Religious Ritual and Sacred Space on Board the Ancient Ship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Millet Use by Non-Romans

Finding Millet in the Roman World Charlene Murphy, PhD University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gower Street, London, UK WC1H 0PY [email protected] Abstract Examining the evidence for millet in the Roman empire, during the period, circa 753BC-610AD, presents a number of challenges: a handful of scant mentions in the ancient surviving agrarian texts, only a few fortuitous preserved archaeological finds and limited archaeobotanical and isotopic evidence. Ancient agrarian texts note millet’s ecological preferences and multiple uses. Recent archaeobotanical and isotopic evidence has shown that millet was being used throughout the Roman period. The compiled data suggests that millet consumption was a more complex issue than the ancient sources alone would lead one to believe. Using the recent archaeobotanical study of Insula VI.I from the city of Pompeii, as a case study, the status and role of millet in the Roman world is examined and placed within its economic, cultural and social background across time and space in the Roman world. Millet, Roman, Pompeii, Diet Charlene Murphy Finding Millet in the Roman World 1 Finding Millet in the Roman World Charlene Murphy, PhD University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gordon Square, London, UK WC1H 0PY [email protected] “If you want to waste your time, scatter millet and pick it up again” ( moram si quaeres, sparge miliu[m] et collige) (Jashemski et al. 2002, 137). A proverb scratched on a column in the peristyle of the House of M. Holconius Rufus (VIII.4.4) at Pompeii Introduction This study seeks to examine the record of ‘millet’, which includes both Setaria italia (L.) P. -

NYARNG-HMWMP.Pdf

ii Table of Contents iii Table of Contents Table of Contents Section Page Chapter 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................1-1 Purpose and Scope ...............................................................................................................................1-1 Reviews and Revisions..........................................................................................................................1-1 Applicable Regulations ..........................................................................................................................1-2 Federal Regulations ..........................................................................................................................1-2 State Regulations ..............................................................................................................................1-2 Military Regulations ...........................................................................................................................1-2 Local Regulations, Ordinances, and Codes......................................................................................1-4 Contractual Obligations .....................................................................................................................1-4 Regulatory Agency Contacts .................................................................................................................1-4 Environmental Office Point of Contacts.................................................................................................1-5 -

What Do We Face?

Commentary by Steve Henningsen January 2017 What Do We Face? 'My father is Janus, the god of two faces. I am used to seeing through masks and deceptions.” ― Rick Riordan, The Blood of Olympus “I prefer to see myself as the Janus, the two-faced god who is half Pollyanna and half Cassandra, warning of the future and perhaps living too much in the past – a combination of both.” –Ray Bradbury, American author Wikipedia defines the ancient Roman god Janus as “the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, doorways, passages, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces, since he looks to the future and to the past. It is conventionally thought that the month of January is named for Janus, but according to ancient Roman farmers' almanacs Juno was the tutelary deity of the month.” Janus can also be thought of as two-faced, as in hypocritical or deceitful. Either in his transitional or two- faced way, Janus has seemed to hover over our heads lately. Many wonder which President Trump will show up after the inauguration; the blustering, narcistic one that will tear up past treaties, impose border taxes and Tweet out whatever comes to mind or a more chilled, Presidential pondering Trump that will seek guidance from his advisors before Tweeting, I mean deciding, on difficult decisions. Has the true face of the news networks come to light as “fake news” stories permeate the media? Is the ongoing battle between inflation and deflation showing signs inflation is finally gaining the upper edge? Is it the U.S. -

