Cultural Rhetorics Pedagogy and Practices Under CUNY's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Sociology 342-001: Criminology Summer II

Sociology 342-001: Criminology Summer II: July 8 – Aug. 7 2013 Online - 3 credits Instructor Office Hours Kate Gunby via email and gchat [email protected] or by appointment in Social Sciences 426 Course Description This course begins with a quick introduction to the multidisciplinary study of criminology, and how crime and criminal behavior are measured. Then the class will explore different theories of crime and criminality, starting with early schools of criminology and then covering structural, social process, critical, psychosocial, biosocial, and developmental theories. Then the class will focus on different types of crime, including violent crime, sex crimes, multiple murder and terrorism, property crime, public order crime, and white collar and organized crime. Finally, we will broaden our scope to explore victim experiences, mental health and incarceration, concepts of justice and incarceration trends, and the consequences of crime and incarceration. This course uses the acclaimed television series The Wire to explore the fundamentals of criminology. Students will develop their ability analyze, synthesize, apply, and evaluate the course material through written memos linking each reading to the content in a specific episode of The Wire. Students will further engage with the material and each other through online forum discussions. This class is guided by student goals, which are established from the beginning and reviewed throughout the term. Readings All of the course readings are on D2L. You do not need to buy any books. Almost all of the readings are excerpts from books or articles, so please download the readings from D2L so that you only read the portions that are required for the class. -

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

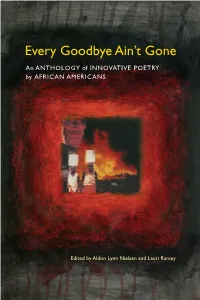

Every Goodbye Ain't Gone

Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An ANTHOLOGY of INNOVATIVE POETRY by AFRICAN AMERICANS Edited by Aldon Lynn Nielsen and Lauri Ramey Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETICS Series Editors Charles Bernstein Hank Lazer Series Advisory Board Maria Damon Rachel Blau DuPlessis Alan Golding Susan Howe Nathaniel Mackey Jerome McGann Harryette Mullen Aldon Nielsen Marjorie Perloff Joan Retallack Ron Silliman Lorenzo Thomas Jerr y Ward You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans Edited by ALDON LYNN NIELSEN and LAURI RAMEY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Copyright © 2006 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Typeface: Janson Text ∞ The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

This Bridge Called My Back Writings by Radical Women of Color Editors: Cherrie Moraga Gloria Anzaldua Foreword: Toni Cade Bambara

Winner0fThe 1986 BEFORECOLTJMBUS FOTJNDATION AMERICANBOOK THIS BRIDGE CALLED MY BACK WRITINGS BY RADICAL WOMEN OF COLOR EDITORS: _ CHERRIE MORAGA GLORIA ANZALDUA FOREWORD: TONI CADE BAMBARA KITCHEN TABLE: Women of Color Press a New York Copyright © 198 L 1983 by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. Published in the United States by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Post Office Box 908, Latham, New York 12110-0908. Originally published by Peresphone Press, Inc. Watertown, Massachusetts, 1981. Also by Cherrie Moraga Cuentos: Stories by Latinas, ed. with Alma Gomez and Mariana Romo-Carmona. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983. Loving in the War Years: Lo Que Nunca Paso Por Sus Labios. South End Press, 1983. Cover and text illustrations by Johnetta Tinker. Cover design by Maria von Brincken. Text design by Pat McGloin. Typeset in Garth Graphic by Serif & Sans, Inc., Boston, Mass. Second Edition Typeset by Susan L. Yung Second Edition, Sixth Printing. ISBN 0-913175-03-X, paper. ISBN 0-913175-18-8, cloth. This bridge called my back : writings by radical women of color / editors, Cherrie Moraga, Gloria Anzaldua ; foreword, Toni Cade Bambara. — 1st ed. — Watertown, Mass. : Persephone Press, cl981.[*] xxvi, 261 p. : ill. ; 22 cm. Bibliography: p. 251-261. ISBN 0-930436-10-5 (pbk.) : S9.95 1. Feminism—Literary collections. 2. Radicalism—Literary collections. 3. Minority women—United States—Literary collections. 4. American literature —Women authors. 5. American literature—Minority authors. 6. American literature—20th century. I. Moraga, Cherrie II. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Notes for the Downloaders

NOTES FOR THE DOWNLOADERS: This book is made of different sources. First, we got the scanned pages from fuckyeahradicalliterature.tumblr.com. Second, we cleaned them up and scanned the missing chapters (Entering the Lives of Others and El Mundo Zurdo). Also, we replaced the images for new better ones. Unfortunately, our copy of the book has La Prieta, from El Mundo Zurdo, in a bad quality, so we got it from scribd.com. Be aware it’s the same text but from another edition of the book, so it has other pagination. Enjoy and share it everywhere! Winner0fThe 1986 BEFORECOLTJMBUS FOTJNDATION AMERICANBOOK THIS BRIDGE CALLED MY BACK WRITINGS BY RADICAL WOMEN OF COLOR EDITORS: _ CHERRIE MORAGA GLORIA ANZALDUA FOREWORD: TONI CADE BAMBARA KITCHEN TABLE: Women of Color Press a New York Copyright © 198 L 1983 by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. Published in the United States by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Post Office Box 908, Latham, New York 12110-0908. Originally published by Peresphone Press, Inc. Watertown, Massachusetts, 1981. Also by Cherrie Moraga Cuentos: Stories by Latinas, ed. with Alma Gomez and Mariana Romo-Carmona. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983. Loving in the War Years: Lo Que Nunca Paso Por Sus Labios. South End Press, 1983. Cover and text illustrations by Johnetta Tinker. Cover design by Maria von Brincken. Text design by Pat McGloin. Typeset in Garth Graphic by Serif & Sans, Inc., Boston, Mass. Second Edition Typeset by Susan L. -

A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the De Grummond Collection Sarah J

SLIS Connecting Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection Sarah J. Heidelberg Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Heidelberg, Sarah J. (2013) "A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0201.09 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Collection Analysis of the African‐American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection By Sarah J. Heidelberg Master’s Research Project, November 2010 Performance poetry is part of the new black poetry. Readers: Dr. M.J. Norton This includes spoken word and slam. It has been said Dr. Teresa S. Welsh that the introduction of slam poetry to children can “salvage” an almost broken “relationship with poetry” (Boudreau, 2009, 1). This is because slam Introduction poetry makes a poets’ art more palatable for the Poetry is beneficial for both children and adults; senses and draws people to poetry (Jones, 2003, 17). however, many believe it offers more benefit to Even if the poetry that is spoken at these slams is children (Vardell, 2006, 36). The reading of poetry sometimes not as developed or polished as it would correlates with literacy attainment (Maynard, 2005; be hoped (Jones, 2003, 23). -

Beyond Inclusion: an In-Depth Analysis of Teaching of Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich

Yale College Education Studies Program Senior Capstone Projects Student Research Spring 2020 Beyond Inclusion: An In-Depth Analysis of Teaching of Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich Sarah Mele Yale College, New Haven Connecticut Abstract: This capstone will analyze interventions into university pedagogy based on the teaching practices of Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich. It begins with a historical introduction to the role of these four women in university activism in the late 1960s and early 1970s inside and outside the classroom. Analysis of the development of Black Studies and university pedagogy since this time reveals gaps in the fulfillment of the student-driven movement’s goal that are still extremely relevant to questions of institutional power and access today. Next, this paper provides concrete pedagogical and methodological strategies for present day university teaching grounded in the work of these four revolutionary women. This portion will pull from archival research of teaching materials, notes, and correspondence as well as subsequent scholarship on pedagogy. Suggested Citation: Mele, S. (2020). Beyond Inclusion: An In-Depth Analysis of Teaching of Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich (Unpublished Education Studies capstone). Yale University, New Haven, CT. This capstone is a work of Yale student research. The arguments and research in the project are those of the individual student. They are not endorsed by Yale, nor are they official university positions or statements. Beyond Inclusion: An In-Depth Analysis of Teaching of Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich Sarah Mele 4/18/20 EDST 400 1 Abstract This capstone will analyze interventions into university pedagogy based on the teaching practices of Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich. -

Global Feminism, Comparatism, and the Master's Tools

15 Compared to What? Global Feminism, Comparatism, and the Master's Tools SUSAN SNIADER LANSER And rain is the very thing that you, just now, do not want, for you are thinking of the hard and cold and dark and long days you spent working in North America (or, worse, Europe), earning some money so that you could stay in this place (Antigua) where the sun always shines and where the climate is deliciously hot and dry ...and since you are on your holiday, since you are a tourist, the thought of what it might be like for someone who had to live day in, day out in a place that suffers constantly from drought ...must never cross your mind. And you leave, and from afar you watch as we do to ourselves the very things you used to do to us. And you might feel that there was more to you than that, you might feel that you had understood the meaning of the Age of Enlightenment (though, as far as I can see, it has done you very little good); you loved knowl edge, and wherever you went you made sure to build a school, a library (yes, and in both of these places you distorted or erased my history and glorified your own). As for what we were like before we met you, I no longer care. No periods of time over which my ancestors held sway, no doc umentation of complex civilisations, is any comfort to me. Even if I really came from people who were living like monkeys in trees, it was better to be that than what happened to me, what I became after I met you. -

Special Issue 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571

BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science An Online, Peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal Vol: 2 Special Issue: 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 UGC approved Journal (J. No. 44274) CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in | www.bodhijournals.com BODHI BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science (ISSN: 2456-5571) is online, peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal, which is powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services, (CRRPS) India. It is committed to bring together academicians, research scholars and students from all over the world who work professionally to upgrade status of academic career and society by their ideas and aims to promote interdisciplinary studies in the fields of humanities, arts and science. The journal welcomes publications of quality papers on research in humanities, arts, science. agriculture, anthropology, education, geography, advertising, botany, business studies, chemistry, commerce, computer science, communication studies, criminology, cross cultural studies, demography, development studies, geography, library science, methodology, management studies, earth sciences, economics, bioscience, entrepreneurship, fisheries, history, information science & technology, law, life sciences, logistics and performing arts (music, theatre & dance), religious studies, visual arts, women studies, physics, fine art, microbiology, physical education, public administration, philosophy, political sciences, psychology, population studies, social science, sociology, social welfare, linguistics, literature and so on. Research should be at the core and must be instrumental in generating a major interface with the academic world. It must provide a new theoretical frame work that enable reassessment and refinement of current practices and thinking. This may result in a fundamental discovery and an extension of the knowledge acquired. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

PART 1 Rresistanceesistance to Sslaverylavery

PART 1 RResistanceesistance to SlaverySlavery A Ride for Liberty, or The Fugitive Slaves, 1862. J. Eastman Johnson. 55.9 x 66.7 cm. Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York. “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.” —Frederick Douglass Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave 329 J. Eastman Johnson/The Bridgeman Art Library 0329 U3P1-845481.indd 329 4/6/06 9:00:01 PM BEFORE YOU READ Three Spirituals WHO WROTE THE SPIRITUALS? he spirituals featured here came out of the oral tradition of African Americans Tenslaved in the South before the outbreak of the Civil War. These “sorrow songs,” as they were called, were created by anonymous artists and transmitted by word of mouth. As a result, several versions of the same spiritual may exist. According Some spirituals served as encoded messages by to the Library of Congress, more than six thousand which enslaved field workers, forbidden to speak spirituals have been documented, though some are to each other, could communicate practical infor- not known in their entirety. mation about escape plans. Some typical code African American spirituals combined the tunes words included Egypt, referring to the South or the and texts of Christian hymns with the rhythms, state of bondage, and the promised land or heaven, finger-snapping, clapping, and stamping of tradi- referring to the North or freedom. To communi- tional African music. The spirituals allowed cate a message of hope, spirituals frequently enslaved Africans to retain some of the culture of recounted Bible stories about people liberated from their homelands and forge a new culture while fac- oppression through divine intervention.