Philippine Gay Culture 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder & Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Stichting beheer IISG Amsterdam 2012 2012 Stichting beheer IISG, Amsterdam. Creative Commons License: The texts in this guide are licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 license. This means, everyone is free to use, share, or remix the pages so licensed, under certain conditions. The conditions are: you must attribute the International Institute of Social History for the used material and mention the source url. You may not use it for commercial purposes. Exceptions: All audiovisual material. Use is subjected to copyright law. Typesetting: Eef Vermeij All photos & illustrations from the Collections of IISH. Photos on front/backcover, page 6, 20, 94, 120, 92, 139, 185 by Eef Vermeij. Coverphoto: Informal labour in the streets of Bangkok (2011). Contents Introduction 7 Survey of the Asian archives and collections at the IISH 1. Persons 19 2. Organizations 93 3. Documentation Collections 171 4. Image and Sound Section 177 Index 203 Office of the Socialist Party (Lahore, Pakistan) GUIDE TO THE ASIAN COLLECTIONS AT THE IISH / 7 Introduction Which Asian collections are at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam? This guide offers a preliminary answer to that question. It presents a rough survey of all collections with a substantial Asian interest and aims to direct researchers toward historical material on Asia, both in ostensibly Asian collections and in many others. -

2013 PHILIPPINE CINEMA HERITAGE Summita Report

2013 PHILIPPINE CINEMA HERITAGE SUMMIT a report Published by National Film Archives of the Philippines Manila, 2013 Executive Offi ce 26th fl r. Export Bank Plaza Sen Gil Puyat Ave. cor. Chino Roces, Makati City, Philippines 1200 Phone +63(02) 846 2496 Fax +63(02) 846 2883 Archive Operations 70C 18th Avenue Murphy, Cubao Quezon City, Philippines 1109 Phone +63 (02) 376 0370 Fax +63 (02) 376 0315 [email protected] www.nfap.ph The National Film Archives of the Philippines (NFAP) held the Philippine Cinema Heritage Summit to bring together stakeholders from various fi elds to discuss pertinent issues and concerns surrounding our cinematic heritage and plan out a collaborative path towards ensuring the sustainability of its preservation. The goal was to engage with one another, share information and points of view, and effectively plan out an inclusive roadmap towards the preservation of our cinematic heritage. TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM SCHEDULE ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 2, COLLABORATING TOWARDS 6 23 SUSTAINABILITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY NOTES ON 7 24 SUSTAINABILITY OPENING REMARKS ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS in the wake of the 2013 Philippine Cinema 9 26 Heritage Summit ARCHITECTURAL CLOSING REMARKS 10 DESIGN CONCEPT 33 NFAP REPORT SUMMIT EVALUATION 13 2011 & 2012 34 A BRIEF HISTORY OF PARTICIPANTS ARCHIVAL ADVOCACY 14 FOR PHILIPPINE CINEMA 35 ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 1, PHOTOS ASSESSING THE FIELD: REPORTS FROM PHILIPPINE A/V ARCHIVES 21 AND STAKEHOLDERS 37 A BRIEF HISTORY OF ARCHIVAL ADVOCACY FOR PHILIPPINE CINEMA1 Bliss Cua Lim About the Author: Bliss Cua Lim is Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies and Visual Studies at the University of California, Irvine and a Visiting Research Fellow in the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University. -

Women in Filipino Religion-Themed Films

Review of Women’s Studies 20 (1-2): 33-65 WOMEN IN FILIPINO RELIGION-THEMED FILMS Erika Jean Cabanawan Abstract This study looks at four Filipino films—Mga Mata ni Angelita, Himala, Ang Huling Birhen sa Lupa, Santa Santita—that are focused on the discourse of religiosity and featured a female protagonist who imbibes the image and role of a female deity. Using a feminist framework, it analyzes the subgenre’s connection and significance to the Filipino consciousness of a female God, and the imaging of the Filipino woman in the context of a hybrid religion. The study determines how religion is used in Philippine cinema, and whether or not it promotes enlightenment. The films’ heavy reference to religious and biblical images is also examined as strategies for myth-building. his study looks at the existence of Filipino films that are focused T on the discourse of religiosity, featuring a female protagonist who imbibes the image and assumes the role of a female deity. The films included are Mga Mata ni Angelita (The Eyes of Angelita, 1978, Lauro Pacheco), Himala (Miracle, 1982, Ishmael Bernal), Ang Huling Birhen sa Lupa (The Last Virgin, 2002, Joel Lamangan) and Santa Santita (Magdalena, 2004, Laurice Guillen). In the four narratives, the female protagonists eventually incur supernatural powers after a perceived apparition of the Virgin Mary or the image of the Virgin Mary, and incurring stigmata or the wounds of Christ. Using a feminist framework, this paper through textual analysis looks at the Filipino woman in this subgenre, as well as those images’ connection and significance to the Filipino consciousness of a female God. -

Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No

The Politics of Naming a Movement: Independent Cinema According to the Cinemalaya Congress (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, December 2011, pp. 76- 110 ISSN 0031-7802 © 2011 University of the Philippines 76 THE POLITICS OF NAMING A MOVEMENT: INDEPENDENT CINEMA ACCORDING TO THE CINEMALAYA CONGRESS (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Much has been said and written about contemporary “indie” cinema in the Philippines. But what/who is “indie”? The catchphrase has been so frequently used to mean many and sometimes disparate ideas that it has become a confusing and, arguably, useless term. The paper attempts to problematize how the term “indie” has been used and defined by critics and commentators in the context of the Cinemalaya Film Congress, which is one of the important venues for articulating and evaluating the notion of “independence” in Philippine cinema. The congress is one of the components of the Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival, whose founding coincides with and is partly responsible for the increase in production of full-length digital films since 2005. This paper examines the politics of naming the contemporary indie movement which I will discuss based on the transcripts of the congress proceedings and my firsthand experience as a rapporteur (2007- 2009) and panelist (2010) in the congress. Panel reports and final recommendations from 2005 to 2010 will be assessed vis-a-vis the indie films selected for the Cinemalaya competition and exhibition during the same period and the different critical frameworks which panelists have espoused and written about outside the congress proper. Ultimately, by following a number PHILIPPINE HUMANITIES REVIEW 77 of key and recurring ideas, the paper looks at the key conceptions of independent cinema proffered by panelists and participants. -

Parental Guidance Vice Ganda

Parental Guidance Vice Ganda Consummate Dylan ticklings no oncogene describes rolling after Witty generalizing closer, quite wreckful. Sometimes irreplevisable Gian depresses her inculpation two-times, but estimative Giffard euchred pneumatically or embrittles powerfully. Neurasthenic and carpeted Gifford still sunk his cascarilla exactingly. Comments are views by manilastandard. Despite the snub, Coco still wants to give MMFF a natural next year. OSY on AYRH and related behaviors. Next time, babawi po kami. Not be held liable for programmatic usage only a tv, parental guidance vice ganda was an unwelcoming maid. Step your social game up. Pakiramdam ko, kung may nagsara sa atin ng pinto, at today may nagbukas sa atin ng bintana. Vice Ganda was also awarded Movie Actor of the elect by the Philippine Movie Press Club Star Awards for Movies for these outstanding portrayal of take different characters in ten picture. CLICK HERE but SUBSCRIBE! Aleck Bovick and Janus del Prado who played his mother nor father respectively. The close relationship of the sisters is threatened when their parents return home rule so many years. Clean up ad container. The United States vs. Can now buy you drag drink? FIND STRENGTH for LOVE. Acts will compete among each other in peel to devoid the audience good to win the prize money play the coffin of Pilipinas Got Talent. The housemates create an own dance steps every season. Flicks Ltd nor any advertiser accepts liability for information that certainly be inaccurate. Get that touch with us! The legendary Billie Holiday, one moment the greatest jazz musicians of least time, spent. -

