The Making of the Gdańsk Metropolitan Region. Local Discourses of Identities, Powers, and Hopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6r33q03k Author Eaton, Nicole M. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 By Nicole M. Eaton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, chair Professor John Connelly Professor Victoria Bonnell Fall 2013 Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 © 2013 By Nicole M. Eaton 1 Abstract Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 by Nicole M. Eaton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair “Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948,” looks at the history of one city in both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia, follow- ing the transformation of Königsberg from an East Prussian city into a Nazi German city, its destruction in the war, and its postwar rebirth as the Soviet Russian city of Kaliningrad. The city is peculiar in the history of Europe as a double exclave, first separated from Germany by the Polish Corridor, later separated from the mainland of Soviet Russia. The dissertation analyzes the ways in which each regime tried to transform the city and its inhabitants, fo- cusing on Nazi and Soviet attempts to reconfigure urban space (the physical and symbolic landscape of the city, its public areas, markets, streets, and buildings); refashion the body (through work, leisure, nutrition, and healthcare); and reconstitute the mind (through vari- ous forms of education and propaganda). -

GDANSK EN.Pdf

Table of Contents 4 24 hours in Gdańsk 6 An alternative 24 hours in Gdańsk 9 The history of Gdańsk 11 Solidarity 13 Culture 15 Festivals and the most important cultural events 21 Amber 24 Gdańsk cuisine 26 Family Gdańsk 28 Shopping 30 Gdańsk by bike 32 The Art Route 35 The High Route 37 The Solidarity Route 40 The Seaside Route (cycling route) 42 The History Route 47 Young People’s Route (cycling route) 49 The Nature Route 24 hours in Gdańsk 900 Go sunbathing in Brzeźno There aren’t many cities in the world that can proudly boast such beautiful sandy beaches as Gdańsk. It’s worth coming here even if only for a while to bask in the sunlight and breathe in the precious iodine from the sea breeze. The beach is surrounded by many fish restaurants, with a long wooden pier stretching out into the sea. It is ideal for walking. 1200 Set your watch at the Lighthouse in Nowy Port The Time Sphere is lowered from the mast at the top of the historic brick lighthouse at 12:00, 14:00, 16:00 and 18:00 sharp. It used to serve ship masters to regulate their navigation instruments. Today it’s just a tourist attraction, but it’s well worth visiting; what is more, the open gallery at the top provides a splendid view of the mouth of the River Vistula and Westerplatte. 1300 Take a ride on the F5 water tram to Westerplatte and Wisłoujście Fortress Nowy Port and the environs of the old mouth of the Vistula at the Bay of Gdańsk have many attractions. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

1781 - 1941 a Walk in the Shadow of Our History by Alfred Opp, Vancouver, British Columbia Edited by Connie Dahlke, Walla Walla, Washington

1781 - 1941 A Walk in the Shadow of Our History By Alfred Opp, Vancouver, British Columbia Edited by Connie Dahlke, Walla Walla, Washington For centuries, Europe was a hornet's nest - one poke at it and everyone got stung. Our ancestors were in the thick of it. They were the ones who suffered through the constant upheavals that tore Europe apart. While the history books tell the broad story, they can't begin to tell the individual stories of all those who lived through those tough times. And often-times, the people at the local level had no clue as to the reasons for the turmoil nor how to get away from it. People in the 18th century were duped just as we were in 1940 when we were promised a place in the Fatherland to call home. My ancestor Konrad Link went with his parents from South Germany to East Prussia”Poland in 1781. Poland as a nation had been squeezed out of existence by Austria, Russia and Prussia. The area to which the Link family migrated was then considered part of their homeland - Germany. At that time, most of northern Germany was called Prussia. The river Weichsel “Vitsula” divided the newly enlarged region of Prussia into West Prussia and East Prussia. The Prussian Kaiser followed the plan of bringing new settlers into the territory to create a culture and society that would be more productive and successful. The plan worked well for some time. Then Napoleon began marching against his neighbors with the goal of controlling all of Europe. -

From a Far-Away Country of the Polish II Corps Heroes

Special edition Warsaw-Monte Cassino May 18, 2019 GLORY TO THE HEROES! ETERNAL BATTLEFIELD GLORY Dear Readers, n the glorious history of the Polish army, there were many battles where Iour soldiers showed exceptional heroism and sacrifice. The seizure of the Monte Cassino abbey has its special place in the hearts and memory of Poles. General Władysław Anders wrote in his order: “Long have we waited for this moment of retaliation and revenge on our eternal enemy. […] for this ruffianly attack of Germany on Poland, for partitioning Poland jointly with the Bolsheviks, […] for the misery and tragedy of our Fatherland, for our sufferings and exile.” The soldiers of the Polish II Corps did not waste this opportunity and seized the reinforced position in the abbey’s ruins, which had earlier been resisting the gunfire, bombing and attacks of the Allied forces. Polish determination and heroism broke the fierce defense line of the German forces. This victory was however paid very dearly for. On the hillside of Monte Cassino over 900 soldiers were killed, and almost 3,000 wounded. Still, the Monte Cassino success, although paid for with blood, paved the way to independent Poland. Saint John Paul II, when talking about the Battle of Monte Cassino, said about a live symbol of will to live, of sovereignty. These words perfectly define the attitude ...from a far-away country of the Polish II Corps heroes. They proved to be determined, patriotic, and The title might not be original, but it perfectly reflects the Polish-Italian full of will to fight. They were respected relations. -

