“Express Yourself in New Ways” – Wait, Not Like That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lagniappe Spring 2015

Junior League of New Orleans LagniappeLagniappeSpring 2015 The 10th Annual Kitchen Tour JLNO and featuring the Idea Village House Beautiful Collaborate on Kitchen of the Big Ideas Year SUSTAINER OF THE YEAR: PEGGY LECORGNE LABORDE When you need to find a doctor in new orleans, touro makes it easy. We can connect you to hundreds of experienced physicians, from primary care providers to OB-GYNs Find a doctor to specialists across the spectrum. close to you. Offices are conveniently located throughout the New Orleans area. Visit touro.com/findadoc, or talk to us at (504) 897-7777. touro.com/Findadoc Boy and Girls Pre-K – 12 Ages 1 – 4 All-Girls’ Education 1538 Philip Street 2343 Prytania Street (504) 523-9911 (504) 561-1224 LittleGate.com McGeheeSchool.com Little Gate is open to all qualified girls and boys regardless of race, religion, national or ethnic origin. Louise S. McGehee School is open to all qualified girls regardless of race, religion, national or ethnic origin. www.jlno.org 1 2014-2015 The Hainkel Home 612 Henry Clay Avenue Lagniappe Staff New Orleans, LA 70118 Editor Kelly Walsh Phone : 504-896-5900 Fax: 504-896-5984 Assistant Editor “They have an exemplary quality assurance program… I suspect the Hainkel Home Amanda Wingfield Goldman is one of the best nursing homes in the state of Louisiana… This is a home that the Writers city of New Orleans needs, desperately needs.” – Dr. Brobson Lutz Mary Audiffred Rebecca Bartlett TIffanie Brown Ann Gray Conger New Parkside Red Unit Heather Guidry Heather Hilliard Services Include: Jacqueline Stump • Private and Semi- Private Rooms Lea Witkowski-Purl • Skilled Services including Photographers Speech, Physical, Occupational Denyse Boudreaux Therapy Jennifer Capitelli Kathleen Dennis • Licensed Practical and Registered Melissa Guidry Nurses on duty 24 hours a day. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

Training Manual

TRAINING MANUAL For sensitizing intermediaries on sexual rights of young people with learning disabilities Abstract This manual has been developed for organizations who wish to educate and sensitize staff, teachers and carers about the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of young people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Although it mainly focuses on intermediaries that are staff in an institution for young people with learning disabilities, it may well also be appropriate as a programme for the parents and family of young people with learning disabilities This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Daphne III Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of IPPF European Network and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. 2 Manual for Sensitizing Intermediaries On sexual rights of young people with learning disabilities About the manual Who is it for? This manual has been developed for organizations who wish to educate and sensitize staff, teachers and carers about the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of young people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Although it mainly focuses on intermediaries that are staff in an institution for young people with learning disabilities, it may well also be appropriate as a programme for the parents and family of young people with learning disabilities. What is its purpose? The manual outlines the main themes to be covered in a training programme for intermediaries of young people with learning disabilities, and suggests exercises to discuss these themes. -

Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from Rupaul's Drag Race

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 3 Feminist Comforts and Considerations amidst a Global Pandemic: New Writings in Feminist and Women’s Studies—Winning and Article 3 Short-listed Entries from the 2020 Feminist Studies Association’s (FSA) Annual Student Essay Competition May 2020 Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race Phoebe Chetwynd Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chetwynd, Phoebe (2020). Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(3), 22-35. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss3/3 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race By Phoebe Chetwynd1 Abstract The popularity of the reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race is often framed as evidence of Western societies’ increasing tolerance towards queer identities. This paper instead considers the ideological cost of this mainstream success, arguing that the show does not successfully challenge dominant heteronormative values. In light of Rosalind Gill’s work on postfeminism, it will be argued that the show’s format calls upon contestants (and viewers) to conform to a postfeminist ideal that valorises normative femininity and reaffirms the gender binary. -

Scissoring Dick Booty Call Sad Handjob

DIRTY BINGO BOOTY SAD SCISSORING DICK BOOBS CALL HANDJOB DOGGIE DEEPTHROAT SEX JIZZ WANKER STYLE FREE STIFFY TEASE SEXY ANAL G-SPOT STRAP QUEEF PISS LICK ORGASM ON GLORY BLOW MILF BONDAGE STROKE HOLE JOB This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 47 events. 69, ANAL, ASS, BACK DOOR, BITCH, BLOW JOB, BONDAGE, BOOBS, BOOTY CALL, CAMEL TOE, CLIMAX, COCK, CUM, CUNNILINGUS, DEEPTHROAT, DICK, DILDO, DOGGIE STYLE, FINGERING, GLORY HOLE, HORNY, HOT, JIZZ, LICK, LUBE, MILF, NIPPLES, ORGASM, PISS, PRICK, QUEEF, SAD HANDJOB, SCISSORING, SEX, SEXY, SHAFT, SPANK, STIFFY, STRAP ON, STROKE, TEASE, THREESOME, TICKLE, TWAT, VA-J-J, VIBRATOR, WANKER. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved DIRTY BINGO PRICK SPANK JIZZ THREESOME TWAT BOOTY BACK SEX SEXY VIBRATOR CALL DOOR FREE CAMEL COCK CLIMAX HOT G-SPOT TOE STRAP STROKE BOOBS ANAL 69 ON CUM STIFFY ASS PISS MILF This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 47 events. 69, ANAL, ASS, BACK DOOR, BITCH, BLOW JOB, BONDAGE, BOOBS, BOOTY CALL, CAMEL TOE, CLIMAX, COCK, CUM, CUNNILINGUS, DEEPTHROAT, DICK, DILDO, DOGGIE STYLE, FINGERING, GLORY HOLE, HORNY, HOT, JIZZ, LICK, LUBE, MILF, NIPPLES, ORGASM, PISS, PRICK, QUEEF, SAD HANDJOB, SCISSORING, SEX, SEXY, SHAFT, SPANK, STIFFY, STRAP ON, STROKE, TEASE, THREESOME, TICKLE, TWAT, VA-J-J, VIBRATOR, WANKER. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved. -

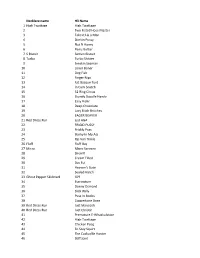

Who Cuming List As 7 18 13.Xlsx

Necklace name H3 Name 1 High Twattage High Twattage 2 Two Fisted Hose Master 3 Take it Lik a Man 4 Stinkin Pussy 5 Nut N Honey 6 Penis Butter 7 S Biscuit Semen Biscuit 8 Turbo Turbo Shitter 9 Smokin Seaman 10 Loner Boner 11 Dog Fish 12 Finger Nips 13 Fat Basque Turd 14 In Cum Snatch 15 32 Ring Circus 16 Skandy Doodle Handy 17 Easy Rider 18 Deep Chocolate 19 Lacy Bitch Britches 20 EAGER BEAVER 21 Red Dress Run just AGA 22 FRIGID PUSSY 23 Prickly Puss 24 Stinky In My Ass 25 Rip Van Tinkle 26 Fluff Fluff Boy 27 Micro Micro Screwry 28 Sherriff 29 Cream Filled 30 Das Fut 31 Heaven's Gate 32 Sealed Hatch 33 Ghost Pepper Skidmark GPS 34 Escrowtum 35 Donny Osmond 36 Slick Willy 37 Puss In Boobs 38 Coppertone Bone 39 Red Dress Run Just Maneesh 40 Red Dress Run Just Christin 41 Premature E-Whackulation 42 High Twattage 43 Chicken Poop 44 Sit Stay Squirt 45 The Cockodile Hunter 46 Stiff Joint 47 Deep Throat 48 Chicken Cox 49 Whaleboner 50 Brown vs The Board of Fornication 51 Beef Eater 52 Dick Shavin's Vagina Juice 53 Cheeky Cheek-a-Boo 54 Ganjaman 55 Easy Going 56 BMW BMW 57 All Sticky All Sticky 58 Close 2 Uranus 59 I Could Have Had a Blowjob 60 Shady Curtains 61 Jacuzzi Douche Me 62 Furry Mason 63 Village Tool 64 Stiff On Trail 65 The Little Spermaid 66 BORT BORT 67 Nookie Monster 68 Red Dress Run just thomas 69 Red Dress Run just jeannine 70 Redwood Floors 71 Turd Bird 72 Go Go Dancer 73 Howdy Howdy Do Me 74 Blinded by Boobs 75 Red Dress Run Just Angela 76 Mas Penis 77 Rectum Rider 78 Surf N Turf 79 Air Whores One 80 SMD SMD 81 Flip Flop Flip -

Social Norms, Shame, and Regulation in an Internet Age Kate Klonick

Maryland Law Review Volume 75 | Issue 4 Article 4 Re-Shaming the Debate: Social Norms, Shame, and Regulation in an Internet Age Kate Klonick Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Internet Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation 75 Md. L. Rev. 1029 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-SHAMING THE DEBATE: SOCIAL NORMS, SHAME, AND REGULATION IN AN INTERNET AGE * KATE KLONICK Advances in technological communication have dramatically changed the ways in which social norm enforcement is used to constrain behavior. Nowhere is this more powerfully demonstrated than through current events around online shaming and cyber harassment. Low cost, anonymous, instant, and ubiquitous access to the Internet has removed most—if not all—of the natural checks on shaming. The result is norm enforcement that is indeterminate, uncalibrated, and often tips into behavior punishable in its own right—thus generating a debate over whether the state should intervene to curb online shaming and cyber harassment. A few years before this change in technology, a group of legal scholars debated just the opposite, discussing the value of harnessing the power of social norm enforcement through shaming by using state shaming sanctions as a more efficient means of criminal punishment. Though the idea was discarded, many of their concerns were prescient and can inform today’s inverted new inquiry: whether the state should create limits on shaming and cyber bullying. -

Can Literary Studies Survive? ENDGAME

THE CHRONICLE REVIEW CHRONICLE THE Can literary survive? studies Endgame THE CHRONICLE REVIEW ENDGAME CHRONICLE.COM THE CHRONICLE REVIEW Endgame The academic study of literature is no longer on the verge of field collapse. It’s in the midst of it. Preliminary data suggest that hiring is at an all-time low. Entire subfields (modernism, Victorian poetry) have essentially ceased to exist. In some years, top-tier departments are failing to place a single student in a tenure-track job. Aspirants to the field have almost no professorial prospects; practitioners, especially those who advise graduate students, must face the uneasy possibility that their professional function has evaporated. Befuddled and without purpose, they are, as one professor put it recently, like the Last Di- nosaur described in an Italo Calvino story: “The world had changed: I couldn’t recognize the mountain any more, or the rivers, or the trees.” At the Chronicle Review, members of the profession have been busy taking the measure of its demise – with pathos, with anger, with theory, and with love. We’ve supplemented this year’s collection with Chronicle news and advice reports on the state of hiring in endgame. Altogether, these essays and articles offer a comprehensive picture of an unfolding catastrophe. My University is Dying How the Jobs Crisis Has 4 By Sheila Liming 29 Transformed Faculty Hiring By Jonathan Kramnick Columbia Had Little Success 6 Placing English PhDs The Way We Hire Now By Emma Pettit 32 By Jonathan Kramnick Want to Know Where Enough With the Crisis Talk! PhDs in English Programs By Lisi Schoenbach 9 Get Jobs? 35 By Audrey Williams June The Humanities’ 38 Fear of Judgment Anatomy of a Polite Revolt By Michael Clune By Leonard Cassuto 13 Who Decides What’s Good Farting and Vomiting Through 42 and Bad in the Humanities?” 17 the New Campus Novel By Kevin Dettmar By Kristina Quynn and G. -

Social Media and the Schoolgirl: Performance, Power and Resistance

Social media and the schoolgirl: performance, power and resistance A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. 2019 Jessica Faye Heal Manchester Institute of Education School of Environment, Education and Development Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures .................................................................................... 4 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ 7 About the author .................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 9 Background .......................................................................................................... 12 School Site Reflections ....................................................................................... 18 Thesis Overview .................................................................................................. 19 2. Literature review ....................................................................................... 25 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 25 Defining Social Media ......................................................................................... -

A Content Analysis of #Womenagainstfeminism on Twitter

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2015 "Because I Shave My Armpits…": A Content Analysis of #WomenAgainstFeminism on Twitter Marina Brandman University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Brandman, Marina, ""Because I Shave My Armpits…": A Content Analysis of #WomenAgainstFeminism on Twitter" (2015). HIM 1990-2015. 1696. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1696 “BECAUSE I SHAVE MY ARMPITS…”: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF #WOMENAGAINSTFEMINISM ON TWITTER by MARINA L. BRANDMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Sociology in the College of Sciences and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2015 Thesis Chair: Amy Donley, Ph.D ABSTRACT Because of the speed and convenience of Twitter, it has become one of the most widely utilized platforms for breaking news and is often used to raise awareness of current social issues, political happenings, and social injustices. As more women use Twitter and other social media to embrace the feminist label online, an array of criticism has come to surface. A new movement, #WomenAgainstFeminism, has become popular with Twitter users who reject feminism ideals and the feminism label. -

Sexual Terms / Sexual Tropes PLAY

CLC 1023: Sex and Culture Lecture Two: Sexual Terms / Sexual Tropes PLAY (while class is coming in): “Honey, Honey” by the Archies (1969) Slide 1: Title – Lecture #2: Terms and Tropes Slide 2: Announcements 1. Course Guidebook (Syllabus) –> PDF file now posted on WebCT Owl [can be printed] 2. Lecture notes + Powerpoints posted on WebCT Owl [see me after class for a demo]. 3. Lecture notes will be posted on the course website after each lecture [NB: it may take a day or two to appear, but normally it’s just a few hours.] Slide 3: Policy on Submission of Assignments No reading assignments this week –> but I did suggest last class that you read over the course guidebook carefully. I’d like to focus in on one important aspect of the course today, the Submission Policy for Assignments. Slide 4: Policy cont’d There are FOUR short written assignments for the course: two assignments per term. Assignments handed in on the Official Due Date (see schedule below) will receive a grade plus written comments. Slide 5: Policy cont’d If for any reason you’re unable to submit your work on the Official Due Date, you are automatically granted an extension of two weeks in which to complete the assignment. You do not have to ask for this extension. Assignments handed in on the Extended Due Date will receive a grade without written comments. Work worth an A will receive an A regardless of which due date it’s submitted on: in other words, no marks will ever be subtracted from an assignment simply because you have opted to submit it on the appropriate Extended Due Date. -

72 Years After Death, World War II Fighter Comes Home

New Charge for Mother of Baby $1 Weekend Edition With Meth in Saturday, System / Main 5 July 8, 2017 Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com Fox Theatre Progress Lewis County Coffee Co. South Wall Rebuild Underway as Group Chehalis Business Challenges Customers to Step Hopes for More State Funding / Main 7 Outside Their Comfort Zones on Coffee / Main 4 Sheriff ’s 72 Years After Death, World Office: Man War II Fighter Comes Home Killed in William James Gray Jr.’s Remains to Be Buried Randle Next to Friend Who Kept Wartime Promise Allegedly Shot First AUTOPSY COMPLETED: Victim’s Name Not Released Pending Positive Identification By The Chronicle A man shot and killed Tues- day evening in Randle allegedly fired the first shots in the con- frontation, witnesses told the Lewis County Sheriff’s Office. An autopsy was completed Friday on the man, tentatively identified based on information found at the scene as a 51-year- old transient, according to the Sheriff’s Office. please see SHOT, page Main 9 Inslee Vetoes Tax Break Plan for Pete Caster / [email protected] Above: Jeanne Louvier, left, looks on as her daughter, Jan Bradshaw, flips through a scrapbook compiled by Louvier’s mother of her son’s correspondence while serving Businesses in Europe during World War II. Army Air Force 1st Lt. William “Bill” James Gray, Jr., Louvier’s older brother, died while serving in Germany on April 16, 1945. Top Left: William “Bill” James Gray Jr. is seen in a photograph provided by his family. REJECTED: Deal Would Have Allowed MILITARY HONORS: Family Learns Manufacturers to of Man’s Heroism Through a Have the Same B&O Scrapbook After Remains of Fighter Rate as Businesses Pilot Found in Germany Such as Boeing By Eric Schwartz OLYMPIA (AP) — A plan to [email protected] give manufacturers the same tax cut that the Legislature previ- As World War II tore nations and families apart, ously gave to Boeing was vetoed two best friends in Washington proudly rose to the by Gov.