The Turkstream Pipeline in Light of the Security of Demand for Russian Gas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Southern Gas Corridor

Energy July 2013 THE SOUTHERN GAS CORRIDOR The recent decision of The State Oil Company of The EU Energy Security and Solidarity Action Plan the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) and its consortium identified the development of a Southern Gas partners to transport the Shah Deniz gas through Corridor to supply Europe with gas from Caspian Southern Europe via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) and Middle Eastern sources as one of the EU’s is a key milestone in the creation of the Southern “highest energy securities priorities”. Azerbaijan, Gas Corridor. Turkmenistan, Iraq and Mashreq countries (as well as in the longer term, when political conditions This Briefing examines the origins, aims and permit, Uzbekistan and Iran) were identified development of the Southern Gas Corridor, including as partners which the EU would work with to the competing proposals to deliver gas through it. secure commitments for the supply of gas and the construction of the pipelines necessary for its Background development. It was clear from the Action Plan that the EU wanted increased independence from In 2007, driven by political incidents in gas supplier Russia. The EU Commission President José Manuel and transit countries, and the dependence by some Barroso stated that the EU needs “a collective EU Member States on a single gas supplier, the approach to key infrastructure to diversify our European Council agreed a new EU energy and energy supply – pipelines in particular. Today eight environment policy. The policy established a political Member States are reliant on just one supplier for agenda to achieve the Community’s core energy 100% of their gas needs – this is a problem we must objectives of sustainability, competitiveness and address”. -

Nord Stream 2

Updated August 24, 2021 Russia’s Nord Stream 2 Natural Gas Pipeline to Germany Nord Stream 2, a natural gas pipeline nearing completion, is which accounted for about 48% of EU natural gas imports expected to increase the volume of Russia’s natural gas in 2020. Russian gas exports to the EU were up 18% year- export capacity directly to Germany, bypassing Ukraine, on-year in the first quarter of 2021. Factors behind reliance Poland, and other transit states (Figure 1). Successive U.S. on Russian supply include diminishing European gas Administrations and Congresses have opposed Nord Stream supplies, commitments to reduce coal use, Russian 2, reflecting concerns about European dependence on investments in European infrastructure, Russian export Russian energy and the threat of increased Russian prices, and the perception of many Europeans that Russia aggression in Ukraine. The German government is a key remains a reliable supplier. proponent of the pipeline, which it says will be a reliable Figure 1. Nord Stream Gas Pipeline System source of natural gas as Germany is ending nuclear energy production and reducing coal use. Despite the Biden Administration’s stated opposition to Nord Stream 2, the Administration appears to have shifted its focus away from working to prevent the pipeline’s completion to mitigating the potential negative impacts of an operational pipeline. Some critics of this approach, including some Members of Congress and the Ukrainian and Polish governments, sharply criticized a U.S.-German joint statement on energy security, issued on July 21, 2021, which they perceived as indirectly affirming the pipeline’s completion. -

Statoil-2015-Statutory-Report.Pdf

2015 Statutory report in accordance with Norwegian authority requirements © Statoil 2016 STATOIL ASA BOX 8500 NO-4035 STAVANGER NORWAY TELEPHONE: +47 51 99 00 00 www.statoil.com Cover photo: Øyvind Hagen Statutory report 2015 Board of directors report ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 The Statoil share ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Our business ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Group profit and loss analysis .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Cash flows ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

W O R K I N G P a P E R Natural Gas Import and Export

W ORKING P APER Working Paper No26 July 2019 NATURAL GAS IMPORT AND EXPORT ROUTES IN SOUTH-EAST EUROPE AND TURKEY Gina Cohen Lecturer & Consultant on Natural Gas ΙΕΝΕ Working Paper No26 NATURAL GAS IMPORT AND EXPORT ROUTES IN SOUTH-EAST EUROPE AND TURKEY Author Gina Cohen, Lecturer & Consultant on Natural Gas Institute of Energy for SE Europe (IENE) 3, Alexandrou Soutsou, 106 71 Athens, Greece tel: 0030 210 3628457, 3640278 fax: 0030 210 3646144 web: www.iene.gr, e-mail: [email protected] Copyright ©2019, Institute of Energy for SE Europe All rights reserved. No part of this study may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the Institute of Energy for South East Europe. Please note that this publication is subject to specific restrictions that limit its use and distribution. [2] ACRONYMS AERS - Energy Agency of the Republic of Serbia AIIB - Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank BCM - Billion cubic meters BOTAS - Boru Hatlari Ile Petroleum Tasima Anonim Sirketi (Petroleum Pipeline Corporation) BRUA - Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria BRUSKA- Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Slovakia-Austria EBRD - European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EITI - Exctractive Industries Transparency Initiative EPDK - Enerji Piyasasi Duzenleme Kurumu (Energy Market Regulatory Authority) EU - European Union FGSZ - Foldgazszallito Zrt. (Hungarian Gas Transmission System Operator) FSRU – Floating Storage and Regasification unit GWh - Gigawatt hour HAG - Hungaria-Austria-Gasleitung (Hungary-Austria Interconnector) -

South Stream Becomes Serbian Stream

Serbia: South Stream becomes Serbian stream The position of the Republic of Serbia as a candidate for EU membership on the one hand and cooperation with Russia on the other allows this country to position itself as an intermediary between the two sides, between the East and the West. The re-export of Russian gas to other countries is exactly such an opportunity. While Russia is under EU sanctions and while the official Union policy reduces dependence on Russian gas (despite obvious contradictions like North Stream 2), Russia cannot sell gas to the EU under free market conditions. Serbia, as a still non-member of the Union, does not oblige to follow the same rules. The specific position in which Serbia is located allows this country to use it for its economic progress. After the Kremlin summit at the end of December last year, there were rumors that Russia will begin to change Russia’s natural gas supply agreement to Serbia, and allow this country to sell Russian gas to other countries, and now we are closer to realizing that plan. The Russian newsletter announced that Moscow will put an end to the agreement that stipulates that Russian natural gas can only be sold on the Serbian market. The agreement covers the period from 2012 to 2021 and envisages the delivery of up to five billion cubic meters per year. In order for this to be possible, Serbia will have to build new pipelines. At present, its pipes are connected only to Bosnia and Herzegovina, but since December, construction of a special branch of the gas pipeline from Dimitrovgrad to Niš has begun. -

THE WARP of the SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-Westernism, Russophilia, Traditionalism

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA studies17 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism... BELGRADE, 2016 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism… Edition: Studies No. 17 Publisher: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia www.helsinki.org.rs For the publisher: Sonja Biserko Reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Dubravka Stojanović Prof. Dr. Momir Samardžić Dr Hrvoje Klasić Layout and design: Ivan Hrašovec Printed by: Grafiprof, Belgrade Circulation: 200 ISBN 978-86-7208-203-6 This publication is a part of the project “Serbian Identity in the 21st Century” implemented with the assistance from the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. CONTENTS Publisher’s Note . 5 TRANSITION AND IDENTITIES JOVAN KOMŠIĆ Democratic Transition And Identities . 11 LATINKA PEROVIĆ Serbian-Russian Historical Analogies . 57 MILAN SUBOTIĆ, A Different Russia: From Serbia’s Perspective . 83 SRĐAN BARIŠIĆ The Role of the Serbian and Russian Orthodox Churches in Shaping Governmental Policies . 105 RUSSIA’S SOFT POWER DR. JELICA KURJAK “Soft Power” in the Service of Foreign Policy Strategy of the Russian Federation . 129 DR MILIVOJ BEŠLIN A “New” History For A New Identity . 139 SONJA BISERKO, SEŠKA STANOJLOVIĆ Russia’s Soft Power Expands . 157 SERBIA, EU, EAST DR BORIS VARGA Belgrade And Kiev Between Brussels And Moscow . 169 DIMITRIJE BOAROV More Politics Than Business . 215 PETAR POPOVIĆ Serbian-Russian Joint Military Exercise . 235 SONJA BISERKO Russia and NATO: A Test of Strength over Montenegro . -

The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU-Turkey Relations

September 2017 FEUTURE Online Paper No. 5 The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU-Turkey Relations Nona Mikhelidze, IAI Nicolò Sartori, IAI Oktay F. Tanrisever, METU Theodoros Tsakiris, ELIAMEP Online Paper No. 5 “The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU -Turkey Relations ” ABSTRACT The Turkey-Russia-EU energy triangle is a relationship of interdependence and strategic compromise. However, Russian support for secessionism and erosion of state autonomy in the Caucasus and Eurasia has proven difficult to reconcile for western European states despite their energy dependence. Yet, Turkey has enjoyed an enhanced bilateral relationship with Russia, augmenting its position and relevance in a strategic energy relationship with the EU. The relationship between Ankara and Moscow is principally based on energy security and domestic business interests, and has largely remained stable in times of regional turmoil. This paper analyses the dynamics of Ankara-Moscow cooperation in order to understand which of the three scenarios in EU –Turkey relations – conflict, cooperation or convergence – could be expected to develop bearing in mind that the partnership between Turkey and Russia has become unpredictable. The intimacy of Turkish-Russia energy relations and EU-Russian regional antagonism makes transactional cooperation on energy demand the most likely of future scenarios. A scenario in which both Brussels and Ankara will try to coordinate their relations with Russia through a positive agenda, in order to exploit the interdependence emerging within the “triangle”. ÖZET Türkiye Rusya ve AB arasındaki enerji üçgeni bir karşılıklı bağımlılık ve stratejik uzlaşma ilişkisidir. Ancak, her ne kadar Rusya’ya enerji bağımlılıkları olsa da, Batı Avrupalı devletler için Rusya’nın Kafkasya ve Avrasyadaki ayrılıkçılığa ve devlet özerkliğinin erozyonuna verdiği desteğin kabullenilmesinin zor olduğu ortaya çıkmıştır. -

Terrestrial Ecology

Chapter 11: Terrestrial Ecology URS-EIA-REP-204635 Table of Contents 11 Terrestrial Ecology ................................................................................... 11-1 11.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 11-1 11.2 Scoping ............................................................................................................ 11-1 11.2.1 ENVIID ................................................................................................ 11-2 11.2.2 Stakeholder Engagement ...................................................................... 11-2 11.2.3 Analysis of Alternatives ......................................................................... 11-4 11.3 Spatial and Temporal Boundaries ........................................................................ 11-4 11.3.1 Spatial Boundaries ................................................................................ 11-4 11.3.2 Temporal Boundaries .......................................................................... 11-11 11.4 Baseline Data .................................................................................................. 11-11 11.4.1 Introduction ....................................................................................... 11-11 11.4.2 Secondary Data .................................................................................. 11-11 11.4.3 Data Gaps .......................................................................................... 11-14 -

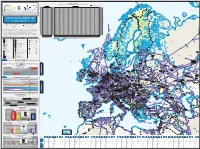

System Development Map 2019 / 2020 Presents Existing Infrastructure & Capacity from the Perspective of the Year 2020

7125/1-1 7124/3-1 SNØHVIT ASKELADD ALBATROSS 7122/6-1 7125/4-1 ALBATROSS S ASKELADD W GOLIAT 7128/4-1 Novaya Import & Transmission Capacity Zemlya 17 December 2020 (GWh/d) ALKE JAN MAYEN (Values submitted by TSO from Transparency Platform-the lowest value between the values submitted by cross border TSOs) Key DEg market area GASPOOL Den market area Net Connect Germany Barents Sea Import Capacities Cross-Border Capacities Hammerfest AZ DZ LNG LY NO RU TR AT BE BG CH CZ DEg DEn DK EE ES FI FR GR HR HU IE IT LT LU LV MD MK NL PL PT RO RS RU SE SI SK SM TR UA UK AT 0 AT 350 194 1.570 2.114 AT KILDIN N BE 477 488 965 BE 131 189 270 1.437 652 2.679 BE BG 577 577 BG 65 806 21 892 BG CH 0 CH 349 258 444 1.051 CH Pechora Sea CZ 0 CZ 2.306 400 2.706 CZ MURMAN DEg 511 2.973 3.484 DEg 129 335 34 330 932 1.760 DEg DEn 729 729 DEn 390 268 164 896 593 4 1.116 3.431 DEn MURMANSK DK 0 DK 101 23 124 DK GULYAYEV N PESCHANO-OZER EE 27 27 EE 10 168 10 EE PIRAZLOM Kolguyev POMOR ES 732 1.911 2.642 ES 165 80 245 ES Island Murmansk FI 220 220 FI 40 - FI FR 809 590 1.399 FR 850 100 609 224 1.783 FR GR 350 205 49 604 GR 118 118 GR BELUZEY HR 77 77 HR 77 54 131 HR Pomoriy SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT MAP HU 517 517 HU 153 49 50 129 517 381 HU Strait IE 0 IE 385 385 IE Kanin Peninsula IT 1.138 601 420 2.159 IT 1.150 640 291 22 2.103 IT TO TO LT 122 325 447 LT 65 65 LT 2019 / 2020 LU 0 LU 49 24 73 LU Kola Peninsula LV 63 63 LV 68 68 LV MD 0 MD 16 16 MD AASTA HANSTEEN Kandalaksha Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 MK 0 MK 20 20 MK 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM NL 418 963 1.381 NL 393 348 245 168 1.154 NL T +32 2 894 51 00 T +32 2 209 05 00 PL 158 1.336 1.494 PL 28 234 262 PL Twitter @ENTSOG Twitter @GIEBrussels PT 200 200 PT 144 144 PT [email protected] [email protected] RO 1.114 RO 148 77 RO www.entsog.eu www.gie.eu 1.114 225 RS 0 RS 174 142 316 RS The System Development Map 2019 / 2020 presents existing infrastructure & capacity from the perspective of the year 2020. -

