The Increasing Sociospatial Fragmentation of Urban America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Business District Development in a Transition Economy – Case Studies of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, China

Central Business District Development in a Transition Economy – Case Studies of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, China Bo B. S. TANG and Stanley Chi-Wai YEUNG Department of Building and Real Estate, Hong Kong Polytechnic University Weiwen Li Shenzhen University, China Acknowledge This paper is based on the research project funded by the Direct RGC Grant to the Hong Kong Polytechnic University of Hong Kong A-P032 Key words: CBD Development, transition economy, China Abstract Since its implementation of economic reforms and open door policy, China has rapidly transformed itself from a socialist planned economy to socialist market economy. Guangzhou and Shanzhen are earmarked as the pioneering and experimental cities within the network of cities in Pearl River Delta Region in implementing various market reform measures. Taking advantage of its close proximity with Hong Kong and Macau, these two cities have achieved remarkable success in economic strength and become modernized commercial cities. Supported by the growth of tertiary industries such as finance. information technology, business and trading, property development in these two cities has also taken a rapid pace. CBD development can also be identifies. CBD development is a relatively new product within the development process of socialist China. Before the marketization reform, China’s socialist planned economy implied that the state was responsible for resource allocation. There was no room for market adjustment. Commercial retail areas replaced the position of CBD as the urban centres. When China adopted its open door policy and introduced market mechanism, the spatial structure of existing cities has begun to change. Business and trading activities outside the state planning process becomes increasingly important. -

Models of Urban Growth : Concentric Zones, Sectors, Multiple Nuclei, Explaitative, Syrn Bolic

Models of Urban Growth : Concentric Zones, Sectors, Multiple Nuclei, Explaitative, Syrn bolic 6.1 lntroduction 6.2 Structure of Cities 6.3 Concentric Zone Model . 6.4 Sectors Model 6.5 Multiple Nuclei Model 6.6 Exploitative Model 6.7 Symbolic Approach 6.8 Conclusion 6.9 Further Reading Learning Objectives After studying this unit you should be able to: discuss the structure of cities; describe the concentric zone model of studying the structure of cities; explain the sectors model; , describe the multiple nuclei model; discuss the exploitative model; and explain the symbolic approach to the study of city. 6.1 lntroduction Under the rubric of urban ecological process and theories, you have already learnt about the processes of invasion, succession, concentration, centralisation and segregation which characterise different kinds and dimensions of cities. Here in this unit you will learn further about the different aspects of cities and their formations. As you already know, urban society is defined as a relatively larger, dense, permanent, heterogeneous settlements whose majority of inhabitants are engaged in non-agricultural occupation. The development of such urban society is very much determined by socio - cultural organisation, climate, topography and economic development. The earliest cities of the world originated near river valleys such as early civilization of lndus (Mohenjodaro, Harrappa), Tigris - Eupharates (Lagas Ur, Uruk), Nile (Memphis, Thebes) 5 7 and Hwang Ho (Chen-Chan An Yang). These early development of urban settlements evolved with changing technology and human needs. Trade and commercial activities and settled agriculture were major facilitators; even today these,factors are very much relevant in the growth of a city. -

Compare and Contrast the Concentric, Sector and Multiple Nuclei Models

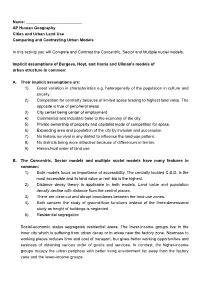

Name: _________________________ AP Human Geography Cities and Urban Land Use Comparing and Contrasting Urban Models In this activity you will Compare and Contrast the Concentric, Sector and Multiple nuclei models. Implicit assumptions of Burgess, Hoyt, and Harris and Ullman’s models of urban structure in common: A. Their implicit assumptions are: 1) Great variation in characteristics e.g. heterogeneity of the population in culture and society. 2) Competition for centrality because of limited space leading to highest land value. The opposite is true of peripheral areas. 3) City center being center of employment. 4) Commercial and industrial base to the economy of the city. 5) Private ownership of property and capitalist mode of competition for space. 6) Expanding area and population of the city by invasion and succession. 7) No historic survival in any district to influence the land-use pattern. 8) No districts being more attractive because of differences in terrain. 9) Hierarchical order of land use. B. The Concentric, Sector models and multiple nuclei models have many features in common: 1) Both models focus on importance of accessibility. The centrally located C.B.D. is the most accessible and its land value or rent-bid is the highest. 2) Distance decay theory is applicable in both models. Land value and population density decline with distance from the central places. 3) There are clear-cut and abrupt boundaries between the land-use zones. 4) Both concern the study of ground-floor functions instead of the three-dimensional study as height of buildings is neglected 5) Residential segregation Social-economic status segregates residential areas. -

Models of Urban Structure Residential Deterioration and Encroachment by Business and Light Manufacturing

Models of Urban Structure residential deterioration and encroachment by business and light manufacturing. The zone of independent Cities are not simply random collections of buildings and workers homes (3) was primarily occupied by the blue- people. They exhibit functional structure: they are collar (wage-earners, manual laborers) labor force. The spatially organized to perform their functions as places of zone of better residences (4) consisted mainly of the commerce, production, education, and much more. One middle-class. Finally, the commuters zone (5) was the of the most important forces determining where certain suburban ring, consisting mostly of white-collar workers buildings or activities are located within a city deals with who could afford to live further from the CBD. This the price of land. This tends to be the highest in the model was dynamic. As the city grew, the inner zones downtown area and declines as one moves outward from encroached on the outer ones. the center. The United States is the only country in the world in which the majority of the people live in the Remember, the model was developed for American cities suburbs. Even though house prices may be higher in the and had limited applicability elsewhere. It has been suburbs, the land value is lower (a downtown apartment demonstrated that pre-industrial cities, notably in Europe, complex will produce much more revenue per year than a did not at all followed the concentric circles model. For few suburban homes occupying the same amount of instance, in most pre-industrial European cities, the center space). In every other country the majority resides in was much more important than the periphery, notably in either rural or urban areas. -

Using the Urban Landscape Mosaic to Develop and Validate Methods for Assessing the Spatial Distribution of Urban Ecosystem Service Potential

USING THE URBAN LANDSCAPE MOSAIC TO DEVELOP AND VALIDATE METHODS FOR ASSESSING THE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF URBAN ECOSYSTEM SERVICE POTENTIAL Oliver Twanhaw GUNAWAN School of Environment and Life Sciences College of Science and Technology University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, July 2015 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... vii List of Tables .......................................................................................................... xiii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... xvii Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... xviii Abstract .................................................................................................................... xx 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Context of research .......................................................................................... 1 1.2. Ecosystem services in the urban environment .................................................. 2 1.3. Thesis structure ............................................................................................... -

Theories of Urban Growth

THEORIES OF URBAN GROWTH • Although several theories have been developed to explain the dynamics of city growth, all such theories are based upon the operation of five ecological processes of concentration, centralization, invasion and succession and observations based upon it about actual city growth in concrete situations. • However, one can hardly find a theory of an ideal pattern of urban dynamics as growth of particular city depends upon many factors, the basic one being natural location of a city .Nevertheless, one can notice a set of common principles which govern city growth everywhere • The major theories of internal structure of urban settlements have been advanced on the basis of empirical investigations conducted in the Western urban society, particularly in North America and Europe. • . Concentric zone model • Ernest Burgess is the pioneer and his theory on city dynamics which provides the base for the later theorists on the subject. The hypothesis of this theory is that cities grow and develop outwardly in concentric zones. Burgess set out to evolve a theory of dynamics but he arrived at a theory of patterns of city growth which applies to any stage stages of urban development. According to Burgess, an urban area consists of five concentric zones which represent areas of functional differentiation and expand rapidly from the Justness centre. The zones are: • (1) The loop or commercial centre • (2) The zone of transition. • (3) The zone of working class residence • (4) The residential zone of high class apartment buildings. • (5) The commuter's zone. 1. The loop or central business district or commercial centre: • 1. -

Models of Urban Growth : Concentric Zones, Sectors, Multiple Nuclei, Explaitative, Syrn Bolic

