Could Isidore's Chronicle Have Delighted Cicero?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural Science Underlying Big History

Review Article [Accepted for publication: The Scientific World Journal, v2014, 41 pages, article ID 384912; printed in June 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/384912] The Natural Science Underlying Big History Eric J. Chaisson Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA [email protected] Abstract Nature’s many varied complex systems—including galaxies, stars, planets, life, and society—are islands of order within the increasingly disordered Universe. All organized systems are subject to physical, biological or cultural evolution, which together comprise the grander interdisciplinary subject of cosmic evolution. A wealth of observational data supports the hypothesis that increasingly complex systems evolve unceasingly, uncaringly, and unpredictably from big bang to humankind. This is global history greatly extended, big history with a scientific basis, and natural history broadly portrayed across ~14 billion years of time. Human beings and our cultural inventions are not special, unique, or apart from Nature; rather, we are an integral part of a universal evolutionary process connecting all such complex systems throughout space and time. Such evolution writ large has significant potential to unify the natural sciences into a holistic understanding of who we are and whence we came. No new science (beyond frontier, non-equilibrium thermodynamics) is needed to describe cosmic evolution’s major milestones at a deep and empirical level. Quantitative models and experimental tests imply that a remarkable simplicity underlies the emergence and growth of complexity for a wide spectrum of known and diverse systems. Energy is a principal facilitator of the rising complexity of ordered systems within the expanding Universe; energy flows are as central to life and society as they are to stars and galaxies. -

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

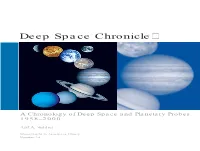

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

Prehistory of Clay Mineralogy – from Ancient Times to Agricola

Acta Geodyn. Geomater., Vol. 6, No. 1 (153), 87–100, 2009 PREHISTORY OF CLAY MINERALOGY – FROM ANCIENT TIMES TO AGRICOLA Willi PABST * and Renata KOŘÁNOVÁ Department of Glass and Ceramics, Institute of Chemical Technology, Prague (ICT Prague), Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] (Received November 2008, accepted February 2009) ABSTRACT The prehistory of clay mineralogy is highlighted from the beginnings in ancient Greece to the mineralogical works of Agricola, in particular his famous handbook of mineralogy, entitled De natura fossilium (1546). Starting with a few scattered hints in the works of Archaic and Classic Greek authors, including Aristotle, the first treatment of clays as a part of mineralogy is by Theophrastus. This basic tradition was further supplemented by Roman agricultural writers (Cato, Columella), Hellenistic authors (the geographer Strabo and the physicians Dioscorides and Galen), the Roman engineer- architect Vitruvius, and finally summarized in Pliny’s encyclopedia Naturalis historia, which has become the main source for later authors, including Agricola. It is shown to what extent Agricola’s work is just a great summary of this traditional knowledge and to what extent Agricola’s work must be considered as original. In particular, Agricola’s attempt to a rational, combinatorical classification of “earths” is recalled, and a plausible explanation is given for his effort to include additional information on Central European clay deposits and argillaceous raw material occurrences. However, it is shown that – in contrast to common belief – Agricola was not the first to include “earths” in a mineralogical system. This had been done almost one thousand years earlier by Isidore of Seville. -

'Law' in the Medieval Christianity As Understood from the Etymologies Of

International Journal of Arts and Commerce Vol. 4 No. 2 February, 2015 ‘Law’ in the Medieval Christianity as understood from the Etymologies of Isidore of Seville Samina Bashir1 Abstract The article is an attempt to explore the history behind and meaning of the term ‘law’ in medieval Christianity. Isidore of Seville’s ‘Etymologiae’ is an encyclopedia of etymology and has defined in detail ‘law’ and relevant terms. This provides a glimpse of ‘Medieval’ culture and society, legal concepts, different laws prevalent at that time, nature of crimes and punishments. Key words: etymologiae, bishop, medieval, culture, law, natural law, human law. The Medieval period of western European history is spread over ten centuries, followed the disintegration of Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th century and lasted till the Italian Renaissance in 15th century.2 Isidore is commonly known as Isidore of Seville. He was born in 560, in Cartagena, Spain. This was the time when his father Sevarianus brought his family to Seville from Cartagena, since Cartagena was invaded and controlled by Byzantine forces. After the death of his parents he was brought up and educated by his elder brother Leander whom he succeeded as bishop of Seville later in 600. He received his elementary education in the cathedral school of Seville. He mastered Latin, Hebrew and Greek.3 Reccared, the king, converted to Catholicism which established close ties between the Catholic Church and the Visigoth (Spanish) monarchy.4 It seems that Isidore had some political influence as well. He enjoyed the relationship of friendship with Sisebut (612-621) due to common intellectual interests.5 Braulio, his younger colleague, who later became bishop of the church of Saragossa in 636 and on whose request he wrote his famous ‘Etymologies’ and who after the death of Isidore compiled a list of his works wrote about his personality and he has introduced his Etymologies, “[Etymologiae] … a codex of enormous size, divided by him into topics, not books. -

The Plinian Races (Via Isidore of Seville) in Irish Mythology

Divine Deformity: The Plinian Races (via Isidore of Seville) in Irish Mythology Phillip A. Bernhardt-House Abstract: This article examines the characteristics of the Fomoiri in Irish mythological literature—particularly their being one-eyed, one-legged, and one- handed or one-armed—and rather than positing a proto-Indo-European or native Irish origin for these physical motifs, instead suggests that these characteristics may be derived from Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, which contains a catalogue of the ‘Plinian races’ of classical mythology and pseudo-ethnography within it. All of the Fomoiri’s characteristics can be compared to the physiological forms of the Giants, Sciopods, Cyclopes, and Blemmyae from the canonical list of Plinian races. Further omparison of Irish accounts of cynocephali (dog-headed humanoids) within texts like Lebor Gabála Érenn are also likely derived from Isidore. Irish pseudohistorical writings of the medieval period suggest that the isle of Ireland was invaded by successive waves of inhabitants, the first being a granddaughter of the biblical Noah called Cesair, who invaded Ireland shortly before the flood (Carey 1987), but died with the rest of her companions (apart from one, a long- lived shape-shifting survivor) in the flood itself. The next post-diluvial invasion was that of Partholón, and it was during this period when Partholón’s people were the principal inhabitants of Ireland that the first battle in Ireland occurred, which was against Cichol Grichenchos of the Fomoiri, a race described as ‘men with single arms and single legs’ in the first recension of the pseudohistorical textLebor Gabála Érenn, ‘The Book of the Taking of Ireland’ (The Book of Invasions, First Recension, 238 §38). -

Lhe STORY ()F-THE, NATIONS -~Be §Tor~ of Tbejsations

• lHE STORY ()F-THE, NATIONS -~be §tor~ of tbeJSations. _ THE- FRANKS THE STORY OF THE NATION S• • J. ROME. .By ARTKUR GILMAN, 30. THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE. M.A. lIy_ c. W. C. OMAN • •. THE JEWs. By Prof. J. K. 31. SICILY: Phc:elliclan, Greek HOSMER. and Roman. lIy tho late 3. GERMANY. By Rev. S. BAIliNG' Prof. E. A. f'I'REBMAN. GOULD, M.A. 32. THE TUSCAN REPUBLICS. 4. CARTHAGE. By Prof. A •. FRED BY_~F.LLA DUFP'Y. J. CHURCK. 33. POLAND. By w. R. MO •• ,LL, s· ALEXANDER'S EMPIRE. By M.A. Prof. J. P. MAKAFFV. 34- PARTHIA. By Prof. GEORGE 6. THE MOORS IN SPAIN. By RAWLINSON. STANLEY LANR.POO1' 35· AUSTRALIAN COMMON· 7. ANCIENT EGYPT. y Prof. WEALTH. By GREVILLB GEORt;P. RAWLINSON. TREGARTHEH. 8. HUNGARY. By Prof. ..MINlOS 36. SPAIN. By H. E. WAT,... VAMBRRY. 37. JAPAN. By DAYID AluKRAY, 9. THE SARACENS. By ARTKUR Ph.D. GILMAN, M.A. 38. SOUTH AFRIOA. By GF.ORGK 10. IRELAND. By the Hon. EMILY M. THKAL. • LAWLESS. 39. VENICE. By ALltTKEA W'EL. 11. CHALDBA. By Zt!NAiDE A. 40. THE CRUSADES. lIy T. A. RAGOZIN. ARCHER and C. L. K'NGs, 1" THE GOTHS. By HENRY BRAD· FORD. LEY. 41. VEDIa INDIA. By Z. A. R,,· 13. ABSYRIA. By ZgNAiDE A. RA. GOZIN. GOZIN. 42. WEST INDIES AND THE '14. TURKEY. By STANLEY LANE SPANISH MAIN. Ily JAME' POOLS. ){ODWAY. IS. HOLLAND. By Prof.' J. E. 43- BOHEMIA. By C. EDMUND THOROLD RoGERS. MAURICE. 16. MEDIEVAL FRANCE. By 44. THB BALKANS. By W. -

Can Literary Studies Survive? ENDGAME

THE CHRONICLE REVIEW CHRONICLE THE Can literary survive? studies Endgame THE CHRONICLE REVIEW ENDGAME CHRONICLE.COM THE CHRONICLE REVIEW Endgame The academic study of literature is no longer on the verge of field collapse. It’s in the midst of it. Preliminary data suggest that hiring is at an all-time low. Entire subfields (modernism, Victorian poetry) have essentially ceased to exist. In some years, top-tier departments are failing to place a single student in a tenure-track job. Aspirants to the field have almost no professorial prospects; practitioners, especially those who advise graduate students, must face the uneasy possibility that their professional function has evaporated. Befuddled and without purpose, they are, as one professor put it recently, like the Last Di- nosaur described in an Italo Calvino story: “The world had changed: I couldn’t recognize the mountain any more, or the rivers, or the trees.” At the Chronicle Review, members of the profession have been busy taking the measure of its demise – with pathos, with anger, with theory, and with love. We’ve supplemented this year’s collection with Chronicle news and advice reports on the state of hiring in endgame. Altogether, these essays and articles offer a comprehensive picture of an unfolding catastrophe. My University is Dying How the Jobs Crisis Has 4 By Sheila Liming 29 Transformed Faculty Hiring By Jonathan Kramnick Columbia Had Little Success 6 Placing English PhDs The Way We Hire Now By Emma Pettit 32 By Jonathan Kramnick Want to Know Where Enough With the Crisis Talk! PhDs in English Programs By Lisi Schoenbach 9 Get Jobs? 35 By Audrey Williams June The Humanities’ 38 Fear of Judgment Anatomy of a Polite Revolt By Michael Clune By Leonard Cassuto 13 Who Decides What’s Good Farting and Vomiting Through 42 and Bad in the Humanities?” 17 the New Campus Novel By Kevin Dettmar By Kristina Quynn and G. -

MERI-DIES ACCORDING to LATIN AUTHORS from CICERO to ANTHONY of PADUA: the VARIOUS USES of a COMMONPLACE ETYMOLOGY* Tim Denecker

ACTA CLASSICA LX (2017) 73-92 ISSN 0065-1141 MERI-DIES ACCORDING TO LATIN AUTHORS FROM CICERO TO ANTHONY OF PADUA: THE VARIOUS USES OF A COMMONPLACE ETYMOLOGY Tim Denecker Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), Leuven/Ghent ABSTRACT The etymology of meridies stands as a commonplace in the Latin literary tradition. The present article aims to expand on the evidence collected by Maltby in his 1991 A Lexicon of Ancient Latin Etymologies – primarily by extending its historical scope into the Middle Ages – and to interpret and contextualise the body of source material thus established. It is shown that in the relevant sources (chronologically ranging from Cicero [born 106 BC] to Anthony of Padua [died 1231]), the meri- component is mostly reduced to merus or to medius, but that combinations and minor alternative explanations frequently occur. It also becomes clear that the etymology of meridies is discussed and put to use in a broad variety of text types, and in very diverse historical and cultural contexts. Lastly, it is argued that the case of meridies is illustrative of the difference between ‘ancient’ and ‘modern’ concep- tions of etymology. Introduction The etymology of meridies, ‘midday, noon, south’, has commonplace status throughout the Latin literary tradition, including technical genres and exegetical works. In Maltby’s presentation of the relevant source material, three possible accounts of the word’s history can be discerned. According to what seems to be the oldest etymology, the components medius and dies (a noun which may have masculine or feminine gender) were contracted to medidies, which was subsequently altered by dissimilation – for the sake of euphony – into meridies. -

A Chronicle of the Reform: Catholic Music in the 20Th Century by Msgr

A Chronicle of the Reform: Catholic Music in the 20th Century By Msgr. Richard J. Schuler Citation: Cum Angelis Canere: Essays on Sacred Music and Pastoral Liturgy in Honour of Richard J. Schuler. Robert A. Skeris, ed., St. Paul MN: Catholic Church Music Associates, 1990, Appendix—6, pp. 349-419. Originally published in Sacred Music in seven parts. This study on the history of church music in the United States during the 20th century is an attempt to recount the events that led up to the present state of the art in our times. It covers the span from the motu proprio Tra le solicitudini, of Saint Pius X, through the encyclical Musicae sacra disciplina of Pope Pius XII and the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council and the documents that followed upon it. In knowing the course of development, musicians today may build on the accomplishments of the past and so fulfill the directives of the Church. Cum Angelis Canere, Appendix 6 Part 1: Tra le sollicitudini The motu proprio, Tra le sollicitudini, issued by Pope Pius X, November 22, 1903, shortly after he ascended the papal throne, marks the official beginning of the reform of the liturgy that has been so much a part of the life of the Church in this century. The liturgical reform began as a reform of church music. The motu proprio was a major document issued for the universal Church. Prior to that time there had been some regulations promulgated by the Holy Father for his Diocese of Rome, and these instructions were imitated in other dioceses by the local bishops. -

The Right of Magistrates

< 1 > The Right of Magistrates Concerning the Rights of Rulers Over Their Subjects and the Duty Of Subjects Towards Their Rulers. A brief and clear treatise particularly indispensable to either class in these troubled times. By Theodore Beza Translation by Henry-Louis Gonin, edited by Patrick S. Poole Notes from the critical French Edition translated by Patrick S. Poole To Kings and Princes the Counsel of David: Psalm 2: Serve the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling. Kiss the Son lest he be angry, and you perish in the way, for His wrath will soon be kindled. To the Subjects: I Peter 2:13: Be subjects to every ordinance of man for the Lord's sake. Contents: Question 1. Must Magistrates Always Be Obeyed As Unconditionally As God? Question 2. Is A Magistrate Held Responsible To Render Account Of All His Laws To His Subjects? And How Far Are They To Presume Such Laws To Be Just? Question 3. How Far Must Obedience Be Rendered Or Refused To Unjust Or Impious Commands? Question 4. How Can One Who Has Suffered Wrong At The Hands Of A Ruler Defend Himself Against Him? Chapter 5. Whether Manifest Tyrants Can Lawfully Be Checked By Armed Force. Question 6. What is the duty of subjects towards their superiors who have fallen into tyranny? Question 7. What must be done when the Orders or Estates cannot be summoned to impede or to check tyranny? Question 8. What may be done against unjust oppressors? Question 9. Whether subjects can contract with their rulers? Question 10. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Etymology (A Linguistic Window onto the History of Ideas) Version 1.0 June 2008 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: This short essay for a volume on the classical tradition aims to give a basic, lively account of the forms and development of etymological practice from antiquity to the present day. © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 Written in the fall of 2007 and spring of 2008, this 3,000-word entry will be published (I hope more or less in its present form) in The Classical Tradition, a reference work from Harvard University Press edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn Most, and Salvatore Settis. *** In the first decades of the seventh century CE, Isidore, Bishop of Seville, compiled a 20-book work in Latin called Etymologiae sive origines (“Etymologies or Origins”). Our knowledge of ancient and early medieval thought owes an enormous amount to this encyclopedia, a reflective catalogue of received wisdom, which the authors of the only complete translation into English introduce as “arguably the most influential book, after the Bible, in the learned world of the Latin West for nearly a thousand years” (Barney et al., 3). These days, of course, Isidore and his “Etymologies” are anything but household names—the translation dates only from 2006 and the heading of the wikipedia entry “Etymology” warns, “Not to be confused with Entomology, the scientific study of insects”—but the Vatican is reportedly considering naming Isidore Patron Saint of the Internet, which should make him and his greatest scholarly achievement known, if but dimly, to pretty much everyone.