Download (1MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Gallup TV Ratings Services – the Only National TV Ratings Service

Gallup TV Ratings Services – The Only National TV Ratings Service Star Plus is Pakistan's Most watched Channel among Cable & Satellite Viewers : Gallup TV Ratings Service Dear Readers, Greetings! Gallup TV Ratings Service (the only National TV Ratings Service) released a report on most popular TV Channels in Pakistan. The report is compiled on the basis of the Gallup TV Ratings Services, the only National TV Ratings available for Pakistan. According to the report, Star Plus tops the list and had an average daily reach of around 12 million Cable and Satellite Viewers during the time period Jan- to date (2013). Second in line are PTV Home and Geo News with approximately 8 million average daily Cable and Satellite Viewers. The channel list below provides list of other channels who come in the top 20 channels list. Please note that the figures released are not counting the viewership of Terrestrial TV Viewers. These terrestrial TV viewers still occupy a majority of TV viewers in the country. Data Source: Gallup Pakistan Top 20 channels in terms of viewership in 2013 Target Audience: Cable & Satellite Viewers Period: Jan-Jun , 2013 Function: Daily Average Reach (in % and thousands Viewers) Rank Channel Name Avg Reach % Avg Reach '000 1 Star Plus 17.645 12,507 2 GEO News 11.434 8,105 3 PTV Home 10.544 7,474 4 Sony 8.925 6,327 5 Cartoon Network 8.543 6,055 6 GEO Entertainment 7.376 5,228 7 ARY Digital 5.078 3,599 8 KTN 5 3,544 9 PTV News 4.825 3,420 10 Urdu 1 4.233 3,000 11 Hum TV 4.19 2,970 12 ATV 3.898 2,763 13 Express News 2.972 2,107 14 ARY News 2.881 2,042 15 Ten Sports 2.861 2,028 16 Sindh TV 2.446 1,734 17 PTV Sports 2.213 1,568 18 ARY Qtv 2.019 1,431 19 Samaa TV 1.906 1,351 20 A Plus 1.889 1,339 Gallup Pakistan's TV Ratings service is based on a panel of over 5000 Households Spread across both Urban and Rural areas of Pakistan (covering all four provinces). -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Asia

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia & Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Herzegonia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Egypt, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Moldova, Montenegro, The Netherlands, Norway, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia. Armenia, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen. Asia & Pacific North & South America Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, United Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Maldives, Myanmar, States of America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan, Phillipines, South Korea, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela. Uzbekistan, Vietnam. Australia, French Polynesia, New Zealand. EUROPE Albania Austria Belarus Belgium Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic France Germany Gibraltar Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy -

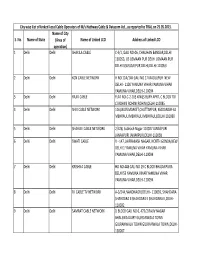

City Wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/S Hathway Cable & Datacom Ltd., As Reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015

City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s Hathway Cable & Datacom Ltd., as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. Name of City S. No. Name of State (Area of Name of Linked LCO Address of Linked LCO operation) 1 Delhi Delhi SHAKILA CABLE C‐9/1, GALI NO‐06, CHAUHAN BANGAR,DELHI 110053, US USMAAN PUR DELHI USMAAN PUR DELHI USMAAN PUR DELHI,DELHI‐110053 2 Delhi Delhi KCN CABLE NETWORK H NO 12A/14K GALI NO 17 MAOUJPUR NEW DELHI ‐ 1100 YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR,DELHI‐110094 3 Delhi Delhi RAJIV CABLE FLAT NO‐C‐2‐103 KINGS BURY APRT, C BLOCK TDI CI ROHINI ROHINI ROHINI,DELHI‐110085 4 Delhi Delhi SHIV CABLE NETWORK 116,MAIN MARKET,CHATTARPUR, MADANGIR‐62 MEHRAULI MEHRAULI MEHRAULI,DELHI‐110030 5 Delhi Delhi SHAHJEE CABLE NETWORK 2/428, Subhash Nagar‐110027 JANAKPURI JANAKPURI JANAKPURI,DELHI‐110058 6 Delhi Delhi SWATI CABLE V ‐ 147, JAIPRAKASH NAGAR, NORTH GONDA,NEW DELHI 1 YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR,DELHI‐110094 7 Delhi Delhi KRISHNA CABLE HO NO 448 GALI NO 19 C BLOCK BHAJANPURA DELHI 53 YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR,DELHI‐110094 8 Delhi Delhi R I CABLE TV NETWORK A‐3/244,NANDNAGRI,DELHI ‐ 110093, SHAHDARA SHAHDARA II SHAHDARA II SHAHDARA II,DELHI‐ 110032 9 Delhi Delhi SAMRAT CABLE NETWORK D BLOCK GALI NO 6, 473/2 RAJIV NAGAR BHALSWA DAIRY GUJRANWALA TOWN GUJRANWALA TOWN GUJRANWALA TOWN,DELHI‐ 110007 City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s Hathway Cable & Datacom Ltd., as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. -

Arabic Global 59

ARABIC GLOBAL 59. AL HAYAT CINEMA 120. BAHRAIN SPORT 1 180. AL RASHEED 60. AL NAHAR TV 121. BAHRAIN SPORT 2 181. AL GHADEER 1. AL JAZEERA ARABIC 61. AL HAYAT SPORT 122. BAHRAIN 55 182. AL QETHARA 2. AL JAZEERA ENGLISH 62. AL HAYAT MUSLSALAT 123. BAHRAIN TV 183. OMANN SPORT 3. AL JAZEERA MASR 63. AL HAYAT SERIES 124. ORIENT 184. ALMERGAB 2 4. AL JAZEERA MUBASHER 64. IMAGINE MOVIES 125. AGHAPY 185. TUNISIA TV 5. MBC 1 65. RUSSIA AL YAUM 126. DUBAI TV 186. TUNISIE TELEVISION 6. MBC WANASAH 66. DW TV ARABIC 127. MAEEN 187. MISRATA 7. MBC 4 67. EURO NEWS ARABIC 128. HAMASAT 188. OMAN TV 8. MBC ACTION 68. FUTURE INTERNATIONAL 129. MADANI 189. OMAN TV2 9. MBC MAX 69. FUTURE USA 130. MTV LEBANON 190. SAWSAN TV 10. MBC DRAMA 70. SYRIA SATELLITE 131. NOURSAT AL SHABAB 191. LIBYA AL HURRA 11. MBC MAGHREB 71. CNBC ARABIYAH 132. AL MASRAWIA 192. TOP MOVIES TV 12. MBC 3 72. MBC MASR 133. ABU DHABI DRAMA 2 193. AL HAQEQA 13. MBC PERSIA 73. PANORAMA DRAMA 2 134. AL ANWAR 194. ALL TV 14. MBC 2 74. CRT DRAMA 135. AL MANAR 195. AL LUBNANIA 15. ROTANA CINEMA 75. PANORAMA FILM 136. AL EKHBARIA 196. TAWAZON 16. ROTANA KHALIJIAH 76. PANORAMA DRAMA 137. CORAN TV 197. KIRKUK TV 17. ROTANA MUSIC 77. AL ARABIYAH AL HADATH 138. TELE LIBAN 198. AL FATH 18. ROTANA CLIP 78. AL ALARABIYA 139. AL YAWM PALESTINE 199. FM TV 19. ROTANA MASRIYA 79. FADAK TV 140. BEDAYA 200. -

§3008. Ordinances Relating to Cable Television Systems §3008

MRS Title 30-A, §3008. ORDINANCES RELATING TO CABLE TELEVISION SYSTEMS §3008. Ordinances relating to cable television systems 1. State policy. It is the policy of this State, with respect to cable television systems: A. To affirm the importance of municipal control of franchising and regulation in order to ensure that the needs and interests of local citizens are adequately met; [PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. A, §2 (NEW); PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. C, §106 (NEW); PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §§8, 10 (AMD).] B. That each municipality, when acting to displace competition with regulation of cable television systems, shall proceed according to the judgment of the municipal officers as to the type and degree of regulatory activity considered to be in the best interests of its citizens; [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (AMD).] C. To provide adequate statutory authority to municipalities to make franchising and regulatory decisions to implement this policy and to avoid the costs and uncertainty of lawsuits challenging that authority; and [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (AMD).] D. To ensure that all cable television operators receive the same treatment with respect to franchising and regulatory processes and to encourage new providers to provide competitive pressure on the pricing of such services. [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (NEW).] [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (AMD).] 1-A. Definitions. For purposes of this section, unless the context otherwise indicates, the following terms have the following meanings: A. "Cable system operator" has the same meaning as "cable operator," as that term is defined in 47 United States Code, Section 522(5), as in effect on January 1, 2008; [PL 2007, c. -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

Media Coverage for Development of Agriculture Sector: an Analytical Study of Television Channels in Pakistan

Media coverage for development of agricultural sector: An analytical study 555 MEDIA COVERAGE FOR DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE SECTOR: AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF TELEVISION CHANNELS IN PAKISTAN Anjum Zia* and Ayesha Khan** ABSTRACT Agriculture sector is considered to be the bedrock of Pakistan’s economy as it plays an important role, directly as well as indirectly, in generating economic and industrial growth. In-spite of such a great significance, the speed of agricultural development in Pakistan is very low. Agricultural production can be increased considerably if available modern production technologies are adopted by the farming community. Media is considered to be one of the best tools to create awareness about the effectiveness and application of new technologies. So the present study was conducted in the Department of Mass Communication, Lahore College for Women, Lahore, Pakistan during the year 2011 to determine extent of television coverage for development of agriculture sector in Pakistan for the period 2006-2010. Data were collected from media practitioners of private and public television channels by applying intensive interview technique. The study concludes that there is only one dedicated television channel (Sohni Dharti) for agriculture sector out of 82 channels. Indeed, a single agricultural channel is inadequate for an agrarian country having 67 percent of total population living in rural areas and 44.7 percent of them connected to farming. The data further indicate that no other television channel was giving due coverage to third largest sector of the economy. However, these television channels were found occasionally accommodating agricultural news items/news packages in their current affair programmes and news bulletins.