From With–In the Black Diamond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Express Yourself in New Ways” – Wait, Not Like That

“Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that A semiotic analysis of norm-breaking pictures on Instagram COURSE: Thesis in Media and Communication science II 15 credits PROGRAM: Media and Communication science AUTHORS: Andrea Bille Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen EXAMINER: Peter Berglez SEMESTER: FS2020 Title: “Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that Semester: FS2020 Authors: Andrea Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen Supervisor: Leon Barkho Abstract Instagram, as one of today’s largest social media platforms, plays a significant part in the maintaining and reproducing of existing stereotypes and role expectations for women. The purpose of the thesis is to study how Instagram interprets violations against its guidelines, and whether decisions to remove certain pictures from the platform are in line with terms of use, or part of human subjectivity. The noticeable pattern among the removed pictures is that they are often norm-breaking. The thesis discusses communication within Instagram to reveal how and why some pictures are removed while others are not, which limits women’s possibilities to express themselves in non-conventional settings. The study applies semiotics to analyse 12 pictures that were banned from the platform without directly violating its guidelines. Role theory and norms are used to supplement semiotics and shed light on the underlying societal structures of female disadvantage. Two major conclusions are presented: 1) Instagram has unclearly communicated its guidelines to women’s disadvantage, and 2) Instagram has therefore been subjective in the decisions to have the pictures removed from the platform, also to women’s disadvantage. Further, the discussion focuses on how Instagram handles issues related to (1) female sexuality, (2) women stereotyping, and (3) female self-representation. -

Lagniappe Spring 2015

Junior League of New Orleans LagniappeLagniappeSpring 2015 The 10th Annual Kitchen Tour JLNO and featuring the Idea Village House Beautiful Collaborate on Kitchen of the Big Ideas Year SUSTAINER OF THE YEAR: PEGGY LECORGNE LABORDE When you need to find a doctor in new orleans, touro makes it easy. We can connect you to hundreds of experienced physicians, from primary care providers to OB-GYNs Find a doctor to specialists across the spectrum. close to you. Offices are conveniently located throughout the New Orleans area. Visit touro.com/findadoc, or talk to us at (504) 897-7777. touro.com/Findadoc Boy and Girls Pre-K – 12 Ages 1 – 4 All-Girls’ Education 1538 Philip Street 2343 Prytania Street (504) 523-9911 (504) 561-1224 LittleGate.com McGeheeSchool.com Little Gate is open to all qualified girls and boys regardless of race, religion, national or ethnic origin. Louise S. McGehee School is open to all qualified girls regardless of race, religion, national or ethnic origin. www.jlno.org 1 2014-2015 The Hainkel Home 612 Henry Clay Avenue Lagniappe Staff New Orleans, LA 70118 Editor Kelly Walsh Phone : 504-896-5900 Fax: 504-896-5984 Assistant Editor “They have an exemplary quality assurance program… I suspect the Hainkel Home Amanda Wingfield Goldman is one of the best nursing homes in the state of Louisiana… This is a home that the Writers city of New Orleans needs, desperately needs.” – Dr. Brobson Lutz Mary Audiffred Rebecca Bartlett TIffanie Brown Ann Gray Conger New Parkside Red Unit Heather Guidry Heather Hilliard Services Include: Jacqueline Stump • Private and Semi- Private Rooms Lea Witkowski-Purl • Skilled Services including Photographers Speech, Physical, Occupational Denyse Boudreaux Therapy Jennifer Capitelli Kathleen Dennis • Licensed Practical and Registered Melissa Guidry Nurses on duty 24 hours a day. -

Training Manual

TRAINING MANUAL For sensitizing intermediaries on sexual rights of young people with learning disabilities Abstract This manual has been developed for organizations who wish to educate and sensitize staff, teachers and carers about the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of young people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Although it mainly focuses on intermediaries that are staff in an institution for young people with learning disabilities, it may well also be appropriate as a programme for the parents and family of young people with learning disabilities This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Daphne III Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of IPPF European Network and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. 2 Manual for Sensitizing Intermediaries On sexual rights of young people with learning disabilities About the manual Who is it for? This manual has been developed for organizations who wish to educate and sensitize staff, teachers and carers about the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of young people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Although it mainly focuses on intermediaries that are staff in an institution for young people with learning disabilities, it may well also be appropriate as a programme for the parents and family of young people with learning disabilities. What is its purpose? The manual outlines the main themes to be covered in a training programme for intermediaries of young people with learning disabilities, and suggests exercises to discuss these themes. -

Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from Rupaul's Drag Race

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 3 Feminist Comforts and Considerations amidst a Global Pandemic: New Writings in Feminist and Women’s Studies—Winning and Article 3 Short-listed Entries from the 2020 Feminist Studies Association’s (FSA) Annual Student Essay Competition May 2020 Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race Phoebe Chetwynd Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chetwynd, Phoebe (2020). Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(3), 22-35. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss3/3 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race By Phoebe Chetwynd1 Abstract The popularity of the reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race is often framed as evidence of Western societies’ increasing tolerance towards queer identities. This paper instead considers the ideological cost of this mainstream success, arguing that the show does not successfully challenge dominant heteronormative values. In light of Rosalind Gill’s work on postfeminism, it will be argued that the show’s format calls upon contestants (and viewers) to conform to a postfeminist ideal that valorises normative femininity and reaffirms the gender binary. -

Scissoring Dick Booty Call Sad Handjob

DIRTY BINGO BOOTY SAD SCISSORING DICK BOOBS CALL HANDJOB DOGGIE DEEPTHROAT SEX JIZZ WANKER STYLE FREE STIFFY TEASE SEXY ANAL G-SPOT STRAP QUEEF PISS LICK ORGASM ON GLORY BLOW MILF BONDAGE STROKE HOLE JOB This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 47 events. 69, ANAL, ASS, BACK DOOR, BITCH, BLOW JOB, BONDAGE, BOOBS, BOOTY CALL, CAMEL TOE, CLIMAX, COCK, CUM, CUNNILINGUS, DEEPTHROAT, DICK, DILDO, DOGGIE STYLE, FINGERING, GLORY HOLE, HORNY, HOT, JIZZ, LICK, LUBE, MILF, NIPPLES, ORGASM, PISS, PRICK, QUEEF, SAD HANDJOB, SCISSORING, SEX, SEXY, SHAFT, SPANK, STIFFY, STRAP ON, STROKE, TEASE, THREESOME, TICKLE, TWAT, VA-J-J, VIBRATOR, WANKER. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved DIRTY BINGO PRICK SPANK JIZZ THREESOME TWAT BOOTY BACK SEX SEXY VIBRATOR CALL DOOR FREE CAMEL COCK CLIMAX HOT G-SPOT TOE STRAP STROKE BOOBS ANAL 69 ON CUM STIFFY ASS PISS MILF This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 47 events. 69, ANAL, ASS, BACK DOOR, BITCH, BLOW JOB, BONDAGE, BOOBS, BOOTY CALL, CAMEL TOE, CLIMAX, COCK, CUM, CUNNILINGUS, DEEPTHROAT, DICK, DILDO, DOGGIE STYLE, FINGERING, GLORY HOLE, HORNY, HOT, JIZZ, LICK, LUBE, MILF, NIPPLES, ORGASM, PISS, PRICK, QUEEF, SAD HANDJOB, SCISSORING, SEX, SEXY, SHAFT, SPANK, STIFFY, STRAP ON, STROKE, TEASE, THREESOME, TICKLE, TWAT, VA-J-J, VIBRATOR, WANKER. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved. -

