India's System of Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vividh Bharati Was Started on October 3, 1957 and Since November 1, 1967, Commercials Were Aired on This Channel

22 Mass Communication THE Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, through the mass communication media consisting of radio, television, films, press and print publications, advertising and traditional modes of communication such as dance and drama, plays an effective role in helping people to have access to free flow of information. The Ministry is involved in catering to the entertainment needs of various age groups and focusing attention of the people on issues of national integrity, environmental protection, health care and family welfare, eradication of illiteracy and issues relating to women, children, minority and other disadvantaged sections of the society. The Ministry is divided into four wings i.e., the Information Wing, the Broadcasting Wing, the Films Wing and the Integrated Finance Wing. The Ministry functions through its 21 media units/ attached and subordinate offices, autonomous bodies and PSUs. The Information Wing handles policy matters of the print and press media and publicity requirements of the Government. This Wing also looks after the general administration of the Ministry. The Broadcasting Wing handles matters relating to the electronic media and the regulation of the content of private TV channels as well as the programme matters of All India Radio and Doordarshan and operation of cable television and community radio, etc. Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC), which is a subordinate office, functions under the administrative control of this Division. The Film Wing handles matters relating to the film sector. It is involved in the production and distribution of documentary films, development and promotional activities relating to the film industry including training, organization of film festivals, import and export regulations, etc. -

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 the Thirteenth Finance Commission

1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Thirteenth Finance Commission has the unique opportunity to review and draw inferences from nearly six decades of federalism in public finance management of the nation. Based on such inferences, a much needed course correction can be initiated, reversing a trend that has been eroding the very concept of fiscal federalism. Government of Kerala would earnestly plead for such a focus in the work of this Commission. 1.2 Articles of the Constitution between 268 and 275 have designed a well-structured system whereby States get benefit from the Centre’s taxation power. The purpose is clear from the wording of Article 275 which is the final residual Article in this structure. Aid to the revenues of States is what the makers of Constitution had in mind. This really gives Finance Commission the authority to deal with the entire area where States’ revenues are applied – not just one part like non-plan revenue account expenditure. But Commissions chose to confine themselves to that area (with only one exception in recent times – Second report of the Ninth Finance Commission covering the period 1990- 95). Over the years, somehow it came to be accepted that Finance Commissions’ main task is to try and balance the non-plan revenue account of Stat es. 1.3 Whenever Commissions chose (or were asked) to look into other aspects, it was either for providing supplementary provisions for developmental expenditure (like special problem grants) or admonish States and guide them out of what was perceived to be their fiscal imprudence. The administration of such condition based grants and debt relief schemes was entrusted with Central Government Ministries. -

April 2020 Monthly Current Affairs Pdf English

winmeen.com 2020 APR 01 1. What is the deadline for completion of insolvency Manila–based Asian Development Bank (ADB) is to invest $100 million equivalent in the National resolution processes, as per the Insolvency and Investment and Infrastructure Fund – NIIF’s Funds. Bankruptcy code regulations? ADB joins the Government of India and Asian [A] 365 days B] 325 days Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as an investor in one of the instruments of NIIF of India. NIIF is an [C] 330 days [D] 331 investment platform for Indian and international As per the regulations of the Insolvency and investors where they are mandated to invest equity Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI), the overall deadline capital in domestic infrastructure. for completion of insolvency resolution processes is 330 days. 4. Which space company has received the contract of NASA to ferry cargo and supplies to the agency’s Recently, IBBI announced that against the backdrop of proposed lunar space station? the 21 day lockdown, IBBI has relaxed the timelines to be followed under the overall 330 day deadline. The [A] Blue Origin [B] SpaceX lockdown period will not be counted for the purpose of timelines under the IBBI regulations for Corporate [C] Astra Space [D] Exos Aerospace Insolvency Resolution Process. NASA has recently selected a new space capsule from 2. Which Indian newspaper that was being published in Elon Musk–owned SpaceX to ferry cargo and supplies to be used in its proposed lunar space station. the United States for 50 years has ceased its printed edition? The Lunar space station aims to build a permanent post on the moon and mount future missions to Mars. -

At the Crossroads

at the Crossroads SUSTAINING GROWTH AND REDUCING POVERTY ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionallyleft blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution at the Crossroads SUSTAINING GROWTH AND REDUCING POVERTY EDITED BY Tim Callen Patricia Reynolds Christopher Towe INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution 2001 International M netary Fund © o Production: IMF Graphics Section Cover design: Lai Oy Louie Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data India at the crossroads p. em. ISBN 1-55775-992-8 (alk. paper) 1. India--Economic policy--1980. 2. India--Economic conditions--1947- 3. Fiscal policy--India. 4. Sustainable development--India. HC435.2 .1484 2001 330.954--dc21 00-054132 Price: $2 7.00 Address orders ro: External Relations Department, Publication Services International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623-7430; Te lefax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http:l/www.imf.org ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution Contents Page Foreword . vii Acknowledgments . ix Overview 1. Christopher Towe 1 PART I. Preserving External Stability India and the Asia Crisis 2. Christopher To we . 11 3. Assessing India's External Position Tim Callen and Paul Cashin . 28 PART II. Fiscal Challenges 4. Tax Smoothing, Financial Repression, and Fiscal Deficits in India Paul Cashin, Nilss Olekalns, and Rama Sahay . 53 5. Fiscal Adjustment and Growth Prospects in India Patricia Reynolds . 75 PART III. Monetary and Financial Sector Policies Modeling and Forecasting Inflation in India 6. Callen . 105 Tim The Unit Trust of India and the Indian Mutual Fund 7. Industry Anna Ilyina . 122 ©International Monetary Fund. -

FUNDS RECOMMENDED by 12Th FINANCE COMMISSION and RELEASED by GOVT

FUNDS RECOMMENDED BY 12th FINANCE COMMISSION AND RELEASED BY GOVT. OF INDIA IN DIFFERENT YEARS (Rs. in Crores) Released by Recommendation Released by Recommendation Released by Recommendation Recommendation Released Recommendation Released by Recommendation Released by SL PURPOSES / SCHEMES GOI by of TFC GOI of TFC GOI of TFC of TFC by GOI of TFC GOI of TFC GOI (31.12.07) 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2005-10 1 Non-plan Revenue Deficit Grant. 488.04 488.04 0.00 0.00* 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 488.04 488.04 2 Central Share of Calamity Relief 226.16 226.16 232.68 232.68 239.53 239.53 246.73 324.50 254.27 0.00 1199.37 1022.87 3 Top up Grant for Education Sector 53.49 53.46 58.57 58.57 64.13 64.13 70.22 35.11 76.89 0.00 323.30 211.27 4 Top up Grant for Health Sector 31.22 31.22 34.81 34.81 38.81 19.41 43.28 21.64 48.25 0.00 196.37 107.08 5 Maintenance of Roads & Bridges. 0.00 0.00 368.77 368.77 368.77 368.77 368.77 368.77 368.77 0.00 1475.08 1106.31 6 Maintenance of Public Buildings. 0.00 0.00 97.28 97.28 97.28 97.28 97.29 48.65 97.29 0.00 389.14 243.21 7 Maintenance of Forests. 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 15.00 0.00 75.00 60.00 8 Heritage Conservation 0.00 0.00 12.50 12.50 12.50 12.50 12.50 9.37 12.50 0.00 50.00 34.37 9 State Specific Need (a+b) 0.00 0.00 42.50 40.50 42.50 3.75 42.50 46.44 42.50 0.00 170.00 131.44 a) Chilika Lake 0.00 0.00 7.50 7.50 7.50 3.75 7.50 11.44 7.50 0.00 30.00 26.44 b)Sewerage System for Bhubaneswar 0.00 0.00 35.00 33.00 35.00 0.00 35.00 35.00 35.00 0.00 140.00 105.00 10 Grants for local bodies. -

Pre Budget 2016-17

LIBRARY NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY 18/2- SATSANG VIHAR MARG, SPECIAL INSTITUTIONAL AREA, New Delhi-110067 NIPFP Library and Information Centre National Institute of Public Finance and Policy New Delhi Library and Information Centre of NIPFP gets roughly 13 newspapers among these 5 business newspapers are scanned and its clipping are selected & indexed in WINISIS software. Special care is taken to ensure that no important news event is left out of this selection. The arrangement of the clippings has been done with bibliography of authors-wise alphabetical index. This bulletin has the edited full text and it has been arranged serial number wise. Dr. Mohd. Asif Khan C O N T E N T S Bibliography of Newspaper Article 1-9 Bibliography Author Index 10 Full Text Author Index 10 Edited Full Text (Serial No. Wise) 11 Bibliography of Newspaper Articles ____________________________________________________ PRE BUDGET 1. Acharya,Shankar. Budget 2016 - Stick to basics: In a fragile global economic context, the Budget should err on the side of prudence. Business Standard, Feb 11, 2016, p.11. Global economy; Goods and Services Tax(GST); Employment and labour 2. Balaji,R.; Kumar,V. Sanjeev. Rationalisation of subsidies is key: Pricing policies, labour issues among other concerns of farm and fertiliser sectors. Financial Express, Feb 23, 2016, p.6. Agriculture; Fertiliser; Subsidy 3. Banerjee,Chandrajit. Budget 2016-17 should step up capital expenditure, implement tax reforms: The upcoming Budget should step up capital expenditure and implement tax reforms. Financial Express, Feb 2, 2016, p.9. Investment and savings; Infrastructure development; Rural development; Corporate tax 4. -

Thirteenth Finance Commission

ADVOCACY PAPER THIRTEENTH FINANCE COMMISSION (2010-2015) Memoranda by the Government of Bihar and Political Parties & Professional Organisations & Brief Recommendations for the State Centre for Economic Policy and Public Finance Asian Development Research Institute 0 Publisher Centre for Economic Policy and Public Finance Asian Development Research Institute BSIDC Colony, Off Boring-Patliputra Road Patna – 800 013 (BIHAR) Phone : 0612-2265649 Fax : 0612-2267102 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.adriindia.org Printer The Offsetters (India) Private Limited Chhajjubagh, Patna-800001 Disclaimer Usual disclaimers apply 1 CONTENTS Page No. PART A Brief Recommendations by the 4-8 Thirteenth Finance Commission PART B Bihar Government Memorandum 12-124 to the Thirteenth Finance Commission PART C Political Parties & Professional 130-207 Organisations’ Memorandum to the Thirteenth Finance Commission 2 PART A Brief Recommendations by the Thirteenth Finance Commission 3 Background In the existing federal financial arrangements of India, the financial resources are transferred from the centre to the states through a number of mechanisms. However, among them, it is the Finance Commission awards that are most important, both because of its size and the mandatory character of these recommendations. When the Thirteenth Finance Commission was formed in 2008, the Centre for Economic Policy and Public Finance (CEPPF) had already been established by the Government of Bihar in the Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI). As such, the CEPPF was entrusted with the responsibility of preparing the memorandum of the state government, to be presented to the Commission. For the three earlier Commissions, ADRI had presented a memorandum to the Tenth and Eleventh Finance Commission on its own behalf and, for the Twelfth Finance Commission, it had prepared and submitted a memorandum on behalf of all the political parties and professional organisations in the state. -

BUDGET TRACK How Many Miles Before We Get Fiscal Policy Space Right? a Periodical That Discusses the Budget and Policy Priorities of the Government

This document is for private circulation and not IN THIS ISSUE a priced publication. Copyright @ 2014 Centre for Budget and Significance of the Finance Commission Governance Accountability. The Diminution of the Finance Commission Reproduction of this publication for The 14th Finance Commission: With what porpoise? educational or other non-commercial purposes Paradigmatic Questions about the Mandate of the Fourteenth is authorized, without prior written Finance Commission permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Fourteenth Finance Commission in the context of emerging Centre–State Fiscal Relations ABOUT BUDGET TRACK How Many Miles Before We Get Fiscal Policy Space Right? A periodical that discusses the budget and policy priorities of the government. Reduced Fiscal Autonomy in States Erosion in Governance Capacity at the Sub-national Level CREDITS The Political Economy of Absorptive Capacity – Case of the Editorial Team: Health Sector Praveen Jha, Sona Mitra, Saumya Shrivastava, Volume 10, Track 1-2, October 2014 Subrat Das Panchayat Finances: Issues before the 14th Finance Commission CBGA Team: Suggestions for the Fourteenth Finance Commission on Amar Chanchal, Bhuwan C. Nailwal, Renewable Energy Gaurav Singh, Happy Pant, Strengthening Budget Transparency and Participation in India Harsh Singh Rawat, Jawed A. Khan, through the Pre-budget Process Jyotsna Goel, Kanika Kaul, Khwaja Mobeen Ur-Rehman, Manzoor Ali, Policy Asks for the 14th Finance Commission on Budget Nilachala Acharya, Pooja Rangaprasad, Transparency Priyanka -

Olitical Amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of olitical amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA fc I A Guide to the Microfiche Collection POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Associate Editor and Guide compiled by August A. Imholtz, Jr. A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaîion Data: Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by a printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55655-206-8 (microfiche) 1. Political parties-India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1I527 1989<MicRR> 324.254~dc20 89-70560 CIP International Standard Book Number: 1-55655-206-8 UPA An Imprint of Congressional Information Service 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD20814 © 1989 by University Publications of America Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. TABLE ©F COMTEmn Introduction v Note from the Publisher ix Reference Bibliography Part 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups India Congress Committee. (Including All India Congress Committee): 1-282 ... 1 Communist Party of India: 283-465 17 Communist Party of India, (Marxist), and Other Communist Parties: 466-530 ... 27 Praja Socialist Party: 531-593 31 Other Socialist Parties: -

Introduction

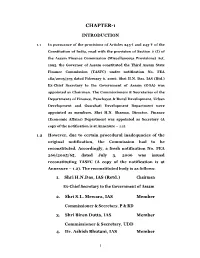

CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 In pursuance of the provisions of Articles 243-I and 243-Y of the Constitution of India, read with the provision of Section 2 (I) of the Assam Finance Commission (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1995, the Governor of Assam constituted the Third Assam State Finance Commission (TASFC) under notification No. FEA 182/2005/375 dated February 6, 2006. Shri H.N. Das, IAS (Rtd.) Ex-Chief Secretary to the Government of Assam (GOA) was appointed as Chairman. The Commissioners & Secretaries of the Departments of Finance, Panchayat & Rural Development, Urban Development and Guwahati Development Department were appointed as members. Shri H.N. Sharma, Director, Finance (Economic Affairs) Department was appointed as Secretary (A copy of the notification is at Annexure – 1.1). 1.2 However, due to certain procedural inadequacies of the original notification, the Commission had to be reconstituted. Accordingly, a fresh notification No. FEA 266/2005/65, dated July 3, 2006 was issued reconstituting TASFC (A copy of the notification is at Annexure – 1.2). The reconstituted body is as follows: 1. Shri H.N.Das, IAS (Retd.) Chairman Ex-Chief Secretary to the Government of Assam 2. Shri S.L. Mewara, IAS Member Commissioner & Secretary, P & RD 3. Shri Biren Dutta, IAS Member Commissioner & Secretary, UDD 4. Dr. Ashish Bhutani, IAS Member 1 Secretary, GDD 5. Shri K.V. Eapen, IAS Member- Secretary Commissioner & Secretary, Finance 1.3 Soon after reconstitution, Shri G.D. Tripathi, IAS, Joint Secretary, (presently Additional Secretary) Finance Department was appointed as Secretary, TASFC vide notification No. FEA 266/2005/80 dated July 25, 2006, in place of Shri H.N.Sharma who had been earlier appointed as Secretary (A copy of the notification is at Annexure -1.3). -

World Bank Document

Report No 19471-IN India Policies to Reduce Povertyand Public Disclosure Authorized Accelerate Sustainable Development January31, 2000 PovertyReduction and EconomicManagement Unit SouthAsia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the World Bank CURRENCY Rs/ US$ Currency Official Unified Market a Prior to June 1966 4.76 June 6, 1966 to mid-December 1971 7.50 Mid-December 1971 to end-June 1972 7.28 1971-72 7.44 1972-73 7.71 1973-74 7.79 1974-75 7.98 1975-76 8.65 1976-77 8.94 1977-78 8.56 1978-79 8.21 1979-80 8.08 1980-81 7.89 1981-82 8.93 1982-83 9.63 1983-84 10.31 1984-85 11.89 1985-86 12.24 1986-87 12.79 1987-88 12.97 1988-89 14.48 1989-90 16.66 1990-91 17.95 1991-92 24.52 1992-93 26.41 30.65 1993-94 31.36 1994-95 31.40 1995-96 33.46 1996-97 35.50 1997-98 37.16 1998-99 42.00 September 1999 43.54 October 1999 43.45 November 1999 43.39 Note: The Indian fiscal year runs from April 1 through March 31. Source: IMF, International Finance Statistics (IFS), line "rf"; Reserve Bank of India. a A dual exchange rate system was created in March 1992, with a free market for about 60 percent of foreign exchange transactions. The exchange rate was reunified at the beginning of March 1993 at the free market rate. Vice President Mieko Nishimizu Country Director Edwin Lim Sector Director Roberto Zagha Staff Members Sanjay Kathuria, James Hanson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS C urrency ....................................................................... -

13 Standing Committee on Finance

STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE 13 (1998-99) TWELFTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF FINANCE (DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS) THE CONSTITUTION (EIGHTY-FIFTH AMENDMENT) BILL, 1998 THIRTEENTH REPORT .1') I,~·· ~-i P LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT , ,~) (,) I "\ NEW DELHI 1,(', J (-~ • "i Id)rl/llri/,/999/I'/1IIIXIIII1l , 192(1 (Silkil) THIRTEENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE (1998-99) (TWELFTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF FINANCE (DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS) THE CONSTITUTION (EIGHTY-FIFTH AMENDMENT) BILL, 1998 Presen ted to Lok Sabha on 24 February, 1999 Laid il1 Rajya Sablm em 24 February, 1999 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI February, 1999/Phalguna, 1920 (Saka) CO.E. No. 13 Price: Rs. 12.00 © 1999 By LoK SABHA SECRIITARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Ninth Edition) and Printed by Jainco Art India, Delhi. CONTENTS PAGE C( lMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE .............................................................. (iii) INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. (V) REPORT ......................................................................................................... 1 ApPENDICES I. Minutes of the sitting of the Committee held on lR January, 1999 ................................................................. 7 II. Minutes of the sitting of Committee held on 17 February, 1999................................................. .............. 10 III. The Constitution (Eighty-Fifth Amendment) Bill, 1998 ....................................................................................