Interview with Dr Kaarina Aitamurto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploration of a DDC/UDC View of Religion

EPC Exhibit 134-11.3 May 12, 2011 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Dewey Section To: Caroline Kent, Chair Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Cc: Members of the Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Karl E. Debus-López, Chief, U.S. General Division From: Giles Martin, Assistant Editor Dewey Decimal Classification OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc Re: Chronological/regional view of 200 Religion For some time now we have been exploring the development of an alternative view of 200 Religion to reduce the perceived Christian bias in the standard notational sequence for religions in 200. The UDC 2 Religion schedule, revised in 2000, includes a chronological/regional view of religion that is a promising model for such an alternative arrangement. Much of the work on this has been done by Ia McIlwaine (formerly the editor-in-chief of the Universal Decimal Classification – UDC) and Joan Mitchell. I have attached a paper that they presented on the subject as Appendix 2 to this exhibit. The paper’s citation is: McIlwaine, Ia, and Joan S. Mitchell. 2006. ―The New Ecumenism: Exploration of a DDC/UDC View of Religion.‖ In Knowledge Organization for a Global Learning Society: Proceedings of the 9th International ISKO Conference, 4-7 July 2006, Vienna, Austria, edited by Gerhard Budin, Christian Swertz, and Konstantin Mitgutsch, p. 323-330. Würzberg: Ergon. I have also attached a top-level summary of the arrangement of religions and sects in UDC 2 Religion as Appendix 1. As can be seen in Appendix 1, at the top level UDC uses three principles of arrangement: (1) It generally arranges religions chronologically in order of the foundation of the world’s major religions, though the grouping at 25 (Religions of antiquity. -

The Problem of Mysteriousness of Baba Yaga Character in Religious Mythology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 12 (2013 6) 1857-1866 ~ ~ ~ УДК 7.046 The Problem of Mysteriousness of Baba Yaga Character in Religious Mythology Evgenia V. Ivanova* Ural Federal University named after B.N. Yeltsin 51 Lenina, Ekaterinburg, 620083 Russia Received 28.07.2013, received in revised form 30.09.2013, accepted 05.11.2013 This article reveals the ambiguity of interpretation of Baba Yaga character by the representatives of different schools of mythology. Each of the researchers has his own version of the semantic peculiarities of this culture hero. Who is she? A pagan goddess, a priestess of pagan goddesses, a witch, a snake or a nature-deity? The aim of this research is to reveal the ambiguity of the archetypical features of this character and prove that the character of Baba Yaga as a culture hero of the archaic religious mythology has an influence on the contemporary religious mythology of mass media. Keywords: religious mythology, myth, culture hero, paganism, symbol, fairytale, religion, ritual, pagan priestess. Introduction. “Religious mythology” is examined by the author of the article (Ivanova, a new term, which is relevant to contemporary 2012, p.56). The subject of the research presented religious and cultural studies, philosophy in this article is topography or conceptual space of religion and other sciences focusing on of notional understanding of the fairytale pagan correlation between myth and religion. This culture hero – the character of Baba Yaga. -

The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature

From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Dorian Townsend Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales May 2011 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Townsend First name: Dorian Other name/s: Aleksandra PhD, Russian Studies Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Languages and Linguistics Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The Slavic vampire myth traces back to pre-Orthodox folk belief, serving both as an explanation of death and as the physical embodiment of the tragedies exacted on the community. The symbol’s broad ability to personify tragic events created a versatile system of imagery that transcended its folkloric derivations into the realm of Russian literature, becoming a constant literary device from eighteenth century to post-Soviet fiction. The vampire’s literary usage arose during and after the reign of Catherine the Great and continued into each politically turbulent time that followed. The authors examined in this thesis, Afanasiev, Gogol, Bulgakov, and Lukyanenko, each depicted the issues and internal turmoil experienced in Russia during their respective times. By employing the common mythos of the vampire, the issues suggested within the literature are presented indirectly to the readers giving literary life to pressing societal dilemmas. The purpose of this thesis is to ascertain the vampire’s function within Russian literary societal criticism by first identifying the shifts in imagery in the selected Russian vampiric works, then examining how the shifts relate to the societal changes of the different time periods. -

Is Modern Paganism True?

KRONMAN FINAL TO PRINT (1).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/13/2019 1:40 PM Is Modern Paganism True? ANTHONY T. KRONMAN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 419 II. PROGRESSIVE PAGANS? ........................................................................... 422 III. ARISTOTLE .............................................................................................. 427 IV. PAGANS AND CHRISTIANS ........................................................................ 436 V. A THIRD THEOLOGY ................................................................................ 438 VI. THE TRUTH ABOUT GOD?............................................................. ........... 443 VII. CONCLUSION ........................................................................................... 447 I. INTRODUCTION I agree with so much in Steven Smith’s splendid new book1 that it seems ungenerous to focus, as I shall, on the principal disagreement between us. But the disagreement is an important one. It goes to the heart of the question Smith raises in the final pages of his book: which has more “religious truth,” Christianity or modern paganism?2 Before I examine our theological differences, it is important to note a few of the political, legal, and constitutional points on which Smith and I agree. In practical terms these are surely more important than the theological subtleties that distinguish his understanding of God from mine. So far as worldly matters are concerned, -

PAGANISM a Brief Overview of the History of Paganism the Term Pagan Comes from the Latin Paganus Which Refers to Those Who Lived in the Country

PAGANISM A brief overview of the history of Paganism The term Pagan comes from the Latin paganus which refers to those who lived in the country. When Christianity began to grow in the Roman Empire, it did so at first primarily in the cities. The people who lived in the country and who continued to believe in “the old ways” came to be known as pagans. Pagans have been broadly defined as anyone involved in any religious act, practice, or ceremony which is not Christian. Jews and Muslims also use the term to refer to anyone outside their religion. Some define paganism as a religion outside of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism; others simply define it as being without a religion. Paganism, however, often is not identified as a traditional religion per se because it does not have any official doctrine; however, it has some common characteristics within its variety of traditions. One of the common beliefs is the divine presence in nature and the reverence for the natural order in life. In the strictest sense, paganism refers to the authentic religions of ancient Greece and Rome and the surrounding areas. The pagans usually had a polytheistic belief in many gods but only one, which represents the chief god and supreme godhead, is chosen to worship. The Renaissance of the 1500s reintroduced the ancient Greek concepts of Paganism. Pagan symbols and traditions entered European art, music, literature, and ethics. The Reformation of the 1600s, however, put a temporary halt to Pagan thinking. Greek and Roman classics, with their focus on Paganism, were accepted again during the Enlightenment of the 1700s. -

Panama's Dollarized Economy Mainly Depends on a Well-Developed Services Sector That Accounts for 80 Percent of GDP

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM - PROGRAMA LATINOAMERICANO DE ESTUDIOS SOCIORRELIGIOSOS (PROLADES) ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: RELIGION IN PANAMA SECOND EDITION By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES Last revised on 3 November 2020 PROLADES Apartado 86-5000, Liberia, Guanacaste, Costa Rica Telephone (506) 8820-7023; E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com/ ©2020 Clifton L. Holland, PROLADES 2 CONTENTS Country Summary 5 Status of Religious Affiliation 6 Overview of Panama’s Social and Political Development 7 The Roman Catholic Church 12 The Protestant Movement 17 Other Religions 67 Non-Religious Population 79 Sources 81 3 4 Religion in Panama Country Summary Although the Republic of Panama, which is about the size of South Carolina, is now considered part of the Central American region, until 1903 the territory was a province of Colombia. The Republic of Panama forms the narrowest part of the isthmus and is located between Costa Rica to the west and Colombia to the east. The Caribbean Sea borders the northern coast of Panama, and the Pacific Ocean borders the southern coast. Panama City is the nation’s capital and its largest city with an urban population of 880,691 in 2010, with over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal , and is the political and administrative center of the country, as well as a hub for banking and commerce. The country has an area of 30,193 square miles (75,417 sq km) and a population of 3,661,868 (2013 census) distributed among 10 provinces (see map below). -

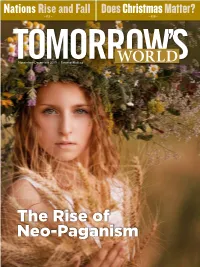

The Rise of Neo-Paganism a Personal Message from the Editor in Chief

Nations Rise and Fall Does Christmas Matter? — P. 5 — — P. 18 — November-December 2019 | TomorrowsWorld.org The Rise of Neo-Paganism A personal message from the Editor in Chief How Can All of This Be Free? here are two of our resources that you this gospel of the kingdom will be preached in all the have not likely come across. Frankly, I do world as a witness to all the nations, and then the end not think we have advertised them to the will come” (Matthew 24:14). public or mentioned them in our maga- As you well know, we never request donations on zineT in years. Do you know what they are? the Tomorrow’s World telecast, in our magazine, or in This column is titled “Personal” for a reason. As any of our literature. Coworkers and members of the Editor in Chief, it gives me an opportunity to com- Living Church of God take seriously Jesus’ admoni- municate with you about those things that are on my tion, “Freely you have received, freely give” (Matthew mind, and in this issue, I want to answer three ques- 10:8). Or as Proverbs 23 tells us, “Buy the truth, and tions that are asked of us: “Who is behind Tomorrow’s do not sell it” (v. 23). World?,” “Is it really free?,” and “How can you pay for so much television and give away all of your materials A Different Approach without asking for money?” Of the more than 290,000 current subscribers to Let me answer the second question first. -

Paganism.Pdf

Pagan Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Author .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Beliefs, Teachings, Wisdom and Authority ....................................................................................................................... 2 Basic Beliefs ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Sources of Authority and (lack of) scriptures ........................................................................................................................ 4 Founders and Exemplars ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ways of Living ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Guidance for life .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ritual practice ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

New Religions in Global Perspective

New Religions in Global Perspective New Religions in Global Perspective is a fresh in-depth account of new religious movements, and of new forms of spirituality from a global vantage point. Ranging from North America and Europe to Japan, Latin America, South Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, this book provides students with a complete introduction to NRMs such as Falun Gong, Aum Shinrikyo, the Brahma Kumaris movement, the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood, Sufism, the Engaged Buddhist and Neo-Hindu movements, Messianic Judaism, and African diaspora movements including Rastafarianism. Peter Clarke explores the innovative character of new religious movements, charting their cultural significance and global impact, and how various religious traditions are shaping, rather than displacing, each other’s understanding of notions such as transcendence and faith, good and evil, of the meaning, purpose and function of religion, and of religious belonging. In addition to exploring the responses of governments, churches, the media and general public to new religious movements, Clarke examines the reactions to older, increasingly influential religions, such as Buddhism and Islam, in new geographical and cultural contexts. Taking into account the degree of continuity between old and new religions, each chapter contains not only an account of the rise of the NRMs and new forms of spirituality in a particular region, but also an overview of change in the regions’ mainstream religions. Peter Clarke is Professor Emeritus of the History and Sociology of Religion at King’s College, University of London, and a professorial member of the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford. Among his publications are (with Peter Byrne) Religion Defined and Explained (1993) and Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective (ed.) (2000). -

True History of Christianity Part1

““JohnJohn SmithSmith”” TheThe TrueTrue HistoryHistory ofof ChristianityChristianity LLet him who seeks continue seeking until he finds. When he finds, he will become troubled. When he becomes troubled, he will be astonished ... Jesus said ... For nothing hidden will not become manifest, and nothing covered will remain without being uncovered. The apocryphal Gospel of Thomas, a 4th Century ‘heretical’ text discovered at Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945. MMany others, who oppose the truth and are the messengers of error, will set up their error ... thinking that good and evil are from one (source) ... but those of this sort will be cast into the outer darkness. From the Apocalypse of Peter, also found at Nag Hammadi. “Jesus said, ... For there are five trees for you in Paradise which remain undisturbed summer and winter and whose leaves do not fall. Whoever becomes acquainted with them will not experience death”. The apocryphal Gospel of Thomas II:19, also found at Nag Hammadi. The True History of Christianity “John Smith” 2005 4 The True History of Christianity DEDICATIONS This book is dedicated to a number of individuals who played an important part in this project - Firstly, no greater thanks can go to my family who patiently waited 10 years while their dad finished this book, and to my folks for their assistance when the going was really tough. Thanks also to the idiot who undid my wheel nuts (almost wiping out an entire family), not to mention the vile piece of of filth who cut through my brake hose causing my vehicle to spin out of control. -

ESSWE Newsletter: I Hope the Member’S Book Showcase, As by Now Is Usual, Occupies More You Are All Keeping Safe and Healthy

The Newsletter of the ESSWE European Society for Summer 2020 the Study of Western Volume 11, Number 1 Esotericism Newsletter Words from the Editor – Chris Giudice Words from the Editor (p. 1) New Publications (p. 2) Scholar Interviews (p. 3) New Sub-Networks (p. 9) Conference Reports (p. 10) Upcoming Conferences (p. 12) Welcome to the summer issue of the ESSWE newsletter: I hope The member’s book showcase, as by now is usual, occupies more you are all keeping safe and healthy. In this issue, for obvious than one page, and it’s a pleasure to see the field of Western reasons, there will be no reviews of past conferences, but I have esotericism blossoming and making its presence felt in many balanced the lack of conference write-ups with more book reviews different fields, through the interdisciplinary approach of many and upcoming events, which I hope we will all be able to attend in authors. As to the scholar interviews, this time I wanted to 2021. The call for papers for the 8th ESSWE is out, and it will be highlight the work in the field by Zurich’s ETH: therefore wonderful to meet you all in Cork, where the wide-ranging theme Professor Andreas Kilcher and PhD scholar Chloë Sugden have of ‘Western esotericism and Creativity’ will surely be tackled in been kind enough to provide me with very interesting answers. many different ways. A special message by the president of Hope you are all enjoying your summer and that we will all be ESSWE can be found on page 2, along with all the new dates for able to reconvene in Cork in 10 months’ time! ♦ future ESSWE activities. -

A Reader in Comparative Indo-European Religion

2018 A READER IN COMPARATIVE INDO-EUROPEAN RELIGION Ranko Matasović Zagreb 2018 © This publication is intended primarily for the use of students of the University of Zagreb. It should not be copied or otherwise reproduced without a permission from the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................................................ Foreword............................................................................................................................... PART 1: Elements of the Proto-Indo-European religion...................................................... 1. Reconstruction of PIE religious vocabulary and phraseology................................... 2. Basic Religious terminology of PIE.......................................................................... 3. Elements of PIE mythology....................................................................................... PART II: A selection of texts Hittite....................................................................................................................................... Vedic........................................................................................................................................ Iranian....................................................................................................................................... Greek.......................................................................................................................................