Northwich Archaeological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of the Parish Council

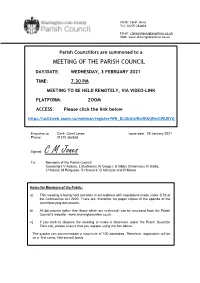

Clerk: Carol Jones Tel: 01270 262636 Email: [email protected] Web: www.shavingtononline.co.uk Parish Councillors are summoned to a MEETING OF THE PARISH COUNCIL DAY/DATE: WEDNESDAY, 3 FEBRUARY 2021 TIME: 7.30 PM MEETING TO BE HELD REMOTELY, VIA VIDEO-LINK PLATFORM: ZOOM ACCESS: Please click the link below. https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_DLGbiCxIRwSKhQNwGWUXYQ Enquiries to: Clerk: Carol Jones Issue date: 29 January 2021 Phone: 01270 262636 Signed: C M Jones To: Members of the Parish Council Councillors V Adams, L Buchanan, N Cooper, B Gibbs (Chairman), K Gibbs, J Hassall, M Ferguson, R Hancock, G McIntyre and R Moore Notes for Members of the Public: a) This meeting is being held remotely in accordance with regulations made under S.78 of the Coronavirus Act 2020. There are, therefore, no paper copies of the agenda or the accompanying documents. b) All documents (other than those which are restricted) can be accessed from the Parish Council’s website - www.shavingtononline.co.uk. c) If you wish to observe the meeting or make a statement under the Public Question Time slot, please ensure that you register using the link above. The system can accommodate a maximum of 100 attendees. Therefore, registration will be on a ‘first come, first served’ basis. Shavington-cum-Gresty Parish Council Agenda – (Meeting – 3 February 2021) A G E N D A 1 APOLOGIES 2 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS Members to declare any (a) disclosable pecuniary interest; (b) personal interest; or (c) prejudicial interest which they have in any item of business on the agenda, the nature of that interest, and in respect of disclosable interests and prejudicial interests, to withdraw from the meeting prior to the discussion of that item. -

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of CHESHIRE WEST and CHESTER Draft Recommendations For

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF CHESHIRE WEST AND CHESTER Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of Cheshire West and Chester August 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 ANTROBUS CP This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. WHITLEY CP SUTTON WEAVER CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information NETHERPOOL applied as part of this review. DUTTON MARBURY ASTON CP GREAT WILLASTON WESTMINSTER CP FRODSHAM BUDWORTH CP & THORNTON COMBERBACH NESTON CP CP INCE LITTLE CP LEIGH CP MARSTON LEDSHAM GREAT OVERPOOL NESTON & SUTTON CP & MANOR & GRANGE HELSBY ANDERTON PARKGATE WITH WINCHAM MARBURY CP WOLVERHAM HELSBY ACTON CP ELTON CP S BRIDGE CP T WHITBY KINGSLEY LOSTOCK R CP BARNTON & A GROVES LEDSHAM CP GRALAM CP S W LITTLE CP U CP B T E STANNEY CP T O R R N Y CROWTON WHITBY NORTHWICH CP G NORTHWICH HEATH WINNINGTON THORNTON-LE-MOORS D WITTON U ALVANLEY WEAVERHAM STOAK CP A N NORTHWICH NETHER N H CP CP F CAPENHURST CP D A WEAVER & CP PEOVER CP H M CP - CUDDINGTON A O D PUDDINGTON P N S C RUDHEATH - CP F T O H R E NORLEY RUDHEATH LACH CROUGHTON D - H NORTHWICH B CP CP DENNIS CP SAUGHALL & L CP ELTON & C I MANLEY -

The Cheshire West and Chester (Electoral Changes) Order 2018

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 59(9) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009; draft to lie for forty days pursuant to section 6(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946, during which period either House of Parliament may resolve that the Order be not made. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2018 No. LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Cheshire West and Chester (Electoral Changes) Order 2018 Made - - - - *** Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009( a) (“the Act”) the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated March 2018 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the borough of Cheshire West and Chester. The Commission has decided to give effect to the recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before Parliament and a period of forty days has expired since the day on which it was laid and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act. Citation, commencement and application 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Cheshire West and Chester (Electoral Changes) Order 2018. (2) This article and article 2 come into force on the day after the day on which this Order is made. (3) Articles 3 and 4 come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on the day after the day on which this Order is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors( c) in 2019. -