Prospectus of 31 March 2014

Statoil ASA, prospectus of 31 March 2014 Registration Document Prospectus Statoil ASA Registration Document Stavanger, 31 March 2014 Dealer: 1 of 47 Statoil ASA, prospectus of 31 March 2014 Registration Document Important information The Registration Document is based on sources such as annual reports and publicly available information and forward looking information based on current expectations, estimates and projections about global economic conditions, the economic conditions of the regions and industries that are major markets for the Company's and Guarantor’s (including subsidiaries and affiliates) lines of business. A prospective investor should consider carefully the factors set forth in chapter 1 Risk factors, and elsewhere in the Prospectus, and should consult his or her own expert advisers as to the suitability of an investment in the bonds. This Registration Document is subject to the general business terms of the Dealer, available at its website (www.dnb.no). The Dealer and/or affiliated companies and/or officers, directors and employees may be a market maker or hold a position in any instrument or related instrument discussed in this Registration Document, and may perform or seek to perform financial advisory or banking services related to such instruments. The Dealer’s corporate finance department may act as manager or co-manager for this Company and/or Guarantor in private and/or public placement and/or resale not publicly available or commonly known. Copies of this presentation are not being mailed or otherwise distributed or sent in or into or made available in the United States. Persons receiving this document (including custodians, nominees and trustees) must not distribute or send such documents or any related documents in or into the United States. -

Annual Report 2015

REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA ENERGY REGULATOR AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT Power Sector Situation and ERE Activity during 2015 Tirana, 2016 Annual Report 2015 March 2016 ERE CONTENT I. Introductory Speech ........................................................................................................................ 9 Petrit Ahmeti......................................................................................................................................... 14 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 15 ERE Organizational Structure... .......................................................................................................... 15 ERE Board … ........................................................................................................................................ 15 ERE Organisation chart ...................................................................................................................... 17 1. Part I: Electricity Market Regulation ……………………....................................................................... 18 1.1 Electricity Market ………............................................................................................................. 19 1.2 Electricity Generation ……… ..................................................................................................... 22 1.2.1 Electricity Capacities and Generation …………… ................................................................... -

Download Publication

JULY 2021 A Phantom Menace: Is Russian LNG a Threat to Russia’s Pipeline Gas in Europe? OIES PAPER: NG 171 Dr Vitaly Yermakov & Dr Jack Sharples, OIES The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2021 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-182-2 JULY 2021: A Phantom Menace: Is Russian LNG a Threat to Russia’s Pipeline Gas in Europe? ii Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Context: Russia on an international gas market transformed by LNG ............................................... 2 2. Russia adjusts its gas strategy to reflect growing LNG ambitions ...................................................... 4 3. From strategy to policy: the Russian regulatory context and the right of non-Gazprom companies to export LNG .............................................................................................................................................. 6 4. Key