AIHRC-UNAMA Joint Monitoring of Political Rights, Presidential And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province by Paul Fishstein ©2012 Feinstein International Center

AUGUST 2012 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice BRIEFING NOTE: Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province by Paul Fishstein ©2012 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image fi les from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 114 Curtis Street Somerville, MA 02144 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fi c.tufts.edu 2 Feinstein International Center Contents I. Summary . 4 II. Study Background . 5 III. Uruzgan Province . 6 A. Geography . 6 B. Short political history of Uruzgan Province . 6 C. The international aid, military, and diplomatic presence in Uruzgan . 7 IV. Findings . .10 A. Confl uence of governance and ethnic factors . .10 B. International military forces . .11 C. Poor distribution and corruption in aid projects . .12 D. Poverty and unemployment . .13 E. Destabilizing effects of aid projects . 14 F. Winning hearts and minds? . .15 V. Final Thoughts and Looking Ahead . .17 Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province 3 I. SUMMARY esearch in Uruzgan suggests that insecurity is largely the result of the failure Rof governance, which has exacerbated traditional tribal rivalries. -

The ANSO Report (16-30 September 2010)

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 58 16-30 September 2010 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-7 The impact of the elections and Zabul while Ghazni of civilian casualties are 7-9 Western Region upon CENTRAL was lim- and Kandahar remained counter-productive to Northern Region 10-15 ited. Security forces claim extremely volatile. With AOG aims. Rather it is a that this calm was the result major operations now un- testament to AOG opera- Southern Region 16-20 of effective preventative derway in various parts of tional capacity which al- Eastern Region 20-23 measures, though this is Kandahar, movements of lowed them to achieve a unlikely the full cause. An IDPs are now taking place, maximum of effect 24 ANSO Info Page AOG attributed NGO ‘catch originating from the dis- (particularly on perceptions and release’ abduction in Ka- tricts of Zhari and Ar- of insecurity) for a mini- bul resulted from a case of ghandab into Kandahar mum of risk. YOU NEED TO KNOW mistaken identity. City. The operations are In the WEST, Badghis was The pace of NGO incidents unlikely to translate into the most affected by the • NGO abductions country- lasting security as AOG wide in the NORTH continues onset of the elections cycle, with abductions reported seem to have already recording a three fold in- • Ongoing destabilization of from Faryab and Baghlan. -

Commission Regulation (Ec)

12.3.2008EN Official Journal of the European Union L 68/11 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 220/2008 of 11 March 2008 amending for the 93rd time Council Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with Usama bin Laden, the Al-Qaida network and the Taliban THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (2) On 1 February 2008, the Sanctions Committee of the United Nations Security Council decided to amend the Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European list of persons, groups and entities to whom the freezing Community, of funds and economic resources should apply. Annex I should therefore be amended accordingly, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with Usama bin Laden, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: the Al-Qaida network and the Taliban, and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 467/2001 prohibiting the export of certain goods and services to Afghanistan, strengthening the flight ban Article 1 and extending the freeze of funds and other financial resources 1 in respect of the Taliban of Afghanistan ( ), and in particular Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 is hereby amended as Article 7(1), first indent, thereof, set out in the Annex to this Regulation. Whereas: Article 2 (1) Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 lists the persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of This Regulation shall enter into force on the day following that funds and economic resources under that Regulation. -

Contamination Status of Districts in Afghanistan

C O N T A M I N A T I O N S T A T U S O F D I S T R I C T S I N A F G H A N I S T A N ? ? ? ? ? ? ? As of 31st March 2019 ? ? ? ? ? T A J I K I S T A N ? ? ? ? ? ? ? U Z B E K I S T A N ? Shaki Darwazbala Darwaz ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? K? uf Ab N Khwahan A Raghistan Shighnan ? T Darqad Yawan ? Yangi Shahri Qala Kohistan ? S ? Buzurg ? Khwaja Chah Ab Bahawuddin Kham Shortepa Yaftal Sufla Wakhan I Qarqin ? Dashti ? ? Arghanj ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Ab ? ? ? Qala ? ? ? ? ? Khani ? ? Fayzabad Khaw ? Imam Sahib ? ? ? N Mangajek Kaldar ? ? Chahar !. ? ? ? ? ? Shahada ? ? ? ? ? ? Khwaja Du Koh ? ? Dawlatabad Argo Faizabad ? Mardyan Dashte ? ? ? Bagh ? ? ? ? ? ? ? C H I N A Qurghan ? Takhar E ? Khwaja ? ? Baharak ? Rustaq ? Archi ? ? ? Hazar ? ? Badakhs han Nahri ? Aqcha Ghar ? Andkhoy ? Kunduz ? ? Sumu? ch Khash ? ? Shahi ? ? ? ? ? Balkh ? Baharak M ? Jawzjan Qalay-I- Zal ? ? Darayim Chahar Khulm Is hkashiem ? ? ? ? Kunduz ? Kalfagan Qaramqol Khaniqa ? ? ? ? ? ? Bolak ? Kishim ? Warduj ? Jurm ? ? ? !. ? Mazar-e Sharif ? !. ? ? ? ? ? ? K ? ? ? ? ? ? Taloqa? n ? ? Taluqan She be rg han ? !. ? ? ? ? ? ? Tashkan ? ? ? ? !. ? ? ? ? ? ? Dihdadi ? ? ? Marmul ? ? ? Chahar Dara ? ? ? Fayzabad ? ? Kunduz ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? R ? Bangi Khanabad ? ? Tagab Namak ? Aliabad ? Chimtal ? Dawlatabad ? ? (Kishmi Feroz ? Hazrati ? ? Chal Shibirghan ? ? Ab ? Farkhar Yamgan ? ? ? ? ? U Sari Pul Balkh Nakhchir Su? ltan Bala) Zebak ? ? Chahar ? (Girwan) ? Baghlani ? Ishkamish ? ? ? ? ? ? Kint ? ? ? ? ? ? Sholgara ? ? ? ? ? -

Financial Intelligence Unit Claim No. Cv 2018

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO FINANCIAL INTELLIGENCE UNIT MINISTRY OF FINANCE APPENDIX LISTING OF COURT ORDERS ISSUED BY THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO UNDER SECTION 22B (3) ANTI-TERRORISM ACT, CH. 12:07 CLAIM NO. CV 2018 - 04598: BETWEEN THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Claimant AND 1. FAIZ; 2. ABDUL BAQI also known as BASIR also known as AWAL SHAH also known as ABDUL BAQI; 3. MOHAMMAD JAWAD also known as WAZIRI; 4. JALALUDDIN also known as HAQQANI also known as JALALUDDIN HAQANI also known as JALLALOUDDIN HAQQANI also known as JALLALOUDDINE HAQANI; 5. MOHAMMAD IBRAHIM also known as OMARI also known as IBRAHIM HAQQANI; 6. DIN MOHAMMAD also known as HANIF also known as QARI DIN MOHAMMAD also known as IADENA MOHAMMAD; 7. HAMDULLAH also known as NOMANI; 8. QUDRATULLAH also known as JAMAL also known as HAJI SAHIB; 9. ABDUL RAHMAN also known as AHMAD also known as HOTTAK also known as HOTTAK SAHIB; 10. ABDULHAI also known as MOTMAEN also known as ABDUL HAQ (son of M. Anwar Khan); 11. MOHAMMAD YAQOUB; 12. ABDUL RAZAQ also known as AKHUND also known as LALA AKHUND; 13. SAYED also known as MOHAMMAD also known as AZIM also known as AGHA also known as SAYED MOHAMMAD AZIM AGHA also known as AGHA SAHEB; 14. NOORUDDIN also known as TURABI also known as MUHAMMAD also known as QASIM also known as NOOR UD DIN TURABI also known as HAJI KARIM; 15. MOHAMMAD ESSA also known as AKHUND; 16. MOHAMMAD AZAM also known as ELMI also known as MUHAMMAD AZAMI; 17. -

Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2012 Nr

946.222.21 Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2012 Nr. 155 ausgegeben am 1. Juni 2012 Verordnung vom 29. Mai 2012 betreffend die Abänderung der Verordnung über Massnahmen gegenüber Personen und Organisationen mit Verbindungen zu den Taliban Aufgrund von Art. 2 des Gesetzes vom 10. Dezember 2008 über die Durchsetzung internationaler Sanktionen (ISG), LGBl. 2009 Nr. 41, unter Einbezug der aufgrund des Zollvertrages anwendbaren schweizeri- schen Rechtsvorschriften und in Ausführung der Resolutionen 1452 (2002) vom 20. Dezember 2002, 1735 (2006) vom 22. Dezember 2006 und 1988 (2011) vom 17. Juni 2011 des Sicherheitsrates der Vereinten Nationen verordnet die Regierung: I. Abänderung bisherigen Rechts Die Verordnung vom 4. Oktober 2011 über Massnahmen gegenüber Personen und Organisationen mit Verbindungen zu den Taliban, LGBl. 2011 Nr. 464, in der geltenden Fassung, wird wie folgt abgeändert: 2 Anhang Bst. A Ziff. 23, 76, 103, 114 und 124 23. TI.A.22.01. Name: 1: UBAIDULLAH 2: AKHUND 3: YAR MOHAMMAD AKHUND 4: na Title: a) Mullah b) Hadji c) Maulavi Designation: Minister of Defence under the Taliban regime DOB: a) Approximately 1968 b) 1969 POB: a) Sangisar village, Panjwai District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan b) Arghandab District, Kandahar Pro- vince, Afghanistan c) Nalgham area, Zheray District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: a) Obaidullah Ak- hund b) Obaid Ullah Akhund Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationa- lity: Afghan Passport no.: na National identification no.: na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. 2001 (amended on 3 Sep. 2003, 18 Jul. 2007, 21 Sep. 2007, 29 Nov. 2011, 18 May 2012) Other information: He was one of the deputies of Mullah Moham- med Omar (TI.0.4.01) and a member of the Taliban's Supreme Council, in charge of military operations. -

