Homer Hoyt: an Introduction First Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Utility of the Economic Base Method in Calculating Urban Growth Author(S): Homer Hoyt Source: Land Economics, Vol

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System The Utility of the Economic Base Method in Calculating Urban Growth Author(s): Homer Hoyt Source: Land Economics, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Feb., 1961), pp. 51-58 Published by: University of Wisconsin Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3159349 Accessed: 31-08-2015 13:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Wisconsin Press and The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Land Economics. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.186.252.94 on Mon, 31 Aug 2015 13:21:17 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Utility of The Economic Base Method in Calculating Urban Growth By HOMER HOYT* the firstdefinitions of basicand ers.6 It is asserted that the economic base SINCEnon-basic occupations by Haig in as a method is too simple and crude for 1928,1 Nussbaum in 1933,2 my own arti- the purpose of accurately forecasting the cles and reports from 1936 to 1954,3 population of an urban region, chiefly John W. -

RESUME DR. JAMES B. KAU Emeritus Professor And

RESUME DR. JAMES B. KAU Emeritus Professor and former University of Georgia C. Herman and Mary Department of Insurance, Virginia Terry Distinguished Chair Legal Studies and Real Estate in Business Administration, 1988-2010 ADDRESS HOME: 345 St. George Drive OFFICE: Faculty of Real Estate Athens, Georgia 30606 Terry College of Business University of Georgia Athens, Georgia 30602-6255 (706) 542-9110 EDUCATION Ph.D. Economics University of Washington, 1971 M.A. Economics University of Washington, 1969 B.A. Mathematics University of Washington, 1967 HONORS The Pioneer Award, 2014, is the American Real Estate Society recognition of people who are at the end of their career and have made a lasting contribution to real estate education and research. George Bloom Service Award, 2013, in recognition of distinguished service to the American Real Estate and Urban Economic Association. The Graaskamp Award, 2010, is the American Real Estate Society recognition of extraordinary iconolistic thought and/or action throughout a person’s career in the development of a multi-disciplinary philosophy of real estate. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE The Terry Chair Professor of Business, Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, 1988-Present Professor of Real Estate, Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, 1980-1988 Visiting Professor, Graduate School of Management, UCLA, 1988 Visiting Scholar, Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, 1985 Visiting Professor of Finance and Real Estate, University of California-Berkeley, 1984 Visiting Scholar, Federal -

Central Business District Development in a Transition Economy – Case Studies of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, China

Central Business District Development in a Transition Economy – Case Studies of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, China Bo B. S. TANG and Stanley Chi-Wai YEUNG Department of Building and Real Estate, Hong Kong Polytechnic University Weiwen Li Shenzhen University, China Acknowledge This paper is based on the research project funded by the Direct RGC Grant to the Hong Kong Polytechnic University of Hong Kong A-P032 Key words: CBD Development, transition economy, China Abstract Since its implementation of economic reforms and open door policy, China has rapidly transformed itself from a socialist planned economy to socialist market economy. Guangzhou and Shanzhen are earmarked as the pioneering and experimental cities within the network of cities in Pearl River Delta Region in implementing various market reform measures. Taking advantage of its close proximity with Hong Kong and Macau, these two cities have achieved remarkable success in economic strength and become modernized commercial cities. Supported by the growth of tertiary industries such as finance. information technology, business and trading, property development in these two cities has also taken a rapid pace. CBD development can also be identifies. CBD development is a relatively new product within the development process of socialist China. Before the marketization reform, China’s socialist planned economy implied that the state was responsible for resource allocation. There was no room for market adjustment. Commercial retail areas replaced the position of CBD as the urban centres. When China adopted its open door policy and introduced market mechanism, the spatial structure of existing cities has begun to change. Business and trading activities outside the state planning process becomes increasingly important. -

