Little League Rule Myths.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt. Airy Baseball Rules Majors: Ages 11-12

______________ ______________ “The idea of community . the idea of coming together. We’re still not good at that in this country. We talk about it a lot. Some politicians call it “family”. At moments of crisis we are magnificent in it. At those moments we understand community, helping one another. In baseball, you do that all the time. You can’t win it alone. You can be the best pitcher in baseball, but somebody has to get you a run to win the game. It is a community activity. You need all nine players helping one another. I love the bunt play, the idea of sacrifice. Even the word is good. Giving your self up for the whole. That’s Jeremiah. You find your own good in the good of the whole. You find your own fulfillment in the success of the community. Baseball teaches us that.” --Mario Cuomo 90% of this game is half mental. --- Yogi Berra Table of Contents A message from the “Comish” ……………………………………… 1 Mission Statement ……………………………………………………… 2 Coaching Goals ……………………………………………………… 3 Basic First Aid ……………………………………………………… 5 T-Ball League ……………………………………………………… 7 Essential Skills Rules Schedule AA League ………………………………………………………. 13 Essential Skills Rules Schedule AAA League ………………………………………………………… 21 Essential Skills Rules Schedule Major League …………………………………………………………. 36 Essential Skills Rules Schedule Playoffs Rules and Schedule…………………………………………….. 53 Practice Organization Tips ..…………………………… ………………….. 55 Photo Schedule ………………………………………………………………….. 65 Welcome to Mt. Airy Baseball Mt. Airy Baseball is a great organization. It has been providing play and instruction to boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 17 for more than thirty years. In that time, the league has grown from twenty players on two teams to more than 600 players in five age divisions, playing on 45 teams. -

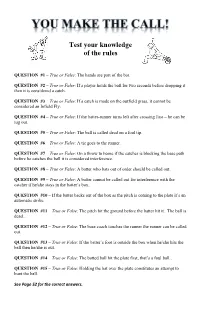

Test Your Knowledge of the Rules

Test your knowledge of the rules QUESTION #1 – True or False: The hands are part of the bat. QUESTION #2 – True or False: If a player holds the ball for two seconds before dropping it then it is considered a catch. QUESTION #3 – True or False: If a catch is made on the outfield grass, it cannot be considered an Infield Fly. QUESTION #4 – True or False: If the batter-runner turns left after crossing first – he can be tug out. QUESTION #5 – True or False: The ball is called dead on a foul tip. QUESTION #6 – True or False: A tie goes to the runner. QUESTION #7 – True or False: On a throw to home if the catcher is blocking the base path before he catches the ball it is considered interference. QUESTION #8 – True or False: A batter who bats out of order should be called out. QUESTION #9 – True or False: A batter cannot be called out for interference with the catcher if he/she stays in the batter’s box. QUESTION #10 – If the batter backs out of the box as the pitch is coming to the plate it’s an automatic strike. QUESTION #11 – True or False: The pitch hit the ground before the batter hit it. The ball is dead.. QUESTION #12 – True or False: The base coach touches the runner the runner can be called out. QUESTION #13 – True or False: If the batter’s foot is outside the box when he/she hits the ball then he/she is out. QUESTION #14 – True or False: The batted ball hit the plate first, that’s a foul ball. -

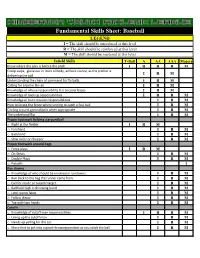

Fundamental Skills Sheet: Baseball

Fundamental Skills Sheet: Baseball LEGEND I = The skill should be introduced at this level R = The skill should be reinforced at this level M = The skill should be mastered at this level Infield Skills T-Ball A AA AAA Majors Know where the play is before the pitch I R R R M Creep steps, glove out in front of body, athletic stance, as the pitcher is I R M delivering the ball Understanding the chain of command for fly balls I R M Calling for a ball in the air I R M Knowledge of whose responsibility it is to cover bases I R M Knowledge of back up responsibilities I R R M Knowledge of bunt rotation responsibilities I R M How to locate the fence when running to catch a foul ball I R M Circling around ground balls when appropriate I R M The underhand flip I R M Proper footwork fielding a groundball o Right at the fielder I R M o Forehand I R M o Backhand I R M o Slow roller or chopper I R M Proper footwork around bags o Force plays I R M o On Steals I R M o Double Plays I R M o Pickoffs I Run downs o Knowledge of who should be involved in rundowns I R M o Run back to the bag the runner came from I R M o Call for inside or outside target I R M o Ball held high in throwing hand I R M o Limit pump fakes I R M o Follow throw I R M o Tag with two hands I R M Cutoffs o Knowledge of cutoff man responsibilities I R R M o Lining up the cutoff man I R M o Hands up yelling for the cut I R M o Move feet to get into a good throwing position as you catch the ball I R M Outfield Skills T-Ball A AA AAA Majors Know where the play is before the pitch I R R R -

2 – 3 Wall Ball Only a Jelly Ball May Be Used for This Game. 1. No Games

One Fly Up Switch 5. After one bounce, receiving player hits the ball 1 – 2 – 3 Wall Ball Use a soccer ball only. Played in Four Square court. underhand to any another square. No “claws” (one hand Only a jelly ball may be used for this game. 1. The kicker drop kicks the ball. on top and one hand on the bottom of the ball). 2. Whoever catches the ball is the next kicker. 1. Five players play at a time, one in each corner and one 6. Players may use 1 or 2 hands, as long as it is underhand. 1. No games allowed that aim the ball at a student standing 3. Kicker gets 4 kicks and if the ball is not caught, s/he in the middle of the court. 7. Players may step out of bounds to play a ball that has against the wall. picks the next kicker. bounced in their square, but s/he may not go into 2. No more than three players in a court at one time. 2. When the middle person shouts “Switch!” in his/her another player’s square. 3. First person to court is server and number 1. No “first loudest voice, each person moves to a new corner. Knock Out 8. When one player is out, the next child in line enters at serves”. 3. The person without a corner is out and goes to the end Use 2 basketballs only for this game. the D square, and the others rotate. 4. Ball may be hit with fist, open palm, or interlocked of the line. -

Common Baseball Rule Myths

Common Baseball Rule Myths Rob Winter CRLL Chief Umpire Many misunderstandings on the field are the result of “Everybody Knows That...” rules myths. Listed below are a collection of common misbeliefs about Little League baseball and softball rules. Each of these statements are FALSE. If you have any questions, please contact CRLL's Chief Umpire at [email protected] Myth #1 A pitch that bounces to the plate cannot be hit. A pitch is a ball delivered to the batter by the pitcher. It doesn't matter how it gets to the batter. The batter may hit any pitch that is thrown. Rule: 2.00 PITCH. (If the ball does not cross the foul line, it is not a pitch.) Myth #2 The batter does not get first base if hit by a pitch after it bounces. A pitch is a ball delivered to the batter by the pitcher. It doesn't matter how it gets to the batter. If the batter is hit by a pitch while attempting to avoid it, he is awarded first base. Rules: 2.00 PITCH, 6.08(b). Myth #3 The hands are considered part of the bat. The hands are part of a person's body. If a pitch hits the batter's hands the ball is dead; if he swung at the pitch, a strike is called (NOT a foul). If he was avoiding the pitch, he is awarded first base. Rules: 2.00 PERSON, TOUCH, STRIKE (e) and 6.05(f) Official Baseball Rules. Myth #4 If the batter breaks his wrists when swinging, its a strike. -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

FTRL 2017 Major League Rules

FTRL 2017 Major League Rules FTRL believes in teaching the youth of our community fundamental skills, sportsmanship and teamwork, while also providing friendly competition and enjoyment. It is not intended as a staging center for adult egos. General League Rules 1. Major league games consist of six innings per game. Each team receives three outs per inning. 1.1. The decision to cancel games due to inclement weather; will be solely the decision of the league President. 1.1.1. In the event the President is unavailable to render a decision on game impacted by the weather, then the Vice-President will be charged with that duty, followed by the Head of Grounds, and finally the Player Agent. 1.2. In the event that lightning is present 20 minutes prior to or during games, then all games will be cancelled immediately. Any game not completed will be rescheduled for another night. 1.3. All games that have begun and been delayed more than 20 minutes due to weather, will be cancelled and if not completed, and will be rescheduled for another night. 1.4. A game will be considered complete if three (3) full innings have been played, even if tied. 1.5. If the game goes over three (3) innings and then is cancelled, the score as of the last full inning completed will be official, even if tied. 1.6. There will be a 2-hour time limit on all games, except during playoffs. During the playoffs, the game will continue until the 6 inning completion or the mercy rule has been reached. -