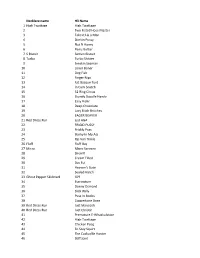

Who Cuming List As 7 18 13.Xlsx

Necklace name H3 Name 1 High Twattage High Twattage 2 Two Fisted Hose Master 3 Take it Lik a Man 4 Stinkin Pussy 5 Nut N Honey 6 Penis Butter 7 S Biscuit Semen Biscuit 8 Turbo Turbo Shitter 9 Smokin Seaman 10 Loner Boner 11 Dog Fish 12 Finger Nips 13 Fat Basque Turd 14 In Cum Snatch 15 32 Ring Circus 16 Skandy Doodle Handy 17 Easy Rider 18 Deep Chocolate 19 Lacy Bitch Britches 20 EAGER BEAVER 21 Red Dress Run just AGA 22 FRIGID PUSSY 23 Prickly Puss 24 Stinky In My Ass 25 Rip Van Tinkle 26 Fluff Fluff Boy 27 Micro Micro Screwry 28 Sherriff 29 Cream Filled 30 Das Fut 31 Heaven's Gate 32 Sealed Hatch 33 Ghost Pepper Skidmark GPS 34 Escrowtum 35 Donny Osmond 36 Slick Willy 37 Puss In Boobs 38 Coppertone Bone 39 Red Dress Run Just Maneesh 40 Red Dress Run Just Christin 41 Premature E-Whackulation 42 High Twattage 43 Chicken Poop 44 Sit Stay Squirt 45 The Cockodile Hunter 46 Stiff Joint 47 Deep Throat 48 Chicken Cox 49 Whaleboner 50 Brown vs The Board of Fornication 51 Beef Eater 52 Dick Shavin's Vagina Juice 53 Cheeky Cheek-a-Boo 54 Ganjaman 55 Easy Going 56 BMW BMW 57 All Sticky All Sticky 58 Close 2 Uranus 59 I Could Have Had a Blowjob 60 Shady Curtains 61 Jacuzzi Douche Me 62 Furry Mason 63 Village Tool 64 Stiff On Trail 65 The Little Spermaid 66 BORT BORT 67 Nookie Monster 68 Red Dress Run just thomas 69 Red Dress Run just jeannine 70 Redwood Floors 71 Turd Bird 72 Go Go Dancer 73 Howdy Howdy Do Me 74 Blinded by Boobs 75 Red Dress Run Just Angela 76 Mas Penis 77 Rectum Rider 78 Surf N Turf 79 Air Whores One 80 SMD SMD 81 Flip Flop Flip -

Sexual Terms / Sexual Tropes PLAY

CLC 1023: Sex and Culture Lecture Two: Sexual Terms / Sexual Tropes PLAY (while class is coming in): “Honey, Honey” by the Archies (1969) Slide 1: Title – Lecture #2: Terms and Tropes Slide 2: Announcements 1. Course Guidebook (Syllabus) –> PDF file now posted on WebCT Owl [can be printed] 2. Lecture notes + Powerpoints posted on WebCT Owl [see me after class for a demo]. 3. Lecture notes will be posted on the course website after each lecture [NB: it may take a day or two to appear, but normally it’s just a few hours.] Slide 3: Policy on Submission of Assignments No reading assignments this week –> but I did suggest last class that you read over the course guidebook carefully. I’d like to focus in on one important aspect of the course today, the Submission Policy for Assignments. Slide 4: Policy cont’d There are FOUR short written assignments for the course: two assignments per term. Assignments handed in on the Official Due Date (see schedule below) will receive a grade plus written comments. Slide 5: Policy cont’d If for any reason you’re unable to submit your work on the Official Due Date, you are automatically granted an extension of two weeks in which to complete the assignment. You do not have to ask for this extension. Assignments handed in on the Extended Due Date will receive a grade without written comments. Work worth an A will receive an A regardless of which due date it’s submitted on: in other words, no marks will ever be subtracted from an assignment simply because you have opted to submit it on the appropriate Extended Due Date. -

Court of Appeals Second District of Texas Fort Worth

COURT OF APPEALS SECOND DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH NOS. 02-09-00375-CR 02-09-00376-CR 02-09-00377-CR 02-09-00378-CR JOHN ALLEN APPELLANT CROSTHWAIT V. THE STATE OF TEXAS STATE ------------ FROM CRIMINAL DISTRICT COURT NO. 4 OF TARRANT COUNTY ------------ MEMORANDUM OPINION1 ------------ I. Introduction In two points, Appellant John Allen Crosthwait appeals his convictions and punishment for possession of child pornography and possession with intent to 1See Tex. R. App. P. 47.4. promote child pornography. See Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 43.26(a), (e) (Vernon 2003). We affirm. II. Factual and Procedural History A tip from America Online (AOL) to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children about an image of child pornography being transmitted from a Texas-based AOL account eventually led to a jury finding Crosthwait guilty of three counts of possession of child pornography and five counts of possession of child pornography with intent to distribute.2 The jury assessed punishment at ten years’ confinement for each possession conviction and twenty years’ confinement for each possession-with-intent-to-distribute conviction. The trial court sentenced him accordingly, setting the ten-year sentences to run concurrently with each other but consecutively to the twenty-year sentences, which run concurrently with each other. This appeal followed. III. Challenge to Facial Unconstitutionality In his first point, Crosthwait argues that penal code section 43.26 is facially unconstitutional because it is vague and overbroad, constituting a violation of the First Amendment. However, he acknowledges that he did not challenge the facial constitutionality of the child pornography statute at trial. -

Malign Creativity

Science and Technology Innovation Program MALIGN CREATIVITY HOW GENDER, SEX, AND LIES ARE WEAPONIZED AGAINST WOMEN ONLINE Authors Nina Jankowicz Jillian Hunchak Alexandra Pavliuc Celia Davies Shannon Pierson Zoë Kaufmann Science and Technology Innovation Program January 2021 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 4 Methodology 12 Data Analysis 16 Qualitative Analysis 29 Challenges of Detecting and Enforcing against Gendered and Sexualized Abuse and Disinformation 37 Policy Recommendations 43 Conclusion 48 About the Authors 49 Appendix A: Platform Policy Quick Reference 50 Appendix B: Platform Architecture Quick Reference 51 Appendix C: Keywords used in data collection and analysis 52 Appendix D: Semi-structured interview questions 53 Appendix E: Focus Group Script 53 Endnotes 55 Acknowledgements The research team is grateful for the opportunity to explore this critical topic, which would not have been possible without the support of Jane Harman, Meg King, Liz Newbury, and the Wilson Center staff who supported this proj- ect and its launch. We are also thankful that eleven women took the time to share their often painful experiences with online gendered abuse and disinformation in order to raise awareness about the human toll of these campaigns. b Executive Summary This report strives to build awareness of the direct and indirect impacts of gendered and sexualized disinformation on women in public life, as well as its corresponding impacts on national security and democratic participation. In an analysis of online conversations about 13 female politicians across six social media platforms, totaling over 336,000 pieces of abusive content shared by over 190,000 users over a two-month period, the report defines, quantifies, and evaluates the use of online gendered and sexualized disinformation campaigns against women in politics and beyond. -

Appendix I: All Possible Porn Films with Three Or Less Participants Based on Categories Used on Youporn.Com and Pornhub.Com

Appendix I: All Possible Porn Films With Three Or Less Participants Based On Categories Used On youporn.com and pornhub.com Set-Ups Filming Style: Mise En Scène: Style: 3d college bondage compilation fantasy fetish hd porn homemade funny 7 hentai 9 instructional 9 7 gonzo* ∑ Cr interview 9C outdoor 9C ∑ r ∑ r hardcore 1 pov 1 party 1 rough sex vintage public + sex voyeur + reality + not mentioned webcam romantic 1 = not mentioned 1 non mentioned 1 TOTAL 8 = = 129 TOTAL 10 TOTAL 10 Combinations 512 512 Combinations Combinations 512 x 512 x129 = 33,816,576 Possible Set-Ups Total Possible Participants Male Female Race/Nationality: Race/Nationality: asian asian ebony ebony european european german 8 german 8 indian C1 indian C1 japanese japanese latina latina not mentioned = not mentioned = 8 8 TOTAL 8 Combinations TOTAL 8 Combinations * Hunter S. Thompson would be spinning in his grave. If they hadn’t cremated him. And then red his ashes out of a cannon. Hair: Hair: hairy hairy shaved 3C shaved 3 1 C1 not mentioned = not mentioned = 3 3 TOTAL 3 Combinations TOTAL 3 Combinations Hair Colour: Hair Colour: blonde blonde brunette 4C brunette 4C redhead 1 redhead 1 not mentioned = not mentioned = 4 4 TOTAL 4 Combinations TOTAL 4 Combinations Age: Age: teen milf mature 3 teen 4 C1 C not mentioned = mature 1 3 not mentioned = TOTAL 3 Combinations 4 TOTAL 4 Combinations Characteristics: Characteristics: big ass babe big dick big ass celebrity camel toe not mentioned 8 celebrity 9 8C 9 panties ∑ r panties ∑ Cr 1 pantyhose pantyhose 1 pornstar pornstar -

Adam's Ale Noun. Water. Abdabs Noun. Terror, the Frights, Nerves. Often Heard As the Screaming Abdabs. Also Very Occasionally 'H

A Adam's ale Noun. Water. abdabs Noun. Terror, the frights, nerves. Often heard as the screaming abdabs . Also very occasionally 'habdabs'. [1940s] absobloodylutely Adv. Absolutely. Abysinnia! Exclam. A jocular and intentional mispronunciation of "I'll be seeing you!" accidentally-on- Phrs. Seemingly accidental but with veiled malice or harm. purpose AC/DC Adj. Bisexual. ace (!) Adj. Excellent, wonderful. Exclam. Excellent! acid Noun. The drug LSD. Lysergic acid diethylamide. [Orig. U.S. 1960s] ackers Noun. Money. From the Egyptian akka . action man Noun. A man who participates in macho activities. Adam and Eve Verb. Believe. Cockney rhyming slang. E.g."I don't Adam and Eve it, it's not true!" aerated Adj. Over-excited. Becoming obsolete, although still heard used by older generations. Often mispronounced as aeriated . afto Noun. Afternoon. [North-west use] afty Noun. Afternoon. E.g."Are you going to watch the game this afty?" [North-west use] agony aunt Noun. A woman who provides answers to readers letters in a publication's agony column. {Informal} aggro Noun. Aggressive troublemaking, violence, aggression. Abb. of aggravation. air biscuit Noun. An expulsion of air from the anus, a fart. See 'float an air biscuit'. airhead Noun. A stupid person. [Orig. U.S.] airlocked Adj. Drunk, intoxicated. [N. Ireland use] airy-fairy Adj. Lacking in strength, insubstantial. {Informal} air guitar Noun. An imaginary guitar played by rock music fans whilst listening to their favourite tunes. aks Verb. To ask. E.g."I aksed him to move his car from the driveway." [dialect] Alan Whickers Noun. Knickers, underwear. Rhyming slang, often shortened to Alans . -

1 U.C.L.A. Slang 6

1u.c.l.a. slang 6 ~ 2009 erik blanco emily franklin colleen carmichael alissa swauger I edited by pamela munro UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics Number 24 u.c.l.a. slang 6 u.c.l.a. slang 6 Erik Blanco Colleen Carmichael Emily Franklin Alissa Swauger edited with an Introduction by Pamela Munro Department of Linguistics University of Califomia, Los Angeles 2009 table of contents A Brief Guide to the Dictionary Entries Abbreviations and Symbols 2 Introduction 3 Copyright 2009 by the Regents of the University of California Acknowledgements 19 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America References 20 U.C.L.A. Slang 6 21 a brief guide to the dictionary entries This is a new dictionary of slang words and expressions used at U .C.L.A. in 2008- 09. It is not a complete dictionary of English slang, but a collection of expressions considered by the authors to be particularly characteristic of current U .C.L.A. slang and college slang in general. For additional information about many of the points mentioned he~·e, plus a discussion of the history of our project and the features of U .C.L.A. slang, please see the Introduction. There are two types of entries in our dictionary, main entries and cross-references. Main entries have a minimum of two parts, and may have a number of others. A main entry begins with a slang word or expression (in boldface type), which is followed by its definition. If the entry word has more than one variant form or spelling, the alternative forms are listed together at the beginning of the entry, separated by slashes.