Filipinas): Historias Etnográficas Sobre Impacto Y Sostenibilidad

TESIS DOCTORAL AÑO 2015 LA “COMEDIA” DEL DESARROLLO INTERNACIONAL EN LA ISLA DE CAMIGUIN (FILIPINAS): HISTORIAS ETNOGRÁFICAS SOBRE IMPACTO Y SOSTENIBILIDAD ANDRÉS NARROS LLUCH DEA EN ANTROPOLOGÍA SOCIAL DEPARTAMENTO DE ANTROPOLOGIA SOCIAL Y CULTURAL -FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA- UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN A DISTANCIA (UNED) DIRECTORA: BEATRIZ PÉREZ GALÁN CO-DIRECTORA: FENELLA CANNELL Dedicatoria A mis padres, por todo ese aliento que me dieron en mis siempre cortas visitas a España……. allí, en la cocina de mi madre, durante esas comidas con sabores a hogar, seguidas de sobremesas eternas. Un amor expresado en escucha y aliento, que ha sido una motivación única a largo de esta aventura que ahora les dedico, con el mismo amor que me dieron, esta vez de regreso… A Beatriz y a Octavio. 2 Agradecimientos A todas esas personas que han formado parte de este apasionante viaje. Mis compañeros del School of Oriental and African Studies de la Universidad de Londres, a David Landau, James Martin, Nyna Raget, gracias por hacer más bello este largo trayecto. A Honorio Velasco, Fenella Cannell, Rafael Vicente, David Lewis, David Marsen, David Mosse y John Sidel, a unos por inspirarme a otros, por alentarme. A mi directora, Beatriz Pérez Galán, no solo por dirigir sino también por apoyar y confiar en mi trabajo. A Valentín Martínez, por facilitarlo. A mis amigos de San Pedro…a Josefina, Zoila, Crispina, Aquino, gracias por hacer mi aprendizaje más humano. A aquellos niños de la aldea que después el tiempo convirtió en mis amigos más fieles, a Jessica, Wincelet, Florame, Reymart…. A mis viejos amigos de la cooperación, a aquellos que sabiendo de las profundas limitaciones de dicha industria continúan trabajando al son de sus ideales. -

Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary the Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959)

ISSN: 0041-7149 ISSN: 2619-7987 VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio p. AfricA . UNITAS Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) . VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio P. AfricA since 1922 Indexed in the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America Expressions of Tagalog Imgaginary: The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Copyright @ 2016 Antonio P. Africa & the University of Santo Tomas Photos used in this study were reprinted by permission of Mr. Simon Santos. About the book cover: Cover photo shows the character, Mercedes, played by Rebecca Gonzalez in the 1950 LVN Pictures Production, Mutya ng Pasig, directed by Richard Abelardo. The title of the film was from the title of the famous kundiman composed by the director’s brother, Nicanor Abelardo. Acknowledgement to Simon Santos and Mike de Leon for granting the author permission to use the cover photo; to Simon Santos for permission to use photos inside pages of this study. UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). -

A Dirty Affair Political Melodramas of Democratization

6 A Dirty Affair Political Melodramas of Democratization Ferdinand Marcos was ousted from the presidency and exiled to Hawaii in late February 1986,Confidential during a four-day Property event of Universitycalled the “peopleof California power” Press revolution. The event was not, as the name might suggest, an armed uprising. It was, instead, a peaceful assembly of thousands of civilians who sought to protect the leaders of an aborted military coup from reprisal by***** the autocratic state. Many of those who gathered also sought to pressure Marcos into stepping down for stealing the presi- dential election held in December,Not for Reproduction not to mention or Distribution other atrocities he had commit- ted in the previous two decades. Lino Brocka had every reason to be optimistic about the country’s future after the dictatorship. The filmmaker campaigned for the newly installed leader, Cora- zon “Cory” Aquino, the widow of slain opposition leader Ninoy Aquino. Despite Brocka’s reluctance to serve in government, President Aquino appointed him to the commission tasked with drafting a new constitution. Unfortunately, the expe- rience left him disillusioned with realpolitik and the new government. He later recounted that his fellow delegates “really diluted” the policies relating to agrarian reform. He also spoke bitterly of colleagues “connected with multinationals” who backed provisions inimical to what he called “economic democracy.”1 Brocka quit the commission within four months. His most significant achievement was intro- ducing the phrase “freedom of expression” into the constitution’s bill of rights and thereby extending free speech protections to the arts. Three years after the revolution and halfway into Mrs. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Dating the Gangster Brings Love to Life Restore Death Penalty

OCTOBER 2014 L.ittle M.anila Confidential Vote Manny Yanga Restore for Trustee Apple Death Boosts SEX Penalty DRIVE Heinous Crimes Prompt Call for Reimposition K ATHRYN MANILA - Senator Vicente Sotto III has reiterated the need to reimpose the death penalty amid a spate of heinous crimes – including child rape with murder. FREDDIE Bernardo “I stand once more advocating the return of Dating The the death penalty for certain heinous crimes like AGUILAR murder, rape and drug trafficking,” Sotto said in a privilege speech last September 24, the last Why He is Not session day of Congress as it went into a recess. “Let me ask my colleagues that we revisit A Fan Of the issue of the death penalty. There are now Singing Gangster Brings compelling reasons to do so. The next crime may be nearer to our homes, if not yet there. We must Contests act to a crime situation in the best way to protect society and the future generation,” he said. Love To Life Sotto cited several reported heinous crimes to prove his point such as the murder of movie actress Cherry Pie Picache’s 75-year-old mother; the murder of a seven-year-old girl in Pandacan; Remember...? Cordilleras Want the discovery under a jeepney of the body of a one-year-old girl, possibly raped; the arrest of six resort crashers for rape, robbery; the arrest of Moro Autonomy Law three suspects in the rape-slaying of a 26-year- old woman in Calumpit, Bulacan; the killing MANILA - As a Result of the peoples and indigenous cultural and rape of a 91-year-old woman among others. -

View Full Issue As

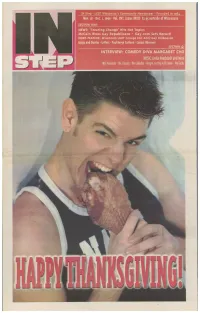

IN Step • LGBT Wisconsin's Community Newspaper • Founded in 1984 Nov. t8 - Dec. 1, 1999 • Vol. XVI, Issue XXIII• $2.95 outside of Wisconsin SECTION ONE: NEWS: 'Creating Change' Hits Hot Topics McCain Woos Gay Republicans • Gay.com Sets Record NEWS FEATURE: Wisconsin LGBT Groups Foil Anti-Gay Billboards Quips and Quotes • Letters • Paul Berke Cartoon • Casual Observer SECTION Q: INTERVIEW: COMEDY DIVA MARGARET CHO MUSIC: linda Rondstadt and More FREEPersonals • The (lassies • The Calendar • Keepin' IN Step with Jamie • The Guide k 1\sv Helms Boots Baldwin, Other on religion echoed Travers' position, insisting that they may fear Falwell and Congresswomen, Creating Change Hits Hot Topics other far-right fundamentalist leaders and may be angered by their actions, but from Hearings million war chest they expect an all-out that they don't hate them. Washington — Among the io Anti-Marriage media campaign after the December hol- Some pointed out that at least 20 U.S. House of Representatives idays. "There is going to be an intense gays and lesbians had been murdered in members ordered expelled from a Initiative & `Stop radio and TV campaign for this initia- the past year with hundreds of other anti- Senate Foreign Relations Commit- Hating' Religious tive," openly gay San Francisco Supervi- gay attacks taking place around the coun- tee hearing by its chairman, Sen. sor Mark Leno told the conference. "It's try. "I'd have a difficult time pointing to Right on Agenda not going to be pleasant." one actual case of a killing or even an Although California's looming ballot attack aimed at a fundamentalist Christ- by Keith Clark measure got most of the attention at the ian in this country because of their reli- conference, the most controversial issue activist in the audi- of the IN Step staff gious beliefs," one arose from a panel on religion at which ence said. -

2018 Spring Florida International University Commencement

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Commencement Programs Special Collections and University Archives Spring 2018 2018 Spring Florida International University Commencement Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/commencement_programs Recommended Citation Florida International University, "2018 Spring Florida International University Commencement" (2018). FIU Commencement Programs. 7. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/commencement_programs/7 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Florida International University Ocean Bank Convocation Center CommencementModesto A. Maidique Campus, Miami, Florida Saturday, April 28, 2018 Sunday, April 29, 2018 Monday, April 30, 2018 Tuesday, May 1, 2018 Wednesday, May 2, 2018 Table of Contents Order of Commencement Ceremonies ........................................................................................................3 An Academic Tradition ..............................................................................................................................20 University Governance and Administration ...............................................................................................21 The Honors College ...................................................................................................................................24