Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2020 Issue

Volume XXXVIII No. 9 September 2020 Montreal, QC www.filipinostar.org Second COVID-19 wave has already stOaTTAWrA,tSepetembder 23:, PM in address to natesttedipoositiven for the virus. 2020 -- Prime Minister Justin Trudeau "This is the time for all of us as says that in some parts of the country Canadians, to do our part for our the COVID-19 second wave has country, as government does its part already begun, but Canadians have for you," he said. the power to flatten the curve again, in Responding to Trudeau’s his evening address to the nation declaration of a second wave, CTV from his West Block office. Infectious Disease Specialist Dr. Abdu "In our four biggest provinces, Sharkawy said that he thinks we’re the second wave isn’t just starting, it’s “very much there.” already underway," said Trudeau, of “We have seen that the the current outbreaks in British numbers are rising disproportionate to Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and the number of tests that are being Quebec. "We’re on the brink of a fall done, and we've seen a consistent that could be much worse than the trend of community transmission that spring." has been uncontrolled now for some COVID-19 cases have jumped time. And it's evidenced by people in nationally, from about 300 cases per my emergency room and in my ICU,” day in mid-August to 1,248 on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivers his address to the nation Dr. Sharkawy said, adding that Tuesday, prompting Chief Public in the evening after the speech from the throne from his West addressing the current testing Health Officer Dr. -

Women in Filipino Religion-Themed Films

Review of Women’s Studies 20 (1-2): 33-65 WOMEN IN FILIPINO RELIGION-THEMED FILMS Erika Jean Cabanawan Abstract This study looks at four Filipino films—Mga Mata ni Angelita, Himala, Ang Huling Birhen sa Lupa, Santa Santita—that are focused on the discourse of religiosity and featured a female protagonist who imbibes the image and role of a female deity. Using a feminist framework, it analyzes the subgenre’s connection and significance to the Filipino consciousness of a female God, and the imaging of the Filipino woman in the context of a hybrid religion. The study determines how religion is used in Philippine cinema, and whether or not it promotes enlightenment. The films’ heavy reference to religious and biblical images is also examined as strategies for myth-building. his study looks at the existence of Filipino films that are focused T on the discourse of religiosity, featuring a female protagonist who imbibes the image and assumes the role of a female deity. The films included are Mga Mata ni Angelita (The Eyes of Angelita, 1978, Lauro Pacheco), Himala (Miracle, 1982, Ishmael Bernal), Ang Huling Birhen sa Lupa (The Last Virgin, 2002, Joel Lamangan) and Santa Santita (Magdalena, 2004, Laurice Guillen). In the four narratives, the female protagonists eventually incur supernatural powers after a perceived apparition of the Virgin Mary or the image of the Virgin Mary, and incurring stigmata or the wounds of Christ. Using a feminist framework, this paper through textual analysis looks at the Filipino woman in this subgenre, as well as those images’ connection and significance to the Filipino consciousness of a female God. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming the Artist, Composing the Philippines: Listening for the Nation in the National Artist Award A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Neal D. Matherne June 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Sally Ann Ness Dr. Jonathan Ritter Dr. Christina Schwenkel Copyright by Neal D. Matherne 2014 The Dissertation of Neal D. Matherne is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This work is the result of four years spent in two countries (the U.S. and the Philippines). A small army of people believed in this project and I am eternally grateful. Thank you to my committee members: Rene Lysloff, Sally Ness, Jonathan Ritter, Christina Schwenkel. It is an honor to receive your expert commentary on my research. And to my mentor and chair, Deborah Wong: although we may see this dissertation as the end of a long journey together, I will forever benefit from your words and your example. You taught me that a scholar is not simply an expert, but a responsible citizen of the university, the community, the nation, and the world. I am truly grateful for your time, patience, and efforts during the application, research, and writing phases of this work. This dissertation would not have been possible without a year-long research grant (2011-2012) from the IIE Graduate Fellowship for International Study with funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I was one of eighty fortunate scholars who received this fellowship after the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Program was cancelled by the U.S. -

Si Judy Ann Santos at Ang Wika Ng Teleserye 344

Sanchez / Si Judy Ann Santos at ang Wika ng Teleserye 344 SI JUDY ANN SANTOS AT ANG WIKA NG TELESERYE Louie Jon A. Sánchez Ateneo de Manila University [email protected] Abstract The actress Judy Ann Santos boasts of an illustrious and sterling career in Philippine show business, and is widely considered the “queen” of the teleserye, the Filipino soap opera. In the manner of Barthes, this paper explores this queenship, so-called, by way of traversing through Santos’ acting history, which may be read as having founded the language, the grammar of the said televisual dramatic genre. The paper will focus, primarily, on her oeuvre of soap operas, and would consequently delve into her other interventions in film, illustrating not only how her career was shaped by the dramatic genre, pre- and post- EDSA Revolution, but also how she actually interrogated and negotiated with what may be deemed demarcations of her own formulation of the genre. In the end, the paper seeks to carry out the task of generically explicating the teleserye by way of Santos’s oeuvre, establishing a sort of authorship through intermedium perpetration, as well as responding on her own so-called “anxiety of influence” with the esteemed actress Nora Aunor. Keywords aura; iconology; ordinariness; rules of assemblage; teleseries About the Author Louie Jon A. Sánchez is the author of two poetry collections in Filipino, At Sa Tahanan ng Alabok (Manila: U of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2010), a finalist in the Madrigal Gonzales Prize for Best First Book, and Kung Saan sa Katawan (Manila: U of Santo To- mas Publishing House, 2013), a finalist in the National Book Awards Best Poetry Book in Filipino category; and a book of creative nonfiction, Pagkahaba-haba Man ng Prusisyon: Mga Pagtatapat at Pahayag ng Pananampalataya (Quezon City: U of the Philippines P, forthcoming). -

Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary the Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959)

ISSN: 0041-7149 ISSN: 2619-7987 VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio p. AfricA . UNITAS Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) . VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio P. AfricA since 1922 Indexed in the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America Expressions of Tagalog Imgaginary: The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Copyright @ 2016 Antonio P. Africa & the University of Santo Tomas Photos used in this study were reprinted by permission of Mr. Simon Santos. About the book cover: Cover photo shows the character, Mercedes, played by Rebecca Gonzalez in the 1950 LVN Pictures Production, Mutya ng Pasig, directed by Richard Abelardo. The title of the film was from the title of the famous kundiman composed by the director’s brother, Nicanor Abelardo. Acknowledgement to Simon Santos and Mike de Leon for granting the author permission to use the cover photo; to Simon Santos for permission to use photos inside pages of this study. UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). -

Sólo Un Milagro Hará Que Gane El

Año 59. No. 19,683 $6.00 Colima, CoIima Viernes 13 de Abril de 2012 www.diariodecolima.com De acuerdo al Observatorio Nacional Ciudadano Aumentan extorsiones, robos violentos y de vehículos En el último cuatrimestre de 2011, en el estado se incrementó la extorsión 150 por ciento, y el robo de vehículos, 24.8 por ciento; hubo 165 homicidios dolosos el año pasado Mario Alberto SOLÍS ESPINOSA En contraparte, los homicidios dolosos decrecieron de 56 a 53 La extorsión, el robo con vio- entre un cuatrimestre y otro. lencia y el robo de vehículos Con los datos obtenidos en se incrementaron en el último todo el país, el Observatorio Na- cuatrimestre de 2011 en el esta- cional Ciudadano indica que “si do de Colima, según el reporte la meta establecida en materia de periódico de monitoreo sobre seguridad pública ha sido dismi- delitos de alto impacto que ela- nuir los delitos que más lastiman bora el Observatorio Nacional a la sociedad, las actuales estra- Ciudadano. tegias no parecen haber ponde- Dichas cifras, recopiladas rado con sufi ciente precisión y por ese organismo ciudadano alcance dicho objetivo”. con base en las denuncias pre- sentadas ante las instancias LOCAL A 3 procuradoras de justicia, tam- bién señalan que durante 2011 se registraron 165 homicidios Ordenan al dolosos en la entidad. Según el análisis, difundido desde hace varios días en la pági- PAN reponer na electrónica www.observato- rionacionalciudadano.org.mx, el delito de la extorsión creció elección de un 150 por ciento del segundo Alberto Medina/DIARIO DE COLIMA al tercer cuatrimestre del año pasado, mientras que el robo de candidatos RIESGO vehículos, un 24.8 por ciento en ese mismo periodo. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

