Crime, Punishment, and Colonization: a History of the Prison of Saint-Louis and the Development of the Penitentiary System in Senegal, Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Looters Vs. Traitors: the Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and Its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire

Looters vs. Traitors: The Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire Abstract: Since 2012, when broadcasting licenses were granted to various private television and radio stations in Mauritania, the controversy around the Battle of Um Tounsi (and Mauritania’s colonial past more generally) has grown substantially. One of the results of this unprecedented level of media freedom has been the prop- agation of views defending the Mauritanian resistance (muqawama in Arabic) to French colonization. On the one hand, verbal and written accounts have emerged which paint certain groups and actors as French colonial power sympathizers. At the same time, various online publications have responded by seriously questioning the very existence of a structured resistance to colonization. This article, drawing pre- dominantly on local sources, highlights the importance of this controversy in study- ing the western Saharan region social model and its contemporary uses. African Studies Review, Volume 63, Number 2 (June 2020), pp. 258– 280 Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba is Professor of History and Sociolinguistics at the University of Nouakchott, Mauritania (Ph.D. University of Provence (Aix- Marseille I); Fulbright Scholar resident at Northwestern University 2012–2013), and a Senior Research Consultant at the CAPSAHARA project (ERC-2016- StG-716467). E-mail: [email protected] Francisco Freire is an Anthropologist (Ph.D. Universidade Nova de Lisboa 2009) at CRIA–NOVA FCSH (Lisbon, Portugal). He is the Principal Investigator of the European Research Council funded project CAPSAHARA: Critical Approaches to Politics, Social Activism and Islamic Militancy in the Western Saharan Region (ERC-2016-StG-716467). -

Political Spontaneity and Senegalese New Social Movements, Y'en a Marre and M23: a Re-Reading of Frantz Fanon 'The Wretched of the Earth"

POLITICAL SPONTANEITY AND SENEGALESE NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, Y'EN A MARRE AND M23: A RE-READING OF FRANTZ FANON 'THE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH" Babacar Faye A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Dalton Anthony Jones © 2012 Babacar Faye All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor This project analyzes the social uprisings in Senegal following President Abdoulaye Wade's bid for a third term on power. From a perspectivist reading of Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth and the revolutionary strategies of the Algerian war of independence, the project engages in re-reading Fanon's text in close relation to Senegalese new social movements, Y'en A Marre and M23. The overall analysis addresses many questions related to Fanonian political thought. The first attempt of the project is to read Frantz Fanon's The Wretched from within The Cultural Studies. Theoretically, Fanon's "new humanism," as this project contends, can be located between transcendence and immanence, and somewhat intersects with the political potentialities of the 'multitude.' Second. I foreground the sociogeny of Senegalese social movements in neoliberal era of which President Wade's regime was but a local phase. Recalling Frantz Fanon's critique of the bourgeoisie and traditional intellectuals in newly postindependent African countries, I draw a historical continuity with the power structures in the postcolonial condition. Therefore, the main argument of this project deals with the critique of African political leaders, their relationship with hegemonic global forces in infringing upon the basic rights of the downtrodden. -

South-South De/Postcolonial Dialogues Reflections from Encounters Between a Decolonial Latin-American and Postcolonial Senegal

South-South de/postcolonial dialogues Reflections from encounters between a decolonial Latin-American and postcolonial Senegal Matías Pérez Ojeda del Arco Student number: 840701648020 Study Program: MSc. Development and Rural Innovation Course Number: SDC-80430 Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Supervisor: Dr. Pieter de Vries, SDC Group, WUR Examiner: Dr. Conny. Almekinders, KTI Group, WUR August 2017 “Decididamente, nos habían enseñado (pretenden seguir enseñándonos) el mundo de cabeza” Roberto Fernández-Retamar - Calibán [1971] (2016, p. 201). « Je n’ai jamais eu la prétention de faire école, j’ai eu la prétention d’être moi-même, d’abord, et d’être sûr que je suis moi-même » Amadou Hampâté Bá - Sur les traces d’Amkoullel l’enfant Peul (1998). i Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................ iii Preface ................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. vi Table of figures ....................................................................................................................vii CHAPTER I: THE NEED FOR SOUTH-SOUTH DE/POSTCOLONIAL DIALOGUES ............................ 1 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Ransoming, Collateral, and Protective Captivity on the Upper Guinea Coast Before 1650: Colonial Continuities, Contemporary Echoes1

MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY WORKING PAPERS WORKING PAPER NO. 193 PETER MARK RANSOMING, COLLATERAL, AND PROTECTIVE CAPTIVITY ON THE UppER GUINEA COAST BEFORE 1650: COLONIAL CONTINUITIES, Halle / Saale 2018 CONTEMPORARY ISSN 1615-4568 ECHOES Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, PO Box 110351, 06017 Halle / Saale, Phone: +49 (0)345 2927- 0, Fax: +49 (0)345 2927- 402, http://www.eth.mpg.de, e-mail: [email protected] Ransoming, Collateral, and Protective Captivity on the Upper Guinea Coast before 1650: colonial continuities, contemporary echoes1 Peter Mark2 Abstract This paper investigates the origins of pawning in European-African interaction along the Upper Guinea Coast. Pawning in this context refers to the holding of human beings as security for debt or to ensure that treaty obligations be fulfilled. While pawning was an indigenous practice in Upper Guinea, it is proposed here that when the Portuguese arrived in West Africa, they were already familiar with systems of ransoming, especially of members of the nobility. The adoption of pawning and the associated practice of not enslaving members of social elites may be explained by the fact that these customs were already familiar to both the Portuguese and their West African hosts. Vestiges of these social institutions may be found well into the colonial period on the Upper Guinea Coast. 1 The author expresses his gratitude to Jacqueline Knörr and to the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology for the opportunity to carry out the research and writing of this paper. Thanks are also due to the members of the Research Group “Integration and Conflict along the Upper Guinea Coast (West Africa)”, to Marek Mikuš for his comments on an earlier draft, and to Alex Dupuy of Wesleyan University for his insightful comments. -

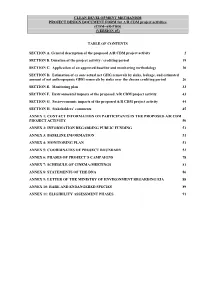

Cdm-Ar-Pdd) (Version 05)

CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM for A/R CDM project activities (CDM-AR-PDD) (VERSION 05) TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 2 SECTION B. Duration of the project activity / crediting period 19 SECTION C. Application of an approved baseline and monitoring methodology 20 SECTION D. Estimation of ex ante actual net GHG removals by sinks, leakage, and estimated amount of net anthropogenic GHG removals by sinks over the chosen crediting period 26 SECTION E. Monitoring plan 33 SECTION F. Environmental impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 43 SECTION G. Socio-economic impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 44 SECTION H. Stakeholders’ comments 45 ANNEX 1: CONTACT INFORMATION ON PARTICIPANTS IN THE PROPOSED A/R CDM PROJECT ACTIVITY 50 ANNEX 2: INFORMATION REGARDING PUBLIC FUNDING 51 ANNEX 3: BASELINE INFORMATION 51 ANNEX 4: MONITORING PLAN 51 ANNEX 5: COORDINATES OF PROJECT BOUNDARY 52 ANNEX 6: PHASES OF PROJECT´S CAMPAIGNS 78 ANNEX 7: SCHEDULE OF CINEMA-MEETINGS 81 ANNEX 8: STATEMENTS OF THE DNA 86 ANNEX 9: LETTER OF THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT REGARDING EIA 88 ANNEX 10: RARE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES 89 ANNEX 11: ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT PHASES 91 SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity A.1. Title of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> Title: Oceanium mangrove restoration project Version of the document: 01 Date of the document: November 10 2010. A.2. Description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> The proposed A/R CDM project activity plans to establish 1700 ha of mangrove plantations on currently degraded wetlands in the Sine Saloum and Casamance deltas, Senegal. -

The Slow Death of Slavery in Nineteenth Century Senegal and the Gold Coast

That Most Perfidious Institution: The slow death of slavery in nineteenth century Senegal and the Gold Coast Trevor Russell Getz Submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School or Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10673252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673252 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract That Most Perfidious Institution is a study of Africans - slaves and slave owners - and their central roles in both the expansion of slavery in the early nineteenth century and attempts to reform servile relationships in the late nineteenth century. The pivotal place of Africans can be seen in the interaction between indigenous slave-owning elites (aristocrats and urban Euro-African merchants), local European administrators, and slaves themselves. My approach to this problematic is both chronologically and geographically comparative. The central comparison between Senegal and the Gold Coast contrasts the varying impact of colonial policies, integration into the trans-Atlantic economy; and, more importantly, the continuity of indigenous institutions and the transformative agency of indigenous actors. -

A Language of Learning Article

3/12/2020 Achieve3000: Lesson Printed by: Jessica Christian Printed on: March 12, 2020 A Language of Learning Article DAKAR, Senegal (Achieve3000, March 26, 2018). In sub-Saharan Africa, most children attend schools where lessons are not taught in their mother tongue. Instead, schools use a language that is more international, meaning that it's more commonly used worldwide. Some believe this system prepares kids for a successful future. Others say that teaching in an unfamiliar language can confuse children and affect learning. Senegal is an example of an African nation where students in second grade learn to read—not in their first language, but in French. French is Senegal's "colonial language." It became the official language when Senegal was a colony of France, between 1895 and 1960. (Many African Credit for photo and all related countries were once colonies of European nations, including France, the images: R. Shryock/VOA United Kingdom, and Portugal.) In Senegal, many people speak the At school, these students in Kaolack, language of their region or ethnic group at home instead of French. It's the Senegal, are taught in an same in other African nations. Many people speak local or ethnic international language (French) languages rather than the colonial language. rather than their local language. It's this familiarity with local languages that has many people calling for schools to reduce their use of colonial languages. Professor Mbacke Diagne of Dakar's Cheikh Anta Diop University studies language. He wants to integrate local languages into the standard teaching curriculum. Diagne cites Wolof, the nation's most widely spoken language. -

Le Ponton De Carabane Est En Service

Le ponton de Carabane est en service Extrait du Au Senegal http://au-senegal.com/le-ponton-de-carabane-est-en-service,6754.html Le ponton de Carabane est en service - Recherche - Actualités - Date de mise en ligne : samedi 6 juillet 2013 Au Senegal Copyright © Au Senegal Page 1/2 Le ponton de Carabane est en service Il a fallu près de deux ans pour réaliser le ponton de Carabane qui permet désormais aux navires d'accoster en toute sécurité et de désenclaver cette petite île située à l'embouchure du fleuve Casamance. Inauguration aujourd'hui 6 juillet. On nous l'avait promis depuis longtemps, c'est fait désormais : un ponton flambant neuf permet maintenant d'accoster de manière confortable à l'île de Carabane. Le ferry Dakar-Ziguinchor pourra désormais y faire escale, les pirogues pourront s'y amarrer et le commerce avec le continent pourra se développer. Carabane est à la fois une île et un village situés à l'extrême sud-ouest du Sénégal, dans l'embouchure du fleuve Casamance. Site touristique, c'est aussi du point de vue historique le premier comptoir colonial français en Casamance. On ne peut y accéder qu'en pirogue, une traversée de trente minutes depuis Elinkine. Le bateau le Joola qui assurait la liaison Dakar-Ziguinchor y faisait autrefois escale en s'ancrant au large, avec un transit jusqu'à l'île en pirogue. Cet arrêt fut supprimé après son naufrage, une des plus grandes catastrophes maritimes, laissant les habitants de Carabane bien isolés. Le chantier, attribué à Eiffage Sénégal, a permis de réaliser un appontement pour navires à passagers et un appontement à pirogues. -

The West Indian Mission to West Africa: the Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963

The West Indian Mission to West Africa: The Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963 by Bakary Gibba A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Bakary Gibba (2011) The West Indian Mission to West Africa: The Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963 Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Bakary Gibba Department of History, University of Toronto Abstract This thesis investigates the efforts of the West Indian Church to establish and run a fascinating Mission in an area of West Africa already influenced by Islam or traditional religion. It focuses mainly on the Pongas Mission’s efforts to spread the Gospel but also discusses its missionary hierarchy during the formative years in the Pongas Country between 1855 and 1863, and the period between 1863 and 1873, when efforts were made to consolidate the Mission under black control and supervision. Between 1873 and 1900 when additional Sierra Leonean assistants were hired, relations between them and African-descended West Indian missionaries, as well as between these missionaries and their Eurafrican host chiefs, deteriorated. More efforts were made to consolidate the Pongas Mission amidst greater financial difficulties and increased French influence and restrictive measures against it between 1860 and 1935. These followed an earlier prejudiced policy in the Mission that was strongly influenced by the hierarchical nature of nineteenth-century Barbadian society, which was abandoned only after successive deaths -

Creating Markets in Senegal

CREATING MARKETS SENEGAL IN CREATING A COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC SECTOR PRIVATE COUNTRY A A COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN SENEGAL Sustaining growth in an uncertain environment APRIL 2020 About IFC IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of the world. In fiscal year 2018, we delivered more than $23 billion in long-term financing for developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org © International Finance Corporation 2020. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 www.ifc.org The material in this report was prepared in consultation with government officials and the private sector in Senegal and is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The findings, interpretations, views, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent.