IMAGINING WHITENESS in ART a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watch Live As the Cast of Jackass 3 Celebrates the Film's Blu-Ray and DVD 'Launch' with an Evening of Asinine Antics

Watch Live as the Cast of Jackass 3 Celebrates the Film's Blu-ray and DVD 'Launch' With an Evening of Asinine Antics Join the Party Live Tonight, Monday, March 7 on Facebook or Livestream Starting at 8:30 p.m. PT HOLLYWOOD, Calif., March 7, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Jackass fans around the world are invited to share in the outrageous insanity of the official JACKASS 3Blu-ray and DVD launch party by watching all the madness and mayhem LIVE online on the Jackass Facebook page www.facebook.com/jackass or on www.livestream.com/jackass3 tonight, Monday, March 7, beginning at 8:30 p.m. PT. Johnny Knoxville, Bam Margera, Steve-O, Ryan Dunn, Preston Lacy, Jason "Wee Man" Acuna, Chris Pontius, Ehren McGhehey, David England, director Jeff Tremaine and celebrity fans of all things Jackass will be on hand for the exclusive event, taking place on the Paramount Pictures studio lot in Hollywood, California. Fans can watch the red carpet arrivals, as well as the ludicrous--and potentially hazardous--party activities, all for free via the live stream. JACKASS 3 hits home on March 8, 2011 in a jam-packed unrated Blu-ray/DVD Combo with Digital Copy and a Limited Edition two-disc DVD. The entire Jackass crew returns for more side-splitting lunacy and cringe-inducing stunts. From wild animal face- offs to pitiless practical jokes and logic-defying acts of guaranteed pain and suffering, JACKASS 3 reaches new heights in the pursuit of the inventively insane. The JACKASS 3 Blu-ray/DVD Combo with Digital Copy, Limited Edition two-disc DVD and single-disc DVD all include an over- the-top UNRATED version of the film with outrageous footage not seen in theaters, as well as the original theatrical version. -

INSOMNIA Al Pacino. Robin Williams. Hilary Swank. Maura Tierney

INSOMNIA Al Pacino. Robin Williams. Hilary Swank. Maura Tierney. Martin Donovan. Nicky Katt. Paul Dooley. Jonathan Jackson. Larry Holden. Katherine Isabelle. Oliver "Ole" Zemen. Jay Brazeau. Lorne Cardinal. James Hutson. Andrew Campbell. Paula Shaw. Crystal Lowe. Tasha Simms. Malcolm Boddington. Kerry Sandomirsky. Chris Guthior. Ian Tracey. Kate Robbins. Emily Jane Perkins. Dean Wray. INVINCIBLE Tim Roth. Jouko Ahola. Anna Gourari. Jacob Wein. Max Raabe. Gustav Peter Wöhler. Udo Kier. Herbert Golder. Gary Bart. Renate Krössner. Ben-Tzion Hershberg. Rebecca Wein. Raphael Wein. Daniel Wein. Chana Wein. Guntis Pilsums. Torsten Hammann. Jurgis Krasons. Klaus Stiglmeier. James Reeves. Ulrich Bergfelder. Jakov Rafalson. Leva Aleksandrova. Natalie Holtom. Karin Kern. Amanda Lawford. Francesca Marino. Beatrix Reiterer. Adrianne Richards. Sabine Schreitmiller. Kristy Wone. Rudolph Herzog. Les Bubb. Tina Bordhin. Sylvia Vas. Hans-Jürgen Schmiebusch. Joachim Paul Assböck. Alexander Duda. Klaus Haindl. Hark Bohm. Anthony Bramall. André Hennicke. Ilga Martinsone. Valerijs Iskevic. Juris Strenga. Grigorij Kravec. James Mitchell. Milena Gulbe. ITALIAN FOR BEGINNERS Anders W. Berthelson. Anette Støvelbaek. Peter Gantzler. Ann Eleonora Jørgensen. Lars Kaalund. Karen-Lise Mynster. Rikke Wölck. Elsebeth Steentoft. Sara Indrio Jensen. Bent Mejding. Claus Gerving. Jesper Christensen. Carlo Barsotti. Lene Tiemroth. Alex Nyborg Madsen. Steen Svare Hansen. Susanne Oldenburg. Martin Brygmann. IVANSXTC. Danny Huston. Peter Weller. Lisa Enos. Joanne Duckman. Angela Featherstone. Caroleen Feeney. Valeria Golino. Adam Krentzman. Heidi Jo Markel. James Merendino. Tiffani-Amber Thiessen. Morgan Vukovic. Crystal Atkins. Alex Butler. Robert Graham. Marilyn Heston. Courtney Kling. Hal Lieberman. Carol Rose. Victoria Silvstedt. Alison Taylor. Vladimir Tuchinsky. Camille Alick. Bobby Bell. Pria Chattergee. Dino DeConcini. Steve Dickman. Sofia Eng. Sarah Goldberg. -

White Ball-Breaking As Surplus Masculinity in Jackass

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU English Faculty Publications English 2015 The Leisured Testes: White Ball-breaking as Surplus Masculinity in Jackass Christina M. Tourino College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Tourino, Christina M., "The Leisured Testes: White Ball-breaking as Surplus Masculinity in Jackass" (2015). English Faculty Publications. 21. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs/21 © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc The Leisured Testes: White Ball-breaking as Surplus Masculinity in Jackass In Jackass: Number Two (2006), Bam Margera allows Ryan Dunn to brand his posterior with a hot iron depicting male genitalia. Bam cannot tolerate the pain enough to remain perfectly still, so the brand touches him several times, resulting in multiple images that seem blurry or in motion. Bam’s mother, who usually plays the role of game audience for his antics, balks when she learns that her son has been hurt as well as permanently marked. She asks Dunn why anyone would ever burn a friend. “Cause it was funny,” Dunn answers.1 Jackass mines the body in pain as well as the absurd and the taboo, often dealing with one or more of the body’s abject excretions. Jackass offers no compelling narrative arc or cliffhangers, presenting instead a series of discrete segments that explore variations on the singular eponymous focus of the show: playing the fool. This deliberate idiocy is the show’s greatest strength, and its excesses seem calculated to repeatedly provide the viewer with a mix of schadenfreude, horror, and disbelief. -

Feminist Perspectives on Curating

Feminist perspectives on curating Book or Report Section Published Version Richter, D. (2016) Feminist perspectives on curating. In: Richter, D., Krasny, E. and Perry, L. (eds.) Curating in Feminist Thought. On-Curating, Zurich, pp. 64-76. ISBN 9781532873386 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/74722/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.on-curating.org/issue-29.html#.Wm8P9a5l-Uk Publisher: On-Curating All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online ONN CURATING.org Issue 29 / May 2016 Notes on Curating, freely distributed, non-commercial Curating in Feminist Thought WWithith CContributionsontributions bbyy NNanneanne BBuurmanuurman LLauraaura CastagniniCastagnini SSusanneusanne ClausenClausen LLinaina DzuverovicDzuverovic VVictoriaictoria HorneHorne AAmeliamelia JJonesones EElkelke KKrasnyrasny KKirstenirsten LLloydloyd MMichaelaichaela MMeliánelián GGabrielleabrielle MMoseroser HHeikeeike MMunderunder LLaraara PPerryerry HHelenaelena RReckitteckitt MMauraaura RReillyeilly IIrenerene RevellRevell JJennyenny RichardsRichards DDorotheeorothee RichterRichter HHilaryilary RRobinsonobinson SStellatella RRolligollig JJulianeuliane SaupeSaupe SSigridigrid SSchadechade CCatherineatherine SSpencerpencer Szuper Gallery, I will survive, film still, single-channel video, 7:55 min. Contents 02 82 Editorial It’s Time for Action! Elke Krasny, Lara Perry, Dorothee Richter Heike Munder 05 91 Feminist Subjects versus Feminist Effects: Public Service Announcement: The Curating of Feminist Art On the Viewer’s Rolein Curatorial Production (or is it the Feminist Curating of Art?) Lara Perry Amelia Jones 96 22 Curatorial Materialism. -

The Recurring Desire to Experience by Zakriya Rabani a Non-Thesis

The Recurring Desire To Experience By Zakriya Rabani A non-thesis project in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts School of Art and Art History College of the Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Cesar Cornejo, PHD Committee Member: Wendy Babcox, MFA Committee Member: Gregory Green, MFA Date of Approval: 04/11/2018 Keywords: installation, skateboards, mediated motion, soul, essence, used materials, imagination, potential, experience ⓒ Copyright 2018, Zakriya Rabani This paper reflects my worldview. I am not an expert on theory, people, life, sport, or even art, I can however speak about the concept of experience in my own life. Experience teaches us how to live, how to fail and succeed, but most importantly how to be what it is we desire. From a young age, my desire was to be great at everything, I felt I could achieve anything if I tried hard enough. I believe that this sense of desire is a recurring feeling throughout our lives, no matter the task, sport or occupancy. What is seen, felt and can be interpreted is shaped by experience, this is something I have realized through my upbringing and education. It is our participation with objects, environments and people that allow us to retain information. How we participate is unique to each individual, causing different actions and ideas to occur. Through “ ‘seeing yourself sensing’, a moment of perception, when the viewer pauses to consider what they are experiencing” and mediated motion1 where “viewers become more conscious of the act of movement through space.” I want participants to see what I see in the world. -

Stuart Sherman

Heartney, Eleanor. Stuart Sherman. Art In America. December 2009. Stuart Sherman NEW YORK, at 80WSE and Participant by Eleanor Heartney A cross between a magician, a mime, a comic performer in the mode of Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, a theatrical impresario and a high priest, Stuart Sherman was a well-known figure in the downtown avant-garde scene from the late ’70s through the early ’90s, when his career was cut short by AIDS. (He died in 2001.) Because his work has been preserved primarily as videos of perfor- mances and in stacks of casual drawings, photocopies and other scraps of paper, his legacy has gone underground. Last fall, a pair of shows brought him back to life. At New York University’s 80WSE, curators Yolanda Hawkins, John Matturri and John Hagan, who were friends of the artist (and oc- casional participants in his later performances), presented “Begin- ningless Thought/Endless Seeing: The Works of Stuart Sherman,” a visually unprepossessing exhibition that documented the artist’s work in myriad genres. At Participant, “Stuart Sherman: Nothing Up My Sleeve,” curated by Jonathan Berger, focused on Sherman’s artistic genealogy and legacy. Left: Stuart Sherman: Eleventh Spectacle (The Erotic), ca. 1979, performance, Battery Park; at 80WSE. Photo John Mat- What is most striking today about Sherman is the modesty of his turri. ambitions—the two shows suggest a life devoted to little gestures Right: Photograph of Eighth Spectacle, 1977; at Participant. Photo Babette Mangolte. located somewhere on the continuum between comedy and absur- dity. Take, for instance, his 19 “spectacles,” the performance works for which he remains best known, thanks in part to abundant documentation. -

Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment

Jesper JUST Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment November 2019 1/1 “Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment” Alina Cohen November 27, 2019 Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment Alina Cohen Nov 27, 2019 3:37pm Jesper Just, Interpassitivies, at the Royal Danish Theater, 2017. Courtesy of Perrotin. At the 2019 edition of the Venice Biennale, video reigned. Arthur Jafa, who began his career as a cinematographer for commercial directors including Spike Lee and Stanley Kubrick, won the prestigious Golden Lion award for his film The White Album (2018). Meanwhile, one of his frequent collaborators, Kahlil Joseph, who seamlessly crosses between the worlds of music videos and art museums, presented BLKNWS (2019– present), an experimental news media channel aimed at black audiences. Artists including Alex Da Corte, Ian Cheng, Kaari Upson, Ed Atkins, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Stan Douglas , and Hito Steyerl all integrated the medium into dynamic installations. “Video art”—which now encompasses traditional film and digital video as well as a wide range of new media and technology, including virtual reality, video games, and phone apps—represents some of today’s most exciting contemporary work. For further evidence of the medium’s art-world domination, one might examine the artists who were shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2018 and 2019. All eight—Lawrence Abu “Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment” Alina Cohen November 27, 2019 Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo, Tai Shani, Charlotte Prodger, Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, and Luke Willis Thompson—work in video. This video art renaissance derives from an ever-growing range of exhibition methods, improvements in technology, wider institutional acceptance, and artists’ growing ambitions. -

Curating in Feminist Thought

ONN CURATING.org Issue 29 / May 2016 Notes on Curating, freely distributed, non-commercial Curating in Feminist Thought WWithith CContributionsontributions bbyy NNanneanne BBuurmanuurman LLauraaura CastagniniCastagnini SSusanneusanne ClausenClausen LLinaina DzuverovicDzuverovic VVictoriaictoria HorneHorne AAmeliamelia JJonesones EElkelke KKrasnyrasny KKirstenirsten LLloydloyd MMichaelaichaela MMeliánelián GGabrielleabrielle MMoseroser HHeikeeike MMunderunder LLaraara PPerryerry HHelenaelena RReckitteckitt MMauraaura RReillyeilly IIrenerene RevellRevell JJennyenny RichardsRichards DDorotheeorothee RichterRichter HHilaryilary RRobinsonobinson SStellatella RRolligollig JJulianeuliane SaupeSaupe SSigridigrid SSchadechade CCatherineatherine SSpencerpencer Szuper Gallery, I will survive, film still, single-channel video, 7:55 min. Contents 02 82 Editorial It’s Time for Action! Elke Krasny, Lara Perry, Dorothee Richter Heike Munder 05 91 Feminist Subjects versus Feminist Effects: Public Service Announcement: The Curating of Feminist Art On the Viewer’s Rolein Curatorial Production (or is it the Feminist Curating of Art?) Lara Perry Amelia Jones 96 22 Curatorial Materialism. A Feminist Perspective The Six Enemies of Greatness on Independent and Co-Dependent Curating Video programme compiled Elke Krasny by Susanne Clausen and Dorothee Richter 108 27 Performing Feminism ‘Badly’: Slapping Scenes Hotham Street Ladies and Brown Council Susanne Clausen Laura Castagnini 29 116 Feminism Meets the Big Exhibition: Taking Care: Feminist Curatorial Pasts, -

ISSUES in CONTEMPORARY ART (THE THING) Fall 2021 Chri

San José State University Department of Art & Art History ARTH 191A: ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY ART (THE THING) Fall 2021 Christian Boltanski, Personnes, 2010. Paris, Grand Palais. Instructor: Dr. Dore Bowen, Professor of Art History and Visual Culture Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 10-noon (online) Class Days/Time: T/TH 12:30 – 1:45 (online) Prerequisites: Prior upper-division art history coursework Land Acknowledgement We respectfully recognize that San Jose State University exists on the occupied, traditional lands of the Tamyen-Ohlone (Muwekma) People, who have stewarded this land for generations. Course Description This upper-division undergraduate course is devoted to exploring contemporary art practices with a particular focus on artists who engage directly with process, materials, and objects. Over the course of the semester students will become familiar with a variety of artists and media while reading texts that explain, describe, and theorize various approaches to the work discussed. By the end of the semester students will be familiar with a range of artists and writers who grapple with the mystery of things. The first half of the course will address different types of object-based art, while the second half will focus on strategies artists have developed for altering our relationship to objects, such as alternative viewing strategies, museum intervention, and relational aesthetics. Throughout the semester the course will emphasize the way the contemporary practices discussed are inspired by, or a reaction to, earlier artists and movements. Course Structure See Canvas for full details on assigned readings and videos, as well as assignments. This schedule below is slightly abbreviated so that you can download to your computer for reference. -

Chance, Perfection, Simple Or Complex?

CHANCE, PERFECTION, SIMPLE OR COMPLEX? CURATED BY TONY GODFREY Pablo Capati III Nona Garcia Kawayan de Guia Nilo Ilarde Geraldine Javier Donna Ong Christina Quisumbing Ramilo Zhao Renhui DECEMBER 16 2017 - JANUARY 27 2018 About the Curator Tony Godfrey came from Britain to Asia in 2009 and now lives and works in the Philippines as teacher, writer, and curator. For many years he ran the MA (Contemporary Art) at Sotheby’s Institute London. He has published books on contemporary art and his 1998 book, Conceptual Art, was the frst publication to see conceptual art as a global phenomenon. His 2009 book Painting Today also tried to survey paintings as a global phenomenon. He is currently working on books on the Balinese artist Mahendra Yasa and the Shanghai painter Ding Yi. CHANCE, PERFECTION, SIMPLE OR COMPLEX? I like art and I like owning art, but I have never been rich. However, in the Eighties and Nineties when conceptual artists like Jenny Holzer and John Baldessari made great t-shirts I could afford them. I hardly ever wore these two T-shirts by Gonzalez-Torres and Matthew Barney. I always wanted to use them in an exhibition like this because they seemed such polar opposites: simple and complex; minimal and maximal. Likewise, these two works by Byars and Tinguely seemed exemplars of perfection and chance in art – another polarity to find oneself between. As Tina had asked me to curate a show I sent this letter to eight artists whose work intrigued me and seemed appropriate: Pablo Capati III, Nona Garcia, Kawayan de Guia, Geraldine Javier, Nilo Ilarde. -

Learn English!

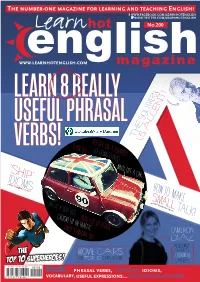

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS The number-one magazine for learning and teaching English! WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/LEARNHOTENGLISH WWW.TWITTER.COM/LEARNHOTENGLISH No.200 www.learnhotenglish.com LEARN 8 REALLY USEFUL PHRASAL SOUTHERN THE VERBS! SET OFF ON A JOURNEY US ACCENT! TURN OFF LET DOWN (TYRES) “SHIP WRITE OFF A C IDIOMS” AR HOW TO MAKE SMALL TALK! DO UP A S EAT BELT CAUGHT UP IN TRAFFRUN OUTIC OF PETROL DROP SOMEONE OFF CAMERON DIAZ THE HOLLYWOOD The STAR’S MOVIE CARS “COLOURFUL” Top 10 superheroes! OUR TOP 10 CARS IN FILMS. CAREER. ISSN 15777898 00200 PLUS… phrasal verbs, grammar, idioms, 9 771577 789001 vocabulary, useful expressions… and much, much more. РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS English Attention all Human Resource managers in Europe! Hot English Language Services offers language Classes training programmes that are guaranteed to improve ...for your employees! your employees’of English! level Hot English Language Services, a leader within the English company class training sector as well as an internationally-recognised publisher, has been offering language training solutions to many of the world's leading companies since 2001. A course with Hot English ensures: Motivated students thanks to our dynamic learning materials. Clear, measured progress through a structured system and monthly reports. Improvement in levels of English across the board. COURSES OFFERED: Dynamic telephone classes though our dedicated platform. Europe-wide courses through our extensive network. In-company groups and one-to-one classes. Practical business English classes and intensives. Specific industry courses: Finance, Medicine, Marketing, Human resources.. -

Matthew Ronay by David Pagel May 16, 2017

Review At Marc Foxx Gallery, the wild and whimsical world of Matthew Ronay By David Pagel May 16, 2017 Matthew Ronay, installation view, “Surds,” (Matthew Ronay and Marc Foxx) Matthew Ronay’s pint-sized sculptures strut their stuff like nothing else. The imagination races to catch up with the stories that spill from the New York artist’s evocative works at Marc Foxx Gallery, where nine candy-colored abstractions stand on cloth-draped pedestals and four yellow-hued doozies hang on the walls. Wild forest orchids and poison dart frogs come to mind — the first for their exotic beauty and fragile elegance, the second for their eye-popping colors and the dangers they signal. But a few moments in Ronay’s exhibition, “Surds,” buffer such extremes. To look closely at his playful pieces is to see the hand of a master craftsman at work, the mind of an original thinker at play and the heart of a generous giver doing his thing. Ronay’s sinuous forms are so carefully carved and lovingly sanded from chunks of basswood that you want to caress them like pets. The sense of friendliness is accentuated by the dyes Ronay has applied to his sculptures, leaving the wood grain visible and further softening their contours. Right angles and hard edges are nowhere to be found. Ronay’s sculptures look as if they might be the offspring of a pre- schooler’s building blocks and a rogue coral reef. Some parts of some sculptures have been coated with flocking, making their organic forms appear to be covered by a layer of unnatural moss, synthetic lichen or clothing.