Our Steel Drum Program – a Perfect Fit for Great Logistics

From the fi rst idea to end of useful life – MAUSER today. Global: World-wide market presence with more than 60 locations in over 30 countries. High quality: We know all aspects of our business and our products. Quality and security are key. Customer-focused: MAUSER serves international blue chips in the chemical, petrochemical, pharmaceutical and food industries as well as numerous regional accounts. We are experts for international standardization and specialties. Innovative: Numerous patents and awards MAUSER Holding GmbH REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS NCG demonstrate the MAUSER spirit for innovation. Schildgesstraße 71-163 National Container Group LLC SBU Asia 50321 Brühl, Germany West 38th Street 3620 Full-liner: The MAUSER product portfolio MAUSER Singapore Pte Ltd Phone: +49 (0) 2232 78-1000 60632 Chicago, USA 51 Benoi Road Blk 1, includes the complete range of rigid industrial Fax: +49 (0) 2232 78-1202 Phone: +1 (0) 773 847-7575 Liang Huat Industrial Complex packaging – plastics packaging, steel drums, Fax: +1 (0) 773 847-7557 [email protected] 629908 Singapore fi ber drums, composite IBCs; from small bottles www.mausergroup.com Phone: +65 (0) 68969321 [email protected] to 1250 l / 330 gal. IBCs. Fax: +65 (0) 68969327 www.nationalcontainer.com NCG Europe GmbH More than packaging: Process technology and SBU Europe Schildgesstraße 71-163 MAUSER Our steel drum program blow molding equipment are designed and built 50321 Brühl, Germany Kunststoffverpackungen GmbH in-house. Phone: +49 (0) 2232 78-1880 Schildgesstraße 71-163 – a perfect fi t for great Fax: +49 (0) 2232 78-1888 50321 Brühl, Germany MAUSER today is much more than a producer: Phone: +49 (0) 2232 78-1000 [email protected] logistics. -

Magic in Private and Public Lives of the Ancient Romans

COLLECTANEA PHILOLOGICA XXIII, 2020: 53–72 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-0319.23.04 Idaliana KACZOR Uniwersytet Łódzki MAGIC IN PRIVATE AND PUBLIC LIVES OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS The Romans practiced magic in their private and public life. Besides magical practices against the property and lives of people, the Romans also used generally known and used protective and healing magic. Sometimes magical practices were used in official religious ceremonies for the safety of the civil and sacral community of the Romans. Keywords: ancient magic practice, homeopathic magic, black magic, ancient Roman religion, Roman religious festivals MAGIE IM PRIVATEN UND ÖFFENTLICHEN LEBEN DER ALTEN RÖMER Die Römer praktizierten Magie in ihrem privaten und öffentlichen Leben. Neben magische Praktik- en gegen das Eigentum und das Leben von Menschen, verwendeten die Römer auch allgemein bekannte und verwendete Schutz- und Heilmagie. Manchmal wurden magische Praktiken in offiziellen religiösen Zeremonien zur Sicherheit der bürgerlichen und sakralen Gemeinschaft der Römer angewendet. Schlüsselwörter: alte magische Praxis, homöopathische Magie, schwarze Magie, alte römi- sche Religion, Römische religiöse Feste Magic, despite our sustained efforts at defining this term, remains a slippery and obscure concept. It is uncertain how magic has been understood and practised in differ- ent cultural contexts and what the difference is (if any) between magical and religious praxis. Similarly, no satisfactory and all-encompassing definition of ‘magic’ exists. It appears that no singular concept of ‘magic’ has ever existed: instead, this polyvalent notion emerged at the crossroads of local custom, religious praxis, superstition, and politics of the day. Individual scholars of magic, positioning themselves as ostensi- bly objective observers (an etic perspective), mostly defined magic in opposition to religion and overemphasised intercultural parallels over differences1. -

Virgil in English Verse Eclogues and Eneid I. Vi

V I R G I L I N E N G L I S H V E R S E — E CL OGUE S an d E NE ID I . VI . B Y TH E W RIGHT HON . SIR CHA RLES BO EN ’ ONE OF H E R MAJ EST Y S LORDS J U ST ICES OF APPEAL ON CE FELLOW AND N O W VI S I T OR OF BALLI O L C OLLE GE H O D. L O TH E NI VERS I Y O O ORD C . U X N . F T F F HON . D . O THE U N IVERS I Y O E D I NB RGH LL . F T F U SE CON D E DITION LONDON J O HN M Y A L B E M A RL E T E ET U RRA , S R 1 889 a A l l. r i g h t s w w r v ml wi o q fi g ? PRIN TED BY ‘ - SPO ISWOODE AN D CO . N EW S REE S U RE TT , T T Q A LON DON E P R E F A C . A TRANSLATOR of Virgil into E n glish verse finds the road along w hich he has undertaken to travel strewn with the bleachin g bones of unfortunate pilgrims who have pre c ede d him Th a o f e . e adventures an d the f te the great r number have been briefly set forth in an essay published by the late Profes sor Conington in the Quar terly Review of J uly 1 86 1 , and reprinted in the first volume of his m iscellaneous w s . -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

Chthonians in Sicily Curbera, Jaime B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1997; 38, 4; Proquest Pg

Chthonians in Sicily Curbera, Jaime B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1997; 38, 4; ProQuest pg. 397 Chthonians in Sicily Jaime B. Curbera To the memory of Giuseppe Nenci ICILY WAS FAMOUS for her chthonic deities. 1 According to tradition, Hades abducted Kore at Syracuse, Henna, or SAetna; Pindar calls Acragas <l>EpoE<j)6vac; EDOC; (Pyth. 12.2); and the whole island was said to be sacred to Demeter and Kore (Diod. 5.2.3; Cic. Verr. 2.4.106). Indeed, archaeological and numismatic evidence abundantly confirms the literary sources.2 This paper deals with some previously unnoticed epi thets of Sicily's chthonic gods and with the reflection of their cult on personal names on the island. I. The Kyria Earlier in this century, a grave in ancient Centuripae, some 30 km southwest of Mt Aetna, yielded an interesting lead curse tablet, first published by Domenico Comparetti after a drawing by Paolo Orsi, and again, in apparent ignorance of Comparetti's edition, by Francesco Ribezzo with a drawing from autopsy.3 Neither text was satisfactory. Using Orsi's and Ribezzo's drawings, J. J. E. Hondius, "adiuvantibus Cr[onert] et Wil h[elm]," produced in 1929 what is now the best text, SEG IV 61. I Abbreviations: DTAud=A. Audollent, Defixionum tabellae quotquot in notuerunt (Paris 1904); DTWu=R. Wunsch, Defixionum tabellae (Berlin 1897); IGDS=L. Dubois, Inscriptions grecques dialectales de Sicile (Rome 1989); Jordan=D. R. Jordan, • A Survey of Greek Defixiones Not Included in the Special Corpora," GRBS 26 (1985) 151-97. 2 See e.g. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

R12-13,102811 Prt 177

ISS. GOVERNMENT INFORMATION GPO Pt. 177 49 CFR Ch. I (10—1—10 Edition) WARNING—MAY CONTAIN EXPLO engine using liquid fuel that has a flash SIVE MIXTURES WITH AIR—KEEP point less than 38 °C (100 5F), the fuel IGNITION SOURCES AWAY WHEN tank is empty, and the engine is run OPENING until it stalls for lack of fuel; (2) The motor vehicle or mechanical (6) A motor vehicle or mechanical equipment has an internal combustion equipments ignition key may in not be engine using liquid fuel that has a flash the ignition while the vehicle or me point of 38 °C (100 °F) or higher, the fuel chanical equipment is stowed aboard a tank contains 418 L (110 gallons) of fuel vessel. or less, and there are no fuel leaks in (b) All equipment used for handling any portion of the fuel system; vehicles or mechanical equipment (3) The motor vehicle or mechanical must be designed so that the fuel tank equipment is stowed in a hold or com and fuel system of the vehicle or me partment designated by the adminis chanical equipment are protected from tration of the country in which the stress that might cause rupture or vessel is registered other damage incident to handling. to be specially suit (c) Two hand-held, portable, dry ed for vehicles. See 46 CFR 70.10-1 and chemical fire extinguishers of at least 90.10—38 for U.S. vessels; 4.5 kg (10 pounds) capacity each must (4) The motor vehicle or mechanical equipment be separately located in an accessible is electrically powered by location in each hold or compartment wet electric storage batteries; or in which any motor vehicle or mechan (5) The motor vehicle or mechanical ical equipment is stowed. -

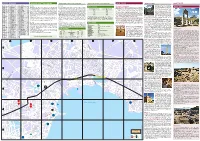

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep.