Under and Beyond (The Skin) Artistic Process, Trauma and Embodiment in Image-Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr

Nov 5 Sat 2 :30 PM WILLIAM WEGMAN Nov 26 Sat 2 :30 PM "SHORT STORY VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr . Wegman appeared on the Tonite Show last summer . Now he works at home in his Dave Olive lives in North Liberty, Iowa, own color studio . He will be premiering where he teaches elementary school . videotapes produced at his color studio and at WGBH Boston . JOE DEA "Short Stories" Nov 12 Sat 2 :30 PM KIT FITZGERALD Nov 13 Sun 8 :00 PM JOHN SANBORN Mr . Dea is a cartoonist who works in video . N r "EXCHANGE IN THREE PARTS" He lives in Hartford, Connecticut . recently completed at TV Laboratory at WNET 8 Channel 13 and currently showing in the tenth Dec 3 Sat 2 :30 PM JUAN DOWNEY 2W Bienale du Paris . Dec 4 Sun 8 :00 PM "MORE THAN TWO" QQ An experience in audio video stereo perception cc ~ Kit ON Z Fitzgerald and John Sanborn have been artist and an account of a video expedition to a OY in residence at ZBS Media and the TV Lab of WNET primitive tribe in South America : The Yanomany . cc cc Y Channel 13 and are currently involved in the o 0.0 Cn >- s International TV Workshop . Their work will be ]sec 10 Sat 2 :30 PM MARILYN GOLDSTEIN 9 W3(L W V O broadcast this season over Public TV . "Voice of the Handicapped" 0 W "Video Beats Westway" a 0 HZ a a OW Nov 19 Sat 2 :30 PM STEINA a W= W Nov 20 Sun 8 :00 PM "Snowed-in Tape and Other Work - 1977" Dec 11 Sun 8 :00 PM LYNDA BENGLIS / STANTON KAYE a 0 "How's Tricks?" Z c 0>NH . -

Meet the Faculty Candidates

MEET THE FACULTY CANDIDATES Candidates are displayed in alphabetically by last name. Prospective employers are invited to attend and while no event pre-registration is required however they must be registered for the BMES 2018 Annual Meeting. A business card will be required to enter the event. COMPLETE DETAILED CANDIDATE INFORMATION AVAILABLE AT www.bmes.org/faculty. Specialty - Biomaterials Alessia Battigelli Woo-Sik Jang Sejin Son John Clegg Patrick Jurney Young Hye Song R. Cornelison Kevin McHugh Ryan Stowers Yonghui Ding Yifeng Peng Varadraj Vernekar Victor Hernandez-Gordillo Shantanu Pradhan Scott Wilson Marian Hettiaratchi Eiji Saito Yaoying Wu Era Jain Andrew Shoffstall Specialty - Biomechanics Adam Abraham Vince Fiore Panagiotis Mistriotis Edward Bonnevie Zeinab Hajjarian Simone Rossi Alexander Caulk Xiao Hu Alireza Yazdani Venkat Keshav Chivukula Heidi Kloefkorn Rana Zakerzadeh Jacopo Ferruzzi Yizeng Li Specialty - Biomedical Imaging Mahdi Bayat Chong Huang Katheryne Wilson Zhichao Fan Jingfei Liu Kihwan Han Alexandra Walsh Specialty - BioMEMS Jaehwan Jung Aniruddh Sarkar Mengxi Wu Specialty - Cardiovascular Engineering Reza Avaz Kristin French Zhenglun (Alan) Wei Specialty - Cellular Engineering Annie Bowles Kate Galloway Kuei-Chun Wang Alexander Buffone Laurel Hind Mahsa Dabagh Matthew Kutys See other side for more candidates Specialty - Device Engineering (Microfluidics, Electronics, Machine-Body interface) Taslim Al-Hilal Brian Johnson David Myers Jungil Choi Tae Jin Kim Max Villa Haishui Huang Jiannan Li Ying Wang Specialty -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

USI2019 Usievents.Com

2019 24 25 usievents.com #USI2019 line-up Robert PLOMIN MRC Research Professor of Behavioural Genetics, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience KING’S COLLEGE LONDON THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE DNA REVOLUTION Prof. Plomin is one of the world’s top behavioral geneticists who offers a unique, insider’s view of the exciting synergies that came from combining genetics and psychology. His research shows that inherited DNA differences are the major systematic force that make us who we are as individuals. The DNA Revolution, namely using DNA to predict our psychological problems and promise from birth, calls for a radical rethink about what makes us who we are, with sweeping—and no doubt controversial—implications for the way we think about parenting, education and the events that shape our lives. A pioneer of what’s sometimes called “hereditarian” science. - The Guardian - Read Blueprint: How DNA makes us who we are Sylvia EARLE Robert Oceanographer PLOMIN © Todd Richard_ synergy productions synergy Richard_ © Todd NO WATER, NO LIFE. NO BLUE, NO GREEN Dr. Sylvia Earle is a living legend. If the celebrated oceanographer, marine biologist, explorer, author, and lecturer isn’t already your hero, allow us to enlighten you. ‘Her Deepness’ has spent nearly a year of her life underwater, logging more than 7,000 hours beneath the surface. She has led countless deep-sea expeditions, was the first female chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the first human—male or female—to complete an untethered walk across the seafloor at a depth of 1,250 feet. Sylvia has been a National Geographic explorer-in-residence since 1998, and continues to share her knowledge and experiences on stage, through film, in writing, and beyond. -

Control of a Powered Ankle-Foot Prosthesis Based on a Neuromuscular Model

TNSRE – 2009-00034 1 Control of a Powered Ankle-Foot Prosthesis Based on a Neuromuscular Model Michael F. Eilenberg, Hartmut Geyer, and Hugh Herr, Member, IEEE devices permit some energy storage during controlled Abstract— Control schemes for powered ankle-foot prostheses dorsiflexion and plantar flexion, and subsequent energy rely upon fixed torque-ankle state relationships obtained from release during powered plantar flexion, much like the Achilles measurements of intact humans walking at target speeds and tendon in the intact human [3], [4]. Although this passive- across known terrains. Although effective at their intended gait elastic behavior is a good approximation to the ankle's speed and terrain, these controllers do not allow for adaptation to environmental disturbances such as speed transients and terrain function during slow walking, normal and fast walking speeds variation. Here we present an adaptive muscle-reflex controller, require the addition of external energy, and thus cannot be based on simulation studies, that utilizes an ankle plantar flexor implemented by any passive ankle-foot device [5]-[7]. This comprising a Hill-type muscle with a positive force feedback deficiency is reflected in the gait of transtibial amputees using reflex. The model's parameters were fitted to match the human passive ankle-foot prostheses. Their self-selected walking ankle’s torque-angle profile as obtained from level-ground speed is slower, and stride length shorter, than normal [8]. In walking measurements of a weight and height-matched intact subject walking at 1 m/sec. Using this single parameter set, addition, their gait is distinctly asymmetric: the range of ankle clinical trials were conducted with a transtibial amputee walking movement on the unaffected side is smaller [9], [10], while, on on level ground, ramp ascent, and ramp descent conditions. -

Mind Over Matter Artforum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_n3_v35/ai_18963443/ Mind over matter ArtForum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist At the Kunsthalle Bern, where Szeemann made his reputation during his eight-year tenure, he organized twelve to fifteen exhibitions a year, turning this venerable institution into a meeting ground for emerging European and American artists. His coup de grace, "When Attitudes Become Form: Live in Your Head," was the first exhibition to bring together post-Minimalist and Conceptual artists in a European institution, and marked a turning point in Szeemann's career - with this show his aesthetic position became increasingly controversial, and due to interference and pressure to adjust his programming from the Kunsthalle's board of directors and Bern's municipal government, he resigned, and set himself up as an Independent curator. If Szeemann succeeded in transforming Bern's Kunsthalle into one of the most dynamic institutions of its time, his 1972 version of Documenta did no less for this art-world staple, held every five years in Kassel, Germany. Conceived as a "100-Day Event," it brought together artists such as Richard Serra, Paul Thek, Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, and Rebecca Horn, and included not only painting and sculpture but installations, performances, Happenings, and, of course, events that lasted the full 100 days, such as Joseph Beuys' Office for Direct Democracy. Artists have always responded to Szeemann and his approach to curating, which he himself describes as a "structured chaos." Of "Monte Verita," a show mapping the visionary utopias of the early twentieth century, Mario Merz said Szeemann "visualized the chaos we, as artists, have in our heads. -

Feminist Perspectives on Curating

Feminist perspectives on curating Book or Report Section Published Version Richter, D. (2016) Feminist perspectives on curating. In: Richter, D., Krasny, E. and Perry, L. (eds.) Curating in Feminist Thought. On-Curating, Zurich, pp. 64-76. ISBN 9781532873386 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/74722/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.on-curating.org/issue-29.html#.Wm8P9a5l-Uk Publisher: On-Curating All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online ONN CURATING.org Issue 29 / May 2016 Notes on Curating, freely distributed, non-commercial Curating in Feminist Thought WWithith CContributionsontributions bbyy NNanneanne BBuurmanuurman LLauraaura CastagniniCastagnini SSusanneusanne ClausenClausen LLinaina DzuverovicDzuverovic VVictoriaictoria HorneHorne AAmeliamelia JJonesones EElkelke KKrasnyrasny KKirstenirsten LLloydloyd MMichaelaichaela MMeliánelián GGabrielleabrielle MMoseroser HHeikeeike MMunderunder LLaraara PPerryerry HHelenaelena RReckitteckitt MMauraaura RReillyeilly IIrenerene RevellRevell JJennyenny RichardsRichards DDorotheeorothee RichterRichter HHilaryilary RRobinsonobinson SStellatella RRolligollig JJulianeuliane SaupeSaupe SSigridigrid SSchadechade CCatherineatherine SSpencerpencer Szuper Gallery, I will survive, film still, single-channel video, 7:55 min. Contents 02 82 Editorial It’s Time for Action! Elke Krasny, Lara Perry, Dorothee Richter Heike Munder 05 91 Feminist Subjects versus Feminist Effects: Public Service Announcement: The Curating of Feminist Art On the Viewer’s Rolein Curatorial Production (or is it the Feminist Curating of Art?) Lara Perry Amelia Jones 96 22 Curatorial Materialism. -

Human Enhancement Technologies and Our Merger with Machines

Human Enhancement and Technologies Our Merger with Machines Human • Woodrow Barfield and Blodgett-Ford Sayoko Enhancement Technologies and Our Merger with Machines Edited by Woodrow Barfield and Sayoko Blodgett-Ford Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Philosophies www.mdpi.com/journal/philosophies Human Enhancement Technologies and Our Merger with Machines Human Enhancement Technologies and Our Merger with Machines Editors Woodrow Barfield Sayoko Blodgett-Ford MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editors Woodrow Barfield Sayoko Blodgett-Ford Visiting Professor, University of Turin Boston College Law School Affiliate, Whitaker Institute, NUI, Galway USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Philosophies (ISSN 2409-9287) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/philosophies/special issues/human enhancement technologies). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-0365-0904-4 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-0365-0905-1 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of N. M. Ford. © 2021 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

