DO STOCK PRICES REALLY REFLECT FUNDAMENTAL VALUES? the CASE of Reits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Utility of the Economic Base Method in Calculating Urban Growth Author(S): Homer Hoyt Source: Land Economics, Vol

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System The Utility of the Economic Base Method in Calculating Urban Growth Author(s): Homer Hoyt Source: Land Economics, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Feb., 1961), pp. 51-58 Published by: University of Wisconsin Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3159349 Accessed: 31-08-2015 13:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Wisconsin Press and The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Land Economics. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.186.252.94 on Mon, 31 Aug 2015 13:21:17 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Utility of The Economic Base Method in Calculating Urban Growth By HOMER HOYT* the firstdefinitions of basicand ers.6 It is asserted that the economic base SINCEnon-basic occupations by Haig in as a method is too simple and crude for 1928,1 Nussbaum in 1933,2 my own arti- the purpose of accurately forecasting the cles and reports from 1936 to 1954,3 population of an urban region, chiefly John W. -

RESUME DR. JAMES B. KAU Emeritus Professor And

RESUME DR. JAMES B. KAU Emeritus Professor and former University of Georgia C. Herman and Mary Department of Insurance, Virginia Terry Distinguished Chair Legal Studies and Real Estate in Business Administration, 1988-2010 ADDRESS HOME: 345 St. George Drive OFFICE: Faculty of Real Estate Athens, Georgia 30606 Terry College of Business University of Georgia Athens, Georgia 30602-6255 (706) 542-9110 EDUCATION Ph.D. Economics University of Washington, 1971 M.A. Economics University of Washington, 1969 B.A. Mathematics University of Washington, 1967 HONORS The Pioneer Award, 2014, is the American Real Estate Society recognition of people who are at the end of their career and have made a lasting contribution to real estate education and research. George Bloom Service Award, 2013, in recognition of distinguished service to the American Real Estate and Urban Economic Association. The Graaskamp Award, 2010, is the American Real Estate Society recognition of extraordinary iconolistic thought and/or action throughout a person’s career in the development of a multi-disciplinary philosophy of real estate. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE The Terry Chair Professor of Business, Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, 1988-Present Professor of Real Estate, Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, 1980-1988 Visiting Professor, Graduate School of Management, UCLA, 1988 Visiting Scholar, Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, 1985 Visiting Professor of Finance and Real Estate, University of California-Berkeley, 1984 Visiting Scholar, Federal -

Stephen L Ross

STEPHEN L ROSS Department of Economics, 341 Mansfield Rd, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: 860-486-3533, 959-200-3815 Email: [email protected], Twitter: @SteveRo48195125 EDUCATION Syracuse University, Ph.D., 1994, Economics, Thesis Advisor: John M. Yinger, Fields: Urban, Public. Wright State University, M.A., 1990, Applied Behavioral Science, Thesis Advisor: John P. Blair. University of Kansas, B.S., 1984, Engineering Physics. ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor, Economics Dept., Public Policy Dept. (courtesy), Center for Real Estate and Urban Economic Studies, Urban and Community Studies Program, University of Connecticut, 1994-Present. Department Head, Department of Economics, University of Connecticut, 2015-2016. Director, Urban and Community Studies, University of Connecticut, 2008-2012. Visiting Faculty, Department of Economics, Yale University, fall 2005, fall 2007. OTHER RELEVANT POSITIONS Research Associate, Education Program, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021-Present Associate Editor, Education, Finance and Policy, 2019-Present. Co-editor, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2018-Present. Phillip E. Austin Endowed Chair in Public Policy, University of Connecticut, 2016-2021. Editorial Boards, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2020-Present, Journal of Economic Geography, 2015-Present, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 2014-Present, Journal of Housing Economics, 2011-Present, Journal of Urban Economics, 2009-Present, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2007-Present. Affiliations, Center for Financial Security, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2018-Present, Penn Institute for Urban Research, University of Pennsylvania, 2014-Present, Weimer School of Advanced Studies in Real Estate and Land Economics, Homer Hoyt Institute, 2012-Present, Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Global Working Group, University of Chicago, 2011-Present. -

THE GREAT CRASH of 2008 Mason Gaffney August 17, 2008

THE GREAT CRASH OF 2008 Mason Gaffney August 17, 2008 This crash is The Big One; it has signs of becoming a Category 5. How do we know? We’ve “been there and done that” so many times before, roughly every 18 years over the last 800 or more. Major wars and, rarely, plagues have broken the rhythm, along with the little ice age, reformation and counter-reformation, political revolutions and reactions, the rise of nation-states, the enclosure movement, the age of exploration, massive European imports of stolen American gold, the scientific and industrial revolutions, the Crusades, Mongol and Turkish invasions, and other upheavals. Yet, the endogenous cycle keeps returning, as soon as we find peace, and economic life returns to its even tenors. What President Warren Harding famously called “normalcy” soon evolved into another boom and a shocking bust, as so often before. Calm and routine prosperity has never been man’s lot for long: it somehow leads to its own downfall, cycle after cycle. Homer Hoyt published his classic 100 Years of Land Values in Chicago, 1833-1933, in December, 1933. He covered in fine detail the 5 major cycles that crested and crashed in 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1926-29. At the end he generalized “The Chicago Real Estate Cycle”, a regular rhythm of boom and bust with the same features in the same sequence. The boom sets us up for the bust. He could have omitted the limiting word “Chicago”, its cycles were synchronized with national waves recorded by other scholars like Arthur H. -

Theories of Urban Growth

THEORIES OF URBAN GROWTH • Although several theories have been developed to explain the dynamics of city growth, all such theories are based upon the operation of five ecological processes of concentration, centralization, invasion and succession and observations based upon it about actual city growth in concrete situations. • However, one can hardly find a theory of an ideal pattern of urban dynamics as growth of particular city depends upon many factors, the basic one being natural location of a city .Nevertheless, one can notice a set of common principles which govern city growth everywhere • The major theories of internal structure of urban settlements have been advanced on the basis of empirical investigations conducted in the Western urban society, particularly in North America and Europe. • . Concentric zone model • Ernest Burgess is the pioneer and his theory on city dynamics which provides the base for the later theorists on the subject. The hypothesis of this theory is that cities grow and develop outwardly in concentric zones. Burgess set out to evolve a theory of dynamics but he arrived at a theory of patterns of city growth which applies to any stage stages of urban development. According to Burgess, an urban area consists of five concentric zones which represent areas of functional differentiation and expand rapidly from the Justness centre. The zones are: • (1) The loop or commercial centre • (2) The zone of transition. • (3) The zone of working class residence • (4) The residential zone of high class apartment buildings. • (5) The commuter's zone. 1. The loop or central business district or commercial centre: • 1. -

Pockets of Poverty: the Long-Term Effects of Redlining

Pockets of Poverty: The Long-Term Effects of Redlining Ian Appel∗ Jordan Nickersony October 2016 This paper studies the long-term effects of redlining policies that restricted access to credit in urban communities. For empirical identification, we use a regression discontinuity design that exploits boundaries from maps created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1940. We find that \redlined" neighborhoods have 4.8% lower home prices in 1990 relative to adjacent areas. This finding is robust to the exclusion of boundaries that coincide with the physical features of cities (e.g., rivers, landmarks). Moreover, we show that housing characteristics varied smoothly at the boundaries when the maps were created. Evidence suggests lower property values may be driven by negative externalities associated with fewer owner-occupied homes and more vacant structures. Overall, our results indicate the effects of discriminatory credit rationing can persist decades after such practices are formally discontinued. JEL Classification: E5, N3, R2, R31 Keywords: Redlining, Credit Rationing, Household Finance ∗Boston College, Carroll School of Management, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467; telephone: (617)552-1459. E-mail: [email protected] yBoston College, Carroll School of Management, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467; telephone: (617)552-2847. E-mail: [email protected] History is rife with examples of discriminatory practices intended to limit access to fi- nance. A particularly notorious case was credit rationing in US housing markets. Throughout much of the 20th century, both private lenders and federal agencies limited the availability of mortgage credit to racial and ethnic minorities. Such practices, which potentially reflect the preferences of intermediaries (Becker(1957)) or information asymmetry (Arrow(1973); Phelps(1972)), were eventually outlawed in the 1960s. -

Kerry Dean Vandell Professor Emeritus of Economics and Public Policy and Former Director, Center for Real Estate the Paul Merage

