Gender-Based Violence Information Management System (GBVIMS) Annual Report 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting Social Cohesion, More Equitable Gender Roles and Local Economic Development in Contexts of Flight and Migration

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Loewe, Markus et al. Research Report Community effects of cash-for-work programmes in Jordan: Supporting social cohesion, more equitable gender roles and local economic development in contexts of flight and migration Studies, No. 103 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Loewe, Markus et al. (2020) : Community effects of cash-for-work programmes in Jordan: Supporting social cohesion, more equitable gender roles and local economic development in contexts of flight and migration, Studies, No. 103, ISBN 978-3-96021-135-8, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/s103.2020 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/227755 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities Key Informant Interviews / District Profiling January 2014 This project has been implemented with the support of: Syrian Refugees in Host Communities: Key Informant Interviews and District Profiling January 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the Syrian crisis extends into its third year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan continues to increase with the vast majority living in host communities outside of planned camps.1 This assessment was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of issues related to sector specific and municipal services. In total, 1,445 in-depth interviews were conducted in September and October 2013 with key informants who were identified as knowledgeable about the 446 surveyed communities. The information collected is disaggregated by key characteristics including access to essential services by Syrian refugees, and underlying factors such as the type and location of their shelters. This project was carried out to inform more effective humanitarian planning and interventions which target the needs of Syrian refugees in Jordanian host communities. The study provides a multi-sector profile for the 19 districts of northern Jordan where the majority of Syrian refugees reside2, focusing on access to municipal and other essential services by Syrian refugees, including primary access to basic services; barriers to accessing social services; trends over time; and the prioritised needs of refugees by sector. The project is funded by the British Embassy of Amman with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The greatest challenge faced by Syrian refugees is access to cash, specifically cash for rent, followed by access to food assistance and non-food items for the winter season. -

Women's Political Participation in Jordan

MENA - OECD Governance Programme WOMEN’S Political Participation in JORDAN © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 2 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN JORDAN: BARRIERS, OPPORTUNITIES AND GENDER SENSITIVITY OF SELECT POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS MENA - OECD Governance Programme © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 3 OECD The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. It is an international organization made up of 37 member countries, headquartered in Paris. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems within regular policy dialogue and through 250+ specialized committees, working groups and expert forums. The OECD collaborates with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change and sets international standards on a wide range of things, from corruption to environment to gender equality. Drawing on facts and real-life experience, the OECD recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people’s. MENA - OECD MENA-OCED Governance Programme The MENA-OECD Governance Programme is a strategic partnership between MENA and OECD countries to share knowledge and expertise, with a view of disseminating standards and principles of good governance that support the ongoing process of reform in the MENA region. The Programme strengthens collaboration with the most relevant multilateral initiatives currently underway in the region. In particular, the Programme supports the implementation of the G7 Deauville Partnership and assists governments in meeting the eligibility criteria to become a member of the Open Government Partnership. -

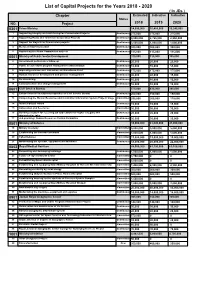

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2018 2019 2020 0301 Prime Ministry 14,090,000 10,455,000 10,240,000 1 Supporting Integrity and Anti-Corruption Commission Projects Continuous 275,000 275,000 275,000 2 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 9,900,000 8,765,000 8,550,000 3 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 4 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 5 Supporting the Media Commission projects Continuous 115,000 115,000 115,000 0501 Ministry of Public Sector Development 310,000 310,000 305,000 6 Government performance follow up Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 7 Public sector reform program management administration Continuous 55,000 55,000 55,000 8 Improving services and Innovation and Excellence Fund Continuous 175,000 175,000 175,000 9 Human resources development and policies management Continuous 40,000 40,000 35,000 10 Re-structuring Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 11 Communication and change management Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 0601 Civil Service Bureau 575,000 435,000 345,000 12 Enhancement of institutional capacities of Civil Service Bureau Continuous 200,000 150,000 150,000 13 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Project/ Stage Committed 290,000 200,000 110,000 2 14 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 15 Automation and E-services Committed 30,000 30,000 30,000 16 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 administrative jobs. -

JICA's Cooperation for Water Sector in Jordan

JICA’s Cooperation for Water Sector in Jordan 30 years history of remarkable achievements 1 | P a g e Message from Chief Representative of JICA Jordan Mr. TANAKA Toshiaki Japanese ODA to Jordan started much earlier than the establishment of JICA office. The first ODA loan to Jordan was provided in 1974, the same year when Embassy of Japan in Jordan was established. The first technical cooperation project started in 1977, though technical cooperation to Jordan may have started earlier, and the first grant aid to Jordan was provided in 1979. Since then, the Government of Japan has provided Jordan with total amount of more than 200 billion Japanese yen as ODA loan, more than 60 billion yen as Grant aid and nearly 30 billion yen as technical cooperation. In 1985, two agreements between the two countries on JICA activities were concluded. One is the technical cooperation agreement and the other is the agreement on Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers. On the basis of the agreement, JICA started JOCV program in Jordan and established JOCV coordination office which was followed by the establishment of JICA Jordan office. For the promotion of South-South Cooperation in the region, Japan-Jordan Partnership Program was agreed in 2004, furthering Jordan’s position as a donor country and entering a new stage of relationship between the two countries. In 2006, Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) inaugurated Amman office, which was integrated with JICA Jordan office in 2008 when new JICA was established as a result of a merger of JICA with ODA loan operation of JBIC. -

THE STARTUP GUIDE Business in Jordan

Your complete guide to registering and licensing a small THE STARTUP GUIDE business in Jordan Find out what to do, where to go and what fees are required to formalize your small business in this simple, step-by-step guide Contents WHY SHOULD I REGISTER AND LICENSE MY BUSINESS? ........................................................................................ 2 WHAT ARE THE STEPS I NEED TO TAKE IN ORDER TO FORMALIZE MY BUSINESS? ............................................... 3 HOW DO I KNOW WHAT TYPE OF BUSINESS TO REGISTER? ................................................................................. 4 HOW DO I CHOOSE A BUSINESS STRUCTURE THAT’S RIGHT FOR ME? ................................................................. 6 I’VE CHOSEN MY BUSINESS STRUCTURE… WHAT NEXT? ...................................................................................... 8 I’VE GOTTEN MY PRE-APPROVALS. HOW DO I REGISTER MY BUSINESS? ............................................................. 9 A) REGISTERING AN INDIVIDUAL ESTABLISHMENT ........................................................................................ 10 B) REGISTERING A GENERAL PARTNERSHIP OR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP COMPANY ...................................... 13 C) REGISTERING A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY ........................................................................................... 16 D) REGISTERING A PRIVATE SHAREHOLDING COMPANY................................................................................ 20 I’VE REGISTERED MY BUSINESS. HOW CAN I SET -

Jordan Ministry of Environment

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Ministry of Environment The Fifth National Report on the Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity September 2014 In cooperation with and support from: Publisher Jor danian Ministry of Environment (MoEnv) In cooperation with the Global Environmental Facility and The World Bank Author International Union for the Conservation of Nature – Regional Office for West Asia (IUCN-ROWA) Citation 2014: Jordanian Fifth National Report on the Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Ministry of Environment, Amman, Jordan. 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 5 Part I: Biodiversity Status, Trends and Threats ..................................................................................... 10 Section 1: The Importance of Biodiversity for Jordan .........................................................................10 1:1 Jordan Country Profile ..................................................................................................................10 1:2 Overview of Jordan’s Biodiversity ................................................................................................12 -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Diasporic Urbanism: Place, Politics and Development in a Jordanian-Palestinian Neighbourhood PRICE, MARTIN,WILLIAM,HENRY How to cite: PRICE, MARTIN,WILLIAM,HENRY (2020) Diasporic Urbanism: Place, Politics and Development in a Jordanian-Palestinian Neighbourhood, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13550/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Diasporic Urbanism Place, Politics and Development in a Jordanian- Palestinian Neighbourhood Martin Price Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography, Durham University January 2020 2 Abstract This research presents ‘diasporic urbanism’ as a framework capable of interrogating the ways in which place and locality feature in the lives of diasporic communities. The objective of diasporic urbanism is not to provide a renewed, prescriptive account of what ‘diaspora’ and ‘the diasporic’ entail. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Improvement of Waste Management Equipment in Northern Region Hosting Syrian Refugees in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

Ministry of Municipal Affairs (MOMA) The Hashemite Kingdome of Jordan PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR IMPROVEMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT EQUIPMENT IN NORTHERN REGION HOSTING SYRIAN REFUGEES IN THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN OCTOBER 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. GE JR 17-115 The exchange rate used in this report is as follows US$ 1.0 = 115.63 Yen, 1 EURO = 123.08 Yen, 1 JD = 162.58 Yen (Average rate of three months from Dec 2016, Jan and Feb 2017) Summary 1. Outline of the Country (1) Land and Nature Jordan, formally known as the Hashemite Kingdome of Jordan, has an area of about 89,000 km2, surrounded by Syria on the north and Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Israel in a clockwise order. Its coastline is only 15 km on the south end facing the Gulf of Aqaba. The Jordan Valley, which forms the northern tip of the African Great Rift Valley, runs in the west of the country from south to north and is famous for the world’s lowest elevation at 200 to 400 meters below sea level. Being warm in winter and hot in summer, the area is prosperous in irrigated agriculture. To the east are hilly plateaus of Mediterranean climate with some peaks over 1,500 m high. In the hilly plateaus in winter, sometimes there is snowfall that makes the passage of vehicles difficult. Further to the east is desert, which covers as much as 80% of the country. Its southeast part is extremely dry as the yearly rainfall can be less than 35 mm. -

