Can Literary Studies Survive? ENDGAME

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Sociology 342-001: Criminology Summer II

Sociology 342-001: Criminology Summer II: July 8 – Aug. 7 2013 Online - 3 credits Instructor Office Hours Kate Gunby via email and gchat [email protected] or by appointment in Social Sciences 426 Course Description This course begins with a quick introduction to the multidisciplinary study of criminology, and how crime and criminal behavior are measured. Then the class will explore different theories of crime and criminality, starting with early schools of criminology and then covering structural, social process, critical, psychosocial, biosocial, and developmental theories. Then the class will focus on different types of crime, including violent crime, sex crimes, multiple murder and terrorism, property crime, public order crime, and white collar and organized crime. Finally, we will broaden our scope to explore victim experiences, mental health and incarceration, concepts of justice and incarceration trends, and the consequences of crime and incarceration. This course uses the acclaimed television series The Wire to explore the fundamentals of criminology. Students will develop their ability analyze, synthesize, apply, and evaluate the course material through written memos linking each reading to the content in a specific episode of The Wire. Students will further engage with the material and each other through online forum discussions. This class is guided by student goals, which are established from the beginning and reviewed throughout the term. Readings All of the course readings are on D2L. You do not need to buy any books. Almost all of the readings are excerpts from books or articles, so please download the readings from D2L so that you only read the portions that are required for the class. -

The Natural Science Underlying Big History

Review Article [Accepted for publication: The Scientific World Journal, v2014, 41 pages, article ID 384912; printed in June 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/384912] The Natural Science Underlying Big History Eric J. Chaisson Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA [email protected] Abstract Nature’s many varied complex systems—including galaxies, stars, planets, life, and society—are islands of order within the increasingly disordered Universe. All organized systems are subject to physical, biological or cultural evolution, which together comprise the grander interdisciplinary subject of cosmic evolution. A wealth of observational data supports the hypothesis that increasingly complex systems evolve unceasingly, uncaringly, and unpredictably from big bang to humankind. This is global history greatly extended, big history with a scientific basis, and natural history broadly portrayed across ~14 billion years of time. Human beings and our cultural inventions are not special, unique, or apart from Nature; rather, we are an integral part of a universal evolutionary process connecting all such complex systems throughout space and time. Such evolution writ large has significant potential to unify the natural sciences into a holistic understanding of who we are and whence we came. No new science (beyond frontier, non-equilibrium thermodynamics) is needed to describe cosmic evolution’s major milestones at a deep and empirical level. Quantitative models and experimental tests imply that a remarkable simplicity underlies the emergence and growth of complexity for a wide spectrum of known and diverse systems. Energy is a principal facilitator of the rising complexity of ordered systems within the expanding Universe; energy flows are as central to life and society as they are to stars and galaxies. -

“Express Yourself in New Ways” – Wait, Not Like That

“Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that A semiotic analysis of norm-breaking pictures on Instagram COURSE: Thesis in Media and Communication science II 15 credits PROGRAM: Media and Communication science AUTHORS: Andrea Bille Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen EXAMINER: Peter Berglez SEMESTER: FS2020 Title: “Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that Semester: FS2020 Authors: Andrea Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen Supervisor: Leon Barkho Abstract Instagram, as one of today’s largest social media platforms, plays a significant part in the maintaining and reproducing of existing stereotypes and role expectations for women. The purpose of the thesis is to study how Instagram interprets violations against its guidelines, and whether decisions to remove certain pictures from the platform are in line with terms of use, or part of human subjectivity. The noticeable pattern among the removed pictures is that they are often norm-breaking. The thesis discusses communication within Instagram to reveal how and why some pictures are removed while others are not, which limits women’s possibilities to express themselves in non-conventional settings. The study applies semiotics to analyse 12 pictures that were banned from the platform without directly violating its guidelines. Role theory and norms are used to supplement semiotics and shed light on the underlying societal structures of female disadvantage. Two major conclusions are presented: 1) Instagram has unclearly communicated its guidelines to women’s disadvantage, and 2) Instagram has therefore been subjective in the decisions to have the pictures removed from the platform, also to women’s disadvantage. Further, the discussion focuses on how Instagram handles issues related to (1) female sexuality, (2) women stereotyping, and (3) female self-representation. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

The JB's These Are the JB's Mp3, Flac

The J.B.'s These Are The J.B.'s mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: These Are The J.B.'s Country: US Released: 2015 Style: Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1439 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1960 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 880 Other Formats: APE VOX AC3 AA ASF MIDI VQF Tracklist Hide Credits These Are the JB's, Pts. 1 & 2 1 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 4:45 Frank Clifford Waddy*, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins 2 I’ll Ze 10:38 The Grunt, Pts. 1 & 2 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 3 3:29 Frank Clifford Waddy*, James Brown, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins Medley: When You Feel It Grunt If You Can 4 Written-By – Art Neville, Gene Redd*, George Porter Jr.*, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, 12:57 Joseph Modeliste, Kool & The Gang, Leo Nocentelli Companies, etc. Recorded At – King Studios Recorded At – Starday Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal Records Copyright (c) – Universal Records Manufactured By – Universal Music Enterprises Credits Bass – William "Bootsy" Collins* Congas – Johnny Griggs Drums – Clyde Stubblefield (tracks: 1, 4 (the latter probably)), Frank "Kash" Waddy* (tracks: 2, 3, 4) Engineer [Original Sessions] – Ron Lenhoff Engineer [Restoration], Remastered By – Dave Cooley Flute, Baritone Saxophone – St. Clair Pinckney* (tracks: 1) Guitar – Phelps "Catfish" Collins* Organ – James Brown (tracks: 2) Piano – Bobby Byrd (tracks: 3) Producer [Original Sessions] – James Brown Reissue Producer – Eothen Alapatt Tenor Saxophone – Robert McCullough* Trumpet – Clayton "Chicken" Gunnels*, Darryl "Hasaan" Jamison* Notes Originally scheduled for release in July 1971 as King SLP 1126. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

INDIVIDUATION and MYSTICAL UNION Jung and Eckhart

MARK JAMES INDIVIDUATION AND MYSTICAL UNION Jung and Eckhart Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) regularly quoted Meister Eckhart (ca.1260-1328) approvingly in his writings on Christianity.1 Jung thought that Christianity was suffering from arrested development and saw in Eckhart an ally. For Jung Chris- tianity and Christian symbols were in danger of being eclipsed because they no longer spoke to the human condition in the twentieth century. Churches that were supposed to care for the salvation of the soul were no longer able to help the individual achieve metanoia, the rebirth of the spirit. The Christian faith had lost its ability to connect people with an experience of the inner presence of God in their lives. Christianity, he believed, proclaimed an externalised God, a God aloof from people’s experience. While this externalisation of religion united individuals into a community of believers and even empowered them to provide a valuable social service to society, it lacked the capacity to transform the person’s inner life.2 It reinforces the idea that everything originates from without the person. A new process of self-nourishment was required which feeds a person’s interior life from internal not external resources. This means that Christianity could no longer remain a creed or a dogma of beliefs to which people adhered. In Eckhart, Jung saw a man after his own heart who sought to proclaim an immanent God and move away from the conception of God as ‘wholly other’.3 This comparative study seeks to contribute towards the ongoing discussion regarding the relationship between psychology and mysticism in spirituality stud- ies by engaging Jung and Eckhart in a dialogue with each other. -

Ebook Download Seinfeld Ultimate Episode Guide Ebook Free Download

SEINFELD ULTIMATE EPISODE GUIDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Bjorklund | 194 pages | 06 Dec 2013 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781494405953 | English | none Seinfeld Ultimate Episode Guide PDF Book Christmas episodes have also given birth to iconic storylines. Doch das vermeintliche Paradies hat auch seine Macken. Close Share options. The count includes both halves of three one-hour episodes, including the finale , and two retrospective episodes, each split into two parts: " The Highlights of ", covering the first episodes; and " The Clip Show ", also known as "The Chronicle", which aired before the series finale. Doch zuerst geht es um ihr eigenes Zuhause: Mobile 31 Quadratmeter werden auf mehrere Ebenen aufgeteilt. December is the most festive month of the year and plenty of TV shows — both new and old — have Christmas-themed episodes ready to rewatch. Spike Feresten. Finden sie ein Haus nach ihrer Wunschvorstellung - in bezahlbar? Main article: Seinfeld season 1. Cory gets a glimpse at what life would be like without Topanga and learns that maybe it's worth making a few compromises. Das Ehepaar hat in der Region ein erschwingliches Blockhaus mit Pelletheizung entdeckt. Doch noch fehlt ein Zuhause. Doch es wird immer schwieriger, geeignete Objekte auf dem Markt zu finden. Sound Mix: Mono. As they pass the time, the pair trade stories about their lives, which ultimately give clues to their current predicament. Was this review helpful to you? Jason Alexander. Favorite Seinfeld Episodes. Schimmel und ein kaputtes Dach sind nur der Anfang. Auch das Wohn-, Ess- und Badezimmer erstrahlen in neuem Glanz. Deshalb bauen die Do-it-yourself-Experten seinen Keller um. -

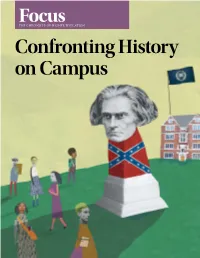

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Aims of Education Address

The Aims of Education Address By Andrew Abbott September 26, 2002 elcome to the University of the future will assume you’re good, no in the big nationwide studies, most of that who is a farmer and two who are doctors. Chicago.” matter what you do or how you do while effect comes through the connection be- So overall there is some slight evidence W Of the dozens of persons you are here. And of course we know, tween major and occupation. For the real of tracks towards particular occupations who will say that to you during this orien- pretty certainly, that having gotten in you variable driving worldly success—as all of from particular concentrations, but really tation week, I am the only one who will will graduate. Colleges compete in part by you know perfectly well—the one that the news is the reverse. The glass is not so keep on talking for another sixty minutes having high retention rates, and so it is in shapes income more than anything else, is much one-third full as two-thirds empty. after saying it. I imagine that you have the college’s very strong interest to make occupation. Occupation and major are Remember that only 40 percent of the heard few such orations before and that sure you graduate, whether you learn any- fairly strongly associated within the broad biology majors became doctors. And, more will you will hear few hereafter. A full- thing or not. categories of nationwide data. But within important, remember that our alumni’s length, formal talk on a set topic is a rather All of this tells me that nearly everyone the narrow range of occupation and achieve- experience shows very plainly that no path- nineteenth-century kind of thing to do. -

Science, Sovereignty, and the Sacred Text: Paleontological Resources and Native American Rights Allison M

Maryland Law Review Volume 55 | Issue 1 Article 5 Science, Sovereignty, and the Sacred Text: Paleontological Resources and Native American Rights Allison M. Dussias Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Allison M. Dussias, Science, Sovereignty, and the Sacred Text: Paleontological Resources and Native American Rights, 55 Md. L. Rev. 84 (1996) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol55/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCIENCE, SOVEREIGNTY, AND THE SACRED TEXT: PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES AND NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS ALLISON M. DussIAs* Land is the only thing in the world that amounts to anything... for 'tis the only thing in this world that lasts.... 'Tis the only thing worth working for, worth fightingfor-worth dying for.' -Gone with the Wind You have driven away our game and our means of livelihood out of the country, until now we have nothing left that is valuable except the hills that you ask us to give up.... The earth is full of minerals of all kinds, and on the earth the ground is covered with forests of heavy pine, and when we give these up to the Great Father we know that we give up the last thing that is valuable either to us or the white people.2 -Wanigi Ska (White Ghost) We believe that at the beginning of all things, when the earth was young, the thunderbirds were giants.