Models of Urban Growth : Concentric Zones, Sectors, Multiple Nuclei, Explaitative, Syrn bolic 6.1 lntroduction 6.2 Structure of Cities 6.3 Concentric Zone Model . 6.4 Sectors Model 6.5 Multiple Nuclei Model 6.6 Exploitative Model 6.7 Symbolic Approach 6.8 Conclusion 6.9 Further Reading Learning Objectives After studying this unit you should be able to: discuss the structure of cities; describe the concentric zone model of studying the structure of cities; explain the sectors model; , describe the multiple nuclei model; discuss the exploitative model; and explain the symbolic approach to the study of city. 6.1 lntroduction Under the rubric of urban ecological process and theories, you have already learnt about the processes of invasion, succession, concentration, centralisation and segregation which characterise different kinds and dimensions of cities. Here in this unit you will learn further about the different aspects of cities and their formations. As you already know, urban society is defined as a relatively larger, dense, permanent, heterogeneous settlements whose majority of inhabitants are engaged in non-agricultural occupation. The development of such urban society is very much determined by socio - cultural organisation, climate, topography and economic development. The earliest cities of the world originated near river valleys such as early civilization of lndus (Mohenjodaro, Harrappa), Tigris - Eupharates (Lagas Ur, Uruk), Nile (Memphis, Thebes) 5 7 and Hwang Ho (Chen-Chan An Yang). These early development of urban settlements evolved with changing technology and human needs. Trade and commercial activities and settled agriculture were major facilitators; even today these,factors are very much relevant in the growth of a city. -

Decentralization in Central Business District of City by Land Use Pattern

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-7 Issue-4, April 2018 Decentralization in Central Business District of City by Land Use Pattern Alteration to Promote Pedestrian Movement through Urban Design Strategies Case Study: Sabzevar City, Iran Ehsan Amini, Setareh Oruji Abstract: Cities are perhaps one of humanity’s most complex agglomeration economies. In Central Business District Major creations, never finished, never definitive. They are like a journey Characteristics is: that never ends. Their evolution is determined by their ascent into High accessibility • High land cost • High development greatness or their descent into decline. They are the past, the density • High living cost • Presence of tall buildings • Major present and the future. Cities in developing countries like Iran are facing some of the concern are: motor vehicle congestion and commercial activity - Bank headquarters - Financial firms - urban growth. However, the concern in cities like Sabzevar is that Professional services in general. this growth is far more rapid (especially increasing day by day In Central Business District Secondary Characteristics is: motor vehicle). Like many urban processes the spatial nature of • Large public buildings • Town hall and government these problems is self-evident. In order to solve urban mobility buildings • Specialist shops and high end shops • Small problems, this work aims to clarify urban land use changes of the resident population • Office buildings • High pedestrian CBD in a city. Sabzevar city is selected as the study area, because due to excessive focus of attractive land use, functional movement • Maximum parking restrictions in general. differentiation is developed as a result of rapid urban growth. -

A Generic Classification Scheme for Urban Structure Types

remote sensing Article A Generic Classification Scheme for Urban Structure Types Arthur Lehner * and Thomas Blaschke Department of Geoinformatics—Z_GIS, University of Salzburg, 5020 Salzburg, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-662-8044-7510 Received: 2 December 2018; Accepted: 15 January 2019; Published: 17 January 2019 Abstract: This paper presents a proposal for a generic urban structure type (UST) scheme. Initially developed in the context of urban ecology, the UST approach is increasingly popular in the remote sensing community. However, there is no consistent and standardized UST framework. Until now, the terms land use and certain USTs are often used and described synonymously, or components of structure and use are intermingled. We suggest a generic nomenclature and a respective UST scheme that can be applied worldwide by stakeholders of different disciplines. Based on the insights of a rigorous literature analysis, we formulate a generic structural- and object-based typology, allowing for the generation of hierarchically and terminologically consistent USTs. The developed terminology exclusively focuses on morphology, urban structures and the general exterior appearance of buildings. It builds on the delimitation of spatial objects at several scales and leaves out all social aspects and land use aspects of an urban area. These underlying objects or urban artefacts and their structure- and object-related features, such as texture, patterns, shape, etc. are the core of the hierarchically structured UST scheme. Finally, the authors present a generic framework for the implementation of a remote sensing-based UST classification along with the requirements regarding sensors, data and data types. -

