Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KON 4Th Edition Spring 2019

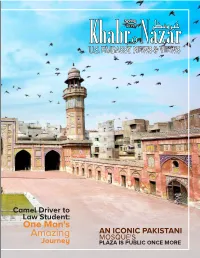

Spring Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's AN ICONIC PAKISTANI Amazing MOSQUE'S Journey PLAZA IS PUBLIC ONCE MORE SPRING EDITION Editor in Chief Christopher Fitzgerald – Minister Counselor for Public Affairs Managing Editor Richard Snelsire – Embassy Spokesperson Associate Editor Donald Cordell, Wasim Abbas Background Khabr-o-Nazar is a free magazine published by U.S. Embassy, Islamabad Stay Connected Khabr-o-Nazar, Public Affairs Section U.S. Embassy, Ramna 5, Diplomatic Enclave Islamabad, Pakistan Email [email protected] Website http://pk.usembassy.gov/education.culture/khabr_o_nazar.html Magazine is designed & printed by GROOVE ASSOCIATES Telephone: 051-2620098 Mobile: 0345-5237081 flicker.com/photos www.youtube.com/- @usembislamabad www.facebook.com/ www.twitter.com/use- /usembpak c/usembpak pakistan.usembassy mbislamabad CCoonnttenentt 04 EVENTS 'Top Chef' Contestant Fatima Ali 06 on How Cancer Changed A CHAT WITH the Way She Cooks ACTING DEPUTY ASSISTANT SECRETARY 08 HENRY ENSHER A New Mission Through a unique summer camp iniave, Islamabad's police forge bonds with their communies — one family at a me 10 Cities of the Sun Meet Babcock Ranch, a groundbreaking model 12 for sustainable communies of the future. Young Pakistani Scholars Preparing to Tackle Pakistan's 14 Energy Crisis Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's 16 Amazing Journey Consular Corner Are you engaged to or dang a U.S. cizen? 18 An Iconic Pakistani Mosque’s Plaza 19 Is Public Once More From February 25 to March 8, English Language Specialist Dr. Loe Baker, conducted a series of professional development workshops for English teachers from universies across the country. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Bibliography

Bibliography Aamir, A. (2015a, June 27). Interview with Syed Fazl-e-Haider: Fully operational Gwadar Port under Chinese control upsets key regional players. The Balochistan Point. Accessed February 7, 2019, from http://thebalochistanpoint.com/interview-fully-operational-gwadar-port-under- chinese-control-upsets-key-regional-players/ Aamir, A. (2015b, February 7). Pak-China Economic Corridor. Pakistan Today. Aamir, A. (2017, December 31). The Baloch’s concerns. The News International. Aamir, A. (2018a, August 17). ISIS threatens China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. China-US Focus. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https://www.chinausfocus.com/peace-security/isis-threatens- china-pakistan-economic-corridor Aamir, A. (2018b, July 25). Religious violence jeopardises China’s investment in Pakistan. Financial Times. Abbas, Z. (2000, November 17). Pakistan faces brain drain. BBC. Abbas, H. (2007, March 29). Transforming Pakistan’s frontier corps. Terrorism Monitor, 5(6). Abbas, H. (2011, February). Reforming Pakistan’s police and law enforcement infrastructure is it too flawed to fix? (USIP Special Report, No. 266). Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Abbas, N., & Rasmussen, S. E. (2017, November 27). Pakistani law minister quits after weeks of anti-blasphemy protests. The Guardian. Abbasi, N. M. (2009). The EU and Democracy building in Pakistan. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https:// www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/the-role-of-the-european-union-in-democ racy-building/eu-democracy-building-discussion-paper-29.pdf Abbasi, A. (2017, April 13). CPEC sect without project director, key specialists. The News International. Abbasi, S. K. (2018, May 24). -

JAHANGIR KHAN (571)-285-8726 | [email protected] |

JAHANGIR KHAN (571)-285-8726 | [email protected] | www.linkedin.com/in/jk0007/ EDUCATION OHIO UNIVERSITY, College of Business - Athens, OH Master of Business Administration and Master of Sport Administration May 2019 ▪ Graduate Assistant, Business Operations Campus Rec Lahore University of Management Sciences - Lahore, Pakistan Bachelors in Economics and Political Science May 2012 EXPERIENCE OHIO UNIVERSITY – Athens, Ohio September 2018 - ongoing Graduate Assistant, Business Operations for Campus Recreation ▪ Managed concessions and re-sale inventory for 5 recreation facilities at Ohio University which included coordinating with facility directors regularly. ▪ Assisted the business manager in preparing and reporting the budget for each facility; created and compared forecast reports for the Exec board. COLUMBUS CREW SC – Athens, Ohio September 2017 – September 2018 Street Marketing Manager, Southeast Ohio ▪ Recruited and managed a team of 15 brand ambassadors and 3 assistant managers for the initiative. ▪ The team sold 526 tickets and generated approximately $8,000 in revenue for Columbus Crew SC through Ohio University night at the MAPFRE stadium. ▪ Promoted Columbus Crew SC and MLS in southeast Ohio, through activation on campus such as tabling sessions, soccer tournaments, watch parties, etc US SOCCER – Sirisota, Florida November 2017 Event Operations ▪ Assisted US Soccer development academy event operations staff for the 2017 Winter showcase. OHIO UNIVERSITY – Athens, Ohio September 2017- May 2017 Graduate Assistant, AECOM Center for Sports Administration ▪ Reported directly to the Director of Sports Administration program working on a variety of projects for the AECOM Center for Sports Administration. ▪ Compiled a comprehensive history document for the oldest sports administration program in the world and performed a competitive analysis of the major sports programs in the US, Canada and Europe. -

Clamor Magazine Po Box 1225 Bowung Green Oh 43402 '

Antibalas * Harry Potter * Bush Family & the 4 Holocaust * Black Hawk Down The Pay^r 06> .edia Empowerment 7 25274 " 96769? IK wait ing for computers to make life easier Eco-Tekorism in Court • Songs for Emma :r4-» May/June 2002 Get 1 Year for just $18 Save over 30% off the cover price. CLAMOR subscribers play an integral role in sustaining this volunteer-run magazine. If you like what you read (or have read) here in CLAMOR, please subscribe! CLAMOR subscribers not only receive a discount off the cover price, but they also receive their magazine before it hits the newsstands and they know that their subscription payment goes directly to supporting future issues of CLAMOR. subscribe online at www.clamormagazine.org or return this coupon! I 1 Consider me a supporter of independent media! O Enclosed is $18 for my subscription O Please charge my Visa/Mastercard for the above amount. exp. _ / (mo/yr) name address email (optional) Return this coupon tO: CLAMOR MAGAZINE PO BOX 1225 BOWUNG GREEN OH 43402 ' ttl ^ftnnro EDITORS Jen Angel Jason Kucsma Hello Everyone! PROOFREADERS This issue we're focusing on youth and culture. And while you may think that we are a bit Hal Hixson, Rich Booher. Amy Jo Brown, old to be considered "youth." we certainly do not feel like adults. Alright, we're only in our late Catherine Gary Phillips. Scott Komp, twenties. Even though Jen, for example, has a full time job. makes car payments, and is. in Puckett, Kristen Schmidt general, very responsible, she still does not feel like a grown-up. -

Repaving the Ancient Silk Routes

PwC Growth Markets Centre – Realising opportunities along the Belt and Road June 2017 Repaving the ancient Silk Routes In this report 1 Foreword 2 Chapter 1: Belt and Road – A global game changer 8 Chapter 2: China’s goals for the Belt and Road 14 Chapter 3: Key sectors and economic corridors 28 Chapter 4: Opportunities for foreign companies 34 Chapter 5: Unique Belt and Road considerations 44 Chapter 6: Strategies to evaluate and select projects 56 Chapter 7: Positioning for success 66 Chapter 8: Leveraging international platforms 72 Conclusion Foreword Belt and Road – a unique trans-national opportunity Not your typical infrastructure projects Few people could have envisaged what the Belt and Road However, despite the vast range and number of B&R (B&R) entailed when President Xi of China first announced opportunities, many of these are developed in complex the concept back in 2013. However, four years later, the B&R conditions, not least because they are located in growth initiative has amassed a huge amount of economic markets where institutional voids can prove to be hard to momentum.The B&R initiative refers to the Silk Road navigate. Inconsistencies in regulatory regimes and Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road underdeveloped credit markets, together with weak existing initiatives. The network connects Asia, Europe and Africa, infrastructure and a maturing talent market all combine to and passes through more than 65 countries and regions with add further complexity for companies trying to deliver and a population of about 4.4 billion and a third of the global manage these projects. -

Gallup TV Ratings Services – the Only National TV Ratings Service

Gallup TV Ratings Services – The Only National TV Ratings Service Star Plus is Pakistan's Most watched Channel among Cable & Satellite Viewers : Gallup TV Ratings Service Dear Readers, Greetings! Gallup TV Ratings Service (the only National TV Ratings Service) released a report on most popular TV Channels in Pakistan. The report is compiled on the basis of the Gallup TV Ratings Services, the only National TV Ratings available for Pakistan. According to the report, Star Plus tops the list and had an average daily reach of around 12 million Cable and Satellite Viewers during the time period Jan- to date (2013). Second in line are PTV Home and Geo News with approximately 8 million average daily Cable and Satellite Viewers. The channel list below provides list of other channels who come in the top 20 channels list. Please note that the figures released are not counting the viewership of Terrestrial TV Viewers. These terrestrial TV viewers still occupy a majority of TV viewers in the country. Data Source: Gallup Pakistan Top 20 channels in terms of viewership in 2013 Target Audience: Cable & Satellite Viewers Period: Jan-Jun , 2013 Function: Daily Average Reach (in % and thousands Viewers) Rank Channel Name Avg Reach % Avg Reach '000 1 Star Plus 17.645 12,507 2 GEO News 11.434 8,105 3 PTV Home 10.544 7,474 4 Sony 8.925 6,327 5 Cartoon Network 8.543 6,055 6 GEO Entertainment 7.376 5,228 7 ARY Digital 5.078 3,599 8 KTN 5 3,544 9 PTV News 4.825 3,420 10 Urdu 1 4.233 3,000 11 Hum TV 4.19 2,970 12 ATV 3.898 2,763 13 Express News 2.972 2,107 14 ARY News 2.881 2,042 15 Ten Sports 2.861 2,028 16 Sindh TV 2.446 1,734 17 PTV Sports 2.213 1,568 18 ARY Qtv 2.019 1,431 19 Samaa TV 1.906 1,351 20 A Plus 1.889 1,339 Gallup Pakistan's TV Ratings service is based on a panel of over 5000 Households Spread across both Urban and Rural areas of Pakistan (covering all four provinces). -

The Gainesville Iguana September 2012 Vol

The Gainesville Iguana September 2012 Vol. 26, Issue 9 Security Overkill in Tampa at RNC Protesters at the Republican National Convention in Tampa on Aug. 27-30 were met by a militarized city. Chants addressed issues head-on: “This is what $50 million dollars looks like!”* and “Take off that riot gear, there ain’t no riot here!” Protests were peaceful and diminished in size by a hurricane threat that canceled buses from around the country. Despite the police's overwhelming numbers and equipment, relations were largely cordial; one activist reported cops clapping along as marchers sang “Solidarity Forever.” Participants who attended the protests will give a report-back at the Civic Media Cen- ter on Wednesday, Sept. 12 at 7 p.m. Photo courtesy of Rob Shaw. * $50 million is the price tag for this authoritarian overkill, with another $50 million spent for the Democratic Convention in Charlotte Sept. 4-6. Noam Chomsky: Too big to fail INSIDE ... Publisher's Note ..............3 The following is the conclusion of an recovered from the devastation of the Civic Media Center Events ......9 article by Noam Chomsky from Tom- war and decolonization took its ago- Dispatch.com and reprinted by Com- nizing course. By the early 1970s, the Directory ................ 10-11 monDreams.org on Aug. 13. The entire U.S. share of global wealth had de- Monthly Event Calendar ....12-13 article is highly recommended with a lot clined to about 25 percent, and the Ask Mr. Econ ................14 of historical background, but space only industrial world had become tripo- General Election Information ...16 allowed the last third to be run. -

Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019

Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019 Coercive Censorship, Muted Dissent: Pakistan Descends into Silence Annual Review of Legislative, Legal and Judicial Developments on Freedom of Expression, Right to Information and Digital Rights in Pakistan Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019 This report was voluntarily produced by the Institute for Research, Advocacy and Development (IRADA), an Islamabad-based independent research and advocacy organization focusing on social development and civil liberties, with the contribution of Faiza Hassan as research assistant and Muhammad Aftab Alam and Adnan Rehmat as lead researchers. Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 1 Attempts to Radicalize Media Regulatory Framework ....................................... 3 Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority (PMRA) .........................................................................3 Media Tribunals ...................................................................................................................................4 i Journalistic and Media Freedoms ........................................................................ 6 Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019 Media Legal Pakistan Murders of Journalists ......................................................................................................................6 Serious Incidents of Harassment and Attacks on Journalists and Media .......................7 Criminal Cases Against Journalists ...............................................................................................8 -

Imran Aslam Is a Senior Journalist from Pakistan and in Currently The

Imran Aslam is a senior journalist from Pakistan and in currently the president of GEO TV Network, where he oversees content for GEO News, GEO Entertainment, Aag (a youth channel) and GEO Super (Sports). Aslam was born in Madras and had his early schooling in Chittagong and Dacca in then East Pakistan. He graduated from Government College, Lahore. He subsequently studied at the London School of Economics (LSE) and School of Oriental & African Studies where he read Economics, Politics, and International Relations. He left Pakistan after a brief incarceration during which he suffered a period in solitary confinement and was subjected to torture in Baluchistan. At that time he was working on a dissertation on the political evolution of Baluchistan. Aslam moved to the United Arab Emirates and worked as the Director of the Royal Flight of Shaikh Zayed Bin Sultan‐Al‐ Nahyan, where he was tasked to single handedly set up a fleet of luxury aircraft for the personal use of the President of the UAE. This is what he describes as the “Arabian Nightmare” of his life. The job enabled him to travel extensively and meet with some exciting political passengers. He woke up one morning from this unreal job and moved back to Pakistan to pursue a career in Journalism. In 1983 Aslam became the Editor of the Star, an evening newspaper that was to blaze a trail in investigative journalism during the days of General Zia‐ul‐Haq. Working with a wonderful team described as “typewriter guerillas” the Star was the samizdat of Pakistan journalism in those oppressive days. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THIS COULD ONLY BE HAPPENING HERE: PLACE AND IDENTITY IN GAINESVILLE’S ZINE COMMUNITY By FIONA E STEWART-TAYLOR A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Fiona E. Stewart-Taylor To the Civic Media Center and all the people in it ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank, first, my committee, Dr. Margaret Galvan and Dr. Anastasia Ulanowicz. Dr. Galvan has been a critical reader, engaged teacher, and generous with her expertise, feedback, reading lists, and time. This thesis has very much developed out of discussions with her about the state of the field, the interventions possible, and her many insights into how and why to write about zines in an academic context have guided and shaped this project from the start. Dr. Ulanowicz is also a generous listener and a valuable reader, and her willingness to enter this committee at a late stage in the project was deeply kind. I would also like to thank Milo and Chris at the Queer Zine Archive Project for an incredible residency during which, reading Minneapolis zines reviewing drag revues, I began to articulate some of my ideas about the importance of zines to build community in physical space, zines as living interventions into community as well as archival memory. Chris and Milo were unfailingly welcoming, friendly, and generous with their time, expertise, and long memories, as well as their vegan sloppy joes. QZAP remains an inspiration for my own work with the Civic Media Center.