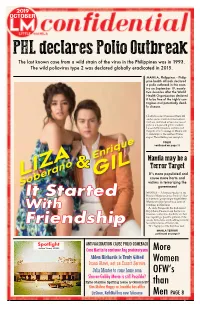

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

Philippine Labor Group Endorses Boycott of Pacific Beach Hotel

FEATURE PHILIPPINE NEWS MAINLAND NEWS inside look Of Cory and 5 Bishop Dissuades 11 Filipina Boxer 14 AUG. 29, 2009 Tech-Savvy Spiritual Leaders from to Fight for Filipino Youth Running in 2010 World Title H AWAII’ S O NLY W EEKLY F ILIPINO - A MERICAN N EWSPAPER PHILIPPINE LABOR GROUP ENDORSES BOYCOTT OF PACIFIC BEACH HOTEL By Aiza Marie YAGO hirty officers and organizers from different unions conducted a leafleting at Sun Life Financial’s headquarters in Makati City, Philippines last August 20, in unity with the protest of Filipino T workers at the Pacific Beach Hotel in Waikiki. The Trade Union Congress of the ternational financial services company, is Philippines (TUCP) had passed a resolu- the biggest investor in Pacific Beach Hotel. tion to boycott Pacific Beach Hotel. The Sun Life holds an estimated US$38 million resolution calls upon hotel management to mortgage and is in the process of putting rehire the dismissed workers and settle up its market in the Philippines. the contract between the union and the “If Sun Life wants to do business in company. the Philippines, the very least we can ex- Pacific Beach Hotel has been pect in return is that it will guarantee fair charged by the U.S. government with 15 treatment for Filipino workers in the prop- counts of federal Labor Law violations, in- erties it controls,” says Democrito Men- cluding intimidation, coercion and firing doza, TUCP president. employees for union activism. In Decem- Rhandy Villanueva, spokesperson for ber 2007, the hotel’s administration re- employees at Pacific Beach Hotel, was fused to negotiate with the workers’ one of those whose position was termi- legally-elected union and terminated 32 nated. -

Filipino Film-Based Instructional Plan for Pre Service Education Students

International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning Filipino Film-Based Instructional Plan for Pre Service Education Students Leynard L. Gripal* University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines. * Corresponding author. Tel.: 632 981 85 00 local 3404; email: [email protected] Manuscript submitted August 20, 2015; accepted December 15, 2015. doi: 10.17706/ijeeee.2016.6.1.56-70 Abstract: A Filipino film-based instructional plan was implemented in a pre service education class offered at a polytechnic college in Marikina City Philippines. Modified Dick & Reiser’s instructional plan and two films about Filipino school teachers were utilized in this study which is descriptive and quasi-experimental in nature. The qualitative measures include selection of film and effects of the created instructional plan. The quasi-experimental measures include implementation of the plan to the students. Simple student survey, post-survey of student’s feedback and focus group discussion feedback were used to analyze the study. The results stated that the films Munting Tining by Gil Portes and Mila by Joel Lamangan are good full length films that showed Filipino school teacher. A well-designed and –prepared Filipino film-based instructional plan that is based on the 1996 modified instructional plan by Dick & Reiser is a great aid in teaching pre-service education students. The created Filipino film-based instructional plan made impact to pre service education students. Key words: Dick & Reiser, Filipino film, instructional design, learning, teaching. 1. Introduction The ever changing technological environment renders interrelated and connected in a world. Communities, institutions and people including educators are challenged to answer to the call of globalization through various means, one of which is technology awareness. -

Catalogue 2010

EQUIPO CINES DEL SUR Director_José Sánchez-Montes I Relaciones institucionales_Enrique Moratalla I Directores de programación_Alberto Elena, Casimiro Torreiro I Asesores de programación_María Luisa Ortega, Esteve Riambau I Programador Transcine y cinesdelsur.ext_ ÍNDICE José Luis Chacón I Gerencia_Elisabet Rus I Auxiliar administración_Nuria García I Documentación Audiovisual Festival_Jorge Rodríguez Puche, Rafael Moya Cuadros I Coordinador Producción_Enrique Novi I Producción_Clara Ruiz Molina, Daniel Fortanet I Coordinadora de comunicación, difusión y prensa_María Vázquez I Auxiliares de comunicación, difusión y prensa_ Ramón Antequera, Anne Munzert, Ana Cabello, José Manuel Peña I Jefa de prensa_Nuria Díaz I Comunicación y prensa_Estela 7 Presentación_Welcome Hernández, Isabel Díaz, Neus Molina I Márketing_José Ángel Martínez I Publicaciones_Carlos Martín I Catálogo_Laura 11 Jurado 2010_Jury 2010 Montero Plata I Gestión de programación, tráfico de copias y material promocional_Reyes Revilla I Auxiliares de programación, tráfico de copias y material promocional_Zsuzsi Gruber, Frederique Bernardis I Relaciones con la industria_Nina Frese I Auxiliar relaciones con la industria_Bram Hermans I Relaciones públicas_Magdalena 19 PROGRAMACIÓN_Programming Lorente I Coordinador de invitados_Enrique Novi I Invitados_Marichu Sanz de Galdeano, Toni Anguiano I Asesor Consejería de Cultura_Benito Herrera I Protocolo_María José Gómez I Web_Enrique Herrera, María Vázquez I 21 Secciones Oficial e Itinerarios_Official and Itineraries Sections Coordinador -

Special Issue on Film Criticism

semi-annual peer-reviewed international online journal VOL. 93 • NO. 1 • MAY 2020 of advanced research in literature, culture, and society UNITAS SPECIAL ISSUE ON FILM CRITICISM ISSN: 0041-7149 Indexed in the International Bibliography of the ISSN: 2619-7987 Modern Language Association of America About the Issue Cover From top to bottom: 1. Baconaua - One Big Fight Productions & Waning Crescent Arts (2017); 2. Respeto - Dogzilla, Arkeofilms, Cinemalaya, CMB Film Services, & This Side Up (2017); 3. Ebolusyon ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino - Sine Olivia, Paul Tañedo Inc., & Ebolusyon Productions (2004); 4. Himala - Experimental Cinema of the Philippines (1982); and 5. That Thing Called Tadhana - Cinema One Originals, Epicmedia, Monoxide Works, & One Dash Zero Cinetools (2014). UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). UNITAS is published by the University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines, the oldest university in Asia. It is hosted by the Department of Literature, with its editorial address at the Office of the Scholar-in-Residence under the auspices of the Faculty of Arts and Letters. Hard copies are printed on demand or in a limited edition. Copyright @ University of Santo Tomas Copyright The authors keep the copyright of their work in the interest of advancing knowl- edge but if it is reprinted, they are expected to acknowledge its initial publication in UNITAS. Although downloading and printing of the articles are allowed, users are urged to contact UNITAS if reproduction is intended for non-individual and non-commercial purposes. Reproduction of copies for fair use, i.e., for instruction in schools, colleges and universities, is allowed as long as only the exact number of copies needed for class use is reproduced.