1 Nancy Bird Walton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from Sir Reginald Ansett

LESSONS FROM SIR REGINALD ANSETT Reg Ansett became one of the wealthiest and most influential businessmen in Australia, with interests over a vast range of industries from television stations and air transport to credit card organisations. However, he would describe himself as an aviator. He was born in February 1909 in Inglewood, Victoria. His father owned a bicycle repair shop. When war broke out in 1914 his father enlisted and his mother and young Reg moved to Melbourne, settling in Camberwell. He left school at fourteen to find a job to help the family finances. He commenced work at a knitting factory becoming a highly-skilled sewing machine mechanic, until he was twenty-one. By then his dreams had been full of daring flight, particularly of his hero, Charles Kingsford Smith. He cashed in on an insurance policy to raise the funds for flying lessons and became the 419th Australian to be granted a licence. Unfortunately, at the time, the Depression was beginning to hurt the economy and opportunities for young pilots were limited. Showing his entrepreneurial spirit he decided that there was income to be made from growing peanuts in the Northern Territory, so he took a ship to Darwin. He soon realised it was not a well thought through plan and instead worked as an axeman clearing trees for surveyors. However, the experience in the vast distances of the Northern Territory confirmed to him that there was a great future in the transport business. He returned to Melbourne, purchased a second-hand Sudebaker car and decided to establish himself in the West of Victoria and began and taxi service from Hamilton to Ballarat. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN, FEBRUARY 22Nd 2016

District Governor: Jane Cox Assistant Governor: Lorraine Wilson President: Noel Howard. Tel: 0355724623. Mob. 0439311053 Email: [email protected] Secretary: Bob Penny. Tel: 0355711823 Email: [email protected] WEEKLY BULLETIN, FEBRUARY 22nd 2016 MEETING 3817 MEETING 3818 MONDAY 29th February 2016 WEDNESDAY 9th March 2016 Chair: Kevin Safe Chair: Program: Vocational visit to Hamilton Airport Program: Annual Bowls Challenge with H.N. at • IF YOU WEREN’T AT ROTARY ON MONDAY The Grangeburn Bowling Club. NIGHT, PLEASE LET KEVIN KNOW BY FRIDAY NIGHT IF YOU ARE COMING, AND IF YOU ARE BRINGING A PARTNER AND/OR A FRIEND. 55712790 Cashier: Glenn Howell ($15 pp) PARTNERS Cashier: Les Seiffert Bulletin: Rose Howard Bulletin: Rose Howard FOOD AND DRINK BYO Drinks & salad to share. Fines: None this week Fines: None this week Set up: Set up: Coming Dates March 9th (Wednesday) GRANGEBURN BOWLS CLUB March 15th Visit to Leo and Liz’s. PARTNERS NIGHT. March 23rd Combined Service Club meeting at Harness Racing Club. BYO Drink and a salad to share. 6pm. REPORT OF MEETING NO. 3816, February 22nd 2016. Chairman, Willis Duncan, opened the meeting with the Rotary Grace and the Loyal Toast. The International Toast was to the Rotary Club of Chicago Lakeview. It was chartered in September 2005. N.B. Rotary International was founded in Chicago 111 years ago on the 23rd February. President, Noel Howard, welcomed our guest speaker, Jim Ford. • Anniversary: Noel and Rose Howard • Induction Anniversary: Bob Penny • News from Fiji confirms that there was no damage to the RotaHomes project, from the recent Cyclone Winston. -

8 November 1966

2120 2120ASSEMBLY.] lowing his dependants to receive the lump sum that would have been payable to the worker had he lived. Tuesday, the 8th November, 1966 There have been cases of the worker dying and not receiving weekly payments, CONTENTS though this entitlement had accrued. The ANNUAL ESTIMATES, 1968-47- Page Workers' Compensation Board has been Coammlties of Supply *Votes and [teas Discussedi 2169 allowing these claims by dependants, al- though entertaining doubts in the matter. ASSENT TO BILLS..............2125 A provision has therefore been included BILLS- Fire Brigades Acl Amendment Bll-Assent ... 2125 to cover claims by dependants. where the Pluoridal ion of Publc Waler Supplie[s B2III-Retnrned 2125 worker's rights to weekly payments have Industrial Arbitration Aot Amendment Bill (No. 2)- Intro.; Ir. 22 existed for six months, although payments Public Service Acl Amendment Bil-.......22 have not been made during that period. Intro. ; Ir. ... .. ... 2 5 Public Service Appeal Board Act Amendment Bill- 22 The Bill also incorporates an alteration Intro.; Ir., .. .. .. - .. 2 2 in principle insomuch that the difference Public Service Arbitration rnB........22 in maximum payments between total and intro. ; Ir 1 .. .. .. 2125 Ptblic Works Act Amendment B111--Assent .. 2125 partial incapacity is removed. Payments Road and Air Transport Commissien Bili- for partial incapacity are at present limited Message : Appropriations.........2125 to a percentage of the amount paid for Slate Transport Ce-ordinatien Bill- 2r. ........................... 2127 total incapacity. Corn. 2155 The second schedule to the Act was re- Workers' Comrnsa [onAoct A mendment B II~ pealed and re-enacted In 1964, and fixes Report ; r.......... -

Charles Kingsford Smith, Known As

Significant People People Significant inAUSTRALIA’S HISTORY Contents in Significant People Significant People in Australia’s History profiles the people who brought HISTORY AUSTRALIA’S History makers 4 Boom times and the Great Depression 5 about important events or changes to Australian society through their in A snapshot of history 6 knowledge, actions or achievements. Explore the fascinating story of Australia, AUSTRALIA’S HISTORY Hudson Fysh, Pilot 8 from its ancient Indigenous past to the present day, through the biographies of Ross Smith and Keith Smith, Pilots 9 Raymond Longford and Lottie Lyell, Film stars 10 these significant people. Charles Bean, Journalist 12 Edith Cowan, Politician 14 Volume 6 Stanley Bruce, Prime Minister 16 Each volume focuses on a particular Special features include: Jimmy Clements, Indigenous leader 17 period in Australia’s history and includes: 6 Volume John Flynn, Religious leader 18 ‘life facts’ mini timeline Charles Kingsford Smith, Pilot 20 Life Facts background information about the of each person’s life Alf Traeger, Inventor 21 1580 Born in Holland 1920 –1938 featured time period and achievements 1615 Becomes commander 22 David Unaipon, Writer a timeline of main events of the Eendrach 1920 Grace Cossington Smith, Artist 23 1616 Lands on the western ‘more about …’ Morecoast about of Australia ... illustrated biographies of a wide range – Margaret Preston, Artist 24 information boxes Dirk Hartog1618 Island Returns to the 1938 Netherlands on the Jack Davey, Radio star 25 of significant people Hartog had landed in an area that was about related Eendrach home to the Malkana people, near Boom Times Don Bradman, Sportsperson 26 a glossary of terms * events and places modern-day Shark Bay in Western Australia. -

Australian Biography a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE australian biography a series that profiles some of the most extraordinary australians of our time nancy bird Walton 1915–2009 pioneer aviator This program is an episode of australian biography Series 1 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. australian biography: nancy bird Walton Director/producer Frank Heimans Executive producer Ron Saunders Duration 27 minutes year 1993 Study guide prepared by Kate Raynor © NFSA Also in Series 1: Neville Bonner, H.C. ‘Nugget’ Coombs, Dame Joan Hammond, Jack Hazlitt, Donald Horne, Sir Marcus Oliphant A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: NANCY BIRD WALTON 2 SYNOPSIS ∑ Do you think Nancy would be satisfied with the way the program represents her? In the early 1930s, aviation was opening up Australia and Nancy Bird began taking flying lessons at Charles Kingsford Smith’s Flying What do you think are Nancy’s strengths and weaknesses? School in Mascot. -

38159 BERB AUST TRADES.Indd

Catalogue 505 An Alphabetical Listing of Books pertaining to Australian Trades and Corporate Histories Offered subject to being unsold at net prices 1 ADAMS, WILLIAM & COMPANY LIMITED. The Bell- Wether. William Adams - an Australian Company from foundation to takeover - 1884 to 1984. Melbourne (1984). Sm.4to. Or.cl.d.w. (X,210pp.). With title-vign., num. text-illusts., and dec. end-papers. 1st ed. ADDED: Presentation letter dated 29th June, 1984 from Managing Director, loosely inserted. NOTE: William John Adams (1853-1935) an Englishman, fi rst came to Australia in 1883, and the following year he started a small engineering agency in Sydney. $55 2 ADELAIDE ELECTRIC SUPPLY CO. LTD: Fifty Years of Progress, 1896-1946. Being a History of the Foundation and Develop- ment of the Company. Adelaide (1947). 8vo. Or.cl. (viii,182pp.). With frontisp., num. plates, text-illusts., and map. Title-page printed in red/ black ink. $100 3 ADRIAN, C: Fighting Fire. A Century of Service, 1884-1984: (The Sydney and New South Wales Fire Brigades). Sydney (1984). Small 4to. Orig. cloth. Dustjacket. (272pp.). Profusely illust. in colour and b/w. Fine. $65 4 ADVERTISER, The. The South Australian Story. Published by Advertiser Newspapers Limited to mark the Centenary of The Advertiser 1858-1958. Adelaide: Griffi n Press, 1958. Small 4to. Orig. cloth. Gilt. (106pp.). With numerous plates, some of which are full-page, and illust. endpapers. Fine. $65 5 AIRD, W.V. (Compl. by). The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney. An account of the development and history of the water supply, sewerage and drainage systems of Sydney .. -

Feb. 2009 Flypaper .Cwk

The Flypaper The Official Newsletter of the Alaska 99s February 2009 Alaska Chapter 99s Officers Chair Gloria Tomich 279-1560 Notes from the Chair . Vice Chair Mio Johnson 696-3580 Secretary Calling All Ninety-Nines for the Melanie Hancock 694-4571 Treasurer February 11, 2009 Meeting Brenda Staats 522-5330 Committees Please plan to attend our regular monthly meeting, Scholarship Helen Jones 222-9977 February 11, at the UAA Aviation Technology Complex Room 245 at 5:30 PM. We will be introducing Flypaper Melanie Hancock 694-4571 ourselves to women students and Patty Livingston will Flying Companion give a presentation about the 99s and all the things we Angie Slingluff 337-0253 do as an organization. Brenda will talk about the Membership scholarships for this year and applications will be Mio Johnson 696-3580 distributed. Then we will enjoy pizza and sodas while Scrapbook socializing with the students. Any member planning to Lavelle Betz 243-1898 attend must RSVP to me ( HYPERLINK Airmarking Melanie Hancock 694-4571 "mailto:[email protected]" [email protected]) Aviation Museum Display or to Mio’s email announcement of this event so that we Pat Bening assure enough food for all. This event is open to ALL Sunshine women student pilots, not just those at UAA. If you Jean White 248-6967 know of any, please bring them along. Fly-Ins, & Publicity Committees need volunteers. If you have time to volunteer at the Alaska Air Carriers Association Annual Conference March 4 – 6, their organizing committee would be very grateful. There are many jobs to be done for a conference and even Next Meeting a short amount of volunteer time is helpful. -

Rex Law's Redline: the Biggest Little Bus Co. in Australia by Glenn a Law

A historical family/industry memoir describing the establishment and expansion of the Australian national road passenger transit/tourism industry. Includes the activities of the very early participants between the two world wars and those who took up the challenge to greatly expand the industry during the post WW2 generation through to 1970. Rex Law's Redline: The Biggest Little Bus Co. In Australia By Glenn A Law Order the book from the publisher Booklocker.com https://www.booklocker.com/p/books/11106.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Rex Law’s Redline THE BIGGEST LITTLE BUS CO IN AUSTRALIA Glenn A Law Saint Petersburg, Florida Copyright © 2020 Glenn A Law ISBN: 978-1-64718-388-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2020 First Edition Cover photograph: Two Redline touring coaches pictured in Central Australia in 1963 at the base of Ayers Rock, (Uluru) the world’s largest natural rock monolith. Adventurous tourists can be seen climbing to the summit, 348 metres (1142 feet) above the surrounding desert. (Laurie MacBeth Collection) For permission requests, write to the publisher, headed “Permissions Request,” at — [email protected] Book Layout ©2019 BookDesignTemplates.com Ordering Information: Quantity sales: Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corpora- tions, associations and others. -

ACI World Airport Development News: Issue 01 – 2020

Issue 01 / 2020 ACI World AIRPORT DEVELOPMENT NEWS A service provided by ACI World in cooperation with Momberger Airport Information www.mombergerairport.info Editor & Publisher: Martin Lamprecht [email protected] Founding Editor & Publisher: Manfred Momberger Contents Focus on Oceania ............................................................................................................. 1 Other Regions .................................................................................................................... 6 Green Airports ................................................................................................................... 7 Focus on Oceania AUSTRALIA Initial design concepts have been unveiled for Western Sydney International Airport (‘Nancy-Bird Walton Airport’) by the international firm Zaha Hadid Architects and Australia’s Cox Architecture, which were selected to design the state-of-the-art terminal precinct. The brief was to design an airport that the people of Western Sydney can be proud of. The exterior of the terminal complements the natural landscape, paying tribute to the local area. Arriving passengers will be greeted by landscaped gardens within a grand public plaza with a great choice of retail, dining and entertainment. When they enter the terminal, the lighting and curvature of the soaring timber ceilings will help to guide them through the building while stunning vertical gardens will provide an inviting and relaxing start to their journey. Western Sydney University students and -

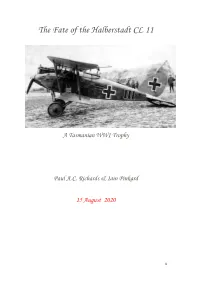

The Fate of the Halberstadt CL 11

The Fate of the Halberstadt CL 11 A Tasmanian WW1 Trophy Paul A.C. Richards & Iain Pinkard 15 August 2020 1 2 _____________________________ The Fate of the Halberstadt CL 11 A Tasmanian WW1 Trophy ________________________________________ Paul A.C. Richards AM and Iain Pinkard 3 First uploaded to TAHS Website August 2020 By Paul A.C. Richards First published in XXXXXX in an edition of 100 copies Typeset in 11pt New Times Roman Printed by Foot & Playsted, Launceston, Tasmania 7250 Book designed by Paul A.C. Richards All rights reserved. Apart from use permitted under the Copyright Act of 1968 and its amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Available from XXXXXXXXXXXXX National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Aviation History Includes Index & End Notes ISBN Educational / Biographical 1-Paul A.C. Richards AM, 2- Iain Pinkard Principal Editor, Lisa Jones 4 CONTENTS Page Introduction 6 Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Chapter 1 No3 Squadron Australian Flying Corps 9 Chapter 2 Tasmanian War Trophies 17 Chapter 3 The Halebertstadt CL 11 27 Chapter 4 Fate of the Halbertstadt CL 11 39 Chapter 5 Tasmanian Aviation Pioneers 45 Chapter 6 Vale’s Aeroplane 63 Chapter 7 Tasmanian Aero Club and Tasmanian Airline Services 1930s 65 Chapter 8 The Holyman’s 71 Appendix 79 About the Authors 95 5 Introduction In June 1918 at Flesselles1 a German Halberstadt CL II Aircraft, number 15342/17 was forced to land by Lieutenants Armstrong and Mart of No 3 Squadron Australian Flying Corps. -

Planning for Australia's Future Population

Planning for Australia’s Future Population September 2019 Planning for Australia’s Future Population Contents From the Prime Minister 5 From the Minister for Population, Cities and Urban Infrastructure 7 Planning for Australia’s future population 8 Taking action to manage Australia’s changing population 10 Working with State, Territory and Local governments 12 Better understanding population changes 13 Australia’s population story 14 The origins of a growing Australia 16 Strong population growth in cities 18 Taking the pressure off cities 20 Commonwealth infrastructure investment 22 Busting congestion in cities 23 Targeted investment to drive urban development 26 Connecting regional centres 28 Delivering a prosperous Australia 30 Housing for a growing population 32 Supporting a changing population 34 Delivering the skills needed in regions 36 Investing in regional Australia 38 Keeping Australians together 40 Supporting migrants to adapt to life in Australia 42 4 PLANNING FOR AUSTRALIA’S FUTURE POPULATION From the Prime Minister There is so much that is great about our country. We are a stable, prosperous and peaceful nation. But this doesn’t mean we can be complacent. We cannot ignore the big issues in the hope they will solve themselves. One of these big issues is population. Everyone has a view on what Australia should look like in the future. But I think that all of those views would include new infrastructure and better services. They would include a safe Australia, where jobs are plentiful and opportunities abound. An Australia that welcomes new migrants but ensures we choose who joins us. An Australia where people can afford a home for their families and be well enough off to give them what they need. -

Nancy Bird Walton Australia’S Pioneering Aviatrix

Nancy Bird Walton Australia’s Pioneering Aviatrix around the country, going to local agricul- “Life was meant tural shows and charging for joy flights. Nancy was often told by the guys that there to be flown.” was no room for women in aviation, barn- storming had been “done to death” and men were finding aviation a struggle. But BY CAROL KITCHING, Guest Author she was determined. Nancy figured she needed a co-pilot if this plan were to ma- At the tender age of 92, Nancy Bird terialize, and Peggy McKillop fitted the Walton, Australia’s premier woman pilot, bill. Perfectly. Peggy had a pilot’s license, still gets excited about flying. In 1933, she’d trained at the same time as Nancy Awhen she was 17, she made the decision and she was a bit of a whiz at aircraft en- that life was meant to be flown, and today gines and mending torn fabric. her interests revolve around aviation. In In 1935 the two girls formed The First recognizing her contribution to the indus- Ladies Flying Tour, and off they went try, Quantas announced it will name its first around New South Wales, flying into coun- A380 after her. Nancy Bird will be flying try paddocks to do joy flights and attend- for many years to come. ing the occasional country show or ball. As a young girl, her dreams were Peggy McKillop as Big Bird and Nancy about flying. “When I had nightmares and as Little Bird (with pillow) flew into his- tigers and lions were chasing me, I could tory as the country’s first female barn- lift myself above them...and they’d run Nancy Bird is first aboard the new Airbus stormers.