Urban Structure and Land Use

URBAN STRUCTURE AND LAND USE Urban structure is the arrangement of land use in urban areas, in other words, how the land use of a city is set out. Urban planners, economists, and geographers have developed several models that explain where different types of people and businesses tend to exist within the urban setting. Urban structure can also refer to urban spatial structure, which concerns the arrangement of public and private space in cities and the degree of connectivity and accessibility. In essence, there are three model to explain the distribution of social groups within urban areas: . Zonal Model . Sectoral Model . Multiple Nuclei Model ZONAL MODEL: The zonal model also knows as concentric zone model, Burgess model or the CCD model is one of the earliest theoretical models to explain urban social structures. It was created by sociologist Ernest Burgess in 1925. Key (from outside to inside) Commuter zone (outer ring) Residential zone Working class zone Zone of transition Factory zone Central business district (centre) Based on human ecology theory done by Burgess and applied on Chicago, it was the first to give the explanation of distribution of social groups within urban areas. This concentric ring model depicts urban land usage in concentric rings: the Central Business District (or CBD) was in the middle of the model, and the city is expanded in rings with different land uses. It is effectively an urban version of Von Thünen's regional land use model developed a century earlier. It influenced the later development of Homer Hoyt's sector model (1939) and Harris and Ullman's multiple nuclei model (1945). -

Piccadilly Basin Strategic Regeneration Framework

Piccadilly Basin Strategic Regeneration Framework October 2016 1 Contents Executive Summary 3 1 Introduction 9 2 Economic Context 12 3 Strategic Policy and Regeneration Context 19 4 Piccadilly Basin SRF - Site Analysis 31 5 Development and Urban Design Principles 67 6 Phasing and Delivery Strategy 92 2 Executive Summary Piccadilly Basin SRF Opportunity The Piccadilly Basin SRF represents an opportunity to create a Located in a thriving City Centre. best in class City Centre neighbourhood community with a vibrant mix of office, residential, retail and leisure accommodation offering Adjacent to a major transport hub with exception a place to live, work, relax and play; a place that fosters enterprise transport connections. and innovation; and helps to set Manchester apart from its peer cities. This should be provided as part of: Adjacency to the City’s Northern Quarter. a well-designed environment that is well managed, safe, Adjacency to major areas of investment and growth accessible, sustainable and resilient to climate change, a including Ancoats and New Islington and the wider HS2 place where people will want to live and which fosters long masterplan area. term sustainable communities; A critical mass of land ownership and delivery partners a place with a strong identity supported and enhanced by with a proven track record. new development which reinstates and celebrates Piccadilly Basin’s richly layered history and associated assets based The ability to build upon a diverse mix of established around mills and canal infrastructure; and, uses. an extremely well connected neighbourhood in terms of Waterside frontage and heritage assets that add highly legible, high quality pedestrian and cycle connections character and can form the basis of distinctive place- and complementary uses which provide strong functional making connections. -

Where Are People Distributed Within Urban Areas?

410 The Cultural Landscape yards and modern schools. And they were pushed from CBDs KEY ISSUE 2 by high rents that business and retail services were willing to pay and by the dirt, crime, congestion, and poverty that they experienced by living downtown. Where Are People In the twenty-first century, however, the population of many U.S. CBDs has increased. New apartment buildings and town- Distributed Within houses have been constructed, and abandoned warehouses and outdated office buildings have been converted into residential Urban Areas? lofts. Downtown living is especially attractive to people with- ■ out school-age children, either “empty nesters” whose children Models of Urban Structure have left home or young professionals who have not yet had ■ Applying the Models Outside children. These two groups are attracted by the entertainment, North America restaurants, museums, and nightlife that are clustered down- town, and they are not worried about the quality of neighbor- People are not distributed randomly within an urban area. hood schools. They concentrate in particular neighborhoods, depending on their social characteristics. Geographers describe where people with particular characteristics are likely to live within an urban area, and they offer explanations for CBDs Outside why these patterns occur. ■ North America CBDs outside the United States are less dominated by commer- cial considerations. The most prominent structures may be Models of Urban Structure churches and former royal palaces, situated on the most impor- Sociologists, economists, and geographers have developed tant public squares, at road junctions, or on hilltops. Parks in three models to help explain where different types of people the center of European cities often were first laid out as private tend to live in an urban area—the concentric zone, sector, and gardens for aristocratic families and later were opened to the multiple nuclei models.