Is Modern Paganism True?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploration of a DDC/UDC View of Religion

EPC Exhibit 134-11.3 May 12, 2011 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Dewey Section To: Caroline Kent, Chair Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Cc: Members of the Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Karl E. Debus-López, Chief, U.S. General Division From: Giles Martin, Assistant Editor Dewey Decimal Classification OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc Re: Chronological/regional view of 200 Religion For some time now we have been exploring the development of an alternative view of 200 Religion to reduce the perceived Christian bias in the standard notational sequence for religions in 200. The UDC 2 Religion schedule, revised in 2000, includes a chronological/regional view of religion that is a promising model for such an alternative arrangement. Much of the work on this has been done by Ia McIlwaine (formerly the editor-in-chief of the Universal Decimal Classification – UDC) and Joan Mitchell. I have attached a paper that they presented on the subject as Appendix 2 to this exhibit. The paper’s citation is: McIlwaine, Ia, and Joan S. Mitchell. 2006. ―The New Ecumenism: Exploration of a DDC/UDC View of Religion.‖ In Knowledge Organization for a Global Learning Society: Proceedings of the 9th International ISKO Conference, 4-7 July 2006, Vienna, Austria, edited by Gerhard Budin, Christian Swertz, and Konstantin Mitgutsch, p. 323-330. Würzberg: Ergon. I have also attached a top-level summary of the arrangement of religions and sects in UDC 2 Religion as Appendix 1. As can be seen in Appendix 1, at the top level UDC uses three principles of arrangement: (1) It generally arranges religions chronologically in order of the foundation of the world’s major religions, though the grouping at 25 (Religions of antiquity. -

PAGANISM a Brief Overview of the History of Paganism the Term Pagan Comes from the Latin Paganus Which Refers to Those Who Lived in the Country

PAGANISM A brief overview of the history of Paganism The term Pagan comes from the Latin paganus which refers to those who lived in the country. When Christianity began to grow in the Roman Empire, it did so at first primarily in the cities. The people who lived in the country and who continued to believe in “the old ways” came to be known as pagans. Pagans have been broadly defined as anyone involved in any religious act, practice, or ceremony which is not Christian. Jews and Muslims also use the term to refer to anyone outside their religion. Some define paganism as a religion outside of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism; others simply define it as being without a religion. Paganism, however, often is not identified as a traditional religion per se because it does not have any official doctrine; however, it has some common characteristics within its variety of traditions. One of the common beliefs is the divine presence in nature and the reverence for the natural order in life. In the strictest sense, paganism refers to the authentic religions of ancient Greece and Rome and the surrounding areas. The pagans usually had a polytheistic belief in many gods but only one, which represents the chief god and supreme godhead, is chosen to worship. The Renaissance of the 1500s reintroduced the ancient Greek concepts of Paganism. Pagan symbols and traditions entered European art, music, literature, and ethics. The Reformation of the 1600s, however, put a temporary halt to Pagan thinking. Greek and Roman classics, with their focus on Paganism, were accepted again during the Enlightenment of the 1700s. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Mithras and Mithraism Citation for published version: Sauer, E 2012, 'Mithras and Mithraism: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History', The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, pp. 4551-4553. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17273 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17273 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History Publisher Rights Statement: © Sauer, E. (2012). Mithras and Mithraism: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, 4551-4553 doi: 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17273 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 © Sauer, E. (2012). Mithras and Mithraism: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, 4551-4553 doi: 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17273 Mithras and Mithraism By Eberhard Sauer, University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Worshipped in windowless cave-like temples or natural caves, across the Roman Empire by exclusively male (Clauss 1992; Griffith 2006) congregations, few ancient deities have aroused more curiosity than the sun god Mithras. -

Paganism and Neo-Paganism Practiced by the Reformed Druids of North America Is Neo-Pagan

RT1806_P.qxd 1/30/2004 3:35 PM Page 307 P Paganism and Neo-Paganism practiced by the Reformed Druids of North America is Neo-Pagan. Paganism and Neo-Paganism are religions that prac- Contemporary Neo-Pagan traditions are diverse tice, reclaim, or experiment with non- and pre- and include groups who reclaim ancient Sumerian, Christian forms of worship. The term pagan, from Egyptian, Greek, and Roman practices as well as the Latin word paganus (country dweller), was used those dedicated to reviving Druidism (the priest- by early Christians to describe what they saw as hood of the ancient Gauls) and the worship of Norse the backward, unsophisticated practices of rural peo- gods and goddesses. Traditions also include her- ple who continued to worship Roman gods after metic (relating to the works attributed to Hermes Christianity had been declared the official religion of Trismegistus) groups such as the Ordo Templo the Roman Empire in 415 CE. The term maintained a Orientis (OTO), an occult society founded in negative connotation until it was reclaimed by Germany in the late 1800s to the revive magic and Romantic (relating to a literary, artistic, and philo- mysticism; cabalistic groups who study ancient sophical movement originating in the eighteenth Hebrew mysticism; and alchemists, who practice the century) revivalists in nineteenth-century Europe. spiritual refinement of the will. By far the largest sub- Inspired by the works of early anthropologists and group within Neo-Paganism is made up of revival folklorists, who attributed spiritual authenticity to witchcraft traditions, including Wicca (revival witch- pre-Christian Europeans and the indigenous people craft). -

Panama's Dollarized Economy Mainly Depends on a Well-Developed Services Sector That Accounts for 80 Percent of GDP

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM - PROGRAMA LATINOAMERICANO DE ESTUDIOS SOCIORRELIGIOSOS (PROLADES) ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: RELIGION IN PANAMA SECOND EDITION By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES Last revised on 3 November 2020 PROLADES Apartado 86-5000, Liberia, Guanacaste, Costa Rica Telephone (506) 8820-7023; E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com/ ©2020 Clifton L. Holland, PROLADES 2 CONTENTS Country Summary 5 Status of Religious Affiliation 6 Overview of Panama’s Social and Political Development 7 The Roman Catholic Church 12 The Protestant Movement 17 Other Religions 67 Non-Religious Population 79 Sources 81 3 4 Religion in Panama Country Summary Although the Republic of Panama, which is about the size of South Carolina, is now considered part of the Central American region, until 1903 the territory was a province of Colombia. The Republic of Panama forms the narrowest part of the isthmus and is located between Costa Rica to the west and Colombia to the east. The Caribbean Sea borders the northern coast of Panama, and the Pacific Ocean borders the southern coast. Panama City is the nation’s capital and its largest city with an urban population of 880,691 in 2010, with over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal , and is the political and administrative center of the country, as well as a hub for banking and commerce. The country has an area of 30,193 square miles (75,417 sq km) and a population of 3,661,868 (2013 census) distributed among 10 provinces (see map below). -

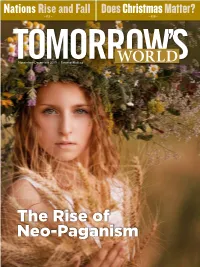

The Rise of Neo-Paganism a Personal Message from the Editor in Chief

Nations Rise and Fall Does Christmas Matter? — P. 5 — — P. 18 — November-December 2019 | TomorrowsWorld.org The Rise of Neo-Paganism A personal message from the Editor in Chief How Can All of This Be Free? here are two of our resources that you this gospel of the kingdom will be preached in all the have not likely come across. Frankly, I do world as a witness to all the nations, and then the end not think we have advertised them to the will come” (Matthew 24:14). public or mentioned them in our maga- As you well know, we never request donations on zineT in years. Do you know what they are? the Tomorrow’s World telecast, in our magazine, or in This column is titled “Personal” for a reason. As any of our literature. Coworkers and members of the Editor in Chief, it gives me an opportunity to com- Living Church of God take seriously Jesus’ admoni- municate with you about those things that are on my tion, “Freely you have received, freely give” (Matthew mind, and in this issue, I want to answer three ques- 10:8). Or as Proverbs 23 tells us, “Buy the truth, and tions that are asked of us: “Who is behind Tomorrow’s do not sell it” (v. 23). World?,” “Is it really free?,” and “How can you pay for so much television and give away all of your materials A Different Approach without asking for money?” Of the more than 290,000 current subscribers to Let me answer the second question first. -

Read Book Religion in the Ancient Greek City 1St Edition Kindle

RELIGION IN THE ANCIENT GREEK CITY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Louise Bruit Zaidman | 9780521423571 | | | | | Religion in the Ancient Greek City 1st edition PDF Book Altogether the year in Athens included some days that were religious festivals of some sort, though varying greatly in importance. Some of these mysteries, like the mysteries of Eleusis and Samothrace , were ancient and local. Athens Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. At some date, Zeus and other deities were identified locally with heroes and heroines from the Homeric poems and called by such names as Zeus Agamemnon. The temple was the house of the deity it was dedicated to, who in some sense resided in the cult image in the cella or main room inside, normally facing the only door. Historical religions. Christianization of saints and feasts Christianity and Paganism Constantinian shift Hellenistic religion Iconoclasm Neoplatonism Religio licita Virtuous pagan. Sacred Islands. See Article History. Sim Lyriti rated it it was amazing Mar 03, Priests simply looked after cults; they did not constitute a clergy , and there were no sacred books. I much prefer Price's text for many reasons. At times certain gods would be opposed to others, and they would try to outdo each other. An unintended consequence since the Greeks were monogamous was that Zeus in particular became markedly polygamous. Plato's disciple, Aristotle , also disagreed that polytheistic deities existed, because he could not find enough empirical evidence for it. Once established there in a conspicuous position, the Olympians came to be identified with local deities and to be assigned as consorts to the local god or goddess. -

Scourging Paganism Past and Present: the Tragic Irony of Palmyra Written by Robert A

Scourging Paganism Past and Present: The Tragic Irony of Palmyra Written by Robert A. Saunders This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Scourging Paganism Past and Present: The Tragic Irony of Palmyra https://www.e-ir.info/2015/05/28/scourging-paganism-past-and-present-the-tragic-irony-of-palmyra/ ROBERT A. SAUNDERS, MAY 28 2015 Over the past several days I have been somewhat perplexed, if not perturbed by the news media coverage of the impending destruction of pagan sites, particularly the iconic Temple of Baal and later Roman ruins, at Palmyra in ISIL- occupied Syrian territory. If the destruction of these sites does take place, it will continue ISIL’s carefully calculated strategy of publicly and performatively erasing pagan history from the Islamic Middle East. On Euronews, BBC World, and other international media (including Catholic media outlets), a familiar refrain has emerged among (mostly European) commentators, including representatives of UNESCO, bemoaning ISIL’s architecture-razing rampage in Nimrud and elsewhere as ‘cultural genocide’, and affront to the very foundations of Western civilisation. However, there is a bitter irony at work here, particularly when one focuses a critical gaze upon how we engage with historical memory, the idea of Europe, and the notions of cultural and religious ‘cleansing’. By all accounts, the medieval knitting together of Europe under the Emperor Charlemagne serves as the historical basis of what we today call ‘Western civilization’ by initiating a return to the transnational integration that had once characterised the Roman Empire. -

Paganism.Pdf

Pagan Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Author .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Beliefs, Teachings, Wisdom and Authority ....................................................................................................................... 2 Basic Beliefs ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Sources of Authority and (lack of) scriptures ........................................................................................................................ 4 Founders and Exemplars ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ways of Living ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Guidance for life .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ritual practice ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

New Religions in Global Perspective

New Religions in Global Perspective New Religions in Global Perspective is a fresh in-depth account of new religious movements, and of new forms of spirituality from a global vantage point. Ranging from North America and Europe to Japan, Latin America, South Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, this book provides students with a complete introduction to NRMs such as Falun Gong, Aum Shinrikyo, the Brahma Kumaris movement, the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood, Sufism, the Engaged Buddhist and Neo-Hindu movements, Messianic Judaism, and African diaspora movements including Rastafarianism. Peter Clarke explores the innovative character of new religious movements, charting their cultural significance and global impact, and how various religious traditions are shaping, rather than displacing, each other’s understanding of notions such as transcendence and faith, good and evil, of the meaning, purpose and function of religion, and of religious belonging. In addition to exploring the responses of governments, churches, the media and general public to new religious movements, Clarke examines the reactions to older, increasingly influential religions, such as Buddhism and Islam, in new geographical and cultural contexts. Taking into account the degree of continuity between old and new religions, each chapter contains not only an account of the rise of the NRMs and new forms of spirituality in a particular region, but also an overview of change in the regions’ mainstream religions. Peter Clarke is Professor Emeritus of the History and Sociology of Religion at King’s College, University of London, and a professorial member of the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford. Among his publications are (with Peter Byrne) Religion Defined and Explained (1993) and Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective (ed.) (2000). -

ESSWE Newsletter: I Hope the Member’S Book Showcase, As by Now Is Usual, Occupies More You Are All Keeping Safe and Healthy

The Newsletter of the ESSWE European Society for Summer 2020 the Study of Western Volume 11, Number 1 Esotericism Newsletter Words from the Editor – Chris Giudice Words from the Editor (p. 1) New Publications (p. 2) Scholar Interviews (p. 3) New Sub-Networks (p. 9) Conference Reports (p. 10) Upcoming Conferences (p. 12) Welcome to the summer issue of the ESSWE newsletter: I hope The member’s book showcase, as by now is usual, occupies more you are all keeping safe and healthy. In this issue, for obvious than one page, and it’s a pleasure to see the field of Western reasons, there will be no reviews of past conferences, but I have esotericism blossoming and making its presence felt in many balanced the lack of conference write-ups with more book reviews different fields, through the interdisciplinary approach of many and upcoming events, which I hope we will all be able to attend in authors. As to the scholar interviews, this time I wanted to 2021. The call for papers for the 8th ESSWE is out, and it will be highlight the work in the field by Zurich’s ETH: therefore wonderful to meet you all in Cork, where the wide-ranging theme Professor Andreas Kilcher and PhD scholar Chloë Sugden have of ‘Western esotericism and Creativity’ will surely be tackled in been kind enough to provide me with very interesting answers. many different ways. A special message by the president of Hope you are all enjoying your summer and that we will all be ESSWE can be found on page 2, along with all the new dates for able to reconvene in Cork in 10 months’ time! ♦ future ESSWE activities. -

Slavic Pagan World

Slavic Pagan World 1 Slavic Pagan World Compilation by Garry Green Welcome to Slavic Pagan World: Slavic Pagan Beliefs, Gods, Myths, Recipes, Magic, Spells, Divinations, Remedies, Songs. 2 Table of Content Slavic Pagan Beliefs 5 Slavic neighbors. 5 Dualism & The Origins of Slavic Belief 6 The Elements 6 Totems 7 Creation Myths 8 The World Tree. 10 Origin of Witchcraft - a story 11 Slavic pagan calendar and festivals 11 A small dictionary of slavic pagan gods & goddesses 15 Slavic Ritual Recipes 20 An Ancient Slavic Herbal 23 Slavic Magick & Folk Medicine 29 Divinations 34 Remedies 39 Slavic Pagan Holidays 45 Slavic Gods & Goddesses 58 Slavic Pagan Songs 82 Organised pagan cult in Kievan Rus' 89 Introduction 89 Selected deities and concepts in slavic religion 92 Personification and anthropomorphisation 108 "Core" concepts and gods in slavonic cosmology 110 3 Evolution of the eastern slavic beliefs 111 Foreign influence on slavic religion 112 Conclusion 119 Pagan ages in Poland 120 Polish Supernatural Spirits 120 Polish Folk Magic 125 Polish Pagan Pantheon 131 4 Slavic Pagan Beliefs The Slavic peoples are not a "race". Like the Romance and Germanic peoples, they are related by area and culture, not so much by blood. Today there are thirteen different Slavic groups divided into three blocs, Eastern, Southern and Western. These include the Russians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Serbians,Croatians, Macedonians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Kashubians, Albanians and Slovakians. Although the Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians are of Baltic tribes, we are including some of their customs as they are similar to those of their Slavic neighbors. Slavic Runes were called "Runitsa", "Cherty y Rezy" ("Strokes and Cuts") and later, "Vlesovitsa".