Say Hello to My Little Friend: an Investigation Into the Correlations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Land Rovers?

The Post Your Local Community Magazine Over 4800 copies Number 267 April 2018 Published by PostDatum, 24 Stone Street, Llandovery, Carms SA20 0JP Tel: 01550 721225 The Welsh Festival of Land Rovers at the Spring Festival will feature a broad selection of vehicles covering the Land Rover’s long and varied history. Photo credit: A Kendall / Shenstone Photography LOVE LAND ROVERS? Then you’ll love THE ROYAL WELSH SPRING FESTIVAL THIS YEAR… Land Rover enthusiasts are in for a treat at this year’s As well as a static display of lots of interesting Royal Welsh Spring Festival. vehicles and the opportunity to chat with South Wales Being held at the showground in Llanelwedd, Builth Land Rover Club members, Land Rover owners and Wells on the 19 & 20 May 2018, the festival is excitedly fellow fanatics, you will also be able to enjoy a parade of working with the South Wales Land Rover Club the vehicles in the ring on Saturday afternoon at 5.15pm, (SWLRC) to host the very first Welsh Festival of Land complete with interactive and entertaining commentary. Rovers, to make the 70th anniversary of the launch of The Royal Welsh Spring Festival is a fantastic the Landy. weekend-long celebration of smallholding and rural A huge part of many people’s lives since 1948, the life, packed full of interesting things to see, delicious Land Rover has been used by HM The Queen, Churchill, food and drink, live music, country sports, livestock, Bond, Lara Croft, Steve McQueen, Ben Fogle, Marilyn shopping, demonstrations and fun, Monroe, British Armed Forces, farmers and many more. -

“Express Yourself in New Ways” – Wait, Not Like That

“Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that A semiotic analysis of norm-breaking pictures on Instagram COURSE: Thesis in Media and Communication science II 15 credits PROGRAM: Media and Communication science AUTHORS: Andrea Bille Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen EXAMINER: Peter Berglez SEMESTER: FS2020 Title: “Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that Semester: FS2020 Authors: Andrea Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen Supervisor: Leon Barkho Abstract Instagram, as one of today’s largest social media platforms, plays a significant part in the maintaining and reproducing of existing stereotypes and role expectations for women. The purpose of the thesis is to study how Instagram interprets violations against its guidelines, and whether decisions to remove certain pictures from the platform are in line with terms of use, or part of human subjectivity. The noticeable pattern among the removed pictures is that they are often norm-breaking. The thesis discusses communication within Instagram to reveal how and why some pictures are removed while others are not, which limits women’s possibilities to express themselves in non-conventional settings. The study applies semiotics to analyse 12 pictures that were banned from the platform without directly violating its guidelines. Role theory and norms are used to supplement semiotics and shed light on the underlying societal structures of female disadvantage. Two major conclusions are presented: 1) Instagram has unclearly communicated its guidelines to women’s disadvantage, and 2) Instagram has therefore been subjective in the decisions to have the pictures removed from the platform, also to women’s disadvantage. Further, the discussion focuses on how Instagram handles issues related to (1) female sexuality, (2) women stereotyping, and (3) female self-representation. -

Lagniappe Spring 2015

Junior League of New Orleans LagniappeLagniappeSpring 2015 The 10th Annual Kitchen Tour JLNO and featuring the Idea Village House Beautiful Collaborate on Kitchen of the Big Ideas Year SUSTAINER OF THE YEAR: PEGGY LECORGNE LABORDE When you need to find a doctor in new orleans, touro makes it easy. We can connect you to hundreds of experienced physicians, from primary care providers to OB-GYNs Find a doctor to specialists across the spectrum. close to you. Offices are conveniently located throughout the New Orleans area. Visit touro.com/findadoc, or talk to us at (504) 897-7777. touro.com/Findadoc Boy and Girls Pre-K – 12 Ages 1 – 4 All-Girls’ Education 1538 Philip Street 2343 Prytania Street (504) 523-9911 (504) 561-1224 LittleGate.com McGeheeSchool.com Little Gate is open to all qualified girls and boys regardless of race, religion, national or ethnic origin. Louise S. McGehee School is open to all qualified girls regardless of race, religion, national or ethnic origin. www.jlno.org 1 2014-2015 The Hainkel Home 612 Henry Clay Avenue Lagniappe Staff New Orleans, LA 70118 Editor Kelly Walsh Phone : 504-896-5900 Fax: 504-896-5984 Assistant Editor “They have an exemplary quality assurance program… I suspect the Hainkel Home Amanda Wingfield Goldman is one of the best nursing homes in the state of Louisiana… This is a home that the Writers city of New Orleans needs, desperately needs.” – Dr. Brobson Lutz Mary Audiffred Rebecca Bartlett TIffanie Brown Ann Gray Conger New Parkside Red Unit Heather Guidry Heather Hilliard Services Include: Jacqueline Stump • Private and Semi- Private Rooms Lea Witkowski-Purl • Skilled Services including Photographers Speech, Physical, Occupational Denyse Boudreaux Therapy Jennifer Capitelli Kathleen Dennis • Licensed Practical and Registered Melissa Guidry Nurses on duty 24 hours a day. -

Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur, Chhattisgarh

PT. RAVISHANKAR SHUKLA UNIVERSITY RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH FACULTY OF LAW(ORDINANCE No. 179) ORDINANCE, SCHEME OF EXAM AND SYLLABUS OF B.A.LL.B. (FIVE YEAR INTEGRATED DEGREE COURSE) SEMESTER SYSTEM EXAMINATION 2014-15 PUBLISHED BY SCHOOL OF P.G. STUDIES AND RESEARCH IN LAW FOR REGISTRAR PT. RAVISHANKAR SHUKLA UNIVERSITY RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH 1 Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur, Chhattisgarh Revised ordinance No.179 B.A.LL.B. FIVE YEARS INTEGRATED DEGREE COURSE (Semester System) 1. The whole period of this integrated B.A.LL.B course divided into five academic years/ classes known as B.A.LL.B Semester first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eight, ninth and tenth semesters respectively. Every year /class is divided into Two Semesters WINTER and SUMMER Semesters. The examination of winter semester of all the classes will be called as WINTER TERM EXAMINATION and the other one would be known as SUMMER TERM EXAMINATION. In other words the course is extended into TEN SEMESTERS. The winter semesters are known as ODD semesters ( I, III, V, VII , IX ) while the summer semesters are known as EVEN semesters ( II, IV, VI, VIII , X ). 2. The details syllabus/ course of studies for each semester/ academic year and marking scheme for examination, etc. for this course shall be framed and approved by the Board of Studies and Law faculty duly constituted in accordance with the provision of the University Statute and Act. The syllabus forming bodies can amend/ modify the syllabus if needed in the light of BCI norms, time to time. 3. The semester academic schedule shall be framed by the University authorities according to the guidelines of BCI, and may be changed if needed. -

Training Manual

TRAINING MANUAL For sensitizing intermediaries on sexual rights of young people with learning disabilities Abstract This manual has been developed for organizations who wish to educate and sensitize staff, teachers and carers about the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of young people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Although it mainly focuses on intermediaries that are staff in an institution for young people with learning disabilities, it may well also be appropriate as a programme for the parents and family of young people with learning disabilities This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Daphne III Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of IPPF European Network and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. 2 Manual for Sensitizing Intermediaries On sexual rights of young people with learning disabilities About the manual Who is it for? This manual has been developed for organizations who wish to educate and sensitize staff, teachers and carers about the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of young people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Although it mainly focuses on intermediaries that are staff in an institution for young people with learning disabilities, it may well also be appropriate as a programme for the parents and family of young people with learning disabilities. What is its purpose? The manual outlines the main themes to be covered in a training programme for intermediaries of young people with learning disabilities, and suggests exercises to discuss these themes. -

Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from Rupaul's Drag Race

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 3 Feminist Comforts and Considerations amidst a Global Pandemic: New Writings in Feminist and Women’s Studies—Winning and Article 3 Short-listed Entries from the 2020 Feminist Studies Association’s (FSA) Annual Student Essay Competition May 2020 Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race Phoebe Chetwynd Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chetwynd, Phoebe (2020). Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(3), 22-35. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss3/3 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race By Phoebe Chetwynd1 Abstract The popularity of the reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race is often framed as evidence of Western societies’ increasing tolerance towards queer identities. This paper instead considers the ideological cost of this mainstream success, arguing that the show does not successfully challenge dominant heteronormative values. In light of Rosalind Gill’s work on postfeminism, it will be argued that the show’s format calls upon contestants (and viewers) to conform to a postfeminist ideal that valorises normative femininity and reaffirms the gender binary. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

A Republic of Lost Peoples: Race, Status, and Community in the Eastern Andes of Charcas at the Turn of the Seventeenth Century A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Nathan Weaver Olson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Sarah C. Chambers August 2017 © Nathan Weaver Olson 2017 Acknowledgements There is a locally famous sign along the highway between the Bolivian cities of Vallegrande and El Trigal that marks the turn-off for the town of Moro Moro. It reads: “Don’t say that you know the world if you don’t know Moro Moro.” Although this dissertation began as an effort to study the history of Moro Moro, and more generally the province of Vallegrande, located in the Andean highlands of the department of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the research and writing process has made me aware of an entire world of Latin American history. Thus, any recounting of the many people who have contributed to this project must begin with the people of Moro Moro themselves, whose rich culture and sense of regional identity first inspired me to learn more about Bolivian history. My companions in that early journey, all colleagues from the Mennonite Central Committee, included Patrocinio Garvizu, Crecensia García, James “Phineas” Gosselink, Dantiza Padilla, and Eloina Mansilla Guzmán, to name only a few. I owe my interest and early academic grounding in Colonial Latin American history to my UCSD professors Christine Hunefeldt, Nancy Postero, Eric Van Young, and Michael Monteón. My colleagues at UCSD’s Center for Iberian and Latin American Studies and the Dimensions of Culture Writing Program at UCSD’s Thurgood Marshall College made me a better researcher and teacher. -

Scissoring Dick Booty Call Sad Handjob

DIRTY BINGO BOOTY SAD SCISSORING DICK BOOBS CALL HANDJOB DOGGIE DEEPTHROAT SEX JIZZ WANKER STYLE FREE STIFFY TEASE SEXY ANAL G-SPOT STRAP QUEEF PISS LICK ORGASM ON GLORY BLOW MILF BONDAGE STROKE HOLE JOB This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 47 events. 69, ANAL, ASS, BACK DOOR, BITCH, BLOW JOB, BONDAGE, BOOBS, BOOTY CALL, CAMEL TOE, CLIMAX, COCK, CUM, CUNNILINGUS, DEEPTHROAT, DICK, DILDO, DOGGIE STYLE, FINGERING, GLORY HOLE, HORNY, HOT, JIZZ, LICK, LUBE, MILF, NIPPLES, ORGASM, PISS, PRICK, QUEEF, SAD HANDJOB, SCISSORING, SEX, SEXY, SHAFT, SPANK, STIFFY, STRAP ON, STROKE, TEASE, THREESOME, TICKLE, TWAT, VA-J-J, VIBRATOR, WANKER. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved DIRTY BINGO PRICK SPANK JIZZ THREESOME TWAT BOOTY BACK SEX SEXY VIBRATOR CALL DOOR FREE CAMEL COCK CLIMAX HOT G-SPOT TOE STRAP STROKE BOOBS ANAL 69 ON CUM STIFFY ASS PISS MILF This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 47 events. 69, ANAL, ASS, BACK DOOR, BITCH, BLOW JOB, BONDAGE, BOOBS, BOOTY CALL, CAMEL TOE, CLIMAX, COCK, CUM, CUNNILINGUS, DEEPTHROAT, DICK, DILDO, DOGGIE STYLE, FINGERING, GLORY HOLE, HORNY, HOT, JIZZ, LICK, LUBE, MILF, NIPPLES, ORGASM, PISS, PRICK, QUEEF, SAD HANDJOB, SCISSORING, SEX, SEXY, SHAFT, SPANK, STIFFY, STRAP ON, STROKE, TEASE, THREESOME, TICKLE, TWAT, VA-J-J, VIBRATOR, WANKER. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved. -

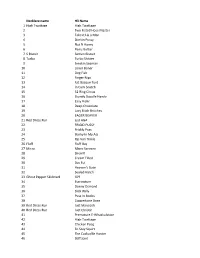

Who Cuming List As 7 18 13.Xlsx

Necklace name H3 Name 1 High Twattage High Twattage 2 Two Fisted Hose Master 3 Take it Lik a Man 4 Stinkin Pussy 5 Nut N Honey 6 Penis Butter 7 S Biscuit Semen Biscuit 8 Turbo Turbo Shitter 9 Smokin Seaman 10 Loner Boner 11 Dog Fish 12 Finger Nips 13 Fat Basque Turd 14 In Cum Snatch 15 32 Ring Circus 16 Skandy Doodle Handy 17 Easy Rider 18 Deep Chocolate 19 Lacy Bitch Britches 20 EAGER BEAVER 21 Red Dress Run just AGA 22 FRIGID PUSSY 23 Prickly Puss 24 Stinky In My Ass 25 Rip Van Tinkle 26 Fluff Fluff Boy 27 Micro Micro Screwry 28 Sherriff 29 Cream Filled 30 Das Fut 31 Heaven's Gate 32 Sealed Hatch 33 Ghost Pepper Skidmark GPS 34 Escrowtum 35 Donny Osmond 36 Slick Willy 37 Puss In Boobs 38 Coppertone Bone 39 Red Dress Run Just Maneesh 40 Red Dress Run Just Christin 41 Premature E-Whackulation 42 High Twattage 43 Chicken Poop 44 Sit Stay Squirt 45 The Cockodile Hunter 46 Stiff Joint 47 Deep Throat 48 Chicken Cox 49 Whaleboner 50 Brown vs The Board of Fornication 51 Beef Eater 52 Dick Shavin's Vagina Juice 53 Cheeky Cheek-a-Boo 54 Ganjaman 55 Easy Going 56 BMW BMW 57 All Sticky All Sticky 58 Close 2 Uranus 59 I Could Have Had a Blowjob 60 Shady Curtains 61 Jacuzzi Douche Me 62 Furry Mason 63 Village Tool 64 Stiff On Trail 65 The Little Spermaid 66 BORT BORT 67 Nookie Monster 68 Red Dress Run just thomas 69 Red Dress Run just jeannine 70 Redwood Floors 71 Turd Bird 72 Go Go Dancer 73 Howdy Howdy Do Me 74 Blinded by Boobs 75 Red Dress Run Just Angela 76 Mas Penis 77 Rectum Rider 78 Surf N Turf 79 Air Whores One 80 SMD SMD 81 Flip Flop Flip -

Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don Mclean 1972 4

AS VOTED AT OLDIESBOARD.COM 10/30/17 THROUGH 12/4/17 CONGRATULATIONS TO “HEY JUDE”, THE #1 SELECTION FOR THE 19 TH TIME IN 20 YEARS! Ti tle Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 Light My Fire Doors 1967 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 7 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 10 Ain't No Mount ain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 11 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 12 Because Dave Clark Five 1964 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Cherish Association 1966 15 She Loves You Beatles 1964 16 Hotel California Eagles 1977 17 St airway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 18 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 19 My Girl Temptations 1965 20 Let It Be Beatles 1970 21 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 22 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 23 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 24 To Sir With Love Lul u 1967 25 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 26 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 27 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 28 You Really Got Me Kinks 19 64 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 The Rain The Park & Ot her Things Cowsills 1967 31 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 1964 32 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 33 Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 34 Imagine John Lennon 1971 35 I Only Have Eyes For You Flamingos 1959 36 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 37 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76 -92 38 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 39 What's -

Male Homosocial Landscape

MALE HOMOSOCIAL LANDSCAPE: FAULKNER,WRIGHT, HEMINGWAY, AND FITZGERALD A dissertation submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Masaya Takeuchi December, 2011 Dissertation written by Masaya Takeuchi B.A., Rikkyo University, 2001 M.A., Rikkyo University, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by Robert Trogdon , Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Mark Bracher , Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kevin Floyd , Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Elizabeth M. Smith-Pryor , Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Marilyn A. Norconk , Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by Donald M. Hassler , Interim Chair, English Department Timothy Moerland , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ……………………………………………………………………….iv Introduction …………………………………………………….………………………. 1 Part I: Chapter 1. ………………………………………………………………………………. 26 2. …………………..…………………………………………………………... 59 Part II: Chapter 3. ………………...……………………………………………………………... 93 Part III: Chapter 4. ……………...……………………………………………………………… 122 5. ………..……………………………………………………………………. 163 Part IV: Chapter 6. ……...……………………………………………………………………… 190 7. ……………………………………………………………………………... 225 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………….. 254 Bibliography ….………………………………………..……………………………..... 261 iii Acknowledgements During the eight years I have studied in Ph.D. programs at Rikkyo University and Kent State University, I have received tremendous instruction and encouragement from many professors. -

Sexual Terms / Sexual Tropes PLAY

CLC 1023: Sex and Culture Lecture Two: Sexual Terms / Sexual Tropes PLAY (while class is coming in): “Honey, Honey” by the Archies (1969) Slide 1: Title – Lecture #2: Terms and Tropes Slide 2: Announcements 1. Course Guidebook (Syllabus) –> PDF file now posted on WebCT Owl [can be printed] 2. Lecture notes + Powerpoints posted on WebCT Owl [see me after class for a demo]. 3. Lecture notes will be posted on the course website after each lecture [NB: it may take a day or two to appear, but normally it’s just a few hours.] Slide 3: Policy on Submission of Assignments No reading assignments this week –> but I did suggest last class that you read over the course guidebook carefully. I’d like to focus in on one important aspect of the course today, the Submission Policy for Assignments. Slide 4: Policy cont’d There are FOUR short written assignments for the course: two assignments per term. Assignments handed in on the Official Due Date (see schedule below) will receive a grade plus written comments. Slide 5: Policy cont’d If for any reason you’re unable to submit your work on the Official Due Date, you are automatically granted an extension of two weeks in which to complete the assignment. You do not have to ask for this extension. Assignments handed in on the Extended Due Date will receive a grade without written comments. Work worth an A will receive an A regardless of which due date it’s submitted on: in other words, no marks will ever be subtracted from an assignment simply because you have opted to submit it on the appropriate Extended Due Date.