Stephen L Ross

STEPHEN L ROSS Department of Economics, 341 Mansfield Rd, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: 860-486-3533, 959-200-3815 Email: [email protected], Twitter: @SteveRo48195125 EDUCATION Syracuse University, Ph.D., 1994, Economics, Thesis Advisor: John M. Yinger, Fields: Urban, Public. Wright State University, M.A., 1990, Applied Behavioral Science, Thesis Advisor: John P. Blair. University of Kansas, B.S., 1984, Engineering Physics. ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor, Economics Dept., Public Policy Dept. (courtesy), Center for Real Estate and Urban Economic Studies, Urban and Community Studies Program, University of Connecticut, 1994-Present. Department Head, Department of Economics, University of Connecticut, 2015-2016. Director, Urban and Community Studies, University of Connecticut, 2008-2012. Visiting Faculty, Department of Economics, Yale University, fall 2005, fall 2007. OTHER RELEVANT POSITIONS Research Associate, Education Program, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021-Present Associate Editor, Education, Finance and Policy, 2019-Present. Co-editor, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2018-Present. Phillip E. Austin Endowed Chair in Public Policy, University of Connecticut, 2016-2021. Editorial Boards, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2020-Present, Journal of Economic Geography, 2015-Present, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 2014-Present, Journal of Housing Economics, 2011-Present, Journal of Urban Economics, 2009-Present, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2007-Present. Affiliations, Center for Financial Security, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2018-Present, Penn Institute for Urban Research, University of Pennsylvania, 2014-Present, Weimer School of Advanced Studies in Real Estate and Land Economics, Homer Hoyt Institute, 2012-Present, Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Global Working Group, University of Chicago, 2011-Present. -

Models of Urban Growth : Concentric Zones, Sectors, Multiple Nuclei, Explaitative, Syrn Bolic

Models of Urban Growth : Concentric Zones, Sectors, Multiple Nuclei, Explaitative, Syrn bolic 6.1 lntroduction 6.2 Structure of Cities 6.3 Concentric Zone Model . 6.4 Sectors Model 6.5 Multiple Nuclei Model 6.6 Exploitative Model 6.7 Symbolic Approach 6.8 Conclusion 6.9 Further Reading Learning Objectives After studying this unit you should be able to: discuss the structure of cities; describe the concentric zone model of studying the structure of cities; explain the sectors model; , describe the multiple nuclei model; discuss the exploitative model; and explain the symbolic approach to the study of city. 6.1 lntroduction Under the rubric of urban ecological process and theories, you have already learnt about the processes of invasion, succession, concentration, centralisation and segregation which characterise different kinds and dimensions of cities. Here in this unit you will learn further about the different aspects of cities and their formations. As you already know, urban society is defined as a relatively larger, dense, permanent, heterogeneous settlements whose majority of inhabitants are engaged in non-agricultural occupation. The development of such urban society is very much determined by socio - cultural organisation, climate, topography and economic development. The earliest cities of the world originated near river valleys such as early civilization of lndus (Mohenjodaro, Harrappa), Tigris - Eupharates (Lagas Ur, Uruk), Nile (Memphis, Thebes) 5 7 and Hwang Ho (Chen-Chan An Yang). These early development of urban settlements evolved with changing technology and human needs. Trade and commercial activities and settled agriculture were major facilitators; even today these,factors are very much relevant in the growth of a city. -

Compare and Contrast the Concentric, Sector and Multiple Nuclei Models

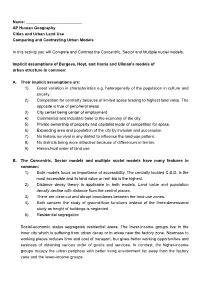

Name: _________________________ AP Human Geography Cities and Urban Land Use Comparing and Contrasting Urban Models In this activity you will Compare and Contrast the Concentric, Sector and Multiple nuclei models. Implicit assumptions of Burgess, Hoyt, and Harris and Ullman’s models of urban structure in common: A. Their implicit assumptions are: 1) Great variation in characteristics e.g. heterogeneity of the population in culture and society. 2) Competition for centrality because of limited space leading to highest land value. The opposite is true of peripheral areas. 3) City center being center of employment. 4) Commercial and industrial base to the economy of the city. 5) Private ownership of property and capitalist mode of competition for space. 6) Expanding area and population of the city by invasion and succession. 7) No historic survival in any district to influence the land-use pattern. 8) No districts being more attractive because of differences in terrain. 9) Hierarchical order of land use. B. The Concentric, Sector models and multiple nuclei models have many features in common: 1) Both models focus on importance of accessibility. The centrally located C.B.D. is the most accessible and its land value or rent-bid is the highest. 2) Distance decay theory is applicable in both models. Land value and population density decline with distance from the central places. 3) There are clear-cut and abrupt boundaries between the land-use zones. 4) Both concern the study of ground-floor functions instead of the three-dimensional study as height of buildings is neglected 5) Residential segregation Social-economic status segregates residential areas. -

THE GREAT CRASH of 2008 Mason Gaffney August 17, 2008

THE GREAT CRASH OF 2008 Mason Gaffney August 17, 2008 This crash is The Big One; it has signs of becoming a Category 5. How do we know? We’ve “been there and done that” so many times before, roughly every 18 years over the last 800 or more. Major wars and, rarely, plagues have broken the rhythm, along with the little ice age, reformation and counter-reformation, political revolutions and reactions, the rise of nation-states, the enclosure movement, the age of exploration, massive European imports of stolen American gold, the scientific and industrial revolutions, the Crusades, Mongol and Turkish invasions, and other upheavals. Yet, the endogenous cycle keeps returning, as soon as we find peace, and economic life returns to its even tenors. What President Warren Harding famously called “normalcy” soon evolved into another boom and a shocking bust, as so often before. Calm and routine prosperity has never been man’s lot for long: it somehow leads to its own downfall, cycle after cycle. Homer Hoyt published his classic 100 Years of Land Values in Chicago, 1833-1933, in December, 1933. He covered in fine detail the 5 major cycles that crested and crashed in 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1926-29. At the end he generalized “The Chicago Real Estate Cycle”, a regular rhythm of boom and bust with the same features in the same sequence. The boom sets us up for the bust. He could have omitted the limiting word “Chicago”, its cycles were synchronized with national waves recorded by other scholars like Arthur H. -

DO STOCK PRICES REALLY REFLECT FUNDAMENTAL VALUES? the CASE of Reits

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DO STOCK PRICES REALLY REFLECT FUNDAMENTAL VALUES? THE CASE OF REITs William M. Gentry Charles M. Jones Christopher J. Mayer Working Paper 10850 http://www.nber.org/papers/w10850 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2004 We thank David Geltner, Joe Gyourko, Peter Linneman, Steve Ott, Todd Sinai and seminar participants at the AREUEA Annual Meeting, the Columbia Business School, the Homer Hoyt Institute, the University of California at Berkeley, the University of Southern California, the University of Wisconsin, and the Wharton School for helpful comments. Dou-Yan Yang, Dimo Pramatarov, and Tobias Muhlhofer provided excellent research assistance. We are especially grateful to Jon Fosheim, Mike Kirby, and Green Street Advisors for providing crucial data used in this study. This paper was previously titled “Deviations between stock price and fundamental value for real estate investment trusts” and “REIT reversion: stock price adjustment to fundamental value.” The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. ©2004 by William M. Gentry, Charles M. Jones, and Christopher J. Mayer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Do Stock Prices Really Reflect Fundamental Values? The Case of REITs William M. Gentry, Charles M. Jones, and Christopher J. Mayer NBER Working Paper No. 10850 October 2004 JEL No. G0, G12 ABSTRACT Real estate investment trust (REIT) stock prices deviate substantially from net asset values (NAV). -

Models of Urban Structure Residential Deterioration and Encroachment by Business and Light Manufacturing

Models of Urban Structure residential deterioration and encroachment by business and light manufacturing. The zone of independent Cities are not simply random collections of buildings and workers homes (3) was primarily occupied by the blue- people. They exhibit functional structure: they are collar (wage-earners, manual laborers) labor force. The spatially organized to perform their functions as places of zone of better residences (4) consisted mainly of the commerce, production, education, and much more. One middle-class. Finally, the commuters zone (5) was the of the most important forces determining where certain suburban ring, consisting mostly of white-collar workers buildings or activities are located within a city deals with who could afford to live further from the CBD. This the price of land. This tends to be the highest in the model was dynamic. As the city grew, the inner zones downtown area and declines as one moves outward from encroached on the outer ones. the center. The United States is the only country in the world in which the majority of the people live in the Remember, the model was developed for American cities suburbs. Even though house prices may be higher in the and had limited applicability elsewhere. It has been suburbs, the land value is lower (a downtown apartment demonstrated that pre-industrial cities, notably in Europe, complex will produce much more revenue per year than a did not at all followed the concentric circles model. For few suburban homes occupying the same amount of instance, in most pre-industrial European cities, the center space). In every other country the majority resides in was much more important than the periphery, notably in either rural or urban areas. -

Using the Urban Landscape Mosaic to Develop and Validate Methods for Assessing the Spatial Distribution of Urban Ecosystem Service Potential

USING THE URBAN LANDSCAPE MOSAIC TO DEVELOP AND VALIDATE METHODS FOR ASSESSING THE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF URBAN ECOSYSTEM SERVICE POTENTIAL Oliver Twanhaw GUNAWAN School of Environment and Life Sciences College of Science and Technology University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, July 2015 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... vii List of Tables .......................................................................................................... xiii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... xvii Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... xviii Abstract .................................................................................................................... xx 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Context of research .......................................................................................... 1 1.2. Ecosystem services in the urban environment .................................................. 2 1.3. Thesis structure ............................................................................................... -

Theories of Urban Growth

THEORIES OF URBAN GROWTH • Although several theories have been developed to explain the dynamics of city growth, all such theories are based upon the operation of five ecological processes of concentration, centralization, invasion and succession and observations based upon it about actual city growth in concrete situations. • However, one can hardly find a theory of an ideal pattern of urban dynamics as growth of particular city depends upon many factors, the basic one being natural location of a city .Nevertheless, one can notice a set of common principles which govern city growth everywhere • The major theories of internal structure of urban settlements have been advanced on the basis of empirical investigations conducted in the Western urban society, particularly in North America and Europe. • . Concentric zone model • Ernest Burgess is the pioneer and his theory on city dynamics which provides the base for the later theorists on the subject. The hypothesis of this theory is that cities grow and develop outwardly in concentric zones. Burgess set out to evolve a theory of dynamics but he arrived at a theory of patterns of city growth which applies to any stage stages of urban development. According to Burgess, an urban area consists of five concentric zones which represent areas of functional differentiation and expand rapidly from the Justness centre. The zones are: • (1) The loop or commercial centre • (2) The zone of transition. • (3) The zone of working class residence • (4) The residential zone of high class apartment buildings. • (5) The commuter's zone. 1. The loop or central business district or commercial centre: • 1. -

Pockets of Poverty: the Long-Term Effects of Redlining

Pockets of Poverty: The Long-Term Effects of Redlining Ian Appel∗ Jordan Nickersony October 2016 This paper studies the long-term effects of redlining policies that restricted access to credit in urban communities. For empirical identification, we use a regression discontinuity design that exploits boundaries from maps created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1940. We find that \redlined" neighborhoods have 4.8% lower home prices in 1990 relative to adjacent areas. This finding is robust to the exclusion of boundaries that coincide with the physical features of cities (e.g., rivers, landmarks). Moreover, we show that housing characteristics varied smoothly at the boundaries when the maps were created. Evidence suggests lower property values may be driven by negative externalities associated with fewer owner-occupied homes and more vacant structures. Overall, our results indicate the effects of discriminatory credit rationing can persist decades after such practices are formally discontinued. JEL Classification: E5, N3, R2, R31 Keywords: Redlining, Credit Rationing, Household Finance ∗Boston College, Carroll School of Management, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467; telephone: (617)552-1459. E-mail: [email protected] yBoston College, Carroll School of Management, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467; telephone: (617)552-2847. E-mail: [email protected] History is rife with examples of discriminatory practices intended to limit access to fi- nance. A particularly notorious case was credit rationing in US housing markets. Throughout much of the 20th century, both private lenders and federal agencies limited the availability of mortgage credit to racial and ethnic minorities. Such practices, which potentially reflect the preferences of intermediaries (Becker(1957)) or information asymmetry (Arrow(1973); Phelps(1972)), were eventually outlawed in the 1960s.