Alam: Violence Against Women in Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KON 4Th Edition Spring 2019

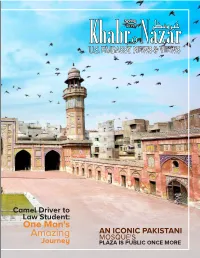

Spring Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's AN ICONIC PAKISTANI Amazing MOSQUE'S Journey PLAZA IS PUBLIC ONCE MORE SPRING EDITION Editor in Chief Christopher Fitzgerald – Minister Counselor for Public Affairs Managing Editor Richard Snelsire – Embassy Spokesperson Associate Editor Donald Cordell, Wasim Abbas Background Khabr-o-Nazar is a free magazine published by U.S. Embassy, Islamabad Stay Connected Khabr-o-Nazar, Public Affairs Section U.S. Embassy, Ramna 5, Diplomatic Enclave Islamabad, Pakistan Email [email protected] Website http://pk.usembassy.gov/education.culture/khabr_o_nazar.html Magazine is designed & printed by GROOVE ASSOCIATES Telephone: 051-2620098 Mobile: 0345-5237081 flicker.com/photos www.youtube.com/- @usembislamabad www.facebook.com/ www.twitter.com/use- /usembpak c/usembpak pakistan.usembassy mbislamabad CCoonnttenentt 04 EVENTS 'Top Chef' Contestant Fatima Ali 06 on How Cancer Changed A CHAT WITH the Way She Cooks ACTING DEPUTY ASSISTANT SECRETARY 08 HENRY ENSHER A New Mission Through a unique summer camp iniave, Islamabad's police forge bonds with their communies — one family at a me 10 Cities of the Sun Meet Babcock Ranch, a groundbreaking model 12 for sustainable communies of the future. Young Pakistani Scholars Preparing to Tackle Pakistan's 14 Energy Crisis Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's 16 Amazing Journey Consular Corner Are you engaged to or dang a U.S. cizen? 18 An Iconic Pakistani Mosque’s Plaza 19 Is Public Once More From February 25 to March 8, English Language Specialist Dr. Loe Baker, conducted a series of professional development workshops for English teachers from universies across the country. -

Radical Feminism and Its Major Socio-Religious Impact… 45 Radical Feminism and Its Major Socio-Religious Impact (A Critical Analysis from Islamic Perspective) Dr

Radical Feminism and its Major Socio-Religious Impact… 45 Radical Feminism and its Major Socio-Religious Impact (A Critical Analysis from Islamic Perspective) Dr. Riaz Ahmad Saeed Dr. Arshad Munir Leghari ** ABSTRACT Women’s rights and freedom is one of the most debated subjects and the flash point of contemporary world. Women maintain a significant place in the society catered to them not only by the modern world but also by religion. Yet, the clash between Islamic and western civilization is that they have defined different set of duties for them. Islam considers women an important participatory member of the society by assigning them inclusive role, specifying certain fields of work to them, given the vulnerability they might fall victim to. Contrarily, Western world allows women to opt any profession of their choice regardless of tangible threats they may encounter. Apparently, the modern approach seems more attractive and favorable, but actually this is not plausible from Islamic point of view. Intermingling, co-gathering and sexual attraction of male and female are creating serious difficulties and problems for both genders, especially for women. Women are currently running many movements for their security, rights and liberties under the umbrella of “Feminism”. Due to excess of freedom and lack of responsibility, a radical movement came into existence which was named as ‘Radical Feminism’. This feminist movement is affecting the unique status of women in the whole world, especially in the west. This study seeks to explore radical feminism and its major impact on socio-religious norms in addition to its critical analysis from an Islamic perspective. -

“Express Yourself in New Ways” – Wait, Not Like That

“Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that A semiotic analysis of norm-breaking pictures on Instagram COURSE: Thesis in Media and Communication science II 15 credits PROGRAM: Media and Communication science AUTHORS: Andrea Bille Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen EXAMINER: Peter Berglez SEMESTER: FS2020 Title: “Express yourself in new ways” – wait, not like that Semester: FS2020 Authors: Andrea Pettersson, Aino Vauhkonen Supervisor: Leon Barkho Abstract Instagram, as one of today’s largest social media platforms, plays a significant part in the maintaining and reproducing of existing stereotypes and role expectations for women. The purpose of the thesis is to study how Instagram interprets violations against its guidelines, and whether decisions to remove certain pictures from the platform are in line with terms of use, or part of human subjectivity. The noticeable pattern among the removed pictures is that they are often norm-breaking. The thesis discusses communication within Instagram to reveal how and why some pictures are removed while others are not, which limits women’s possibilities to express themselves in non-conventional settings. The study applies semiotics to analyse 12 pictures that were banned from the platform without directly violating its guidelines. Role theory and norms are used to supplement semiotics and shed light on the underlying societal structures of female disadvantage. Two major conclusions are presented: 1) Instagram has unclearly communicated its guidelines to women’s disadvantage, and 2) Instagram has therefore been subjective in the decisions to have the pictures removed from the platform, also to women’s disadvantage. Further, the discussion focuses on how Instagram handles issues related to (1) female sexuality, (2) women stereotyping, and (3) female self-representation. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Women in Pakistan: Change Is Imminent

The 29th Foreign Correspondent Report Women in Pakistan: Change is imminent Ms. Shabana Mahfooz (Pakistan) Last year, a women’s rights activist in the southern province of Pakistan was murdered by her husband because he disapproved of her activism and her participation in the international women’s day rally, Aurat March. Aurat means ‘woman’ in Urdu, the national language of Pakistan. This year, organizers of the Aurat March received death threats for allowing women to participate, holding placards with bold statements in retaliation against body shaming, patriarchy and abuse against women of all kinds – to name a few. The women who participated in turn were the focus of severe backlash particularly on social media and were ridiculed and trolled for their brazen attitudes. Among all conclusions drawn and judgements made, one stands out: the fight between patriarchy and women’s rights in Pakistan still has a long way to go. With an increase in awareness and to some extent, literacy, with roughly 50 percent of the female population in the country educated, activism among women is on the rise. This is a much desired situation. The country’s lawmakers are still engaged in a debate to raise the minimum marriageable age for girls to 18. Education for girls in many areas of the country is still considered unnecessary or even immoral. ‘Honour killings’ are to date prevalent in many tribal and even urban areas, where a woman may be murdered, raped or paraded naked to avenge her family’s honour tarnished by another, with the woman herself often having no role in the dishonourable act. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia Zahra F. Syed The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3785 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEVOTIONAL LITERATURE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD IN SOUTH ASIA by ZAHRA SYED A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in [program] in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 ZAHRA SYED All Rights Reserved ii Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia by Zahra Syed This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Middle Eastern Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. _______________ _________________________________________________ Date Kristina Richardson Thesis Advisor ______________ ________________________________________________ Date Simon Davis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia by Zahra Syed Advisor: Kristina Richardson Many Sufi poets are known for their literary masterpieces that combine the tropes of love, religion, and the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). In a thorough analysis of these works, readers find that not only were these prominent authors drawing from Sufi ideals to venerate the Prophet, but also outputting significant propositions and arguments that helped maintain the preservation of Islamic values, and rebuild Muslim culture in a South Asian subcontinent that had been in a state of colonization for centuries. -

Statement of Ali Dayan Hasan Pakistan Director, Human Rights Watch

Statement of Ali Dayan Hasan Pakistan Director, Human Rights Watch: House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations February 8, 2012 Hearing on Balochistan Balochistan: An overview Balochistan, Pakistan’s western-most province, borders eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan. It is the largest of the country’s four provinces in terms of area (44 percent of the country’s land area), but the smallest in terms of population (5 percent of the country’s total). According to the last national census in 1998, over two-thirds of its population of nearly eight million people live in rural areas.1 The population comprises those whose first language—an important marker of ethnic distinction in Pakistan—is Balochi (55 percent), Pashto (30 percent), Sindhi (5.6 percent), Seraki (2.6 percent), Punjabi (2.5 percent), and Urdu (1 percent).2 There are three distinct geographic regions of Balochistan. The belt comprising Hub, Lasbella, and Khizdar in the east is heavily influenced by the city of Karachi, Pakistan’s sprawling economic center in Sindh province. The coastal belt comprising Makran is dominated by Gwadar port. Eastern Balochistan is the most remote part of the province. This sparsely populated region is home to the richest but largely untapped deposits of natural resources in Pakistan including oil, gas, copper, and gold. Significantly, it is the area where the struggle for power between the Pakistani state and local tribal elites has been most apparent.3 Balochistan is both economically and strategically important: not only does the province border Iran and Afghanistan, it hosts a particular ethnic mix of residents, and is allegedly home to the so-called Quetta Shura of the Taliban in the provincial capital Quetta.4 The situation is further complicated by the large number of foreign states with an economic or 1 Census of Pakistan 1998, Balochistan Provincial Report; and World Bank, Balochistan Economic Report: From Periphery To Core, Volume II, 2008. -

Karachi's Deadly Unrest

افغانستان آزاد – آزاد افغانستان AA-AA چو کشور نباشـد تن من مبـــــــاد بدین بوم وبر زنده یک تن مــــباد همه سر به سر تن به کشتن دهیم از آن به که کشور به دشمن دهیم www.afgazad.com [email protected] زبان های اروپائی European Languages http://thediplomat.com/2015/05/karachis-deadly-unrest/ Karachi’s Deadly Unrest A deadly bus attack underscores the tensions roiling Pakistan’s largest city. By Kiyya Baloch May 15, 2015 Despite considerable rhetoric and months of effort, the operations Pakistani paramilitary forces have been carrying out in Karachi still appear to be far short of bring peace to the port city. On Wednesday, six gunmen armed with sophisticated weapons gunned down at least 43 people and wounded 13 others in a busy market in the city. The attackers were able to flee unhurt from the scene. The attackers opened fire inside a bus carrying members of the Ismaili community, a sub-sect of Shiite Muslims known for their liberal views. In the wake of the attack came chaos, as mobs took out their anger on local police. Hundreds of men, women and children took to the streets, blaming Pakistan’s paramilitary forces and police for not targeting Jundullah, which claimed responsibility for the deadly attack. Jundullah is a splinter group of the Pakistani Taliban, allegedly based in a Pakistani tribal area and Quetta. According to senior Pakistani journalist Umar Farooq, Jundullah has very strong links with the Islamic State (IS), pledging allegiance in a November 2014 video message. Asked about the attack, Gulam Haider Jamali, Sindh Police Chief said, “We are in the process of investigation, if it was a security lapse we will act against police officers within the parameters www.afgazad.com 1 [email protected] of the Constitution. -

Crisis Response Bulletin

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN May 04, 2015 - Volume: 1, Issue: 16 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 3-24 SHC takes notice of non-provision of relief goods in drought-hit areas 03 Modi proposes SAARC team to tackle natural disasters.. As Pakistan's 05 PM commends India's Nepal mission Natural Calamities Section 3-9 Natural Disasters: IDA mulling providing $150 million 05 Safety and Security Section 10-15 Pak-Army teams take on relief works in Peshawar 07 Progress reviewed: Safe City Project to be replicated province-wide 10 Public Services Section 16-24 Ensuring peace across country top priority, says PM 10 Afghan refugees evicted 11 Maps 25-31 PEMRA Bars TV Channels from telecasting hateful speeches 12 Protest: Tribesmen decry unfair treatment by political administration 13 officials Urdu News 41-32 Pakistan to seek extradition of top Baloch insurgents 13 Oil Supply: Government wants to keep PSO-PNSC contract intact 16 Natural Calamities Section 41-38 Workers to take to street for Gas, Electricity 17 Electricity shortfall widens to 4300 mw 18 Safety and Security section 37-35 China playing vital role in overcoming Energy Crisis' 19 Public Service Section 34-32 Use of substandard sunglasses causing eye diseases 23 PAKISTAN WEATHER MAP WIND SPEED MAP OF PAKISTAN MAXIMUM TEMPERATURE MAP OF PAKISTAN VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN MAPS CNG SECTOR GAS LOAD MANAGEMENT PLAN-SINDH POLIO CASES IN PAKISTAN CANTONMENT BOARD LOCAL BODIES ELECTION MAP 2015 Cantonment Board Local Bodies Election Map 2015 HUNZA NAGAR C GHIZER H ¯ CHITRAL I GILGIT N 80 A 68 DIAMIR 70 UPPER SKARDU UPPER SWAT KOHISTAN DIR LOWER GHANCHE 60 55 KOHISTAN ASTORE SHANGLA 50 BAJAUR LOWER BATAGRAM NEELUM 42 AGENCY DIR TORDHER MANSEHRA 40 MOHMAND BUNER AGENCY MARDAN MUZAFFARABAD 30 HATTIAN CHARSADDA INDIAN 19 ABBOTTABAD BALA PESHAWAR SWABI OCCUPIED KHYBER BAGH 20 NOWSHERA HARIPUR HAVELI KASHMIR AGENCY POONCH 7 KURRAM FR PESHAWAR 6 ORAKZAI SUDHNOTI 10 2 AGENCY FR KOHAT ISLAMABAD 0 AGENCY ATTOCK HANGU KOHAT KOTLI 0 RAWALPINDI MIRPUR FR BANNU KARAK BHIMBER N.