Hugh Herr Wants to Build a More Perfect Human

strategy+business ISSUE 85 WINTER 2016 Hugh Herr Wants to Build a More Perfect Human At MIT’s Media Lab, an engineer and biophysicist — and double amputee — is designing prosthetics that connect body and brain. BY SALLY HELGESEN REPRINT 16410 feature innovation 1 AT MIT’S MEDIA LAB, AN ENGINEER AND BIOPHYSICIST — AND HUGHDOUBLE AMPUTEE — IS DESIGNING PROSTHETICS THAT CONNECT BODY AND HERR BRAIN BY SALLY HELGESEN feature WANTS innovation TO BUILD A MORE 2 PERFECT HUMAN Sally Helgesen [email protected] is an author, speaker, and leadership development consultant whose most recent book is The Female Vision: Women’s Real Power at Work (with Julie Johnson; Berrett- Koehler, 2010). Hugh Herr sits at a table in his austere glass office we have to ask ourselves now is: What would be more in the famous Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute useful here, skin or polymer? Fit, function, comfort, and feature of Technology, scrolling through images of a striking aesthetics will dictate our decisions.” fashion model born without a right forearm. As head of A computer scientist, mechanical engineer, and biomechatronics research at MIT and one of the world’s biophysicist, Herr is himself a double amputee. And innovation leading developers of wearable robotics, Herr is making his immersion in robotics was initially driven by a per- a point about how disability is becoming obsolete as the sonal quest to develop superior prosthetics. By analyz- boundary between humans and robots vanishes. ing human motion, studying how electronic devices The model, Rebekah Marine, strikes a pose on the interface with the nervous system, and using live mus- runway. -

IMAGINING WHITENESS in ART a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame In

IMAGINING WHITENESS IN ART A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Art by Joseph Small Martina Lopez, Director Graduate Program in Art, Art History, and Design Notre Dame, Indiana April 2011 © Copyright 2011 Joseph Small CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction......................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Paul McCarthy and the Performance ............................................................... 2 Figure 1: Still from Paul McCarthy’s Class Fool....................................................... 4 Chapter 3: Sally Mann and the Landscape .......................................................................12 Figure 2: Sally Mann’s Untitled (Gettysburg), 2001..............................................14 Chapter 4: Matthew Barney and the Revival of Whiteness .............................................20 Figure 3: Still from Matthew Barney's Cremaster 3, 2002....................................26 Chapter 5: Conclusion ......................................................................................................29 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................31 ii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION The inability to distinguish between skin color and culture, nationality and race, and the personal and the political, often makes finding whiteness in art difficult and furthers society’s -

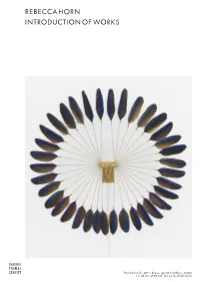

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

The Recurring Desire to Experience by Zakriya Rabani a Non-Thesis

The Recurring Desire To Experience By Zakriya Rabani A non-thesis project in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts School of Art and Art History College of the Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Cesar Cornejo, PHD Committee Member: Wendy Babcox, MFA Committee Member: Gregory Green, MFA Date of Approval: 04/11/2018 Keywords: installation, skateboards, mediated motion, soul, essence, used materials, imagination, potential, experience ⓒ Copyright 2018, Zakriya Rabani This paper reflects my worldview. I am not an expert on theory, people, life, sport, or even art, I can however speak about the concept of experience in my own life. Experience teaches us how to live, how to fail and succeed, but most importantly how to be what it is we desire. From a young age, my desire was to be great at everything, I felt I could achieve anything if I tried hard enough. I believe that this sense of desire is a recurring feeling throughout our lives, no matter the task, sport or occupancy. What is seen, felt and can be interpreted is shaped by experience, this is something I have realized through my upbringing and education. It is our participation with objects, environments and people that allow us to retain information. How we participate is unique to each individual, causing different actions and ideas to occur. Through “ ‘seeing yourself sensing’, a moment of perception, when the viewer pauses to consider what they are experiencing” and mediated motion1 where “viewers become more conscious of the act of movement through space.” I want participants to see what I see in the world.