Fighting the Debt Crisis' Undertow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Sociology 342-001: Criminology Summer II

Sociology 342-001: Criminology Summer II: July 8 – Aug. 7 2013 Online - 3 credits Instructor Office Hours Kate Gunby via email and gchat [email protected] or by appointment in Social Sciences 426 Course Description This course begins with a quick introduction to the multidisciplinary study of criminology, and how crime and criminal behavior are measured. Then the class will explore different theories of crime and criminality, starting with early schools of criminology and then covering structural, social process, critical, psychosocial, biosocial, and developmental theories. Then the class will focus on different types of crime, including violent crime, sex crimes, multiple murder and terrorism, property crime, public order crime, and white collar and organized crime. Finally, we will broaden our scope to explore victim experiences, mental health and incarceration, concepts of justice and incarceration trends, and the consequences of crime and incarceration. This course uses the acclaimed television series The Wire to explore the fundamentals of criminology. Students will develop their ability analyze, synthesize, apply, and evaluate the course material through written memos linking each reading to the content in a specific episode of The Wire. Students will further engage with the material and each other through online forum discussions. This class is guided by student goals, which are established from the beginning and reviewed throughout the term. Readings All of the course readings are on D2L. You do not need to buy any books. Almost all of the readings are excerpts from books or articles, so please download the readings from D2L so that you only read the portions that are required for the class. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

Crime, Class, and Labour in David Simon's Baltimore

"From here to the rest of the world": Crime, class, and labour in David Simon's Baltimore. Sheamus Sweeney B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. August 2013 School of Communications Supervisors: Prof. Helena Sheehan and Dr. Pat Brereton I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: _55139426____ Date: _______________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Literature review and methodology 17 Chapter One: Stand around and watch: David Simon and the 42 "cop shop" narrative. Chapter Two: "Let the roughness show": From death on the 64 streets to a half-life on screen. Chapter Three: "Don't give the viewer the satisfaction": 86 Investigating the social order in Homicide. Chapter Four: Wasteland of the free: Images of labour in the 122 alternative economy. Chapter Five: The Wire: Introducing the other America. 157 Chapter Six: Baltimore Utopia? The limits of reform in the 186 war on labour and the war on drugs. Chapter Seven: There is no alternative: Unencumbered capitalism 216 and the war on drugs. -

Can Literary Studies Survive? ENDGAME

THE CHRONICLE REVIEW CHRONICLE THE Can literary survive? studies Endgame THE CHRONICLE REVIEW ENDGAME CHRONICLE.COM THE CHRONICLE REVIEW Endgame The academic study of literature is no longer on the verge of field collapse. It’s in the midst of it. Preliminary data suggest that hiring is at an all-time low. Entire subfields (modernism, Victorian poetry) have essentially ceased to exist. In some years, top-tier departments are failing to place a single student in a tenure-track job. Aspirants to the field have almost no professorial prospects; practitioners, especially those who advise graduate students, must face the uneasy possibility that their professional function has evaporated. Befuddled and without purpose, they are, as one professor put it recently, like the Last Di- nosaur described in an Italo Calvino story: “The world had changed: I couldn’t recognize the mountain any more, or the rivers, or the trees.” At the Chronicle Review, members of the profession have been busy taking the measure of its demise – with pathos, with anger, with theory, and with love. We’ve supplemented this year’s collection with Chronicle news and advice reports on the state of hiring in endgame. Altogether, these essays and articles offer a comprehensive picture of an unfolding catastrophe. My University is Dying How the Jobs Crisis Has 4 By Sheila Liming 29 Transformed Faculty Hiring By Jonathan Kramnick Columbia Had Little Success 6 Placing English PhDs The Way We Hire Now By Emma Pettit 32 By Jonathan Kramnick Want to Know Where Enough With the Crisis Talk! PhDs in English Programs By Lisi Schoenbach 9 Get Jobs? 35 By Audrey Williams June The Humanities’ 38 Fear of Judgment Anatomy of a Polite Revolt By Michael Clune By Leonard Cassuto 13 Who Decides What’s Good Farting and Vomiting Through 42 and Bad in the Humanities?” 17 the New Campus Novel By Kevin Dettmar By Kristina Quynn and G. -

I:\28531 Ind Law Rev 46-2\46Masthead.Wpd

THE WIRE AND ALTERNATIVE STORIES OF LAW AND INEQUALITY ROBERT C. POWER* INTRODUCTION The Wire was a dramatic television series that examined the connections among crime, law enforcement, government, and business in contemporary Baltimore, Maryland.1 It was among the most critically praised television series of all time2 and continues to garner substantial academic attention in the form of scholarly articles,3 academic conferences,4 and university courses.5 One aspect * Professor, Widener University School of Law. A.B., Brown University; J.D., Northwestern University Law School. Professor Power thanks Alexander Meiklejohn and John Dernbach for their comments on an earlier draft of this Article. He also thanks Lucas Csovelak, Andrea Nappi, Gabor Ovari, Ed Sonnenberg, and Brent Johnson for research assistance. 1. Substantial information about the series is available at HBO.COM, http://www.hbo.com/ the-wire/episodes#/the-wire/index.html [hereinafter Wire HBO site]. This site contains detailed summaries of each episode. Subsequent references to specific episodes in this Article refer to the season, followed by the number of the episode counting from the beginning of season one, and then the name of the episode. For example, the first episode of season four, which introduces the four boys who serve as protagonists in season four, is The Wire: Boys of Summer (HBO television broadcast Sept. 10, 2006) [hereinafter Episode 4-38, Boys of Summer]. Additional information is available at The Wire, IMDB.COM, http://www.imdb.com/ title/tt0306414/ (last visited Mar. 26, 2013) [hereinafter Wire IMDB site]. Several books contain essays and other commentaries about the series. -

Three Races' of North America," in Tocquevi/Le's Voyages

Allen, Barbara, 2014. "An Undertow ot Race Prejudice in the Current of Democratic Transformation: Tocqueville on the 'Three Races' of North America," in Tocquevi/le's Voyages .. Tocqueville's Voyages The Evolution of His Ideas and Their Journey Beyond His Time Edited and with an introduction by CHRISTINE DUNN HENDERSON ..amag, ] Liberty Fund Indianapolis i r: .2.. <:Jlr/ I ~f' .. Contents Note on the Contributors vii A magi books are published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and Introduction 1 responsible individuals. cHRISTINJ:<: DUNN HENDERSON ~~ PART I: TOCQUEVILLE AS VOYAGER The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as Hidden from View: Tocqueville's Secrets 1 a design element in all Liberty Fund books is the earliest-known 1 written appearance of the word "freedom" (amagi), or "liberty." 1mUARDO NOLLA It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. iu the 2 Tocqueville's Voyages: To and from America? 29 Sumerian city-state ofLagash. s. J• D. GREEN © 2014 by Liberty Fund, Inc. 3 Democratic Dangers, Democratic Remedies, and the Democratic All rights reserved Character 56 Printed in the United States of America JAMES T. SCHLEH'ER p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 l 4 Tocqueville's journey into America 79 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data JEREMY JENNINGS Tocqueville's voyages: the evolution of his ideas and their journey 5 Alexis de Tocqueville and the Two-Founding Thesis 111 beyond his time/edited and with an introduction by Christine JAMES W. -

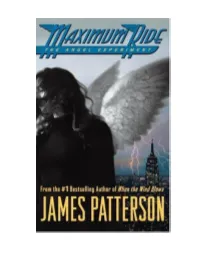

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT James Patterson WARNER BOOKS NEW YORK BOSTON Copyright © 2005 by Suejack, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Warner Vision and the Warner Vision logo are registered trademarks of Time Warner Book Group Inc. Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com First Mass Market Edition: May 2006 First published in hardcover by Little, Brown and Company in April 2005 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Cover design by Gail Doobinin Cover image of girl © Kamil Vojnar/Photonica, city © Roger Wood/Corbis Logo design by Jon Valk Produced in cooperation with Alloy Entertainment Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Maximum Ride : the angel experiment / by James Patterson. — 1st ed. p.cm. Summary: After the mutant Erasers abduct the youngest member of their group, the "bird kids," who are the result of genetic experimentation, take off in pursuit and find themselves struggling to understand their own origins and purpose. ISBN: 0-316-15556-X(HC) ISBN: 0-446-61779-2 (MM) [1. Genetic engineering — Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers — Fiction.] 1. Title. 10 9876543 2 1 Q-BF Printed in the United States of America For Jennifer Rudolph Walsh; Hadley, Griffin, and Wyatt Zangwill Gabrielle Charbonnet; Monina and Piera Varela Suzie and Jack MaryEllen and Andrew Carole, Brigid, and Meredith Fly, babies, fly! To the reader: The idea for Maximum Ride comes from earlier books of mine called When the Wind Blows and The Lake House, which also feature a character named Max who escapes from a quite despicable School. -

R17-00082-V05-N109-1895-07-14

P ~ .. N oname's" Lates t and Best Stories are Published in This Library. ~ COMPL ETE } FH.ANK TOUSEY. P£TRLISAER, 3! & 36 NORTH MOORE STREET, NEW YORK. { ) ' ltiCE } No.l09. { ' New York, June 14, 1895. ISSUED WEEKLY. 5 C J ~.N T S . Vol. V. Ente1·ed acc01•dino to the Act of Cono•·ess. in the yeur 1895, by FilA NT{ 7'0US/1;V, in the o(Tice of the Lib•·arian of Con(]ress, at Washinoton, D. C. or, Frank Reade, Jr.'s Sub marine Cruise in. the Lost in the Great Undertow; Gulf Stream. By '"'" NON.AME.'' If Frank could h ave m ade himself heard he would have shouted: "Hang on bravely! I am coming to help you." Forward he sprung and a ttacked the monster on the other hand. It was a lively sti·uggle which followed. Two of t he monster's tentacles were savered and its beak smashed before it yielded. • • 2 LOST IN THE GREAT UNDElfl'OW. The subscription price of the FRANK R E A:OE LIBR A RY by the year is $2.50 ; $1.25 per six mon ths, post paid. Address FRANK TOUSEY, PUBLISHER, 34 and 36 North Moore Street, New York. Box 2730. LOST IN THE GREAT UNDERTOW; OR, frtank Reade, Jrr.'s Subma~ine Grruise in the Gulf Strream. \ The Story of a, Wonderful Exploit. By 0 NONAME," Author of "The Chase of a Comet," "Around the Arctic Circle," etc., etc., etc. CB.tPTER J. Purinton's friend banded him a newspaper, and •the professor with varietl emotions read as follows: PROFESSOR PURINTON'S HOBBY, " Th.e Latest Triumph of our Great American Inventor, Frank OF course the rea~er is aware that the mighty ocean is not without Reade, Jr. -

Reflections on the Wire, Prosecutors, and Omar Little, 8 Ohio St

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2011 I Got the Shotgun: Reflections on The irW e, Prosecutors, and Omar Little Alafair Burke Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Alafair Burke, I Got the Shotgun: Reflections on The Wire, Prosecutors, and Omar Little, 8 Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 447 (2011) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/202 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Got the Shotgun: Reflections on The Wire, Prosecutors, and Omar Little Alafair S. Burke* I. INTRODUCTION The Wire, although it features police and prosecutors, is not a show that sets out to be about the law or the criminal justice system. Instead, the series creator, David Simon, views The Wire as a critique of the excesses of unencumbered capitalism: Thematically, it's about the very simple idea that, in this Postmodern world of ours, human beings-all of us-are worth less. Whether you're a corner boy in West Baltimore, or a cop who knows his beat, or an Eastern European brought here for sex, your life is worth less. It's the triumph of capitalism over human value. -

Race in High School Musical

"As true as television gets": The Wire and perceptions of realism A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture and Technology By Branden Buehler, B.A. Washington, DC April 22, 2010 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Literature Review 5 3 Form 18 4 Affect 34 5 Representation 49 6 Conclusion: The Text and the Extratextual 75 7 Bibliography 91 ii Introduction It is not rare to see a film or television show praised by critics for its “realism” or “authenticity.” It is rare, though, to see these types of accolades explained, much less critically examined. One television show that was particularly lauded for its realism was The Wire, a drama that ran on the premium cable channel HBO for five seasons between 2002 to 2008. As in most cases, the praise for its realism tended to be rather unspecific. In attempting to determine why audiences were so quick to hail the show for its authenticity, this thesis will argue that the perceptions of realism surrounding The Wire might be connected to properties of the text. More specifically, it will apply differing critiques of televisual realism to The Wire so as to assert that the show’s form, its affect and its treatment of representation are all possible reasons for the perceptions of realism. Furthermore, the thesis will be united by the argument that the show may have felt particularly realistic to its viewers because of deviations from the generic norms of the police drama -- generic deviation being a 'benchmark' for defining realism. -

Gender, Genre, and Seriality in the Wire and Weeds

DEALING WITH DRUGS: GENDER, GENRE, AND SERIALITY IN THE WIRE AND WEEDS By AMY LONG A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Amy Long 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like especially to thank my director, Trysh Travis, for her guidance, encouragement, and support throughout the writing process and my time at the University of Florida as a whole. Additionally, my committee members, Florence Babb and Joseph Spillane, deserve thanks for their participation in the project and particularly for, respectively, allowing me to work out some of the ideas presented here in here in her seminar fall 2007, Sex Love & Globalization, and providing me with useful reference materials and guidance. I would also like to thank LaMonda Horton Stallings for giving me the opportunity to develop substantial portions of my chapter on The Wire in her fall 2007 seminar, Theoretical Approaches to Black Popular Culture. In her spring 2008 seminar, History of Masculinities, Louise Newman also provided me with valuable theoretical resources, particularly with regard to the thesis’ first chapter. Mallory Szymanski, my Women’s Studies colleague, deserves acknowledgement for her role in making the last two years enjoyable and productive, particularly during the thesis writing process. I would also like to thank my parents for their support in all my endeavors. Lastly, my sisters, Beverly and Cassie Long, and friends who are too numerous to name (but know who they are) deserve special acknowledgment for giving me much needed diversions and generally putting up with me during this busy time. -

Wire Syllabus 09

AMST/FMMC 0277 - Urban American & Serial Television: Watching The Wire Professor Jason Mittell, Axinn 208, 443-3435 Office Hours: Mon 10-12 / Wed 10-12 / Thu 11-12 Class Meetings: T/Th 1:30 - 4:15 pm, Axinn 232 Mon 7:45 - 9:45 pm, Axinn 100 The Wire is dissent; it argues that our systems are no longer viable for the greater good of the most, that America is no longer operating as a utilitarian and democratic experiment. If you are not comfortable with that notion, you won't agree with some of the tonalities of the show. I would argue that people comfortable with the economic and political trends in the United States right now -- and thinking that the nation and its institutions are equipped to respond meaningfully to the problems depicted with some care and accuracy on The Wire -- well, perhaps they're playing with the tuning knobs when the back of the appliance is in flames. - David Simon Frequently hailed as a masterpiece of American television, The Wire shines a light on urban decay in contemporary America, creating a dramatic portrait of Baltimoreʼs police, drug trade, shipping docks, city hall, public schools, and newspapers over five serialized seasons. In this course, we will watch and discuss all of this remarkable—and remarkably entertaining—series and place it within the dual contexts of contemporary American society and the aesthetics of television. This is a time-intensive course with a focus on close viewing and discussion, and opportunities for critical analysis and research about the showʼs social contexts and aesthetic practices.