"A New Stage of the Afghan Crisis and Tajikistan's Security"

VALDAI DISCUSSION CLUB REPORT www.valdaiclub.com A NEW STAGE OF THE AFGHAN CRISIS AND TAJIKISTAN’S SECURITY Akbarsho Iskandarov, Kosimsho Iskandarov, Ivan Safranchuk MOSCOW, AUGUST 2016 Authors Akbarsho Iskandarov Doctor of Political Science, Deputy Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Acting President of the Republic of Tajikistan (1990–1992); Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Tajikistan; Chief Research Fellow of A. Bahovaddinov Institute of Philosophy, Political Science and Law of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Tajikistan Kosimsho Iskandarov Doctor of Historical Science; Head of the Department of Iran and Afghanistan of the Rudaki Institute of Language, Literature, Oriental and Written Heritage of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Tajikistan Ivan Safranchuk PhD in Political Science; associate professor of the Department of Global Political Processes of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO-University) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia; member of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy The views and opinions expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Contents The growth of instability in northern Afghanistan and its causes ....................................................................3 Anti-government elements (AGE) in Afghan provinces bordering on Tajikistan .............................................5 Threats to Central Asian countries ........................................................................................................................7 Tajikistan’s approaches to defending itself from threats in the Afghan sector ........................................... 10 A NEW STAGE OF THE AFGHAN CRISIS AND TAJIKISTAN’S SECURITY The general situation in Afghanistan after two weeks of fierce fighting and not has been deteriorating during the last few before AGE carried out an orderly retreat. -

The Politics of Disarmament and Rearmament in Afghanistan

[PEACEW RKS [ THE POLITICS OF DISARMAMENT AND REARMAMENT IN AFGHANISTAN Deedee Derksen ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines why internationally funded programs to disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate militias since 2001 have not made Afghanistan more secure and why its society has instead become more militarized. Supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) as part of its broader program of study on the intersection of political, economic, and conflict dynamics in Afghanistan, the report is based on some 250 interviews with Afghan and Western officials, tribal leaders, villagers, Afghan National Security Force and militia commanders, and insurgent commanders and fighters, conducted primarily between 2011 and 2014. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Deedee Derksen has conducted research into Afghan militias since 2006. A former correspondent for the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant, she has since 2011 pursued a PhD on the politics of disarmament and rearmament of militias at the War Studies Department of King’s College London. She is grateful to Patricia Gossman, Anatol Lieven, Mike Martin, Joanna Nathan, Scott Smith, and several anonymous reviewers for their comments and to everyone who agreed to be interviewed or helped in other ways. Cover photo: Former Taliban fighters line up to handover their rifles to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremony at the pro- vincial governor’s compound. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. j. g. Joe Painter/RELEASED). Defense video and imagery dis- tribution system. The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. -

Left in the Dark

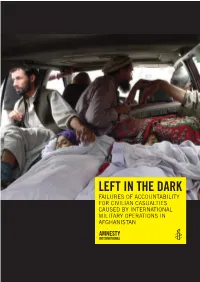

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Afghanistan Earthquake International Organization for Migration

AFGHANISTAN EARTHQUAKE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION SITUATION REPORT 30 October 2015 A girl and her infant brother outside their damaged home in Jurm district, the earthquake's epicenter Highlights © IOM 2015 A 7.5 magnitude earthquake centred The Afghan government estimates IOM has so far completed in northeastern Afghanistan struck on 26 that approximately 6,900 families have assessments in 40 districts, and aid October, causing significant damage and been affected by the earthquake, with distributions are underway for affected casualties across Afghanistan, Pakistan 84 individuals killed and 394 injured. This families in several provinces. and India. estimate is subject to change as more areas are accessed. Situation Overview A 7.5 magnitude earthquake centered in Jurm district in northeastern Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province struck on the afternoon of 26 October, and was felt across the region. Initial reports indicate damaged homes and potential casualties across northern, central and eastern Afghanistan, impacting 13 provinces (102 districts) in total. Badakhshan, Nangarhar, Kunar and Nooristan provinces are the most affected. Approximately 6,900 families are estimated to have been affected by the earthquake, with 84 individuals killed and 394 injured. Assessments have been completed in 40 districts and the distribution of relief items is underway for eligible families. IOM distributed relief items to 175 families in Kunar and Laghman provinces on 30 October. Assessments are ongoing, with the majority expected to conclude by 1 November. The main needs of the affected population are basic household supplies, blankets, tents, hygiene kits and shelters for those whose houses have been completely destroyed. Access in some of the affected areas remains a challenge due to difficult terrain and security concerns. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan.