Ceratosphinctes (Ammonitina, Kimmeridgian)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New and Poorly Known Perisphinctoidea (Ammonitina) from the Upper Tithonian of Le Chouet (Drôme, SE France)

Volumina Jurassica, 2014, Xii (1): 113–128 New and poorly known Perisphinctoidea (Ammonitina) from the Upper Tithonian of Le Chouet (Drôme, SE France) Luc G. BULOT1, Camille FRAU2, William A.P. WIMBLEDON3 Key words: Ammonoidea, Ataxioceratidae, Himalayitidae, Neocomitidae, Upper Tithonian, Le Chouet, South-East France. Abstract. The aim of this paper is to document the ammonite fauna of the upper part of the Late Tithonian collected at the key section of Le Chouet (Drôme, SE France). Emphasis is laid on new and poorly known Ataxioceratidae, Himalayitidae and Neocomitidae from the upper part of the Tithonian. Among the Ataxioceratidae, a new account on the taxonomy and relationship between Paraulacosphinctes Schindewolf and Moravisphinctes Tavera is presented. Regarding the Himalayitidae, the range and content of Micracanthoceras Spath is discussed and two new genera are introduced: Ardesciella gen. nov., for a group of Mediterranean ammonites that is homoeomorphic with the Andean genus Corongoceras Spath, and Pratumidiscus gen. nov. for a specimen that shows morphological similarities with the Boreal genera Riasanites Spath and Riasanella Mitta. Finally, the occurrence of Neocomitidae in the uppermost Tithonian is documented by the presence of the reputedly Berriasian genera Busnardoiceras Tavera and Pseudargentiniceras Spath. INTRODUCTION known Perisphinctoidea from the Upper Tithonian of this reference section. Additional data on the Himalayitidae in- The unique character of the ammonite fauna of Le Chouet cluding the description and discussion of Boughdiriella (near Les Près, Drôme, France) (Fig. 1) has already been chouetensis gen. nov. sp. nov. are to be published elsewhere outlined by Le Hégarat (1973), but, so far, only a handful of (Frau et al., 2014). -

Decapode.Pdf

We are pleased and honored to welcome at the Paléospace Museum of Villers-sur-Mer the “6th Symposium on Mesozoic and Cenozoic Decapod Crustaceans”. Villers-sur-Mer is a place universally known by specialists and amateurs of palaeontology due to its famous Vaches Noires cliffs. Villers-sur-Mer has also the distinction of being the only French seaside resort located on the Greenwich Meridian line. The Paléospace is a Museum funded in 2011 with the label Musée de France. Three main animations linked to the Time are presented: palaeontology, astronomy and nature with the neighbouring marsh. The museum is in a constant evolution. For instance, an exhibition specially dedicated to dinosaurs was opened two years ago and a planetarium will open next summer. Every year a very high quality temporary exhibition takes place during the summer period with very numerous animations during all the year. The Paléospace does not stop progressing in term of visitors (56 868 in 2015) and its notoriety is universally recognized both by the other museums as by the scientific community. We are very proud of these unexpected results. We thank the dynamism and the professionalism of the Paléospace team which is at the origin of this very great success. We wish you a very good stay at Villers-sur-Mer, a beautiful visit of the Paléospace and especially an excellent congress. Jean-Paul Durand, Mayor and President of Paléospace MOT DU MAIRE DE VILLERS-SUR-MER Nous sommes très heureux et très honorés d’accueillir à Villers-sur-Mer, le « 6e Symposium on Mesozoic and Cenozoic Decapod Crustaceans » dans le cadre du Paléospace. -

First Three-Dimensionally Preserved in Situ Record of an Aptychophoran Ammonite Jaw Apparatus in the Jurassic and Discussion of the Function of Aptychi

Berliner paläobiologische Abhandlungen 10 321-330 Berlin 2009-11-11 First three-dimensionally preserved in situ record of an aptychophoran ammonite jaw apparatus in the Jurassic and discussion of the function of aptychi Günter Schweigert Abstract: A unique specimen of the microconch ammonite Lingulaticeras planulatum Berckhemer in Ziegler, 1958 comes from a tempestite bed within the Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones of Scham- haupten in Franconia (Painten Formation, uppermost Kimmeridgian). The shell is unique because it retains the complete jaw apparatus in the body chamber. The articulation of the Lamellaptychus and the corresponding upper beak are well preserved. The function of the aptychus is discussed in general, and an operculum function is thought to be unlikely. The formation of strongly calcified aptychi in aspidoceratids and some oppeliid ammonoids is interpreted as an added ballast weight to stabilize the conch for swimming in the water column. Keywords: Ammonites, aptychus, preservation, functional morphology, Upper Jurassic, lithographic lime- stones, Franconia, Germany Zusammenfassung: Ein einzigartig erhaltenes Exemplar des mikroconchen Ammoniten Lingulaticeras planulatum Berckhemer in Ziegler, 1958 aus einer Tempestitlage des oberjurassischen Plattenkalks von Schamhaupten in Franken (Painten-Formation, oberstes Kimmeridgium) enthält noch den vollständigen Kieferapparat in seiner Wohnkammer.Es zeigt die perfekte Artikualation des Lamellaptychus mit dem dazu- gehörenden Oberkiefer. Die Funktion des Aptychus wird allgemein diskutiert und eine Deckelfunktion für unwahrscheinlich gehalten. Die Ausbildung stark verkalkter Aptychen wie in Aspidoceraten und manchen Oppeliiden wird als zusätzliches Tariergewicht gedeutet, um das Gehäuse in starker bewegtem Wasser zu stabilisieren. Schlüsselwörter: Ammoniten, Aptychus, Erhaltung, Plattenkalke, Funktionsmorphologie, Oberjura, Franken, Deutschland Address of the author: Dr. Günter Schweigert, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Rosenstein 1, D-70191 Stuttgart. -

New Data on the Jaw Apparatus of Fossil Cephalopods

New dataon the jaw apparatus of fossil cephalopods YURI D. ZAKHAROV AND TAMAZ A. LOMINADZE \ Zakharov, Yuri D. & Lominadze, Tamaz A. 19830115: New data on the jaw apparatus of fossil LETHAIA cephalopods. Lethaia, Vol. 16, pp. 67-78. Oslo. ISSN 0024-1164. A newly discovered fossil cephalopod jaw apparatus that may belong to Permian representatives of the Endocochlia is described. Permorhynchus dentatus n. gen. n. sp. is established on the basis of this ~ apparatus. The asymmetry of jaws in the Ectocochlia may be connected with the double function of the ventral jaw apparatus, and the well-developed, relatively large frontal plate of the ventral jaw should be regarded as a feature common to all representatives of ectocochlian cephalopods evolved from early Palaeozoic stock. Distinct features seen in the jaw apparatus of Upper Pcrmian cndocochlians include the pronounced beak form of both jaws and the presence of oblong wings on the ventral mandible. o Cephalopoda. jaw. operculum. aptychus, anaptychus, Permorhynchus n.gen.• evolution. Permian. Yuri D. Zakharov llOpllll Ilscumpueeu« Gaxapoe], Institute of Biology and Pedology, Far-Eastern Scientific Centre. USSR Academy of Science, Vladivostok 690022, USSR (EUOJl020-n9~BnlHbliiuucmu my m Ilaot.neeocmo-cnoro Ha."~H020 uenmpav Axaoeuuu 'HayK CCCP, Bnaoueocmo« 690022, CCCP); Tamaz A. Lominadze ITa.'W3 Apl.j1L10BUl.j Jlouunaoee), Institute of Palaeobiology of Georgian SSR Academy of Science. Tbilisi 380004. USSR (Hncmumvm naJle06UOJl02UU Atcaoeuuu naytc TpY3UHUjKOii CCP. T6'LJUCU 380004. CCP; 19th August. 1980 (revised 1982 06 28). The jaw apparatus of Recent cephalopods is re Turek 1978, Fig. 7, but not the reconstruction in presented by two jaw elements (Fig. -

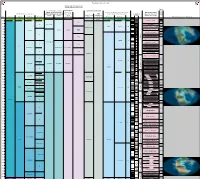

Expanded Jurassic Timescale

TimeScale Creator 2012 chart Russian and Ural regional units Russia Platform regional units Calca Jur-Cret boundary regional Russia Platform East Asian regional units reous stages - British and Boreal Stages (Jur- Australia and New Zealand regional units Marine Macrofossils Nann Standard Chronostratigraphy British regional Boreal regional Cret, Perm- Japan New Zealand Chronostratigraphy Geomagnetic (Mesozoic-Paleozoic) ofossil stages stages Carb & South China (Neogene & Polarity Tethyan Ammonoids s Ma Period Epoch Age/Stage Substage Cambrian) stages Cret) NZ Series NZ Stages Global Reconstructions (R. Blakey) Ryazanian Ryazanian Ryazanian [ no stages M17 CC2 Cretaceous Early Berriasian E Kochian Taitai Um designated ] M18 CC1 145 Berriasella jacobi M19 NJT1 Late M20 7b 146 Lt Portlandian M21 Durangites NJT1 M22 7a 147 Oteke Puaroan Op M22A Micracanthoceras microcanthum NJT1 Penglaizhenian M23 6b 148 Micracanthoceras ponti / Volgian Volgian Middle M24 Burckhardticeras peroni NJT1 Tithonian M24A 6a 149 M24B Semiformiceras fallauxi NJT15 M25 b E 150 M25A Semiformiceras semiforme NJT1 5a Early M26 Semiformiceras darwini 151 lt-Oxf N M-Sequence Hybonoticeras hybonotum 152 Ohauan Ko lt-Oxf R Kimmeridgian Hybonoticeras beckeri 153 m- Lt Late Oxf N Aulacostephanus eudoxus 154 m- NJT14 Late Aspidoceras acanthicum Oxf R Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Crussoliceras divisum 155 155.431 Card- N Ataxioceras hypselocyclum 156 E Early e-Oxf Sutneria platynota R Idoceras planula Suiningian 157 Cal- Oxf N Epipeltoceras bimammatum 158 lt- Lt Callo -

First Record of Non-Mineralized Cephalopod Jaws and Arm Hooks

Klug et al. Swiss J Palaeontol (2020) 139:9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-020-00210-y Swiss Journal of Palaeontology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access First record of non-mineralized cephalopod jaws and arm hooks from the latest Cretaceous of Eurytania, Greece Christian Klug1* , Donald Davesne2,3, Dirk Fuchs4 and Thodoris Argyriou5 Abstract Due to the lower fossilization potential of chitin, non-mineralized cephalopod jaws and arm hooks are much more rarely preserved as fossils than the calcitic lower jaws of ammonites or the calcitized jaw apparatuses of nautilids. Here, we report such non-mineralized fossil jaws and arm hooks from pelagic marly limestones of continental Greece. Two of the specimens lie on the same slab and are assigned to the Ammonitina; they represent upper jaws of the aptychus type, which is corroborated by fnds of aptychi. Additionally, one intermediate type and one anaptychus type are documented here. The morphology of all ammonite jaws suggest a desmoceratoid afnity. The other jaws are identifed as coleoid jaws. They share the overall U-shape and proportions of the outer and inner lamellae with Jurassic lower jaws of Trachyteuthis (Teudopseina). We also document the frst belemnoid arm hooks from the Tethyan Maastrichtian. The fossils described here document the presence of a typical Mesozoic cephalopod assemblage until the end of the Cretaceous in the eastern Tethys. Keywords: Cephalopoda, Ammonoidea, Desmoceratoidea, Coleoidea, Maastrichtian, Taphonomy Introduction as jaws, arm hooks, and radulae are occasionally found Fossil cephalopods are mainly known from preserved (Matern 1931; Mapes 1987; Fuchs 2006a; Landman et al. mineralized parts such as aragonitic phragmocones 2010; Kruta et al. -

Revisión De Los Ammonoideos Del Lías Español Depositados En El Museo Geominero (ITGE, Madrid)

Boletín Geológico y Minero. Vol. 107-2 Año 1996 (103-124) El Instituto Tecnológico Geominero de España hace presente que las opiniones y hechos con signados en sus publicaciones son de la exclusi GEOLOGIA va responsabilidad de los autores de los trabajos. Revisión de los Ammonoideos del Lías español depositados en el Museo Geominero (ITGE, Madrid). Por J. BERNAD (*) y G. MARTINEZ. (**) RESUMEN Se revisan desde el punto de vista taxonómico, los fósiles de ammonoideos correspondientes al Lías español que se encuentran depositados en el Museo Geominero. La colección está compuesta por ejemplares procedentes de 67 localida des españolas, pertenecientes a colecciones de diferentes autores. Se identifican los ordenes Phylloceratina, Lytoceratina y Ammonitina, las familias Phylloceratidae, Echioceratidae, eoderoceratidae, Liparoceratidae, Amaltheidae, Dactyliocerati Los derechos de propiedad de los trabajos dae, Hildoceratidae y Hammatoceratidae y las subfamilias Xipheroceratinae, Arieticeratinae, Harpoceratinae, Hildocerati publicados en esta obra fueron cedidos por nae, Grammoceratinae, Phymatoceratinae y Hammatoceratinae correspondientes a los pisos Sinemuriense, Pliensbachien los autores al Instituto Tecnológico Geomi se y Toarciense. nero de España Oueda hecho el depósito que marca la ley. Palabras clave: Ammonoidea, Taxonomía, Lías, España, Museo Geominero. ABSTRACT The Spanish Liassic ammonoidea fossil collections of the Geominero Museum is revised under a taxonomic point of view. The collection includes specimens from 67 Spanish -

STUTTGARTER BEITRÄGE ZUR NATURKUNDE Ser

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Stuttgarter Beiträge Naturkunde Serie B [Paläontologie] Jahr/Year: 1998 Band/Volume: 267_B Autor(en)/Author(s): Schweigert Günter Artikel/Article: Die Ammonitenfauna des Nusplinger Plattenkalks (Ober- Kimmeridgium, Beckeri-Zone, Ulmense-Subzone, Baden-Württemberg) 1-61 1 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at pw Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunj Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie)! ty Herausgeber: ^ v^O , Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Rosenstein 1, D-70191 StuttgansAcv* Stuttgarter Beitr. Naturk. Ser. B Nr. 267 61 S., 12 Taf., 3 Abb., 1 Tab. Stuttgart, 30. 10. Die Ammonitenfauna des Nusplinger Plattenkalks (Ober-Kimmeridgium, Beckeri-Zone, Ulmense-Subzone, Baden-Württemberg) The ammonite fauna of the Nusplingen Lithographie Limestone (Late Kimmeridgian, Beckeri Zone, Ulmense Subzone, SW Germany) Von Günter Schweigert, Stuttgart Mit 12 Tafeln, 3 Abbildungen und 1 Tabelle Abstract The ammonite fauna of the Nusplingen Lithographie Limestone (Swabian Upper Jurassic) is described in detail. It is compared with non-compressed faunas of the same age. With the exception of the lowermost part of the section the ammonite fauna of the Nusplingen Litho- graphie Limestone is attributed to the hoelderi horizon of the Ulmense Subzone (Beckeri Zone, Late Kimmeridgian). The basal parts of the Nusplingen Lithographie Limestone yield an ammonite faunula which represents the zio-wepferi horizon ß of the Ulmense Subzone. In other parts of the Swabian Alb both the zio-wepferi horizon ß and the sueeeeding hoelderi ho- rizon lie in the „Liegende Bankkalke" or in the „Zementmergel" Formations. Both ammonite faunas show a submediterranean character with only very few mediterranean and subboreal faunal elements. -

Oxfordian Idoceratids (Ammonoidea) and Their Relation to Perisphinctes Proper

ACT A PAL A EON T 0 L ,0 GI CAP 0 LON ICA Vol. 21 1976 No 4 WOJCIECH BROCHWICZ-LEWINSKI & ZDZISLAW ROZAK OXFORDIAN IDOCERATIDS (AMMONOIDEA) AND THEIR RELATION TO PERISPHINCTES PROPER Abstract. - An attempt is made to reconstruct the evolution of idoceratids (Pe risphinctidae) during the Oxfordian. The subgenus Nebrodites (Passendorjeria) is supposed to be the ancestor of N. (Mesosimoceras), whilst N. (Enayites) subgen. n. of N. (Nebrodites) and possibly of Idoceras planula group. Both genera appear to be of European origin. Differentiation of Mediterranean and Submediterran.ean peris phinctidae appears questionable. INTRODUCTION In 1973 one of the co-authors (W. Brochwicz-Lewiilski, 1973) proposed a new subgenus Nebrodites (Passendorferia) for Middle Oxfordian forms interpreted as descendants of Mediterranean Kranaosphinctes cyrilli-me thodii group and ancestors of Nebrodites proper; the Idoceras planula group was assumed to be an off-shoot of the evolutionary line. Subsequent collecting gave several Passendorferia and Passendorferia-like forms from the Oxfordian of Poland, Switzerland (Gygi, pers. inf.), Spain (Sequeiros, 1974) and Bulgaria (Sapunov, in press). Moreover, ancestral forms of the Idoceras planula group were reported from the Bimammatum Zone of the F. R. G. (Nitzopoulos, 1974). These finds made it possible to draw some conclusions concerning the h~tory of these Mediterranean perisphinctids and their relationship to the Submediterranean ones. The material described comprises forms from authors' G. KU'lesza (Br, Kl) and Dr. J. Liszkowski's (L) collections housed at the Warsaw University as well as others from the Geological Museum of Sofia Univer sity (Bulgaria) and Geological Museum of the Polish Academy of Sciences at Cracow. -

Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) Cold-Water Idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from Southern Coahuila, Northeastern Mexico, Associated with Boreal Bivalves and Belemnites

REVISTA MEXICANA DE CIENCIAS GEOLÓGICAS Kimmeridgian cold-water idoceratids associated with Boreal bivalvesv. 32, núm. and 1, 2015, belemnites p. 11-20 Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) cold-water idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from southern Coahuila, northeastern Mexico, associated with Boreal bivalves and belemnites Patrick Zell* and Wolfgang Stinnesbeck Institute for Earth Sciences, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 234, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. *[email protected] ABSTRACT et al., 2001; Chumakov et al., 2014) was followed by a cool period during the late Oxfordian-early Kimmeridgian (e.g., Jenkyns et al., Here we present two early Kimmeridgian faunal assemblages 2002; Weissert and Erba, 2004) and a long-term gradual warming composed of the ammonite Idoceras (Idoceras pinonense n. sp. and trend towards the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (e.g., Abbink et al., I. inflatum Burckhardt, 1906), Boreal belemnites Cylindroteuthis 2001; Lécuyer et al., 2003; Gröcke et al., 2003; Zakharov et al., 2014). cuspidata Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964 and Cylindroteuthis ex. gr. Palynological data suggest that the latest Jurassic was also marked by jacutica Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964, as well as the Boreal bivalve Buchia significant fluctuations in paleotemperature and climate (e.g., Abbink concentrica (J. de C. Sowerby, 1827). The assemblages were discovered et al., 2001). in inner- to outer shelf sediments of the lower La Casita Formation Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous marine associations contain- at Puerto Piñones, southern Coahuila, and suggest that some taxa of ing both Tethyan and Boreal elements [e.g. ammonites, belemnites Idoceras inhabited cold-water environments. (Cylindroteuthis) and bivalves (Buchia)], were described from numer- ous localities of the Western Cordillera belt from Alaska to California Key words: La Casita Formation, Kimmeridgian, idoceratid ammonites, (e.g., Jeletzky, 1965), while Boreal (Buchia) and even southern high Boreal bivalves, Boreal belemnites. -

1501 Rogov.Vp

Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography MIKHAIL A. ROGOV & TERRY P. POULTON We present the first description of aulacostephanid (Perisphinctoidea) ammonites from the Kimmeridgian of Canada, and the first illustration of these ammonites in the Americas. These ammonites include Rasenia ex gr. cymodoce, Zenostephanus (Xenostephanoides) thurrelli, and Zonovia sp. A from British Columbia (western Canada). They belong to genera that are widely distributed in the subboreal Eurasian Arctic and Northwest Europe, and they also occur even in those Boreal regions dominated by cardioceratids. They are important markers for a narrow stratigraphic interval in the Cymodoce Zone (top of Lower Kimmeridgian) and the lower part of the Mutabilis Zone (base of Upper Kimmeridgian) of the Northwest European standard succession. In Spitsbergen and Franz Josef Land, the only Upper Kimmeridgian aulacostephanid-bearing level is the Zenostephanus (Zenostephanus) sachsi biohorizon, which very likely belongs to the Mutabilis Zone. Expansion of Zenostephanus from Eurasia, where it is present over a large area, into British Columbia, is approximately correlative with a transgressive event that also led to expansion of the Submediterranean ammonite ge- nus Crussoliceras through the Submediterranean and Subboreal areas slightly before Zenostephanus. • Key words: Kimmeridgian, aulacostephanids, Zenostephanus, Rasenia, British Columbia, palaeobiogeography, sea-level changes. ROGOV, M.A. & POULTON, T.P. 2015. Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography. Bulletin of Geosciences 90(1), 7–20 (5 figures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received January 31, 2014; ac- cepted in revised form October 2, 2014; published online November 25, 2014; issued January 26, 2015. -

Characteristic Jurassic Mollusks from Northern Alaska

Characteristic Jurassic Mollusks From Northern Alaska GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 274-D Characteristic Jurassic Mollusks From Northern Alaska By RALPH W. IMLAY A SHORTER CONTRIBUTION TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 274-D A study showing that the northern Alaskan faunal succession agrees with that elsewhere in the Boreal region and in other parts of North America and in northwest Europe UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - BMMH§ts (paper cover) Price $1.00 CONTENTS Page Abstract_________________ 69 Introduction _________________ 69 Biologic analysis____________ 69 Stratigraphic summary. _______ 70 Ages of fossils________________ 73 Comparisons with other faunas. 75 Ecological considerations___ _ 75 Geographic distribution____. 78 Summary of results ___________ 81 Systematic descriptions__ _. 82 Literature cited____________ 92 Index_____________________ 95 ILLUSTRATIONS [Plates &-13 follow Index] PLATE 8. Inoceramus and Gryphaea 9. Aucella 10. Amaltheus, Dactylioceras, "Arietites," Phylloceras, and Posidonia 11. Ludwigella, Dactylioceras, and Harpoceras. 12. Pseudocadoceras, Arcticoceras, Amoeboceras, Tmetoceras, Coeloceras, and Pseudolioceras 13. Reineckeia, Erycites, and Cylindroteuthis. Page FIGXTKE 20. Index map showing Jurassic fossil collection localities in northern Alaska.