The Magazine of Christleton High School Autumn/Winter Term 2014 2 Christleton High School Magazine

The Magazine of Christleton High School Autumn/Winter Term 2014 2 Christleton High School Magazine Introducing the 2014-2015 House Captains Year 7 Year 8 7BA1 Edward Dunford 8Ba1 Eliza Rose Michael Dean Daniel Richards 7BA2 Josh Banks 8By1 Xsara Challinor Claudia Lovering Joseph Bratley 7L1 Emma ODonnell 8By2 Elliot Beech Maisie Lawson Eve Chaloner 7L2 Sarah Efobi 8L1 Leah Ogunyemi Will Lawrence Jay Davies 7BY1 Jennifer Thompson 8Ba2 Dominic Wright Maisie Howarth Ellise Bacchus 7BY2 Milly Rumston 8L2 Ruth Campbell Archie Taylor Sam Parsonage Amber Woodbury 8K1 Isabella Ford 7K1 Erin Williams Kyle Moulton Felix Manning 8K2 Ben Lyon 7K2 Evan Vickers Year 10 10Ba1 Briony Vickers Molly Jones Year 9 Harry Ford Year 11 Joe Baldacchino 9Ba1 Alexandria Martin 11B1 Grace Broughton 10Ba2 Sam Richards Tom Martin Chloe Jones Charlotte Hampton 9Ba2 Eleanor Moulson 11B2 Connor Rowbottom 10By1 Saul Duxbury Paige Pedlow Tyler Jones Mark Goldthorpe Owen Wheeler 11B3 Ryan Hardwick 10By2 James Robinson 9By1 Megan Tuck Will MacDonald Arin Theard 11B4 Matthew Rawson Lucy Joyce Katie Barker 9By2 James Day Sarah Walters Denin Rowland Jasmine Prince 11B5 Holly Astle 9K1 James Richards 10K1 Issy Cornwell 11L1 Charlotte Timms Osian Williams Joe Bramall 11L2 Jack Whitehead 9K2 Isaac Dunford 10K2 Graeme Mochrie 11L3 Finlay Wojitan 9L1 Reece Owens 10L1 Jack Bailey 11L4 Lauren Sharples Myles Carter Sophie Runciman 11L5 Sam Brearey 9L2 Maggie Corr 10L2 Robi-Lea Creswell Emma Ogunyemi Arran Brearey Beth Lyon Winter Term 2014 3 Welcome to Contents 4 Headteacher’s Report -

1St XI ECB Premier League

1st XI ECB Premier League SATURDAY, APRIL 23 Bowdon v Bramhall Hyde v Chester BH Macclesfield v Alderley Edge Neston v Cheadle Toft v Nantwich Urmston v Timperley SATURDAY, APRIL 30 Alderley Edge v Toft Bramhall v Macclesfield Cheadle v Hyde Chester BH v Bowdon Nantwich v Urmston Timperley v Neston SATURDAY. MAY 7 Bowdon v Hyde Macclesfield v Chester BH Neston v Nantwich Timperley v Cheadle Toft v Bramhall Urmston v Alderley Edge SATURDAY, MAY 14 Alderley Edge v Neston Bramhall v Urmston Cheadle v Bowdon Chester BH v Toft Hyde v Macclesfield Nantwich v Timperley SATURDAY MAY 21 Macclesfield v Bowdon Nantwich v Cheadle Neston v Bramhall Timperley v Alderley Edge Toft v Hyde Urmston v Chester BH SATURDAY, MAY 28 Alderley Edge v Nantwich Bowdon v Toft Bramhall v Timperley Cheadle v Macclesfield Chester BH v Neston Hyde v Urmston P3 Fixtures SATURDAY, JUNE 4 Alderley Edge v Cheadle Nantwich v Bramhall Neston v Hyde Tinperley v Chester BH Toft v Macclesfield Urmston v Bowdon SATURDAY. JUNE 11 Bowdon v Neston Bramhall v Alderley Edge Cheadle v Toft Chester BH v Nantwich Macclesfield v Urmston Timperley v Hyde SATURDAY, JUNE 18 Alderley Edge v Chester BH Bramhall v Cheadle Nantwich v Hyde Neston v Macclesfield Timperley v Bowdon Urmston v Toft SATURDAY, JUNE 25 Bowdon v Nantwich Cheadle v Urmston Chester BH v Bramhall Hyde v Alderley Edge Timperley v Macclesfield Toft v Neston SATURDAY, JULY 2 Alderley Edge v Bowdon Bramhall v Hyde Chester BH v Cheadle Nantwich v Macclesfield Neston v Urmston Timperley v Toft SATURDAY. -

Roadside Hedge and Tree Maintenance Programme

Roadside hedge and tree maintenance programme The programme for Cheshire East Higways’ hedge cutting in 2013/14 is shown below. It is due to commence in mid-October and scheduled for approximately 4 weeks. Two teams operating at the same time will cover the 30km and 162 sites Team 1 Team 2 Congleton LAP Knutsford LAP Crewe LAP Wilmslow LAP Nantwich LAP Poynton LAP Macclesfield LAP within the Cheshire East area in the following order:- LAP = Local Area Partnership. A map can be viewed: http://www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/PDF/laps-wards-a3[2].pdf The 2013 Hedge Inventory is as follows: 1 2013 HEDGE INVENTORY CHESHIRE EAST HIGHWAYS LAP 2 Peel Lne/Peel drive rhs of jct. Astbury Congleton 3 Alexandra Rd./Booth Lane Middlewich each side link FW Congleton 4 Astbury St./Banky Fields P.R.W Congleton Congleton 5 Audley Rd./Barley Croft Alsager between 81/83 Congleton 6 Bradwall Rd./Twemlow Avenue Sandbach link FW Congleton 7 Centurian Way Verges Middlewich Congleton 8 Chatsworth Dr. (Springfield Dr.) Congleton Congleton 9 Clayton By-Pass from River Dane to Barn Rd RA Congleton Congleton Clayton By-Pass From Barn Rd RA to traffic lights Rood Hill 10 Congleton Congleton 11 Clayton By-Pass from Barn Rd RA to traffic lights Rood Hill on Congleton Tescos side 12 Cockshuts from Silver St/Canal St towards St Peters Congleton Congleton Cookesmere Lane Sandbach 375199,361652 Swallow Dv to 13 Congleton Dove Cl 14 Coronation Crescent/Mill Hill Lane Sandbach link path Congleton 15 Dale Place on lhs travelling down 386982,362894 Congleton Congleton Dane Close/Cranberry Moss between 20 & 34 link path 16 Congleton Congleton 17 Edinburgh Rd. -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

124 Middlewich Road Sandbach Cheshire CW11 1FH

124 Middlewich Road Sandbach Cheshire CW11 1FH This quirky detached family home sits on a very generous plot and offers a wealth of charm and character. Requiring some updating the property is offered for sale with no upward chain! Accommodation briefly comprises; open porch leads to the lovely spacious square hallway, this gives access to the guest W/C and the lounge / dining room which is of particularly pleasing proportions and can be separated by means of an archway with shaped closing double doors. The sun room is off the living room, good size kitchen over looking the rear garden. Bathroom with separate W/C and two ground floor bedrooms. To the first floor there are two further bedrooms. Integral door from the house leads to the utility room and double garage. One of the garages has an inspection pit. Externally there are front and rear gardens, the rear garden having a pleasing outlook ove the boys School playing fields. Ample parking and turning space to the front. Situated within walking distance to the town centre and both local high Schools. Sandbach is a historical market town located within the South of Cheshire. Quaint shops and half-timbered Tudor pubs decorate the town’s classic Cobbles which also play host to the bustling market on Thursdays. With a strong community spirit, many local amenities and fantastic eateries, Sandbach is the perfect location to buy your next property. It also provides excellent commuting links, with the centre itself sat only one mile from junction 17 of the M6 motorway and only a short drive to Sandbach train station. -

Northwich Transport Strategy Summary 2018

Cheshire West & Chester Council Northwich Transport Strategy Summary 2018 Visit: cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk Contents 3 Foreword 4 Identifying local issues and concerns 6 Our proposed actions and measures 7 The town centre 7 Improving local road capacity 8 Safe and sustainable 9 Improving longer distance connectivity 9 Longer term major schemes 10 Taking work forward Northwich Transport Strategy Summary 3 Foreword Northwich Transport Strategy was approved by the Council’s Cabinet in May 2018. It aims to assist with the delivery of a number of the Council’s wider goals and ambitions to make a real difference to Northwich now and in the years to come. This summary sets out the main priorities and actions to deliver a series of transport improvements in Northwich over the next 15 years. These will be essential to support a number of our wider objectives including: • Capitalising on the £130m of public • Addressing traffic congestion and private sector investment to problems on the local road network transform the town including the including the town centre, the £80m Baron’s Quay development; Hartford corridor and access to • Supporting future housing growth. Gadbrook Park; The Local Plan allocates 4,300 • Taking steps to encourage more new dwellings and 30 hectares people to walk or cycle especially of development land in the town for shorter journeys; up to 2030; • Working to improve local bus and • Supporting the objectives contained in four Neighbourhood Plans; rail networks and encouraging more people to use these services; and • Responding to the e-Petition for a new Barnton / Winnington • Taking full advantage of the Swing bridge, signed by more longer term opportunities than 1,200 people, and preparing and benefits arising a suitable and realistic scheme from the HS2 to improve the problems here; rail project. -

Cheshire Rugby Football Union (1875)

Cheshire Rugby Football Union (1875) HANDBOOK 2015 / 2016 www.cheshirerfu.co.uk Cheshire Rugby Football Union www.cheshirerfu.co.uk ________________________________________ MEMBERSHIP CARD SEASON 2015/2016 Name…………………………………………………………… Club……………………………………………………………… As a member of Cheshire RFU Ltd I/We agree to abide by and to be subject to the Rules and Regulations of Cheshire RFU Ltd and the RFU. Cheshire Membership Subscriptions Annual Subscription £15.00 Life Membership £120.00 Please apply to: Jane Cliff Individual Members Secretary 1 Alcumlow Cottage, Brook Lane, Astbury, Congleton, Cheshire, CW12 4TJ. 01260 270624 E-mail: [email protected] 2 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Notice is hereby given to all Members that the Annual General Meeting of the Cheshire R.F.U. Ltd will be held at Chester R.U.F.C Hare Lane, Vicars Cross, Chester On 9th June 2016 at 6.30pm. Cheshire Rugby Football Union Ltd. Incorporated under the Industrial & Provident Societies Act 1965 No 28989R 3 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Many Presidents have stated that they are extremely honoured to have been elected President of the County. To me it is the greatest honour of my life to be elected your President . As many Past Presidents have made it their mission during their tenure to visit as many of the County’s Clubs as possible, I will endeavour to continue in the same vein. Having been in the fortunate position to have visited many Clubs in an official capacity (referee) it will give me great pleasure to visit on a more informal basis, hoping to assist any Club that can utilise the County’s help and support. -

Index of Cheshire Place-Names

INDEX OF CHESHIRE PLACE-NAMES Acton, 12 Bowdon, 14 Adlington, 7 Bradford, 12 Alcumlow, 9 Bradley, 12 Alderley, 3, 9 Bradwall, 14 Aldersey, 10 Bramhall, 14 Aldford, 1,2, 12, 21 Bredbury, 12 Alpraham, 9 Brereton, 14 Alsager, 10 Bridgemere, 14 Altrincham, 7 Bridge Traffbrd, 16 n Alvanley, 10 Brindley, 14 Alvaston, 10 Brinnington, 7 Anderton, 9 Broadbottom, 14 Antrobus, 21 Bromborough, 14 Appleton, 12 Broomhall, 14 Arden, 12 Bruera, 21 Arley, 12 Bucklow, 12 Arrowe, 3 19 Budworth, 10 Ashton, 12 Buerton, 12 Astbury, 13 Buglawton, II n Astle, 13 Bulkeley, 14 Aston, 13 Bunbury, 10, 21 Audlem, 5 Burton, 12 Austerson, 10 Burwardsley, 10 Butley, 10 By ley, 10 Bache, 11 Backford, 13 Baddiley, 10 Caldecote, 14 Baddington, 7 Caldy, 17 Baguley, 10 Calveley, 14 Balderton, 9 Capenhurst, 14 Barnshaw, 10 Garden, 14 Barnston, 10 Carrington, 7 Barnton, 7 Cattenhall, 10 Barrow, 11 Caughall, 14 Barthomley, 9 Chadkirk, 21 Bartington, 7 Cheadle, 3, 21 Barton, 12 Checkley, 10 Batherton, 9 Chelford, 10 Bebington, 7 Chester, 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 16, 17, Beeston, 13 19,21 Bexton, 10 Cheveley, 10 Bickerton, 14 Chidlow, 10 Bickley, 10 Childer Thornton, 13/; Bidston, 10 Cholmondeley, 9 Birkenhead, 14, 19 Cholmondeston, 10 Blackden, 14 Chorley, 12 Blacon, 14 Chorlton, 12 Blakenhall, 14 Chowley, 10 Bollington, 9 Christleton, 3, 6 Bosden, 10 Church Hulme, 21 Bosley, 10 Church Shocklach, 16 n Bostock, 10 Churton, 12 Bough ton, 12 Claughton, 19 171 172 INDEX OF CHESHIRE PLACE-NAMES Claverton, 14 Godley, 10 Clayhanger, 14 Golborne, 14 Clifton, 12 Gore, 11 Clive, 11 Grafton, -

Click to Enter

CW8 4FT BRAND NEW MULTI-LET TRADE & INDUSTRIAL UNITS ON SITE Q3 2021 121,000 SQ . F T INDUSTRIAL Enquire about your perfect TO LET industrial or trade space today HIGH QUALITY SPECULATIVE DEVELOPMENT UNITS STARTING FROM 1,000 SQ.FT ACROSS 7.5 ACRES WINNINGTON BUSINESS PARK NORTHWICH LOCATION Halewood M6 MANCHESTER WIDNES AIRPORT A562 A49 M56 J9 A561 J20a A556 Quarry Bank M56 LIVERPOOL JOHN Tatton Park LENNON AIRPORT RUNCORN J10 A533 Arley Hall & Gardens M6 J19 A34 A533 RIVER MERSEY A49 Alderley Edge Knutsford Frodsham M56 Ellesmere Port A537 A533 A556 M53 M6 Cheshire Oaks Designer Outlet Weaverham A537 NORTHWICH A49 JODRELL BANK OBSERVATORY A556 A34 Delamere Forest CHESTER ZOO Blakemere Village A533 M53 Delamere A556 M6 Holmes Chapel A54 J18 CHESTER Winsford Tarvin A49 Middlewich OULTON PARK CIRCUIT A54 Congleton A533 A49 WINNINGTON BUSINESS PARK NORTHWICH LOCATION A significant new business park for Northwich amidst an area of substantial urban regeneration and development. • 2 miles from Northwich Town Centre and • Junction 19 of the M6 motorway is just 15 minutes’ • Located 18 miles east of Chester and 12 miles • Easy access to the M56 motorway leading to Northwich train station rural drive away south of Warrington Manchester International Airport WARRINGTON CREWE LIVERPOOL MANCHESTER 12 miles 15 miles 26 miles 28 miles NORTHWICH MANCHESTER LIVERPOOL PORT OF RAIL STATION AIRPORT AIRPORT LIVERPOOL 2 miles 17 miles 19 miles 41 miles Winnington is a historic town located in Northwich, due to the proximity of the two merging rivers along with the last few decades has led to an increase in housing Baron’s Quay Shopping Centre located on the bank of the Cheshire.