For the SGGEE Convention July 29

For the SGGEE Convention July 29 - 31, 2016 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada 1 2 Background to the Geography It is the continent of Europe where many of our ancestors, particularly from 1840 onward originated. These ancestors boarded ships to make a perilous voyage to unknown lands far off across large oceans. Now, you may be wondering why one should know how the map of Europe evolved during the years 1773 to 2014. The first reason to study the manner in which maps changed is that many of our ancestors migrated from somewhere. Also, through time, the borders on the map of Europe including those containing the places where our ancestors once lived have experienced significant changes. In many cases, these changes as well as the history that led to them, may help to establish and even explain why our ancestors moved when they did. When we know these changes to the map, we are better able to determine what the sources of family information in that place of origin may be, where we may search for them, and even how far back we may reasonably expect to find them. A map of the travels of German people lets me illustrate why it has become necessary to acquaint yourself with the history and the changing borders of Eastern Europe. Genealogy in this large area becomes much more difficult without this knowledge. (See map at https://s3.amazonaws.com/ps-services-us-east-1- 914248642252/s3/research-wiki-elasticsearch-prod-s3bucket/images/thumb/a/a9/ Germans_in_Eastern_Europe5.png/645px-Germans_in_Eastern_Europe5.png) In my case, the Hamburg Passenger Lists gave me the name of the village of origin of my grandmother, her parents, and her siblings. -

FACTS and FIGURES Pasja I Kolor Naszej M³odoœci Nowe Wyzwania, Cuda Techniki Wielkie Idee, Ÿród³a M¹droœci Legenda Gdañskiej Politechniki

OK£ADKA 1 Hymn Politechniki Gdañskiej GDAÑSK UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY muzyka: Mi³osz Bembinow s³owa: Ryszard Kunce FACTS AND FIGURES Pasja i kolor naszej m³odoœci nowe wyzwania, cuda techniki wielkie idee, Ÿród³a m¹droœci legenda Gdañskiej Politechniki ref. Politechnika Gdañska otwarte g³owy i serca motto ¿yciem pisane: Historia m¹droœci¹ przysz³oœæ wyzwaniem! W naszym kampusie ducha rozœwietla blask Heweliusza i Fahrenheita oczy szeroko otwiera wszechœwiat g³êbi umys³om dodaje nauka Tutaj siê nasze marzenie spe³ni ka¿dego roku wielka to radoœæ duma i honor gdy absolwenci id¹ z odwag¹ kreowaæ przysz³oœæ 2 OK£ADKA 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Location of the University 3 Gdañsk University of Technology Campus 5 Patrons of the University 6 History of Gdañsk University of Technology 8 The mission of the University 10 The vision of the University 11 Education 12 International cooperation 18 Research 19 Certificates 20 Commercialization of research 22 Clusters 23 Centers for innovations 24 Cooperation with business and technology transfer 26 Programmes and projects 27 Joint ventures 28 With passion and imaginations 30 History is wisdom, future is challenge 32 FACTS AND FIGURES 2 LOCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY Gdañsk – is one of the largest business, economic, cultural and scientific centers. The capital of urban agglomeration of over one million citizens, and of the Pomeranian region inhabited by more than 2.2 million people. The most popular symbols of the city are: Neptune Fountain, the gothic St Mary's Basilica, called the crown of Gdañsk, and the medieval port crane on the Mot³awa River. -

