Michal Gruszczyrski Hardgrounds And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emplacement of the Jurassic Mirdita Ophiolites (Southern Albania): Evidence from Associated Clastic and Carbonate Sediments

Int J Earth Sci (Geol Rundsch) (2012) 101:1535–1558 DOI 10.1007/s00531-010-0603-5 ORIGINAL PAPER Emplacement of the Jurassic Mirdita ophiolites (southern Albania): evidence from associated clastic and carbonate sediments Alastair H. F. Robertson • Corina Ionescu • Volker Hoeck • Friedrich Koller • Kujtim Onuzi • Ioan I. Bucur • Dashamir Ghega Received: 9 March 2010 / Accepted: 15 September 2010 / Published online: 11 November 2010 Ó Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Sedimentology can shed light on the emplace- bearing pelagic carbonates of latest (?) Jurassic-Berrasian ment of oceanic lithosphere (i.e. ophiolites) onto continental age. Similar calpionellid limestones elsewhere (N Albania; crust and post-emplacement settings. An example chosen N Greece) post-date the regional ophiolite emplacement. At here is the well-exposed Jurassic Mirdita ophiolite in one locality in S Albania (Voskopoja), calpionellid lime- southern Albania. Successions studied in five different stones are gradationally underlain by thick ophiolite-derived ophiolitic massifs (Voskopoja, Luniku, Shpati, Rehove and breccias (containing both ultramafic and mafic clasts) that Morava) document variable depositional processes and were derived by mass wasting of subaqueous fault scarps palaeoenvironments in the light of evidence from compara- during or soon after the latest stages of ophiolite emplace- ble settings elsewhere (e.g. N Albania; N Greece). Ophiolitic ment. An intercalation of serpentinite-rich debris flows at extrusive rocks (pillow basalts and lava breccias) locally this locality is indicative of mobilisation of hydrated oceanic retain an intact cover of oceanic radiolarian chert (in the ultramafic rocks. Some of the ophiolite-derived conglom- Shpati massif). Elsewhere, ophiolite-derived clastics typi- erates (e.g. -

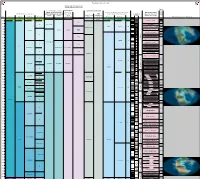

Expanded Jurassic Timescale

TimeScale Creator 2012 chart Russian and Ural regional units Russia Platform regional units Calca Jur-Cret boundary regional Russia Platform East Asian regional units reous stages - British and Boreal Stages (Jur- Australia and New Zealand regional units Marine Macrofossils Nann Standard Chronostratigraphy British regional Boreal regional Cret, Perm- Japan New Zealand Chronostratigraphy Geomagnetic (Mesozoic-Paleozoic) ofossil stages stages Carb & South China (Neogene & Polarity Tethyan Ammonoids s Ma Period Epoch Age/Stage Substage Cambrian) stages Cret) NZ Series NZ Stages Global Reconstructions (R. Blakey) Ryazanian Ryazanian Ryazanian [ no stages M17 CC2 Cretaceous Early Berriasian E Kochian Taitai Um designated ] M18 CC1 145 Berriasella jacobi M19 NJT1 Late M20 7b 146 Lt Portlandian M21 Durangites NJT1 M22 7a 147 Oteke Puaroan Op M22A Micracanthoceras microcanthum NJT1 Penglaizhenian M23 6b 148 Micracanthoceras ponti / Volgian Volgian Middle M24 Burckhardticeras peroni NJT1 Tithonian M24A 6a 149 M24B Semiformiceras fallauxi NJT15 M25 b E 150 M25A Semiformiceras semiforme NJT1 5a Early M26 Semiformiceras darwini 151 lt-Oxf N M-Sequence Hybonoticeras hybonotum 152 Ohauan Ko lt-Oxf R Kimmeridgian Hybonoticeras beckeri 153 m- Lt Late Oxf N Aulacostephanus eudoxus 154 m- NJT14 Late Aspidoceras acanthicum Oxf R Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Crussoliceras divisum 155 155.431 Card- N Ataxioceras hypselocyclum 156 E Early e-Oxf Sutneria platynota R Idoceras planula Suiningian 157 Cal- Oxf N Epipeltoceras bimammatum 158 lt- Lt Callo -

Jahrbuch Der Geologischen Bundesanstalt

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Jahrbuch der Geologischen Bundesanstalt Jahr/Year: 2017 Band/Volume: 157 Autor(en)/Author(s): Baron-Szabo Rosemarie C. Artikel/Article: Scleractinian corals from the upper Aptian–Albian of the Garschella Formation of central Europe (western Austria; eastern Switzerland): The Albian 241- 260 JAHRBUCH DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Jb. Geol. B.-A. ISSN 0016–7800 Band 157 Heft 1–4 S. 241–260 Wien, Dezember 2017 Scleractinian corals from the upper Aptian–Albian of the Garschella Formation of central Europe (western Austria; eastern Switzerland): The Albian ROSEMARIE CHRistiNE BARON-SZABO* 2 Text-Figures, 2 Tables, 2 Plates Österreichische Karte 1:50.000 Albian BMN / UTM western Austria 111 Dornbirn / NL 32-02-23 Feldkirch eastern Switzerland 112 Bezau / NL 32-02-24 Hohenems Garschella Formation 141 Feldkirch Taxonomy Scleractinia Contents Abstract ............................................................................................... 242 Zusammenfassung ....................................................................................... 242 Introduction............................................................................................. 242 Material................................................................................................ 243 Lithology and occurrence of the Garschella Formation ............................................................ 244 Albian scleractinian -

Systematic Paleontology.……………………………………………………18

A NOVEL ASSEMBLAGE OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEA, FROM A TITHONIAN CORAL REEF OLISTOLITH, PURCĂRENI, ROMANIA: SYSTEMATICAL ARRANGEMENT AND BIOGEOGRAPHICAL PERSPECTIVE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science by Aubrey M. Shirk December, 2006 Thesis written by Aubrey M. Shirk B.S., South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, 2003 M.S., Kent State University, 2006 Approved by _________________________________________, Advisor Dr. Rodney Feldmann _________________________________________, Chair, Department of Geology Dr. Donald Palmer _________________________________________, Associate Dean, College of Arts and Dr. John R. Stalvey Sciences ii DEPARMENT OF GEOLOGY THESIS APPROVAL FORM This thesis entitled A NOVEL ASSEMBLAGE OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEA, FROM A TITHONIAN CORAL REEF OLISTOLITH, PURCĂRENI, ROMANIA: SYSTEMATICAL ARRANGEMENT AND BIOGEOGRAPHICAL PERSPECTIVE has been submitted by Aubrey Mae Shirk in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Geology. The undersigned members of the student’s thesis committee have read this thesis and indicate their approval or disapproval of same. Approval Date Disapproval Date __________________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Rodney Feldmann 11/16/2006 ___________________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Carrie Schweitzer 11/16/2006 ___________________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Neil Wells 11/16/2006 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…..………………………………………………….………...xi -

Albian Corals from the Subpelagonian Zone of Central Greece (Agrostylia, Parnassos Region)

Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae (2002), vol. 72: 1-65. ALBIAN CORALS FROM THE SUBPELAGONIAN ZONE OF CENTRAL GREECE (AGROSTYLIA, PARNASSOS REGION) Elżbieta MORYCOWA1 & Anastasia MARCOPOULOU-DIACANTONI2 1 Institute o f Geological Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Oleandry 2a, 30-063 Kraków, Poland, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department o f Historical Geology and Paleontology, University o f Athens, Panepistimioupoli, 15784 Athens, Greece, e-mail: [email protected] Morycowa, E. & Marcopoulou-Diacantoni, A., 2002. Albian corals from the Subpelagonian Zone of Central Greece (Agrostylia, Pamassos region). Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae, 72: 1-65. Abstract: Shallow-water scleractinian corals from Cretaceous allochthonous sediments of the Subpelagonian Zone in Agrostylia (Pamassos region, Central Greece) represent 47 taxa belonging to 35 genera, 15 families and 8 suborders; of these 3 new genera and 9 new species are described. Among these taxa, 5 were identified only at the generic level. One octocorallian species has also been identified. This coral assemblage is representative for late Early Cretaceous Tethyan realm but also shows some endemism. A characteristic feature of this scleractinian coral assemblage is the abundance of specimens from the suborder Rhipidogyrina. The Albian age of the corals discussed is indicated by the whole studied coral fauna, associated foraminifers, calpionellids and calcareous dinoflagellates. Key words: Scleractinia, Octocorallia, Pamassos, Greece, Albian, taxonomy, palaeogeography. Manuscript received 3 December 2001, accepted 8 April 2002 INTRODUCTION Several occurrences of Cretaceous scleractinian corals and Morycowa & Kołodziej (2001) on corals from the from Greece have been mentioned in the literature (see e.g., Agrostylia valley in Pamassos (Albian, corrected from Al Celet, 1962), but not many taxonomic studies have been bian- ?Cenomanian). -

1501 Rogov.Vp

Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography MIKHAIL A. ROGOV & TERRY P. POULTON We present the first description of aulacostephanid (Perisphinctoidea) ammonites from the Kimmeridgian of Canada, and the first illustration of these ammonites in the Americas. These ammonites include Rasenia ex gr. cymodoce, Zenostephanus (Xenostephanoides) thurrelli, and Zonovia sp. A from British Columbia (western Canada). They belong to genera that are widely distributed in the subboreal Eurasian Arctic and Northwest Europe, and they also occur even in those Boreal regions dominated by cardioceratids. They are important markers for a narrow stratigraphic interval in the Cymodoce Zone (top of Lower Kimmeridgian) and the lower part of the Mutabilis Zone (base of Upper Kimmeridgian) of the Northwest European standard succession. In Spitsbergen and Franz Josef Land, the only Upper Kimmeridgian aulacostephanid-bearing level is the Zenostephanus (Zenostephanus) sachsi biohorizon, which very likely belongs to the Mutabilis Zone. Expansion of Zenostephanus from Eurasia, where it is present over a large area, into British Columbia, is approximately correlative with a transgressive event that also led to expansion of the Submediterranean ammonite ge- nus Crussoliceras through the Submediterranean and Subboreal areas slightly before Zenostephanus. • Key words: Kimmeridgian, aulacostephanids, Zenostephanus, Rasenia, British Columbia, palaeobiogeography, sea-level changes. ROGOV, M.A. & POULTON, T.P. 2015. Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography. Bulletin of Geosciences 90(1), 7–20 (5 figures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received January 31, 2014; ac- cepted in revised form October 2, 2014; published online November 25, 2014; issued January 26, 2015. -

Paleoecology ...Of ... Reefs from the Late Jurassic

Project: Le “Vergleichende Palokologie und Faziesentwicklung oberjurassischer Riffstrukturen des westlichen Tethys-Nordrandes * und des Lusitanischen Beckens (Zentraiportugal)/E, Project Leader: R. Leinfelder (Stuttgart) . Paleoecology, Growth Parameters and Dynamics of Coral, Sponge and Microbolite Reefs from the Late Jurassic Reinhold R. Werner, Martin Nose, Dieter U. Schmid, Laternser, Martin Takacs & Dorothea Area of Study: Portugal, Spain, Southern Germany, France, Poland Environment: Shallow to deep carbonate platforms Stratigraphy: Late Jurassic Organisms: Corals, siliceous sponges, microbes, microen- crusters Depositional Setting: Brackish-lagoonal to deep ramp set- tings Constructive Processes: Frame-building, baffling and binding (depending on reef type and type of reef- building organisms) Destructive Processes: Borings by bivalves and sponges; wave action Preservation: Mostly well preserved Research Topic: Comparative facies analysis and paleo- ecology of Upper Jurassic reefs, reef organisms and communities Spongiolitic facies Fig. I: Distribution of Upper Jurassic reefs studied in detail. Abstract framework and pronounced relief whenever microbolite crusts provided stabilization. Reefs in steepened slope set- Reefs from the Late Jurassic comprise various types of tings are generally rich in microbolites because of bypass coral reefs, siliceous sponge reefs and microbolite reefs. possibilities for allochthonous sediment. Reef rimmed shal- Upper Jurassic corals had a higher ratio of heterotrophic low-water platforms did occur but only developed on pre- versus autotrophic energy uptake than modern ones, which existing uplifts. Upper Jurassic sponge-microbolite mud explains their frequent occurrence in terrigenous settings. mounds grew in subhorizontal mid to outer ramp settings Coral communities changed along a bathymetric gradient and reflect a delicate equilibrium of massive and peloidal but sedimentation exerted a stronger control on diversities microbolite precipitation and accumulation of allochthonous than bathymetry. -

Earliest Known Lepisosteoid Extends the Range of Anatomically Modern Gars to the Late Jurassic Received: 25 September 2017 Paulo M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Earliest known lepisosteoid extends the range of anatomically modern gars to the Late Jurassic Received: 25 September 2017 Paulo M. Brito1, Jésus Alvarado-Ortega2 & François J. Meunier3 Accepted: 2 December 2017 Lepisosteoids are known for their evolutionary conservatism, and their body plan can be traced at Published: xx xx xxxx least as far back as the Early Cretaceous, by which point two families had diverged: Lepisosteidae, known since the Late Cretaceous and including all living species and various fossils from all continents, except Antarctica and Australia, and Obaichthyidae, restricted to the Cretaceous of northeastern Brazil and Morocco. Until now, the oldest known lepisosteoids were the obaichthyids, which show general neopterygian features lost or transformed in lepisosteids. Here we describe the earliest known lepisosteoid (Nhanulepisosteus mexicanus gen. and sp. nov.) from the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian – about 157 Myr), of the Tlaxiaco Basin, Mexico. The new taxon is based on disarticulated cranial pieces, preserved three-dimensionally, as well as on scales. Nhanulepisosteus is recovered as the sister taxon of the rest of the Lepisosteidae. This extends the chronological range of lepisosteoids by about 46 Myr and of the lepisosteids by about 57 Myr, and flls a major morphological gap in current understanding the early diversifcation of this group. Actinopterygians, or ray-finned fishes, are the largest group among extant gnathostoms vertebrates. Today actinopterygians are represented by three major clades: Cladistia (bichirs and rope fsh), with at least 16 species, Chondrostei (sturgeons and paddle fshes), with about 30 species, and Neopterygii, formed by the Teleostei, with about 30,000 species and the Holostei with eight species: one halecomorph (bowfn) and 7 ginglymodians (gars)1. -

Post-Mortem and Symbiotic Sabellid and Serpulid-Coral Associations from the Lower Cretaceous of Argentina

Rev. bras. paleontol. 14(3):215-228, Setembro/Dezembro 2011 © 2011 by the Sociedade Brasileira de Paleontologia doi:10.4072/rbp.2011.3.02 POST-MORTEM AND SYMBIOTIC SABELLID AND SERPULID-CORAL ASSOCIATIONS FROM THE LOWER CRETACEOUS OF ARGENTINA RICARDO M. GARBEROGLIO & DARÍO G. LAZO Instituto de Estudios Andinos “Don Pablo Groeber”, Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET, Pabellón II, Ciudad Universitaria, 1428, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] ABSTRACT – One morphotype of sabellids (Sabellida, Sabellidae) and two of serpulids (Sabellida, Serpulidae), found as encrusters on scleractinian ramose corals of the species Stereocaenia triboleti (Koby) and Columastrea antiqua Gerth, from the Agrio Formation (early Hauterivian) from Neuquén Basin, Argentina, are described. The identified morphotypes, Glomerula lombricus (Defrance), Mucroserpula mucroserpula Regenhardt and Propomatoceros sulcicarinatus Ware, have been previously recorded from the Early Cretaceous of the northern Tethys. Two different type of sabellid and serpulid- coral associations have been recognized. The first and more abundant association corresponds to post-mortem encrustation on corals branches. The second one corresponds to a symbiotic association between the serpulid P. sulcicarinatus and both species of corals. The serpulid tubes are recorded parallel to the coral branches reaching the upper tip of them and they were bioimmured within the coral as they grew upwards. The studied symbiotic relationship between serpulids and corals may be regarded as a mutualism as both members probably benefited each other. This type of association has similarities with recent cases of symbiosis between serpulids and corals, but had no fossil record until now. Key words: Serpulidae, Sabellidae, Scleractinia, symbiosis, Hauterivian, Argentina. -

The Mesozoic Corals. Bibliography 1758-1993

June, 1, 2020 The Mesozoic Corals. Bibliography 1758-1993. Supplement 24 ( -2019) Compiled by Hannes Löser1 Summary This supplement to the bibliography (published in the Coral Research Bulletin 1, 1994) contains 14 additional references to literary material on the taxonomy, palaeoecology and palaeogeography of Mesozoic corals (Triassic - Cretaceous; Scleractinia, Octocorallia). The bibliography is available in the form of a data bank with a menu-driven search program for Windows-compatible computers. Updates are available through the Internet (www.cp-v.de). Key words: Scleractinia, Octocorallia, corals, bibliography, Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, data bank Résumé Le supplément à la bibliographie (publiée dans Coral Research Bulletin 1, 1994) contient 14 autres références au sujet de la taxinomie, paléoécologie et paléogéographie des coraux mesozoïques (Trias - Crétacé; Scleractinia, Octocorallia). Par le service de mise à jour (www.cp-v.de), la bibliographie peut être livrée sur la base des données avec un programme de recherche contrôlée par menu avec un ordinateur Windows-compatible. Mots-clés: Scleractinia, Octocorallia, coraux, bibliographie, Trias, Jurassique, Crétacé, base des données Zusammenfassung Die Ergänzung zur Bibliographie (erschienen im Coral Research Bulletin 1, 1994) enthält 14 weitere Literaturzitate zur Taxonomie und Systematik, Paläoökologie und Paläogeographie der mesozoischen Korallen (Trias-Kreide; Scleractinia, Octocorallia). Die Daten sind als Datenbank zusammen mit einem menügeführten Rechercheprogramm für Windows-kompatible Computer im Rahmen eines Ände- rungsdienstes im Internet (www.cp-v.de) verfügbar. Schlüsselworte: Scleractinia, Octocorallia, Korallen, Bibliographie, Trias, Jura, Kreide, Datenbank 1 Estación Regional del Noroeste, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Hermosillo, Sonora, México; [email protected] © CPESS VERLAG 2020 • http://www.cp-v.de/crb • [email protected] 3 stone, which is diagenetically little altered. -

Evolutionary Trends in the Epithecate Scleractinian Corals

Evolutionary trends in the epithecate scleractinian corals EWA RONIEWICZ and JAROSEAW STOLARSKI Roniewicz, E. & Stolarski, J. 1999. Evolutionary trends in the epithecate scleractinian corals. -Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 44,2, 131-166. Adult stages of wall ontogeny of fossil and Recent scleractinians show that epitheca was the prevailing type of wall in Triassic and Jurassic corals. Since the Late Cretaceous the fre- quency of epithecal walls during adult stages has decreased. In the ontogeny of Recent epithecate corals, epitheca either persists from the protocorallite to the adult stage, or is re- placed in post-initial stages by trabecular walls that are often accompanied by extra- -calicular skeletal elements. The former condition means that the polyp initially lacks the edge zone, the latter condition means that the edge zone develops later in coral ontogeny. Five principal patterns in wall ontogeny of fossil and Recent Scleractinia are distinguished and provide the framework for discrimination of the four main stages (grades) of evolu- tionary development of the edge-zone. The trend of increasing the edge-zone and reduction of the epitheca is particularly well represented in the history of caryophylliine corals. We suggest that development of the edge-zone is an evolutionary response to changing envi- ronment, mainly to increasing bioerosion in the Mesozoic shallow-water environments. A glossary is given of microstructural and skeletal terms used in this paper. Key words : Scleractinia, microstructure, thecal structures, epitheca, phylogeny. Ewa Roniewicz [[email protected]]and Jarostaw Stolarski [[email protected]], Instytut Paleobiologii PAN, ul. Twarda 51/55, PL-00-818 Warszawa, Poland. In Memory of Gabriel A. -

Abstracts and Program. – 9Th International Symposium Cephalopods ‒ Present and Past in Combination with the 5Th

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265856753 Abstracts and program. – 9th International Symposium Cephalopods ‒ Present and Past in combination with the 5th... Conference Paper · September 2014 CITATIONS READS 0 319 2 authors: Christian Klug Dirk Fuchs University of Zurich 79 PUBLICATIONS 833 CITATIONS 186 PUBLICATIONS 2,148 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Exceptionally preserved fossil coleoids View project Paleontological and Ecological Changes during the Devonian and Carboniferous in the Anti-Atlas of Morocco View project All content following this page was uploaded by Christian Klug on 22 September 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. in combination with the 5th International Symposium Coleoid Cephalopods through Time Abstracts and program Edited by Christian Klug (Zürich) & Dirk Fuchs (Sapporo) Paläontologisches Institut und Museum, Universität Zürich Cephalopods ‒ Present and Past 9 & Coleoids through Time 5 Zürich 2014 ____________________________________________________________________________ 2 Cephalopods ‒ Present and Past 9 & Coleoids through Time 5 Zürich 2014 ____________________________________________________________________________ 9th International Symposium Cephalopods ‒ Present and Past in combination with the 5th International Symposium Coleoid Cephalopods through Time Edited by Christian Klug (Zürich) & Dirk Fuchs (Sapporo) Paläontologisches Institut und Museum Universität Zürich, September 2014 3 Cephalopods ‒ Present and Past 9 & Coleoids through Time 5 Zürich 2014 ____________________________________________________________________________ Scientific Committee Prof. Dr. Hugo Bucher (Zürich, Switzerland) Dr. Larisa Doguzhaeva (Moscow, Russia) Dr. Dirk Fuchs (Hokkaido University, Japan) Dr. Christian Klug (Zürich, Switzerland) Dr. Dieter Korn (Berlin, Germany) Dr. Neil Landman (New York, USA) Prof. Pascal Neige (Dijon, France) Dr.