Assessment Report June 2014 Understanding Social Cohesion & Resilience in Jordanian Host Communities – April 2014

UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL COHESION AND RESILIENCE IN JORDANIAN HOST COMMUNITIES Assessment Report June 2014 Understanding Social Cohesion & Resilience in Jordanian Host Communities – April 2014 SUMMARY The Syrian crisis, now in its fourth year, has led to the displacement of 9.3 million people. Although most are currently considered internally displaced within Syria, approximately 2.6 million refugees have crossed borders into neighbouring countries in the region. Jordan is currently hosting 588,979 refugees, of which an estimated 80% live in host communities. This large influx of Syrian refugees has led to an overstretching of the absorptive capacity of Jordanian communities and as the population grows, service delivery deteriorates and the competition for resources intensifies particularly in northern Jordan. This situation was well highlighted in the Needs Assessment Review (NAR) of the Impact of the Syrian Crisis on Jordan released in November 2013. The response by the Government of Jordan (GoJ) in coordination with the United Nations and international organisations has been to establish in Septembre 2013 the Host Community Support Platform (HCSP) for improving access to services, strengthening social cohesion and building resilience, as well as to develop a National Resilience Plan (NRP) for the period 2014 – 2016. The plan aims to coordinate the development response and is structured around the various social services and economic characteristics that are often referred to by government and aid actors as key sectors: water, employment and livelihoods, health, education, and municipal support. The analysis within this report is also disaggregated into these sectors – including as well access to shelter and affordable housing that has emerged as a key challenge on community level. -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Jordan India Fertilizer

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Jordan India Fertilizer Company (JIFCO) Volume (I) MAIN REPORT Submitted to: Jordan Phosphate Mines Company (JPMC) Submitted by: Royal Scientific Society / Environmental Research Centre Prepared by: Mohammad Mosa (Project Manager) Salah Abu-Salah Najeeb Al-Atiyat Jehan Hadad Rawia Abdalla Nuwar Al-Husseini Faysal Anani Supervised by: Dr. Bassam Hayek (Director of ERC) June, 2008 This document is a property of Jordan India Fertilizer Company (JIFCO) and the Royal Scientific Society (RSS). No part of this document may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means or stored in a database or retrieval system without the prior permission from both JIFCO and RSS including but not limited to in any network or other electronic storage or transmission. However, the document shall be used by JIFCO for fulfilling the requirements of the project. So, the document will be used by tenders and the regularity authorities in Jordan as and when required. ESIA/JIFCO Project ii Study Team The Environmental Research Centre (ERC) has been providing specialized technical studies and services since 1989 in a number of environmental areas. ERC has a specialized staff in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA), it has conducted comprehensive ESIA studies for various major development projects. The environmental and social impact assessment study of the project was led by the Environmental Research Centre of the Royal Scientific Society (RSS). The biodiversity study, the archeological survey and the marine environment study were conducted by external consultants hired by RSS. The following is a list of contributors to this study. -

Governorates Budgets According to the Determined Ceiling

Total of Capital Expenditures Distributed According to the Determined Ceilings for the Fiscal Year 2018 ( In JDs ) Expenditures of GOVERNORATE Sustaining the Capital Total Work of the Expenditures Governorates Councils Irbid Governorate 372,000 22,981,000 23,353,000 Mafraq Governorate 325,000 18,952,000 19,277,000 Jerash Governorate 176,000 14,974,000 15,150,000 Ajloun Governorate 189,000 15,818,000 16,007,000 The Capital Governorate 474,000 34,464,000 34,938,000 Balqa' Governorate 216,000 16,400,000 16,616,000 Zarqa Governorate 284,000 20,322,000 20,606,000 Ma'daba Governorate 162,000 13,691,000 13,853,000 Karak Governorate 230,000 14,361,000 14,591,000 Ma'an Governorate 162,000 19,121,000 19,283,000 Tafileh Governorate 155,000 13,785,000 13,940,000 Aqaba Governorate 155,000 15,131,000 15,286,000 Total 2,900,000 220,000,000 222,900,000 Budget Summary of Irbid Governorate for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs) Description Estimated Indicative Indicative 2018 2019 2020 Expenditures of Sustaining the Work of the Governorate Council 372,000 385,000 385,000 Capital Expendituers 22,981,000 23,967,000 25,733,000 Total 23,353,000 24,352,000 26,118,000 Appropriations of Sustaining the Council Work of Irbid Governorate for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs) Description Estimated Indicative Indicative 2018 2019 2020 001 Council of Irbid Governorate 372,000 385,000 385,000 001 Bonuses 312,000 312,000 312,000 004 Hospitality 3,900 3,900 3,900 999 Others 56,100 69,100 69,100 Total 372,000 385,000 385,000 Capital Budget for Irbid Governorate for the years