S1) Do Not Pitch (S2) Foul Ball, Time Out, Dead Ball (S3

Approved OHSAA Baseball Signal Chart Play (S1) Description: Pointing with right hand toward the pitcher and say “Play.” Ball is now live. Do Not Pitch (S2) Description: Hold right hand in front of our body with palm facing out. Ball is dead and must be put back in play (S13). Foul ball, Time Out, Dead Ball (S3) Description: Both hands open above the head. Ball is dead immediately. 1 Strike (S4) Description: Stand straight up, bring your right hand up in front of your body, make a fist and say “strike” Foul Tip (S5) Description: Stand upright and pass right hand over the left hand signifying foul tip. Ball is still live. Count (S6) Description: Left hand is balls, right hand strikes. Hold both hand up in front of your body slightly above the shoulders. Signal should be forward towards pitcher and verbalized loud enough for Catcher, Batter & Pitcher. 2 Safe/Uncaught 3rd Strike (S7) Description: Start with your arms extended directly in front of your body and swing them open at shoulder height. Appeal on Check Swing ( 8 ) Description: Step out from behind the catcher, extend your left arm, palm up and ask the base umpire “Did He Go?” Safe /Did Not Go(S9) Description: Start with your arms extended directly in front of your body and swing them open at shoulder height. Used to signal that batter did not go when plate umpire asks “Did he go”. 3 Out (S10) Description: Bring your right arm up, make a 90 degree angle, make a fist and with hammering action call, “He’s out” Infield Fly (S11) Description: Once the ball has reached its Apex and you determine it is an infield fly, point your right hand toward ball and say “Infield Fly, batter is out”. -

Top 40 Baseball Rule Myths

Top 40 Baseball Rule Myths All of the following statements are FALSE. Read the explanations and rule references to find out why. Top 40 Baseball Rule Myths 1. The hands are considered part of the bat. 2. The batter-runner must turn to his right after over-running first base. 3. If the batter breaks his wrists when swinging, it's a strike. 4. If a batted ball hits the plate first it's a foul ball. 5. The batter cannot be called out for interference if he is in the batter's box. 6. The ball is dead on a foul-tip. 7. The batter may not switch batter's boxes after two strikes. 8. The batter who batted out of order is the person declared out. 9. The batter may not overrun first base when he gets a base-on-balls. 10. (N/A: J,S,B League Only)The batter is out if he starts for the dugout before going to first after a dropped third strike. 11. If the batter does not pull the bat out of the strike zone while in the bunting position, it's an automatic strike. 12. The batter is out if a bunted ball hits the ground and bounces up and hits the bat while batter is holding the bat. 13. The batter is out if his foot touches the plate. 14. The batter-runner is always out if he runs outside the running lane after a bunted ball. 15. A runner is out if he slaps hands or high-fives other players, after a homerun is hit over the fence. -

OFFICIAL RULES of SOFTBALL (Copyright by the International Softball Federation Playing Rules Committee)

OFFICIAL RULES OF SOFTBALL (Copyright by the International Softball Federation Playing Rules Committee) New Rules and/or changes are bolded and italicized in each section. References to (SP ONLY) include Co-ed Slow Pitch. Wherever “FAST PITCH ONLY (FP ONLY)” appears in the Official Rules, the same rules apply to Modified Pitch with the exception of the pitching rule. "Any reprinting of THE OFFICIAL RULES without the expressed written consent of the International Softball Federation is strictly prohibited." Wherever "he'' or "him" or their related pronouns may appear in this rule book either as words RULE 1 or as parts of words, they have been used for literary purposes and are meant in their generic sense (i.e. To include all humankind, or both male and female sexes). RULE 1. DEFINITIONS. – Sec. 1. ALTERED BAT. Sec. 1/DEFINITIONS/Altered Bat A bat is altered when the physical structure of a legal bat has been changed. Examples of altering a bat are: replacing the handle of a metal bat with a wooden or other type handle, inserting material inside the bat, applying excessive tape (more than two layers) to the bat grip, or painting a bat at the top or bottom for other than identification purposes. Replacing the grip with another legal grip is not considered altering the bat. A "flare" or "cone" grip attached to the bat is considered an altered bat. Engraved “ID” marking on the knob end only of a metal bat is not considered an altered bat. Engraved “ID” marking on the barrel end of a metal bat is considered an altered bat. -

Little League Baseball & Softball Beginner Umpire Training

Little League Baseball & Softball Beginner Umpire Training Patrick O’Rourke, Umpire in chief, Redmond West [email protected] George Cannon, Umpire in chief, Kirkland National [email protected] Steven Kehrli, Umpire in chief, Kirkland National [email protected] Agenda Actions: • 1. Provide your name, email, mobile, League, Division / team Pre-game • e.g., Joe West, [email protected], 425-123-4567, • Safe and out RWLL BB Coast / Braves • • Appeals E.g., Jill East, [email protected], 206-123-4567, KNLL SB AAA / Vision • Obstruction / interference 2. Complete background check by March 11 • Fair ball, foul ball 3. See welcome email from Arbiter and log-in; edit your profile 4. Sign-up to umpire games • Strike and ball 5. Get a hat for your league (RWLL, KALL or KNLL) • Time • Arbiter system • Appendix: 58-71 Version Feb. 27 “It’s about kids and character development using baseball as a tool” Terms • Batter • Batter-Runner (BR) • Runner (R1, R2, R3) • Fielder (F1-F9) • Protest, Appeal, (Gripe) Websites for learning http://www.littleleagueumpiring101.com/ http://umpirebible.com/rules.htm http://www.littleleagueu.org/quiz/2016/06/02/LLU+Umpire+Quiz+101 Youtube: search “little league umpire” 3 Pregame: Gear Home Plate (HP) Umpire Base Umpire • *^ Hat • *^ Ball bag (black, grey) • *^ Hat • *^ Shirt (same • *^ Plate brush • *^ Shirt (same color as HP) color as bases) • *^ Chest protector • Grey slacks • *^ Mask • *^ Shin guards • Black belt • Grey slacks • Cup • *Indicator (optional) • Black belt • Plate shoes (optional) • Water • *^ Indicator • Small pencil • Cleats/Turf shoes • Water • Lineup holder • *^ Red flag (baseball only) (optional) • Plate gear in the car! * RWLL provided ^ KNLL provided 4 Pregame: Partner • Check the rainout line • Hartman Park: Call (425) 200-0076 (Mon-Fri 3:01pm; Sat-Sun 8:01am). -

LL Rule Book

NSBF LITTLE LEAGUE RULES 2018 NBLL Rule Book NBLL Rule Book Rev 2.9 NSBF LITTLE LEAGUE RULES 2018 Table of Contents 1 BATTING, OUTS, AND STRIKES 1 OUTS 1 STRIKES AND FOULS 1 THE STRIKE ZONE 2 BALLS AND WALKS 2 2 RUNNING THE BASES 2 OVER-RUNNING THE BASES 2 TAGGING RUNNERS OUT 2 FORCE(D)-OUT VS. TAG(GED)-OUT SITUATIONS 3 RULE CONCERNING RUNS SCORED WHEN 3RD OUT IS MADE 3 3 RULES CONCERNING POP FLY BALLS 3 4 STEALING BASES 4 HEADFIRST SLIDES ARE PROHIBITED!! 4 5 GAME RULES: 4 NUMBER OF PLAYERS. 4 THE “INFIELD FLY RULE” DOES APPLY. 4 NO LEAD-OFFS ARE ALLOWED. 4 BALKS 4 OVERTHROWN TO THE PITCHER 4 THE UMPIRE’S JUDGMENT 4 THE DROPPED 3RD STRIKE RULE DOES NOT APPLY. 4 6 PITCHING RULES: 5 PITCHERS WILL PITCH FROM 12 METERS. 5 FACE MASK 5 EACH PITCHER WILL BE ALLOWED 75 PITCHES PER DAY MAXIMUM. 5 PITCH COUNT REACHED. 5 WHEN A PITCHER IS REPLACED IN A GAME 5 NUMBER OF TRIPS TO THE MOUND. 5 HITTING BATTERS 5 1-INNING BREAK 5 7 HITTING RULES: 6 BATTING ORDER 6 NBLL Rule Book Rev 2.9 NSBF LITTLE LEAGUE RULES 2018 MODIFIED HITTING RULES. 6 BUNTING 6 BAT SIZE 6 8 AWARDING BASES 7 ONE-BASE AWARDS 7 TWO-BASE AWARDS 8 9 GENERAL: 9 10 DEFINITION OF TERMS 12 GLOSSARY 12 DEFINITION OF TERMS 13 11 ADDENDUM 17 NBLL Rule Book Rev 2.9 NSBF LITTLE LEAGUE RULES 2018 Basic Little League Baseball Rules For young players and parents unfamiliar with the rules of baseball, here are the basic rules: 1 Batting, Outs, and Strikes A youth baseball game usually consists of 6 innings.