Mind Over Matter Artforum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr

Nov 5 Sat 2 :30 PM WILLIAM WEGMAN Nov 26 Sat 2 :30 PM "SHORT STORY VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr . Wegman appeared on the Tonite Show last summer . Now he works at home in his Dave Olive lives in North Liberty, Iowa, own color studio . He will be premiering where he teaches elementary school . videotapes produced at his color studio and at WGBH Boston . JOE DEA "Short Stories" Nov 12 Sat 2 :30 PM KIT FITZGERALD Nov 13 Sun 8 :00 PM JOHN SANBORN Mr . Dea is a cartoonist who works in video . N r "EXCHANGE IN THREE PARTS" He lives in Hartford, Connecticut . recently completed at TV Laboratory at WNET 8 Channel 13 and currently showing in the tenth Dec 3 Sat 2 :30 PM JUAN DOWNEY 2W Bienale du Paris . Dec 4 Sun 8 :00 PM "MORE THAN TWO" QQ An experience in audio video stereo perception cc ~ Kit ON Z Fitzgerald and John Sanborn have been artist and an account of a video expedition to a OY in residence at ZBS Media and the TV Lab of WNET primitive tribe in South America : The Yanomany . cc cc Y Channel 13 and are currently involved in the o 0.0 Cn >- s International TV Workshop . Their work will be ]sec 10 Sat 2 :30 PM MARILYN GOLDSTEIN 9 W3(L W V O broadcast this season over Public TV . "Voice of the Handicapped" 0 W "Video Beats Westway" a 0 HZ a a OW Nov 19 Sat 2 :30 PM STEINA a W= W Nov 20 Sun 8 :00 PM "Snowed-in Tape and Other Work - 1977" Dec 11 Sun 8 :00 PM LYNDA BENGLIS / STANTON KAYE a 0 "How's Tricks?" Z c 0>NH . -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

DIE KÜNSTLER DES Di DANIEL SPOERRI

FONDAZIONE »HIC TERMINUS HAERET« Il Giardino di Daniel Spoerri ONLUS Loc. Il Giardino I - 58038 Seggiano GR L I E fon 0039 0564 950 026 W www.danielspoerri.org T T [email protected] O R T S DIE KÜNSTLER DES N U K M U R O F m i GIARDINO « i r r e o p S l di DANIEL SPOERRI e i n a D GLI ARTISTI DEL GIARDINO DI DANIEL SPOERRI i d o n i d r a i G s e d r e l t s n ̈ u K e i D » g n u l l e t s s u A r e d h c i l s s ä l n a t n i e h c s r e t f e H s e s e i D LOC. IL GIARDINO | I - 58038 SEGGIANO (GR) www.danielspoerri.org Impressum FORUM KUNST ROTTWEIL Dieses Heft erscheint anlässlich de r Ausstellung Friedrichsplatz Die Künsetrl des Giardino di Daniel Spoerri D - 78628 Rottweil im FORUM KUNST ROTTWEIL fon 0049 (0)741 494 320 Herausgeber fax 0049 (0)741 942 22 92 Jürgen Knubben www.forumkunstrottweil.de Forum Kunst Rottweil [email protected] Kuratoren Jürgen Knubben ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN / ORARIO Barbara Räderscheidt Dienstag, Mittwoch, Freitag / martedi, mercoledi, venerdi Daniel Spoerri 14:00 – 17:00 Susanne Neumann Donnerstag / giovedi Texte 17:00 – 20:00 Leda Cempellin Samstag und Sonntag / sabato e domenica Jürgen Knubben 10:00 – 13:00 Anna Mazzanti (A.M.) 14:00 – 17:00 Barbara Räderscheidt (B.R.) Daniel Spoerri IL GIARDINO DI DANIEL SPOERRI Übersetzungen »HIC TERMINUS HAERET« NTL, Florenz Il Giardino di Daniel Spoerri ONLUS Katalog & Fotos Loc. -

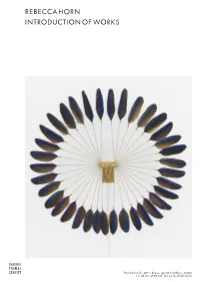

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Douglas Davis and Allison Simmons

This book was edited by Douglas Davis and Allison Simmons • I ... , ...... I ··-. r-·--····: .. :·:.. .. The MIT Press · Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England Copyright© 1977 by Electronic Arts Intermix, Inc. Photographs by Peter Moore © 197 4 by Peter Moore Photographs by Richard Landry© 1973 by Richard Landry • All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in ' writing from the publisher. This book was set in I BM Composer by Tech Data Associates, Inc. and I BM Selectric by Barbara Altman. It was printed and bound by the Murray Printing Company in the United States of America. Library of Congress catalog card number: 76-29198 ISBN: 0-262-04050~ I Elmer•Holmes BobstLibrary NewYork Universi haveand the been United furthermore States v·djoined .b Yother artists. .m both Europe Preface . I eo is no longer th . pioneers; it is becoming as co .• province of a few Open Circuits conference wa smtmhon us anas event pencil or·th paint. · · The. Thish book is based on a conferen : olars, and television producer~• :~~nded by artists, critics, or the future as well as th e past. WI 1mpllcat1ons f rt m New York City in Jan a e Museum of Modern bears the stamp of that time u:yl 1974. Although this volume For th eir· invaluable· . we would. like t o exprassistance with th·1s pro 1· s1onsabout the nature both ~f ta to_p_resents ideas and conclu- an mstitutio T ess our gratitud -

Gerhard Richter

GERHARD RICHTER Born in 1932, Dresden Lives and works in Cologne EDUCATION 1951-56 Studied painting at the Fine Arts Academy in Dresden 1961 Continued his studies at the Fine Arts Academy in Düsseldorf 2001 Doctoris honoris causa of the Université Catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 About Painting S.M.A.K Museum of Contemporary Art, Ghent 2016 Selected Editions, Setareh Gallery, Düsseldorf 2014 Pictures/Series. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen 2013 Tepestries, Gagosian, London 2012 Unique Editions and Graphics, Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach Atlas, Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden Das Prinzip des Seriellen, Galerie Springer & Winckler, Berlin Panorama, Neue und Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin Editions 1965–2011, me Collectors Room, Berlin Survey, Museo de la Ciudad, Quito Survey, Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango del Banco de la República, Bogotá Seven Works, Portland Art Museum, Portland Beirut, Beirut Art Center, Beirut Painting 2012, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, NY Ausstellungsraum Volker Bradtke, Düsseldorf Drawings and Watercolours 1957–2008, Musée du Louvre, Paris 2011 Images of an Era, Bucerius Kunst Forum, Hamburg Sinbad, The FLAG Art Foundation, New York, NY Survey, Caixa Cultural Salvador, Salvador Survey, Caixa Cultural Brasilia, Brasilia Survey, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo Survey, Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul Ado Malagoli, Porto Alegre Glass and Pattern 2010–2011, Galerie Fred Jahn, Munich Editions and Overpainted Photographs, -

Name Distel, Herbert Lebensdaten * 7.8.1942 Bern Bürgerort Hochwald (SO) Staatszugehörigkeit CH

Schweiz richtet Distel sein Atelier in Bern ein und wird zu einem der führenden Vertreter der Berner Kunstszene. Mit der freien Künstlergruppierung Bern 66 prägt er Ausstellungen in der Berner Kunsthalle und nimmt an zahlreichen Ausstellungen im Ausland teil. Seine Wellblech- und Kartonreliefs der mittleren 1960er-Jahre zeigen eine intensive Auseinandersetzung mit Licht und Schatten. Mit grossformatigen Polyesterplastiken beginnen Projekte, die den Werkbegriff und seine institutionelle Definition kommentieren. 1968 Premio nazionale di Scultura all’aperto in Vira Gambarogno; Public Eye, Kunsthalle Hamburg; 1969 Distel, Herbert, Projekt "Canaris" (Ei), 1970, Polyester-Ei Preis für Skulptur der X Bienal de São Paulo. In vielen mit installierter Kamera und Chronometer, Länge 300 cm, Medien – in Aktionen, audiophonischen und audiovisuellen grösster Durchmesser 200 cm, Arbeiten – thematisiert Distel neue Präsentations- und Vermittlungsformen künstlerischer Arbeit. Eines seiner bekanntesten Projekte realisiert er 1970–77 mit dem Schubladenmuseum. Distel wendet sich in dieser Zeit neuen Bearbeitungstiefe Medien zu: Theaterinszenierung, Press-Art, inszenierte Fotografie, Ton- und Filmarbeiten. Das Interesse am Film führt 1985–87 zu Studien bei den polnischen Regisseuren Name Krzysztof Kieslowski und Edward Zebrowski. Distel, Herbert Internationalen Erfolg und Video-Kunstpreise erzielt Distel 1993 mit dem 18-minütigen Video Die Angst Die Macht Die Lebensdaten Bilder des Zauberlehrlings. * 7.8.1942 Bern Herbert Distel lebte mit seiner Frau von 1994–2005 in der Bürgerort Toskana und seither in Niederösterreich. Hochwald (SO) Distels Frühwerk ist der Auseinandersetzung mit der Staatszugehörigkeit Skulptur gewidmet. Sind diese meist aus Polyester CH gefertigten, direkt auf den Boden platzierten Arbeiten anfangs noch weiss, kommt ab 1965 auch Farbe zum Einsatz Vitazeile (Kugelschnitt, 1967). -

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller Art Books, Artists’ Books, Book Arts and Bookworks New York City 2021 JONATHAN A. HILL BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 home page: www.jonathanahill.com JONATHAN A. HILL mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] MEGUMI K. HILL mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] YOSHI HILL mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] Further illustrations can be seen on our webpage. Member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America We accept Master Card, Visa, and American Express. Terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. COVER ILLUSTRATION: © 2020 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York PRINTED IN CHINA 1. ART METROPOLE, bookseller. [From upper cover]: Catalogue No. 5 – Fall 1977: Featuring european Books by Artists. Black & white illus. (some full-page). 47 pp. Large 4to (277 x 205 mm.), pictorial wrap- pers, staple-bound. [Toronto: 1977]. $350.00 A rare and early catalogue issued by Art Metropole, the first large-scale distributors of artists’ books and publications in North America. This catalogue offers dozens of works by European artists such as Abramovic, Beuys, Boltanski, Broodthaers, Buren, Darboven, Dibbets, Ehrenberg, Fil- liou, Fulton, Graham, Rebecca Horn, Hansjörg Mayer, Merz, Nannucci, Polke, Maria Reiche, Rot, Schwitters, Spoerri, Lea Vergine, Vostell, etc. -

Documenta 5 Working Checklist

HARALD SZEEMANN: DOCUMENTA 5 Traveling Exhibition Checklist Please note: This is a working checklist. Dates, titles, media, and dimensions may change. Artwork ICI No. 1 Art & Language Alternate Map for Documenta (Based on Citation A) / Documenta Memorandum (Indexing), 1972 Two-sided poster produced by Art & Language in conjunction with Documenta 5; offset-printed; black-and- white 28.5 x 20 in. (72.5 x 60 cm) Poster credited to Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Ian Burn, Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Harold Hurrrell, Joseph Kosuth, and Mel Ramsden. ICI No. 2 Joseph Beuys aus / from Saltoarte (aka: How the Dictatorship of the Parties Can Overcome), 1975 1 bag and 3 printed elements; The bag was first issued in used by Beuys in several actions and distributed by Beuys at Documenta 5. The bag was reprinted in Spanish by CAYC, Buenos Aires, in a smaller format and distrbuted illegally. Orginally published by Galerie art intermedai, Köln, in 1971, this copy is from the French edition published by POUR. Contains one double sheet with photos from the action "Coyote," "one sheet with photos from the action "Titus / Iphigenia," and one sheet reprinting "Piece 17." 16 ! x 11 " in. (41.5 x 29 cm) ICI No. 3 Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Poster 33 x 23 " in. (84.3 x 60 cm) ICI /Documenta 5 Checklist page 1 of 13 ICI No. 4 Lawrence Weiner A Primer, 1972 Artists' book, letterpress, black-and-white 5 # x 4 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm) Documenta Catalogue & Guide ICI No. 5 Harald Szeemann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, Alexander Kluge, Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Exhibition catalogue, offset-printed, black-and-white & color, featuring a screenprinted cover designed by Edward Ruscha. -

Howardena Pindell

HOWARDENA PINDELL Born in 1943 in Philadelphia, USA Lives and works in New York, USA Education 1965-67 Yale University, New Haven, USA 1961-65 Boston University, Boston, USA Solo Exhibitions 2019 What Remains To Be Seen, Rose Art Museum Waltham, Massachusetts, USA 2018 Howardena Pindell, Document Gallery, Chicago, USA Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts (2018-2019), USA 2017 Howardena Pindell: Recent Paintings, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Howardena Pindell, Honor Fraser, Los Angeles, USA Howardena Pindell, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, Atlanta, USA 2014 Howardena Pindell: Paintings, 1974-1980, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, USA 2013 Howardena Pindell: Video Drawings, 1973-2007, Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston, USA 2009 Howardena Pindell: Autobiography: Strips, Dots, and Video, 1974-2009, Sandler Hudson Gallery, Atlanta, USA 2007 Howardena Pindell: Hidden Histories, Louisiana Art and Science Museum, Baton Rouge, USA 2006 Howardena Pindell: In My Lifetime, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, New York, USA 2004 Howardena Pindell: Works on Paper, 1968-2004, Sragow Gallery, New York, USA Howardena Pindell: Visual Affinities, Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, USA 2003 Howardena Pindell, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, Detroit, USA 2002 Howardena Pindell, Diggs Gallery, Winston-Salem State University, North Carolina, USA 2001 Howardena Pindell: An Intimate Retrospective, Harriet Tubman Museum, Macon, Georgia, USA 2000 Howardena Pindell: Collages, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan, USA Howardena Pindell: Recent Work, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, Chicago, USA 1999 Witness to Our Time: A Decade of Work by Howardena Pindell, The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, USA 1996 Howardena Pindell: Mixed Media on Canvas, Johnson Gallery, Bethel University, St. -

The Museum of Drawers 1970-1977 Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +44 (0) 1394 389950 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/uk The Museum of Drawers 1970- 1977 Five Hundred Works of Modern Art Herbert Distel Edited by Thomas Kramer ISBN 9783858813336 Publisher Scheidegger & Spiess Binding Hardback Territory World excluding Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Puerto Rico, United States, Canada, and Japan Size 300 mm x 200 mm Pages 184 Pages Illustrations 533 color, 17 b&w Price £45.00 Includes original art works by 508 artists, including Beuys, Duchamp, Picasso and Warhol Only book on this icon of 20th-century art in the market The book presents all 500 works in true size The Museum of Drawers is on tour around Europe 2011-13, beginning at Arnolfini Art Center in Bristol (2011) and ending at Whitechapel Gallery in London (2013) The Museum of Drawers is the world's smallest museum of twentieth-century art. This unique piece has been conceived and put together by the Swiss-born artist Herbert Distel in 1970-77. It consists of an old cabinet made to hold reels of sewing silk whose twenty drawers each contain twenty-five compartments. Each of the 500 compartments houses an original miniature work of art, many of which were made especially for the Museum of Drawers. The list of artists represented includes such influential pioneers as Joseph Beuys, Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch, Meret Oppenheim, Pablo Picasso, and Andy Warhol. Following a first presentation as a work-in-progress at the documenta 5 in Kassel (Germany) in 1972, the Museum of Drawers caused sensation internationally. It has been shown several times in New York, including a presentation at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1999, and at many museums around the world. -

New Title Information Time Pieces

New title information Time Pieces Product Details Video Art since 1963 £19 Artist(s) Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Joseph Beuys, Dara Birnbaum, Cerith Founded in 1971 as an artists’ and cultural producers’ initiative, the Wyn Evans, Valie Export, Harun Farocki, Dan Graham, Gary Hill, Video-Forum, with over 1400 international works, is the oldest Laura Horelli, Rebecca Horn, collection of video art in Germany. Christian Jankowski, Joan Jonas, Imi Knoebel, Daniel Knorr, Oleg Kulik, Focal points of the collection are Fluxus, feminist video, historical and Bjorn Melhus, Bruce Nauman, Marcel contemporary video art from Berlin as well as media-reflective Odenbach, Claes Oldenburg, Tony Oursler, Nam June Paik, Bill Viola, approaches. Key works from the early period of video art are equally Wolf Vostell, Robert Wilson, Ming well represented as current productions. Wong, Haegue Yang, Heimo Zobernig Author(s) Sylvia Arnaout, Marius Babias, This book documents the complete contents of the collection and Kathrin Becker, Dieter Daniels, Gisela includes illustrations, forming a comprehensive compendium of Jo Eckhardt, Sophie Goltz, Tabea international video art for artists, curators and teachers. Metzel, Bert Rebhandl Editor(s) Marius Babias, Kathrin Becker, English and German text. Sophie Goltz Publisher Walther Koenig ISBN 9783863350741 Format softback Pages 456 Illustrations illustrated in b&w Dimensions 230mm x 160mm Weight 930 Publication Date: Dec 2013 Distributed by Enquiries Website Cornerhouse Publications +44 (0)161 212 3466 / 3468 www.cornerhousepublications.org HOME [email protected] 2 Tony Wilson Place Twitter Manchester Orders @CornerhousePubs M15 4FN +44 (0) 1752 202301 England [email protected].