Kerry Dean Vandell Professor Emeritus of Economics and Public Policy and former Director, Center for Real Estate The Paul Merage School of Business Dean's Professor Emeritus of Law, School of Law (Courtesy Appointment) Professor Emeritus of Policy, Planning, and Design, School of Social Ecology (Courtesy Appointment) University of California – Irvine July 2017 Office Address Home Address The Paul Merage School of Business 2658 Victoria Drive Room 205 Building SB2 Laguna Beach. CA 92651 University of California-Irvine Irvine, CA 92697-3125 Phone: (949) 824-1985 Phone: (949) 715-1333 Cell: (949) 981-5424 Fax: (949) 824-9308 e-mail: [email protected] Personal Data Date of Birth: January 8, 1947 Married: Deborah Lowe Vandell, Professor, School of Education, University of California - Irvine Two children - Colin Buckner born October 4, 1979, Ashley Elizabeth born March 9, 1985 Education Ph.D. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1977 (Urban Studies and Planning) Dissertation: Alternative Mortgage Instruments: Their Distributional Effects on Homeownership, Housing Consumption, and the Use of Mortgage Credit Chairman: Arthur P. Solomon M.C.P. Harvard University, 1973 (City and Regional Planning) B.A./M.M.E. Rice University, 1970 (Mechanical Engineering) Honors and Awards 2017 Dean's Professor Emeritus of Economics and Public Policy (Real Estate) 2017 Society of Fellows, Asian Real Estate Society (invited) 2010-13 Distinguished Academic Fellow, NAIOP: The Commercial Real Estate Development Association (invited) 2009-13 Community Development -

Redlining and the Homeowners' Loan Corporation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (City and Regional Planning) Department of City and Regional Planning 5-1-2003 Redlining and the Homeowners' Loan Corporation Amy E. Hillier University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cplan_papers Part of the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Hillier, Amy E., "Redlining and the Homeowners' Loan Corporation" (2003). Departmental Papers (City and Regional Planning). 3. https://repository.upenn.edu/cplan_papers/3 Copyright Sage Publications. Postprint version. Published in Journal of Urban History, Volume 29, Issue 4, 2003, pages 394-420. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cplan_papers/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Redlining and the Homeowners' Loan Corporation Abstract This article analyzes the impact of the residential security maps created by the Home Owners’Loan Corporation (HOLC) during the 1930s on residential mortgages in Philadelphia. Researchers have consistently argued that HOLC caused redlining and disinvestment in U.S. cities by sharing its color- coded maps. Geographic information systems and spatial statistical models were used to analyze address-level mortgage data from Philadelphia to determine if areas with worse grades actually had less access to residential mortgage credit as a result. Findings indicate that the grades on HOLC’s map do not explain differences in lending patterns with the exception of interest rates, which were higher in areas colored red. Archival material and journal articles from the 1930s also reveal that lenders were avoiding areas colored red before HOLC made its maps, that HOLC’s maps were not widely distributed, and that lenders had other sources of information about real estate risk levels. -

Hoyt Sector Model: AP Human Geography Crash Course

Hoyt Sector Model: AP Human Geography Crash Course Are you a city person? Whether you like it or not, you are probably like more than half of the population of the United States and live either in a city or close enough to quickly travel to one. Cities are growing much faster than rural areas, and it is important for you to learn about the dynamics of urban geography. There are several classic models used to understand and explain the internal structures of cities and urban areas, and we are going to learn about the Hoyt Sector Model in this AP Human Geography study guide. Nature of the City Cities are at the center of every advanced society and act as the hub of economic, social and political activities in that area. They have a variety shapes and functions, and their geography impacts the daily lives of those who live in the city and surrounding areas. All cities provide their residents a variety of services and functions: shopping, manufacturing, transportation, education, medical, and protective services. Cities evolved over time, and if a city had favorable factors (agriculture, access to water, trade, defense), its population increased. This led to urbanization (rapid growth, and migration to large cities). This increase in urban population resulted in rapid expansion of the city and greater urbanization of the society. After the conclusion of World War II, North America experienced rapid urbanization. There was a need for housing outside of the core urban areas due to growing population and demand. The result was the suburbanization of our society. -

Human Ecology and Its Influence in Urban Theory and Housing Policy

Essay Human Ecology and Its Influence in Urban Theory and Housing Policy in the United States Ivis García City and Metropolitan Planning, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 60608, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 February 2019; Accepted: 18 May 2019; Published: 22 May 2019 Abstract: Human ecology, a stream of planning, was developed by Park, Burgess, and Hoyt. This theoretical model emphasized mobility and assimilation as natural paths to housing. This essay offers an analysis of its influence on urban theory and policymaking in the United States. Using planning-specific analyses, the author interrogates the relationships between structural and ecological interpretations of urban change within early planning theory. A particular focus is given to housing policies and models such as tipping point, segregation, and gentrification. These human ecological interpretations inspired and shaped urban renewal and redlining practices, along with public and affordable housing in the United States. The essay concludes with a criticism of the ecological ideas of spontaneous order and the claims of naturally balancing economic systems and conceptions of personal responsibility and choice. Keywords: Chicago school; neighborhood change; urban renewal; redlining; tipping point; segregation; gentrification; personal responsibility 1. Introduction Urban scholars can benefit from the recapitulation of human ecology to understand how it has shaped public policies and the built environment. More specifically,how this way of thinking has affected the metamorphoses of neighborhoods over time. The ideas of ecological order within cities provide critical insights into modern presumptions within urban studies. The analyses of human ecologists delve into ethnic and racial conflicts. They also shaped segregation and processes of assimilation. -

Urban Structure and Land Use

URBAN STRUCTURE AND LAND USE Urban structure is the arrangement of land use in urban areas, in other words, how the land use of a city is set out. Urban planners, economists, and geographers have developed several models that explain where different types of people and businesses tend to exist within the urban setting. Urban structure can also refer to urban spatial structure, which concerns the arrangement of public and private space in cities and the degree of connectivity and accessibility. In essence, there are three model to explain the distribution of social groups within urban areas: . Zonal Model . Sectoral Model . Multiple Nuclei Model ZONAL MODEL: The zonal model also knows as concentric zone model, Burgess model or the CCD model is one of the earliest theoretical models to explain urban social structures. It was created by sociologist Ernest Burgess in 1925. Key (from outside to inside) Commuter zone (outer ring) Residential zone Working class zone Zone of transition Factory zone Central business district (centre) Based on human ecology theory done by Burgess and applied on Chicago, it was the first to give the explanation of distribution of social groups within urban areas. This concentric ring model depicts urban land usage in concentric rings: the Central Business District (or CBD) was in the middle of the model, and the city is expanded in rings with different land uses. It is effectively an urban version of Von Thünen's regional land use model developed a century earlier. It influenced the later development of Homer Hoyt's sector model (1939) and Harris and Ullman's multiple nuclei model (1945). -

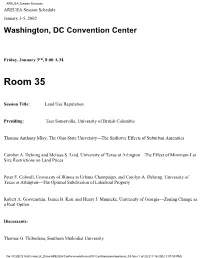

AREUEA Session Schedule AREUEA Session Schedule January 3-5, 2002 Washington, DC Convention Center

AREUEA Session Schedule AREUEA Session Schedule January 3-5, 2002 Washington, DC Convention Center Friday, January 3rd, 8:00 A.M. Room 35 Session Title: Land Use Regulation Presiding: Tsur Somerville, University of British Columbia Thomas Anthony Mlay, The Ohio State University—The Spillover Effects of Suburban Amenities Carolyn A. Dehring and Melissa S. Lind, University of Texas at Arlington—The Effect of Minimum-Lot Size Restrictions on Land Prices Peter F. Colwell, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, and Carolyn A. Dehring, University of Texas at Arlington—The Optimal Subdivision of Lakefront Property Robert A. Grovenstein, James B. Kau, and Henry J. Munneke, University of Georgia—Zoning Change as a Real Option Discussants: Thomas G. Thibodeau, Southern Methodist University file:///C|/BCS Val/Center_K_Drive/AREUEA/Conferences/Annual/03 Conf/sessions/sessions_03.htm (1 of 23) [11/18/2002 3:07:59 PM] AREUEA Session Schedule Yuming Fu, National University of Singapore Daniel P. McMillen, University of Illinois at Chicago Paul Childs, University of Kentucky Room 36 Session Title: Rental Housing Markets Presiding: Frank Nothaft, Freddie Mac Edgar O. Olsen, University of Virginia—The Low Income Housing Tax Credit: An Assessment Stephen Malpezzi, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Henry O. Pollakowski, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Tammie X. Simmons, Lehigh University—The Distribution of Rent Changes within a Market, and Implications for Second Generation Rent Control Mark D. Shroder, and Jennifer A. Stoloff, U.S. Department