amoisonic 1 9201 1 AnexTek 1 SP230 1 Apple 1 iPad 1 1 iPhone 1 1 iPod Touch 1 Arima 1 2850 1 Asus 1 1210 1 1 Galaxy II 1 1 Galaxy Mini 1 1 J100 1 1 J101 1 1 J102 1 1 M303 1 1 M530w 1 1 M930 1 1 P320 1 1 P505 1 1 P525 1 1 P526 1 1 P527 1 1 P550 1 1 P552 1 1 P735 1 1 P750 1 1 V80 1 AT&T 1 8900 Tilt 1 1 8925 Tilt 1 Audiovox 1 CDM-8450 1 1 CDM-8450SP 1 1 CDM-8455 1 1 CDM-8615 1 1 CDM-8900 1 1 CDM-8910 1 1 CDM-8912 1 1 CDM-8915 1 1 CDM-8920 1 1 CDM-8930 1 1 PM-8912 1 1 PM-8920 1 1 PPC-6600 / PPC-6601 1 1 PPC-6700 1 1 SMT-5600 1 1 VI600 1 BenQ 1 A500 1 1 A5001 1 1 A520 1 1 CL71 1 1 E72 1 1 E81 1 1 M315 1 1 M350 1 1 M580A 1 1 Morpheus 1 1 P30 1 1 P50 1 1 S660C 1 1 S668C 1 1 S670C 1 1 S680C 1 1 S700 1 1 S7001 1 1 S82 1 1 S830C 1 1 U700 1 1 Z2 1 BenQ-Siemens 1 C81 1 1 C81F 1 1 E71 1 1 EF51 1 1 EF81 1 1 EF91 1 1 EL71 1 1 M81 1 1 P51 1 1 S68 1 1 S80 1 1 S81 1 Bird 1 D660 1 1 E810 1 1 S689 1 1 SC01 1 1 SC24 1 1 V007 1 BlackBerry 1 7100g 1 1 7100i 1 1 7100r 1 1 7100t 1 1 7100v 1 1 7100x 1 1 7105t 1 1 7130c 1 1 7130e 1 1 7130g -

Telecom Magazin 2005 6 Hun.Pdf 19095 KB Magazin

SZERKESZTÕI LEVÉL Telekommunikációs magazin Megjelenik havonta Kiadja: Telecom Press Bt. Felelôs kiadó: Várnagy Attila fõszerkesztõ A kiadó ügyvezetô igazgatója Fôszerkesztô: Várnagy Attila Vezetõszerkesztô: Kollár Sándor ZENE, FOTÓ ÉS VIDEÓ Lapigazgató: alán már elcsépeltnek tûnik, hogy a multimédia egyre inkább összekapcsolódik a Czinege Erika mobiltelefonokkal: manapság csak a legegyszerûbb, belépõ modellekbõl hiány- Szerkesztô: T zik a kamera, és egyre több mobilkészülékbe kerül MP3-lejátszó, megapixeles Steierlein Péter kamera és videofelvevõ funkció. Tulajdonképpen minden gyártó a mobil multimédia irá- ([email protected]) nyába halad, különbség leginkább abban tapasztalható, hogy mindezt milyen tempóban Hírszerkesztô: teszik, és milyen módon kommunikálják. Sándor Gergely Az idei CeBIT-en legmarkánsabban talán a Samsung kürtölte világgá, hogy õk bizony ([email protected]) nagy hangsúlyt fognak fektetni a multimédiás szolgáltatásokra: bemutatták a merevle- Tördelõszerkesztô: mezzel ellátott, MP3-lejátszós mobiltelefonjukat, illetve a 3, 5 és 7 megapixeles kamerá- Juhász Gergõ val felvértezett modelljeikkel is megismerkedhetett a nagyközönség. Várnagy Zsolt A Sony Ericsson sem volt rest: 2 megapixeles, MP3-lejátszós, bõvíthetõ memóriájú Korrektúra: modellekkel próbálta felkelteni a svéd-japán vállalat a nagyérdemû érdeklõdését. A Kármán Tamara W800-as modellt egyenesen mobil walkman névre keresztelték a marketingesek. A Nokia háza táján viszonylagos csend uralkodott, hiszen nem találtunk a cég stand- Fotók: Steierlein Péter ján igazán ütõs, korábban be nem mutatott újdonságot, ami némi csalódást jelentett, is- merve a piacvezetõ fejlesztõmérnökeinek kreativitását. Gondoljunk csak arra, hogy a Munkatársaink: finnek építettek elõször kamerát GSM-telefonba, õk vitték sikerre a Symbian S60 Balázs Ernõ okostelefonokat, és a Nokia nevéhez fûzõdik a kommunikátorkategória megteremtése is. Budai Péter Dén Mátyás András Szóval valami nagy durranást reméltünk a finnektõl. -

Kabel Irda Bluetooth Paměť Telefonu Paměť SIM Karty Alcatel One Touch 535 Ano

Podporované připojení Načítání kontaktů Telefon kabel IrDA bluetooth paměť telefonu paměť SIM karty podpora SMS podpora MMS Alcatel One Touch 535 Ano Ano - - Ano Ano - Alcatel One Touch 715 Ano Ano - - Ano Ano - Alcatel One Touch 735 Ano Ano - - Ano Ano - Ericsson R520m Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ericsson T39m Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ericsson T65 Ano - - Ano Ano Ano Ano Ericsson T68 Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Ano Huawei E620 Ano - - Ano Ano Ano Ano LG C1200 Ano - - Ano Ano Ano Ano LG C2200 Ano - - Ano Ano Ano Ano LG C3320 Ano - - Ano Ano Ano Ano LG L5100 Ano Ano - Ano Ano Ano Ano Motorola A1000 Ano - Ano - Ano - Ano Motorola C385 Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola C450 Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola C550 Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola E1 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola E1070 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola E398 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola E550 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola L2 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola L6 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola L7 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola L7v Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola T720i Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola Timeport 280 Ano Ano - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola U6 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V186 Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V235 Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V3 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V300 Ano - - Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V360 Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V3i Ano - Ano Ano Ano omezeno 1) Ano Motorola V3iv -

Liste Eop Au 07 03 21

LISTE DE PRIX ECOL-O-POINT AU 21 MARS 2007 1 Point = 0,10 Cts CARTOUCHES JET D'ENCRE NOTE: Cette Liste est fournie à titre d'information seulement - Les informations indiquées peuvent varier à tout moment APPLE Cartridge Reference Points Apple M4609G/A or BC05 5 Apple Stylewriter M8052G/A or BC01 2 Apple Stylewriter II / 200 / 1500 M8041G/C or BC02 4 CALCOMP Cartridge Reference Points Calcomp IH 205 2 Calcomp TechJet 5500 Black IH 955B 1 Calcomp TechJet 5500 Cyan IH 955C 1 Calcomp TechJet 5500 Magenta IH 955M 1 Calcomp TechJet 5500 Yellow IH 955Y 1 CANON Cartridge Reference Points Canon BJ-10 / BJ-5 / BJ-20 BC-01 2 Canon BJ100 / 200 / 220 / 230 / BJC-150 / 210 / 240 BC-02 4 Canon BJC-150 / 210 / 241 BC-05 5 Canon BJC-150 / 210 / 242 BC-06 3 Canon BJC 4000 / 4100 / 4300 / 4400 / 5000 (black cartridge) BC-20 2 Canon BC-22 2 Canon BC-23 2 Canon B140 / 150 / 160 / 170 / 310 / 320 / 340 / 360 BX2 3 Canon B100 / 110 / Multipass 10 / 800 BX3 4 Canon B230C BX20 2 Canon PG40 Black PG 40 B 6 Canon CL41 Couleur CL 41 Couleur 6 Canon CL8 CL 8 2 Canon PG50 PG 50 B 6 Canon CL51 CL 51 Couleur 6 DELL Cartridge Reference Points Dell DEI 7Y743 6 Dell DEI 7Y745 6 Dell DEI TO529 6 Dell DEI TO530 6 Dell J5566 6 Dell J5567 6 Dell Black M 4640 6 Dell Couleur M 4646 6 Dell Black (J740) TO 601 5 Dell Couleur (J740) TO 602 5 Dell Black (5878) TO 629 5 HEWLETT PACKARD Cartridge Reference Points Hewlett Packard Black 21 9351A 5 Hewlett Packard Couleur 22 9352A 6 Hewlett Packard gris photo 59 9359E 5 Hewlett Packard 9365A 6 Hewlett Packard gris photo 100 9368A 5 -

Report for Ofcom on the Value of Ultra Wide Band Personal Area Networking Services to the United Kingdom

Value of UWB Personal Area Networking Services to the United Kingdom Final Report for Ofcom This report was commissioned by Ofcom to provide an independent analysis of the costs and benefits which are likely to be associated with the deployment of UWB technology in the United Kingdom, in order to assist Ofcom in its development of policy in this area. The assumptions, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this report are entirely those of Mason and DotEcon and should not be attributed to Ofcom. Mason Communications Ltd 20-23 Greville Street London EC1N 8SS England Tel: +44 (0) 20 7336 8255 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7336 8256 e-mail: [email protected] www.mason.biz DotEcon Ltd 105-106 New Bond Street London W1S 1DN ENGLAND TEL: +44 (0) 20 7870 3800 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7870 3811 www.dotecon.com November 2004 FINAL REPORT FOR OFCOM VALUE OF UWB PERSONAL AREA NETWORKING SERVICES TO THE UNITED KINGDOM MASON COMMUNICATIONS LTD 20-23 GREVILLE STREET, LONDON EC1N 8SS. ENGLAND TEL: +44 (0) 20 7336 8255 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7336 8256 e-mail: [email protected] www.mason.biz DOTECON LIMITED 105-106 NEW BOND STREET, LONDON W1S 1DN, ENGLAND TEL: +44 (0)20 7870 3000 FAX +44 (0)20 7870 3811 www.dotecon.com CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................3 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................10 1.1 Study Objectives......................................................................................................10 -

Alcatel ELLE-N1 Alcatel Mandarina Duck Alcatel One Touch 355 Alcatel

Alcatel ELLE-N1 LG F2400 LG KP320 Alcatel Mandarina Duck LG F2410 LG KP500 Alcatel One Touch 355 LG F9100 LG KP502 Alcatel One Touch 535 LG G1600 LG KP502 Alcatel One Touch 556/557/565 LG G3100 LG KS360 Alcatel One Touch 756/757 LG G4015 LG KT520 Alcatel One Touch C550 LG G4020 LG KT520 Alcatel One Touch C551 LG G5300i LG KU250 Alcatel One Touch C552 LG G5400 LG KU380 Alcatel One Touch C651 LG G5500 LG KU385 Alcatel One Touch C652 LG G7050 LG KU450 Alcatel One Touch C701 LG G7070 LG KU730 Alcatel One Touch C750 LG G7100 LG KU800 Alcatel One Touch C825 LG G7110 LG KU970 Alcatel One Touch S853 LG GB170 LG KU990 Alcatel OT-363 LG GB190 LG L1100 Alcatel OT-708 LG GB220 LG L1150 Alcatel OT-C717 LG GB230 LG L1200 Alcatel OT-S218 LG GB270 LG L1400 Alcatel OT-S621 LG GC900 Viewty 2 LG L3100 Alcatel OT-V570 LG GD330 LG L343i Alcatel OT-V770 LG GD350 LG L600v Apple iPhone LG GM200 LG LG-KF900 BenQ M300 LG GS290 LG LG-KM900 BenQ Morpheus LG GT350 LG M4410 BenQ Nike1 S660C LG GU230 LG M6100 BenQ-Siemens EF61 LG KC550 LG P7200 BenQ-Siemens EL71 LG KC560 LG S5200 Fly 2080 LG KC910 LG T5100 Fly MC120 LG KC910 LG U250 Fly MX300 LG KE260 LG U300 Gionee I9 LG KE500 LG U450 HTC Google Nexus One LG KE770 LG U8110 HTC Hermes LG KE800 LG U8120 HTC Hero LG KE850 LG U8130 HTC iPAQ 510 LG KE970 LG U8138 HTC Magic LG KF300 LG U8150 HTC P3300 LG KF310 LG U8180 HTC P3600 Trinity LG KF510 LG U8330 HTC Touch HD T8282 LG KF600 LG U8360 Huawei U626 LG KF700 LG U8380 Huawei Vodafone Huawei U1280 LG KF750 LG U8500 I-Mobile 902 LG KG120 LG U8550 Lenovo i921 LG KG130 LG -

Prvi U Telekomunikacijama I Multimediji Prvi U Telekomunikacijama Broj #100

www.mobil.hr I cafe.mobil.hr #100 PRVI U TELEKOMUNIKACIJAMA I MULTIMEDIJI BROJ #100 | LIPANJ / JUNE 2008. | GODINA X. | CIJENA 25 kn | 3,5 € / 6,5 KM / 160 DIN MOBIL(MEDIA) -OD1DO100/LGHB620MOTOROLAROKRE8SAMSUNGSGH-U900SOULJAMOS506HCS /100 3/NADT535BUGOVI HZ TELKAČI / PODEŠAVANJE TV-A / KAKO DOHDSADRŽAJA/TESTLCDIPLAZMATV-A /KAKO TV-A /PODEŠAVANJE HZ TELKAČI Omot_100_proba.indd 1 29.5.2008 1:09:26 Omot_100_proba.indd 2 29.5.2008 1:09:31 RADAR TELEKOMUNIKACIJE MULTIMEDIJA INFORMATIKA LIFESTyLE M.INFO .01 .02 .03 .04 .05 .06 WWW.MOBIL.HR | CAFE.MOBIL.HR .100 | 06.2008. 3 Naslovnica Mobil #1 (1.0).indd 3 28.5.2008 17:25:29 Uvodnik Impresum Mobil - magazin o mobilnim Poštovani, komunikacijama Glavni urednik: Pred sobom držite prvi broj magazina iskljuivo posveenog mobilnim komunikacijama Saša Or$i svih vrsta. Dulje je vrijeme u nas prisutna težnja stihijskog pisanja o ovoj problematici. Zamjenik glavnog urednika: Dosta tiskovina povremeno odvoji pokoju stranicu za opise novih GSM ureaja ili DECT Davor Petri telefona no sustavno praenje mobilne telefonije do sada je bilo zanemareno. Ureivaki kolegij: Slaven Devlin, Mario Duki , Svjetska iskustva govore da kritina masa od preko 200.000 korisnika mobilnih telefona Zvonko Pavleti , Davor Petri , zadovoljava sve uvjete neophodne za izdavanje ovakvog magazina. Saša Or$i , Darko Sko$ir S druge pak strane inozemne se izdavake kue ne bore esto s našim problemima: dugim rokovima naplate, problematinim potraživanjima, optereujuim nametima i Tehnika podrška: Komteh d.o.o. porezima... Trg sportova 11 Usprkos svemu odluili smo tržištu ponuditi magazin koji e kvalitetno progovoriti o Fotograf: Božidar Prezelj problemima koji mue prosjenog korisnika mobilnog telefona. -

Universal Mega-Box - 252 Cables PROMOTION

GSM-Support ul. Bitschana 2/38, 31-420 Kraków, Poland mobile +48 608107455, NIP PL9451852164 REGON: 120203925 www.gsmsupport.eu Universal Mega-Box - 252 cables PROMOTION Added FULL unlock Nokia DCT4+ RSA (internet connection required) - NOKIA 1110i RH-93 - NOKIA 1112b RH-92 - NOKIA 1200 RH-99 - NOKIA 1200 RH-100 - NOKIA 1202 RH-112 - NOKIA 1208 RH-105 - NOKIA 1208b RH-106 - NOKIA 1209 RH-105 - NOKIA 1600b RH-66 - NOKIA 1661 RM-305 - NOKIA 1662 - NOKIA 1650 RM-305 - NOKIA 1680 Classic RM-394 - NOKIA 1680 Classic-2b RM-490 - NOKIA 2220 Slide RM-590 - NOKIA 2310 RM-189 - NOKIA 2320 Classic RM-514 - NOKIA 2320 Classic-2b RM-515 - NOKIA 2323 CLassic RM-543 - NOKIA 2330 Classic RM-512 - NOKIA 2600 RH-60 - NOKIA 2600a RH-60 - NOKIA 2600 Classic RM-340 - NOKIA 2610 RH-86 - NOKIA 2610b RH-87 - NOKIA 2626 RM-291 - NOKIA 2630 RM-298 - NOKIA 2630b RM-299 - NOKIA 2660 RM-292 - NOKIA 2660b RM-293 - NOKIA 2680 Slide RM-392 - NOKIA 2680 Slide-2b RM-500 - NOKIA 2720 Fold RM-519 - NOKIA 2760 RM-258 - NOKIA 2760b RM-259 - NOKIA 2760h RM-391 - NOKIA 5000 RM-362 - NOKIA 5030 XM RM-524 - NOKIA 6030b RM-75 - NOKIA 7070 RH-116 - NOKIA 7100s RM-438 NOW UNLOCKS NOKIA BB5 PHONES WITHOUT OPENING PHONE ! Supported unlock in Nokia BB5 phones by FBUS cable: It unlocks 99% of BB5 phones BB5 (all known SW versions on 11/2008) except BB5+ Rap3Gv3 models: 3109c (RM-274), 3110c (RM-237), 3250 (RM-38), 3500c (RM-272), 3500cb (RM-273), 5200 (RM-174), 5200b (RM-181), 5300 (RM-146), 5300b (RM-147), 5500 (RM-86), 6085 (RM-198), 6086 (RM-188), 6086b (RM-260), 6125 (RM-178), 6126/6133