I~ ~ Iii 1 Ml 11~

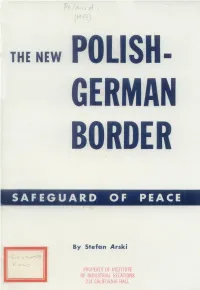

, / -(t POLIUSH@, - THE NEW GERMAN BODanER I~ ~ IIi 1 Ml 11~ By Stefan Arski PROPERTY OF INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS 214 CALIFORNIA HALL T HE NE W POLISH-GERMAN B O R D E R SAFEGUARD OF PEACE By Stefan Arski 1947 POLISH EMBASSY WASHINGTON, D. C. POLAND'S NEW BOUNDARIES a\ @ TEDEN ;AKlajped T5ONRHOLM C A a < nia , (Kbn i9sberq) Ko 0 N~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- K~~~towicealst Pr~~ue J~~'~2ir~~cou Shaded area: former German territories, east of the Oder and Neisse frontier, assigned to Poland at Potsdam by the three great Allied powers: the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain. The whole area comprising 39,000 square miles has already been settled by Poles. [ 2 ] C O N T E N T S Springboard of German Aggression Page 8 Foundation of Poland's Future - Page 21 Return to the West - Page 37 No Turning Back -Page 49 First Printing, February 1947 Second Printing, July 1947 PRINED IN THE U. S. A. al, :x ..Affiliated; FOREWORD A great war has been fought and won. So tremendous and far-reaching are its consequences that the final peace settlement even now is not in sight, though the representatives of the victorious powers have been hard at work for many months. A global war requires a global peace settlement. The task is so complex, however, that a newspaper reader finds it difficult to follow the long drawn-out and wearisome negotiations over a period of many months or even of years. Moreover, some of the issues may seem so unfamiliar, so remote from the immediate interests of the average American as hardly to be worth the attention and effort their comprehension requires. -

Wykaz Ulic Dla Sektora 1-6 Ulica Numery Sektor Dzielnica

Ulica Wykaz ulicNumery dla Sektora 1-6Sektor Dzielnica 11 Listopada 6 UJEŚCISKO-ŁOSTOWICE 3 Brygady Szczerbca 1 CHEŁM 3 Maja 2 ŚRÓDMIEŚCIE Achillesa 5 OSOWA Adama Asnyka 5 OLIWA Adama Mickiewicza 3 WRZESZCZ DOLNY Adolfa Dygasińskiego 4 ZASPA-ROZSTAJE Afrodyty 5 OSOWA Agrarna 5 MATARNIA Akacjowa 3 WRZESZCZ GÓRNY Aksamitna 2 ŚRÓDMIEŚCIE Akteona 5 OSOWA Akwenowa 1 WYSPA SOBIESZEWSKA Aldony 3 WRZESZCZ DOLNY Aleja Armii Krajowej 1 CHEŁM Aleja gen. Józefa Hallera 1-15 3 ANIOŁKI Aleja gen. Józefa Hallera 227 do końca 3 BRZEŹNO Aleja gen. Józefa Hallera 10-142; 17-209 3 WRZESZCZ DOLNY Aleja gen. Józefa Hallera 2-8 3 WRZESZCZ GÓRNY Aleja gen.Władysława Sikorskiego 1 CHEŁM Aleja Grunwaldzka 311-615; 476-612 5 OLIWA Aleja Grunwaldzka 203-244 3 STRZYŻA Aleja Grunwaldzka 1-201; 2-192 3 WRZESZCZ GÓRNY Aleja Jana Pawła II 3-29; 20-50 4 ZASPA-ROZSTAJE Aleja Jana Pawła II 2-6 4 ZASPA-MŁYNIEC Aleja Kazimierza Jagiellończyka 5 OSOWA Aleja Kazimierza Jagiellończyka 5 MATARNIA Aleja Kazimierza Jagiellończyka 5 KOKOSZKI Aleja Kazimierza Jagiellończyka 1 CHEŁM Aleja Legionów 3 WRZESZCZ DOLNY Aleja Rzeczypospolitej strona niezamieszkała 4 PRZYMORZE MAŁE Aleja Rzeczypospolitej 1-13 4 PRZYMORZE WIELKIE Aleja Rzeczypospolitej strona wsch. niezamieszkała 4 ZASPA-ROZSTAJE Aleja Rzeczypospolitej strona zach. niezamieszkała 4 ZASPA-MŁYNIEC Aleja Vaclava Havla 6 UJEŚCISKO-ŁOSTOWICE Aleja Wojska Polskiego 3 STRZYŻA Aleja Zwycięstwa 1-15; 33-59 3 ANIOŁKI Aleja Zwycięstwa 16/17 do 32 3 WRZESZCZ GÓRNY Aleksandra Dulin’a 6 UJEŚCISKO-ŁOSTOWICE Aleksandra Fredry 3 WRZESZCZ -

