Interviewed by James O'connell 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ben Johnson Bibliography August 2019

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS 2019 Atkinson, William “Flagrant Exhibitionism: The Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition,” Cherwell, August 4 https://cherwell.org/2019.08.04/flagrant-exhibitionism-the-royal-academys-summer- exhibition/ 2018 “Insight - Finding Direction,” The British Museum Magazine Issue 92, Winter, p.5 2018 “Superstructures,” Icon, Architecture and Design Culture, April, pp.11, 76- 82 2018 “Reflections on Sacred Space by Ben Johnson,” Islamic Arts Magazine, January 7 http://islamicartsmagazine.com/magazine/view/reflections_on_sacred_space_by_ben_johnson/ 2017 Abdullah, Afkar. “Artists Unveil Authentic World of Contemporary Islamic Art,” Khaleej Times, Sharjah, December 14, p.6 2017 “Ben Johnson Southampton City Art Gallery,” Art Quarterly, Autumn, p.83 2017 "Architectural Reality Seen Through an Airbrush Painting," January 5 http://www.designstack.co/ 2016/01/architectural-reality-seen-through.html#.WG4lEIw8jZo. 2016 Finn, Pat. “More Detail Than the Eye Can See: The Superrealist Architectural Art of Ben Johnson,” Architizer, New York, April 25 http://architizer.com/blog/more-than- the-naked-eye-can- capture/ 2016 Rebane, Katariina. “The Artist Ben Johnson Doesn’t Sign His Work,” Eesti Päevaleht, Estonia, March 21, p.14 2016 “Hardly Distinguishable from a Photo: Hyper Realistic Paintings by Ben Johnson,” i-ref, Berlin, February 3 http://i-ref.de/iref-impuls/kaum-von-einem-foto-zu-unterscheiden-hyperrealistische-gemaelde-von- ben-johnson/ 2016 Spirou, Kiri. “The Superhuman Photorealism of Painter Ben Johnson,” Yatzer, January 11 https:// www.yatzer.com/ben-johnson 2016 Issue No.206 January 11 http://www.issueno206.com/ben-johnson-architectural-paintings/ 2016 “Pintura Arquitectónica,” Architectural Digest Mexico, January 8 http://www.admexico.mx/estilo-de-vida/editors-pick/articulos/pintura-arquitectura-diseno-color-arte- ben-johnson-cuadro/1704 2015 Szwarc, Eva. -

Museum of London Annual Report 2004-05

MUSEUM OF LONDON – ANNUAL REPORT 2004/05 London Inspiring MUSEUM OFLONDON-ANNUALREPORT2004/05 Contents Chairman’s Introduction 02 Directors Review 06 Corporate Mandate 14 Development 20 Commercial Performance 21 People Management 22 Valuing Equality and Diversity 22 Exhibitions 24 Access and Learning 34 Collaborations 38 Information and Communication Technologies 39 Collections 40 Facilities and Asset Management 44 Communications 45 Archaeology 48 Scholarship and Research 51 Publications 53 Finance 56 List of Governors 58 Committee Membership 59 Staff List 60 Harcourt Group Members 63 Donors and Supporters 64 MUSEUM OF LONDON – ANNUAL REPORT 2004/05 01 CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION On behalf of the Board of Governors I am pleased to report that the Museum of London has had another excellent year. On behalf of the Board of Governors I am pleased to report that the Museum of London has had another excellent year. My fellow Governors and I pay tribute to the leadership and support shown by Mr Rupert Hambro, Chairman of the Board of Governors from 1998 to 2005. There were many significant achievements during this period, in particular the refurbishment of galleries at London Wall, the first stage of the major redevelopment of the London Wall site, the opening of the Museum in Docklands and the establishment and opening of the London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre at Mortimer Wheeler House.The first stage of the London Wall site redevelopment included a new entrance, foyer and the Linbury gallery, substantially funded by the Linbury Trust.The Museum is grateful to Lord Sainsbury for his continuing support.There were also some spectacular acquisitions such as the Henry Nelson O’Neil’s paintings purchased with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Introduction National Art Collections Fund and the V&A Purchase Fund. -

Review of the Year 2010–2011

TH E April – March NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY April – March Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisition 8 Loans 10 Conservation 16 Framing 20 Exhibitions and Display 26 Education 42 Scientifi c Research 46 Research and Publications 50 Private Support of the Gallery 54 Financial Information 58 National Gallery Company Ltd 60 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 62 Figurative Architectural Decoration inside and outside the National Gallery 63 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2010 and March 2011, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review – The Trustees and Director of the National Gallery da Vinci), increased corporate membership and have spent much of the year just past in making sponsorship, income from donations or otherwise. plans to enable us to deal with the implications of The Government has made it clear that it cuts to our income Grant in Aid, the government wishes to encourage cultural institutions such as funding on which we, to a large extent, depend the National Gallery to place greater reliance on to provide our services to the public. private philanthropic support, and has this year At an early stage in the fi nancial year our income taken some fi rst steps to encourage such support, Grant in Aid was cut by %; and in the autumn we through relatively modest fi scal changes and other were told that we would, in the period to March initiatives. We hope that further incentives to , be faced with further cumulative cuts to our giving will follow, and we continue to ask for the income amounting to % in real terms. -

REALISMO REV 5.Pdf

Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Ministério da Cultura apresenta Banco do Brasil apresenta e patrocina SP_ 07 nov_18 14 jan_19 DF_ 04 fev 28 abr_19 RJ_ 14 mai 29 jul_19 50 Years of Realism _ From Photo-Realism to Virtual Reality Curadoria _ Tereza de Arruda Curator O Banco do Brasil apresenta a exposição 50 anos de Banco do Brasil presents the exhibition 50 Years of realismo – Do fotorrealismo à realidade virtual, que traça Realism – From Photo-Realism to Virtual Reality, offering um panorama da representação da realidade na arte visitors a panorama of reality as represented in contempo- contemporânea, nesse período. rary art during those five decades. Com obras desde a primeira geração de artistas With a selection that begins from early works of these dessas tendências, a mostra traz pintores do foto trends, the show features photo-realist and hyperrealist e hiper-realismo, pioneiros em proporcionar visibilidade painters who first made this art movement visible inter- para esse movimento artístico em um contexto inter- nationally, through to its expansion for experimentation in nacional, até sua expansão para a experimentação na virtual reality. realidade virtual. The artworks rendered in various supports, including Em suportes diversos, inclusive multimídia e tridimen- multimedia and tridimensional pieces, portray everyday sionais, representam a vida e objetos do cotidiano que life and its objects that in themselves pose a reflection— oferecem, em si, uma reflexão, não como um espelho da not as mirrors of reality, but as images of an individual’s realidade, mas da percepção do indivíduo em relação a ela. perception of it. -

20. Yüzyilda Sanatin Üretim, Tüketim Ve Eylem Alani Olarak Sokak

TC YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ SANAT VE TASARIM ANA SANAT DALI SANAT VE TASARIM YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ 20. YÜZYILDA SANATIN ÜRETİM, TÜKETİM VE EYLEM ALANI OLARAK SOKAK EREN GÜLBEY 09715004 TEZ DANIŞMANI PROF. RIFAT ŞAHİNER İSTANBUL 2012 ÖZ 20. YÜZYILDA SANATIN ÜRETİM, TÜKETİM VE EYLEM ALANI OLARAK SOKAK Eren Gülbey Eylül, 2012 Burjuva Devrimi’nin, Aydınlanma’nın ve Sanayileşme’nin tüm getiri ve götürüleri ile girilen 20. yüzyılda, kapitalist endüstrinin hızlı gelişimiyle ortaya çıkan tüm toplumsal, ekonomik, kültürel ve siyasi dönüşümler; hem sokağı hem sanatı hem de sokak ve sanat arasındaki ilişkiyi doğrudan etkilemiştir. Sokak, bu anlamda salt fiziksel bir mekan olmanın ötesinde toplumsal, kentsel ve gündelik hayat içindeki her türlü gelişmenin ve dinamiğin merkezinde olmuştur. Sanat ise tüm bu dönüşümlerin bir aracı ya da bir aktörü olarak, başka bir deyişle tüm bu gelişmelerin bizzat öznesi ya da nesnesi olarak, öyle ya da böyle yüzyıl boyunca etkin rol almıştır. Sanat alanı için 20. yüzyıl, geçmiş on dokuz yüzyılı ile her anlamda hesaplaştığı bir dönem olmuştur. Bu sorgulamaya sebep olan ise bahsi geçen dönüşümlerdir: Yani eski sistemlerin yerine gelen yeni sistemler, yeni üretim teknik ve biçimleri, yeni toplumsal ve kültürel yapılardır. Sanatçı, bu bağlamda gerek tüm bu yenilikleri yerinde keşfetmek üzere, gerek tüm bu yeni sistemle iktidar ve özgürlük mücadelesine girmek üzere, gerekse de tüm bu yeni sistem içinde yaşamını sürdürebilmek ve kendine bir rol, bir alan ya da bir kazanç sağlayabilmek üzere sokakta yer alabilmiştir. Bu çalışma, 20. yüzyıl boyunca sanatsal alanın ilgili tüm aktör ve araçlarının sokakta yer alma nedenlerini, süreçlerini ve sonuçlarını irdeleyerek ilgili kavram, yaklaşım, akım ve uygulamaları biraraya getirmeye çalışmaktadır. -

Cambridge Students Storm London

Essay p17 Arts p20 Magazine p14 Chinua Achebe on “Bring back the porn and V Good versus V Bad. his British-infl uenced pickled sharks.” A lament This week, Her Maj’s education on the Turner Prize presence on Facebook gets a thumbs up FRIDAY 12TH NOVEMBER 2010 THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1947 ISSUE NO 729 | VARSITY.CO.UK JU SHARDLOW/BILL PAUL ROUSSEAU Burglar caught Cambridge students by student storm London KIRSTY GRAY A 30-year-old male was arrested last on at the gathering crowds outside weekend in St John’s when a stu- NATASHA PESARAN the building, were quickly evacuated dent caught him trying to steal from Students from the University of once students began smashing win- unlocked rooms. Cambridge clashed with police at dows with sticks and rocks. The intruder had to be forcibly Conservative Party headquar- A line of approximately 20 police- restrained with the assistance of a ters in London, after a national men formed to defend the building, porter and another passing under- demonstration against university but were unable to prevent the graduate until police arrived. funding cuts and fees turned violent hundreds of students from surging The incident took place at 7.30am on Wednesday. forward into the foyer. on 30th October after the student Nearly 400 Cambridge students Protestors occupied the building recognised his trainers in the hands took part in the march through for around an hour, during which of an unfamiliar man passing him on central London, which saw tens of time crowds of students gathered the stairwell. -

An Investigation Into Hyperrealist Depictions of the Human Facial Surface

Michael David Roberts Imaging the Face: An Investigation into Hyperrealist Depictions of the Human Facial Surface PhD Thesis, Aberystwyth, 2013 I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: "Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed. And on the pedestal these words appear: `My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!' Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, The lone and level sands stretch far away". Ozymandias, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1819) Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed (candidate) Date STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

Clive Head Painting As Morphing

Clive Head Painting as Morphing The following notes were given as a lecture to an audience of artists, curators and academics at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art in February 2015. Space For me, painting has always been a preoccupation with creating space. For many years that was manifest as a realism which ran parallel to my physical engagement with the urban landscape. From my journey through real space I sought a fictive but believable equivalent. Often confused with photorealism, these paintings allowed an expanse of vision, looking around corners, and into different spaces. But the overall presentation was as a seamless totality and formal certainty. Clive Head/Nicolas Poussin at Dulwich Picture Gallery 2012 Such painting always exists on a knife edge. The ease of its acceptance results from the invention of the space, not the imitation of our world. Extend that invention in any one direction and that ease is replaced with a reality at odds with our own. My work has always been rooted in experimental drawing. Towards the end of 2012 I allowed the fragmentation of that drawing to characterise the resultant paintings more directly. It was a step away from an apparent ease towards a greater uncertainty, although works from earlier projects had proved to be disconcerting. My exhibition at the National Gallery, London in 2010 not only broke attendance records, but the gallery was permanently crowded as the audience were compelled by a palpable alternative to their experience of the real world. Something strange was going on. This wasn’t a reality familiar to our lens-based culture after-all. -

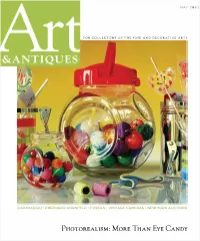

Photorealism: More Than Eye Candy Picture This

MAY 2010 FOR COLLECTORS OF THE FINE AND DECORATIVE ARTS CARAVAGGIO I EBERHARD KORNFELD I FOSSILS I VINTAGE CAMERAS I NEW YORK AUCTIONS PHOTOREALISM: MORE THAN EYE CANDY PICTURE THIS , - r PICTURE THIS BY SHEILA GIBSON STOODLEY A photorealist painting is always more than it appears to be. From the period mid-century cars of Robert Bechtle to the shimmering coats on the horses of Richard McLean, the cityscapes of Richard Estes, the multilayered shop windows of Tom Blackwell, the glistening glassware and cello phane of Roberto Bernardi and the sprawling landscapes of Raphaella Spence, these works invite wonder both for their high standard of craftsmanship and the individual visions of the artists. 68 ARl&ANTIOUES MAY 2010 With their intense realism and their PICTURE THIS meticulously painted, seemingly brushstroke-free surfaces, these works look very much like photographs-and they should, for they are based on photographs taken by the artists. Far from hiding their mechanical origins, these paintings showcase them, reveling in details that the unaided eye cannot see. The latest series from Arizona-based artist John Schieffer, for example, depicts splashes of liquid that can only be captured by high-speed film. But enjoying these artworks might be the least complicated thing about them. Let's start with what photorealist paintings are not: They are not works of trompe l'oeil, because while they are impressively realistic, they are not rendered to scale. And despite what their detractors claim, they are not mere copies of photographs. "I think people often have misconceptions about photorealism-'Why bother painting the scene when you just have a photograph of it?' But that's not what you get with photorealism at all," says Frank Bernarducci, partner and director of the Bernarducci Meisel gallery in New York. -

Still Lifes: the Extreme and the Trivial in Lisa Moore's Novel

Still Lifes: The Extreme and the Trivial in Lisa Moore’s Novel Alligator María Jesús Hernáez Lerena Universidad de La Rioja ABSTRACT: This paper studies the relationship between the composition methods of Lisa Moore’s novel Alligator (2005) and the visual effects of hyperrealist painting. The purpose is to find a common epistemology in certain narrative and visual discourses which may offer clues as to how to interpret some ethical issues such as a contemporary overexposure to photography in our daily life. This globalized visual overload, which is used by hyperrealist painters and by Lisa Moore to produce astonishingly renewing perceptions, is then examined in the context of Newfoundland’s society regarded as a repository of values which abruptly shift from old definitions of national/regional identity to the dilemmas of a post-industrial era, where the virtual worlds of technique can empty out people’s lives. Lisa Moore’s narrative proposal is apparently at odds with reactions of dismay of those theorists who claim that overexposure to images cancels out sympathy and activism (i.e., Susan Sontag, Jacques Rancière). However, Moore’s absolute engagement with reality as a visual phenomenon is complex; the novel offers creative alternatives for characters in the process of composing their biographies yet prevents identification with the social history of their community. M.J. Hernáez Lerena KEYWORDS: Hyperrealist painting, visual and narrative knowledge, Newfoundland. The philosopher apparently meets our expectations by spelling out what the “reverie” of the refined poets and the commitment of the contemporary artist have in common: the link between the solitude of the artwork and human community is a matter of transformed “sensation”. -

Photo Realism

Photo Realism As a full-fledged art movement Photorealism evolved from Pop Art, and as a counter to Abstract Expressionism as well as Minimalist art movements, in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States. Photorealists use a photograph, or several photographs, to gather the information to create their paintings, and it has been argued that the use of a camera and photographs is an acceptance of Modernism. Charles Thomas "Chuck" Close (born 1940) is an American painter, artist and photographer. He makes massive-scale photorealist portraits. Working from a gridded photograph, he builds his images by applying one careful stroke after another in multi-colours or grayscale. He works methodically, starting his loose but regular grid from the left hand corner of the canvas. His works are generally larger than life and highly focused. Close, Big Self-Portrait 1967-68 "One demonstration of the way photography became assimilated into the art world is the success of photorealist painting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is also called super- realism or hyper-realism and painters like Richard Estes, Denis Peterson, Audrey Flack, and Chuck Close often worked from photographic stills to create paintings that appeared to be photographs. The everyday nature of the subject matter of the paintings Close, Susan 1971 likewise worked to secure the painting as a realist object." G. Thompson: American Culture in the 1980's Richard Estes (born 1932) is regarded as one of the founders of the international photo-realist movement of the late 1960s. His paintings generally consist of reflective, clean, and inanimate city and geometric landscapes. -

Positioning Still Life by Means of Reference

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Thesis Title: Positioning still life by means of reference Creator: Chapman, J. Example citation: Chapman, J. (2012) Positioning still life by meanRs of reference. Doctoral thesis. The University of Northampton. A Version: Accepted version http://nectarC.northamptTon.ac.uk/8851/ NE Positioning Still Life by Means of Reference Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Northampton 2012 Jonathan Guy Chapman © [Jonathan Guy Chapman] [January 2012]. This thesis is copyright material and no quotation from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements I would like to thank The University of Northampton for supporting this PhD. I am also very grateful to my supervisors Dr. Vida Midgelow and Dr. Craig Staff for their excellent advice. I also wish to thank my parents and friends for their interest and encouragement. 2 Abstract This dissertation is presented as a framing document for a sixteen-year body of fine art practice, centred on the discipline of painting and the genre of still life, and disseminated by means of exhibition. Within it, I frame my practice as being referential in character, in respect of its conscious referencing of historic and contemporary art and art theory, and participation in the trans-historical referential constructs of a genre and realistic depiction. I describe my employment of reference as strategic in that it enables me to position my work in alignment with certain practice and theory and contest the nature of others. I argue also that this kind of referential positioning enables me to reconcile certain disparate artistic or theoretical positions.