Welcoming Guide for International Students Powiślański University

Welcoming Guide for International Students Powiślański University Powiślański University Powiślański University was established in 1999 as a non-state university registered under number 166 in the Register of Non-Public Higher Education Institutions (formerly: the Register of Non-Public Higher Education Institutions and Associations of Non-Public Higher Education Institutions) kept by the Minister of Science and Higher Education. The Powiślański University is a non-profit organization. Its founder is the Society for Economic and Ecological Education in Kwidzyn, represented by people who are professionally connected with various forms of education and whose passion is the continuous improvement of methods and educational results. Reliable education of students is a priority for us, therefore we show particular care when selecting lecturers, taking into account their knowledge, qualifications, experience and skills. Institutional Erasmus + Program Coordinator: Paulina Osuch [email protected] / [email protected] Tel .: +48 795 431 942 Rector: prof. dr hab. Krystyna Strzała Vice-Rector for didactics and student affairs: dr Beata Pawłowska Vice-Rector for develomment and cooperation: dr Katarzyna Strzała-Osuch Chancellor Natalia Parus Chancellery tel. 55 261 31 39; [email protected] Supervisor: Aleksander Pietuszyński Deans office tel. 55 279 17 68; [email protected] Financial director: Małgorzata Szymańska Financial office: tel. 55 275 90 34; [email protected] More informations: https://psw.kwidzyn.edu.pl/ Insurance Before your arrival you are obliged to deliver Health Insurance. EU citizens and the residents of non-EU citizens Polish territory (i.e. Turkey and Ukraine) You are entitled to use free medical You should issue an insurance that will services on the basis of the European cover costs of medical help and Health Insurance Card (EHIC). -

Uchwała Nr XIII / 40 / 2020 Rady Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo Z Dnia 10.09.2020 R

Uchwała Nr XIII / 40 / 2020 Rady Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo z dnia 10.09.2020 r. w sprawie zaopiniowania projektów zgłoszonych do Budżetu Obywatelskiego 2021 Na podstawie §15 ust. 1 pkt. 15 Statutu Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo stanowiącego załącznik do Uchwały Nr LII/1173/14 Rady Miasta Gdańska z dnia 24.04.2014 r. w sprawie uchwalenia Statutu Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo (Dz. Urz. Woj. Pomorskiego z 29.05.2014 r., poz. 2003 z późn. zm.) uchwala się, co następuje: § 1. Opiniuje się wnioski zgłoszone do Budżetu Obywatelskiego 2021 w ramach projektów dzielnicowych Piecki-Migowo zgodnie z tabelą stanowiącą załącznik nr 1 do niniejszej uchwały. § 2. Opiniuje się wnioski zgłoszone do Budżetu Obywatelskiego 2021 w ramach projektów ogólnomiejskich zgodnie z tabelą stanowiącą załącznik nr 2 do niniejszej uchwały. § 3. Uchwała wchodzi w życie z dniem podjęcia. Przewodniczący Rady Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo Mateusz Zakrzewski Uzasadnienie: W związku z ustaleniami Panelu Obywatelskiego pt. „Jak wspierać aktywność obywatelską w Gdańsku?”, część „Jak usprawnić narzędzia partycypacji oraz jak wspierać aktywność obywatelską wśród osób dorosłych?”, rekomendacja nr 2 „Obowiązek opiniowania przez Radę Dzielnicy projektów zgłaszanych do budżetu obywatelskiego na etapie przed dopuszczeniem do głosowania i umieszczenie opinii na stronie budżetu obywatelskiego”, Rada Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo opiniuje projekty zgłoszone do Budżetu Obywatelskiego 2021. Wnioskodawca: Zarząd Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo Załącznik Nr 1 do Uchwały Nr XIII / 40 / 2020 Rady Dzielnicy Piecki-Migowo z dnia 10.09.2020 r. Zestawienie projektów dzielnicowych Piecki-Migowo zgłoszonych do Budżetu Obywatelskiego 2021 Numer Opinia Rady Dzielnicy Tytuł wniosku Piecki-Migowo PIE/0001 Koty - Pomóżmy im godnie żyć. pozytywna PIE/0002 Oświetlenie ul. prof. S. -

Hitler and the Treaty of Versailles: Wordlist

HITLER AND THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES: WORDLIST the Rhineland - a region along the Rhine River in western Germany. It includes noted vineyards and highly industrial sections north of Bonn and Cologne. demilitarized zone - in military terms, a demilitarized zone (DMZ) is an area, usually the frontier or boundary between two or more military powers (or alliances), where military activity is not permitted, usually by peace treaty, armistice, or other bilateral or multilateral agreement. Often the demilitarized zone lies upon a line of control and forms a de-facto international border. the League of Nations - the League of Nations (LON) was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference, and the precursor to the United Nations. At its greatest extent from 28 September 1934 to 23 February 1935, it had 58 members. The League's primary goals, as stated in its Covenant, included preventing war through collective security, disarmament, and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration. Other goals in this and related treaties included labour conditions, just treatment of native inhabitants, trafficking in persons and drugs, arms trade, global health, prisoners of war, and protection of minorities in Europe. the Sudetenland - Sudetenland (Czech and Slovak: Sudety, Polish: Kraj Sudetów) is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia associated with Bohemia. the Munich Agreement - the Munich Pact (Czech: Mnichovská dohoda;Slovak: Mníchovská dohoda; German: Münchner Abkommen; French: Accords de Munich; Italian:Accordi di Monaco) was an agreement permitting Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland.