APPENDIX TABLE of APPENDICES Appendix a Opinion, United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Senne V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Lacrosse Timer/Scoring Directions

Rev. Feb 2011 Women’s Lacrosse Timer/Scoring Directions Pre-Game Activities • Table personnel should remain neutral and not cheer for any team or players on the field. • Home team is responsible for scorers table, official time clock(s), and official score sheet (officials must sign at end of game). • Introduce yourself to officials before the game. • Provide your team roster (reflecting active players for that game) to the visiting team 10 minutes prior to start time. • Sideline personnel, excepting photographers, must have a active US Lacrosse number. Game time • Consists of Two 25-minute halves. • Game is “Running Time”, do not stop the timer during normal stoppages of game play. • Stop timer when whistle blows to signal a goal. • Stop timer when whistle blows to signal an injury. • Stop timer when whistle blows and the official signals a time out (crossed arms over the head). • Stop the clock on every whistle for last 2 minutes of each half • Start timer when whistle blows to start play. End of period • Come onto the field by the sideline for the last 30 seconds of play in the half/game by the closest trailing official. • Both Halves: Notify nearest official verbally when there are 30 seconds left, then count down loudly from 10, sounding horn at zero. Halftime • Ten minutes. • Notify officials verbally when there are 30 seconds left. Signaling of penalties • Official signals the team that fouled. • Official says and signals the foul committed. • A Yellow Card held up indicates a major foul. Record player # and time of penalty and allowed return time on the score sheet. -

Girls Lacrosse Modifications 2021

NEW JERSEY STATE INTERSCHOLASTIC ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION Robbinsville, NJ 08691 TO: LACROSSE COACHES, ATHLETIC DIRECTORS AND OFFICIALS FROM: Kim DeGraw-Cole, Assistant Director DATE: February 2021 RE: The 2020 NFHS Girls Lacrosse Rules shall govern all NJSIAA Girls Lacrosse games. *COVID Considerations & Modifications will be a separate document. State Rules Interpreter: Maureen Dzwill [email protected] 609-472-9103 Girls’ Lacrosse Coaches, Athletic Directors and Officials are especially advised to read all rules carefully and to note the following modifications: NJSIAA Specific Sport Regulations-Girls Lacrosse-Section 9 (pages 86-87) page 87: DURATION OF PLAY A player shall play in no more than three (3) halves during the same calendar day. This would include freshman, sophomore, junior varsity and varsity competition. PLEASE NOTE: In case of overtime play, as provided in Rule 4, each period of overtime is considered an extension of the second half and substitution may be made. TIE-BREAKER FOR REGULAR SEASON AND TOURNAMENT PLAY: (Rule 4, Section 6) To ensure accurate power points, ties must be broken during regular season play by using the tie-breaking procedure listed below. This procedure will also be used during the State Tournament. 1. When the score is tied at the end of regular playing time, both teams will have a five (5) minute rest and toss a coin for choice of ends. (The alternate possession shall continue from regulation) 2. The game will be started with a center draw. The winner will be decided by “sudden victory”. The team scoring the first goal wins the game. 3. Each overtime period will be no more than six minutes in length of stop-clock time (clock stops on every whistle). -

Version 3.4 OFFICIAL RULE BOOK

NATIONAL FLAG FOOTBALL RULES Version 3.4 OFFICIAL RULE BOOK 1 NATIONAL FLAG FOOTBALL RULES Version 3.4 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 PLAYING TIME 3 DIVISIONS 3 FORMAT 3 PLAYER ATTIRE 3 EQUIPMENT 3 COACHES 3 POSSESSIONS 4 ONE WAY FIELD SET UP 4 TWO WAY FIELD SET UP 5 GENERAL OFFENSE 5 PASSING GAME 6 RECEIVING GAME 6 RUNNING GAME 6 GENERAL DEFENSE 6 FLAG PULLING 6 INTERCEPTIONS 7 NO RUN ZONES 7 RUSHING OF THE QUARTERBACK 7 REPLAY OF DOWN 7 DEAD BALLS 8 SCORING 8 EXTRA POINTS 8 SAFETIES 9 TIME SITUATIONS 8 OVERTIME 8 FORFEITS 9 PROTEST RULE 9 GENERAL PENALTY INFORMATION 9 WARNINGS 9 OFFENSIVE PENALTIES 9 DEFENSIVE PENALTIES 10 EJECTIONS 10 SPORTSMANSHIP 10 2 NATIONAL FLAG FOOTBALL RULES Version 3.4 PLAYING TIME All children should receive equal playing time for both offense and defense in each game they participate in. Coaches are asked to monitor each other and report any infractions that they see. If a coach is caught not evenly rotating his/her players, disciplinary action will be taken. DIVISIONS Players are placed on teams using a variety of methods including but not limited to school and grade. Teams are placed into divisions based on grade level. Divisions may be separate or combined depending on the number of children registered. Divisions are as follows: o Lombardi Division (Usually 1st grade and younger) o Shula Division (Usually 2nd and/or 3rd grade) o Madden Division (Usually 4th grade and older) FORMAT The game is played with five (5) players. However, a minimum of four (4) players must be on the field at all times. -

Tournament Overtime Procedures

Overtime Game Procedures The following overtime procedure as been approved by the OHSAA to be used at all Sectional, District, Regional and State tournament games. Please review these procedures, KEEP THEM HANDY AT YOUR SITE, and review with officials the correct procedures prior to the start of the game. It is essential the correct overtime procedures be followed, knowing schools have not utilized overtime procedures at any time during the regular season. Also, please tear out and remove the Special Announcement and give to your Public Address Announcer to be read prior to the beginning of the overtime period. When the score is tied at the end of regulation time, the referee will instruct both teams to return to their respective team benches. There will be five minutes during which both teams may confer with their coaches and the head referee will instruct both teams as to proper procedures. A. Teams will play one 15-minute sudden victory overtime period. If neither team scores during the first overtime period, teams will play a second 15-minute sudden victory overtime period. 1. Prior to the first overtime period, a coin toss shall be held as in Rule 5-2-2(d) (3). 2. If neither team scores during the first 15-minute overtime period, teams shall change ends for the second overtime period. 3. There shall be a two-minute interval between periods. B. If neither team scores during the overtimes, all coaches, officials and team captains following a two minute interval shall assemble at the halfway line to review the procedures for a penalty kick shootout as outlined below: 1. -

GAME NOTES Tuesday, May 11, 2021

GAME NOTES Tuesday, May 11, 2021 2019 PCL Pacific Southern Division Champions Game 6 – Home Game 6 Sacramento River Cats (2-3) (AAA-S.F. Giants) vs. Las Vegas Reyes de Plata (3-2) (AAA-Oakland Athletics) Aviators At A Glance . The Series (L.V. leads 3-2) Overall Record: 3-2 (.600) Home: 3-2 (.600) PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Road: 0-0 (.000) Day Games: 1-0 (1.000) SACRAMENTO LAS VEGAS Tues. (7:05) – LHP Anthony Banda (1-0, 0.00) RHP Matt Milburn 0-0, 0.00) Night Games: 2-2 (.500) Wednesday, May 12 OFF DAY Follow the Aviators on Facebook/Las Vegas Aviators Baseball Team & Twitter/@AviatorsLV Probable Starting Pitchers (Las Vegas at Reno, May 13-18) RENO LAS VEGAS Thurs. (6:35) – TBA RHP Parker Dunshee (0-1, 13.50) Radio: KRLV AM 920 - Russ Langer Fri. (6:35) – TBA RHP Grant Holmes (0-0, 15.00) Web & TV: www.aviatorslv.com; MiLB.TV Sat. (4:05) – TBA RHP Paul Blackburn (0-0. 5.40) Aviators vs. River Cats: The Las Vegas Reyes de Plata professional baseball team, Triple-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics, will host the Sacramento River Cats, Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants, tonight in the finale of the season -opening six-game series in Triple-A West action at Las Vegas Ballpark (8,834)…Las Vegas is 3-2 on the homestand…following an off day on Wednesday, May 12, Las Vegas will embark on its first road trip of the season to Northern Nevada to face intrastate rival, the Reno Aces, Triple-A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks, in a six-game series at Greater Nevada Field from Thursday-Tuesday, May 13-18. -

Seattle Area Baseball Umpire Camp

Seattle Area Baseball Umpire Camp February 8th, 2020 - 8:00am-4:00pm Everett Memorial Stadium • A one-day camp featuring current Major League, Minor League, and college umpires. • Tailored for umpires of all levels. • Includes indoor instruction, cage training, and field training. • Provides training credit for local area associations. Little League High School Sub-Varsity High School Varsity Apprentice B Tier Connie Mack C Tier A Tier High School C-Games Tournament Tier Introduction Introduction Introduction 8:00am-8:30am Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Center Center Center Orientation to Umpiring Everett Stadium Cages Field Training Everett Stadium 8:30am-10-30am Field Training Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Cages Everett Stadium Center Taking the Next Step 10:30am-12:30pm 12:30pm-1:30pm LUNCH at Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Cages Field Training Mistakes even the best make Everett StadiumCenter Everett Stadium Conference Center 1:30pm-3:30pm Finale Finale Finale 3:30pm-4:00pm Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Center Center Center NOTES: • Umpire support: • Tripp Gibson – Major League Umpire • Mike Muchlinski – Major League Umpire • Brian Hertzog – NCAA Div I & Div II Umpire • Jacob Metz – Minor League Umpire • Cage Training and Field Training support from College–level umpires from NBUA and SCBUA • Uniform: wear the uniform for the bases/field. Plate gear will be worn over the field uniform when in the cages. • Lunch will be provided: sub-sandwiches, chips, water, soda • Cost: $15.00 (assessed at the end of the 2020 season) This covers the cost of the trainers and the food. -

Development, Evolution, and Bargaining in the National Football League

DEVELOPMENT, EVOLUTION, AND BARGAINING IN THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE Thomas Sisco The National Football League [hereinafter: NFL] is the most popular professional sports organization in the United States, but even with the current popularity and status of the NFL, ratings and the public perception of the on-field product have been on steady decline.1 Many believe this is a byproduct of the NFL being the only one of the 4 major professional sports leagues in the country without a self-controlled system for player development. Major League Baseball [hereinafter: MLB] has a prominent and successful minor league baseball system, the National Hockey League has the American Hockey League and East Coast Hockey League, the National Basketball Association [hereinafter: NBA] has the 22 team development league widely known as “The D- League”, but the NFL relies on the National Collegiate Athletic Association [hereinafter: NCAA] to develop young players for a career in their league. The Canadian Football League and the Arena Football League are generally inadequate in developing players for the NFL as the rules of gameplay and the field dimensions differ from those of NFL football.2 NFL Europe, a developmental league founded by Paul Tagliabue, former NFL Commissioner, has seen minor success.3 NFL Europe, existing by various names during its lifespan, operated from 1991 until it was disbanded in 2007.4 During its existence, the NFL Europe served as a suitable incubator for a 1 Darren Rovell, NFL most popular for 30th year in row, ESPN (January 26, 2014), http://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/10354114/harris-poll-nfl-most-popular-mlb-2nd, . -

Baseball Stadium Market Feasibility Study for Franklin, Wisconsin

Franklin Baseball Stadium Market Feasibility Study SUBMITTED TO Zimmerman Ventures SUBMITTED BY C.H. Johnson Consulting, Incorporated March 20, 2014 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I TRANSMITTAL LETTER SECTION II INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION III ECONOMIC AND DEMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS 6 SECTION IV COMPARATIVE MARKET ANALYSIS & DEMAND PROJECTIONS 20 SECTION V FRONTIER LEAGUE STADIUM AND MINOR LEAGUE CASE STUDIES 42 SECTION VI ECONOMIC AND FISCAL IMPACTS ANALYSIS 69 SECTION VII STADIUM FUNDING OPTIONS 83 APPENDIX I 6 East Monroe Street | Fifth Floor | Chicago, Illinois 60603 | Phone: 312.447.2010 | Fax: 312.444.1125 www.chjc.com | [email protected] SECTION I TRANSMITTAL LETTER 6 East Monroe Street | Fifth Floor | Chicago, Illinois 60603 | Phone: 312.447.2010 | Fax: 312.444.1125 www.chjc.com | [email protected] March 20, 2014 Mr. Michael Zimmerman President Zimmerman Ventures 4600 Loomis Road, Suite 310 Milwaukee, WI 53220 Re: Feasibility Study for a Proposed Minor League Baseball Stadium Dear Mr. Zimmerman: Johnson Consulting is pleased to submit this DRAFT report to Zimmerman Ventures (“Client”) that analyzes the market and financial feasibility of a proposed minor league baseball stadium in Franklin, WI. This report also quantifies the total economic and fiscal impact the proposed stadium will have on the local community. Johnson Consulting has no responsibility to update this report for events and circumstances occurring after the date of this report. The findings presented herein reflect analyses of primary and secondary sources of information. Johnson Consulting used sources deemed to be reliable, but cannot guarantee their accuracy. Moreover, some of the estimates and analyses presented in this study are based on trends and assumptions, which can result in differences between the projected results and the actual results. -

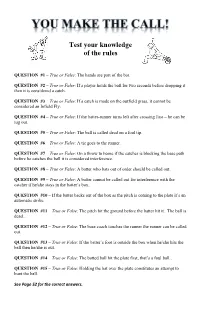

Test Your Knowledge of the Rules

Test your knowledge of the rules QUESTION #1 – True or False: The hands are part of the bat. QUESTION #2 – True or False: If a player holds the ball for two seconds before dropping it then it is considered a catch. QUESTION #3 – True or False: If a catch is made on the outfield grass, it cannot be considered an Infield Fly. QUESTION #4 – True or False: If the batter-runner turns left after crossing first – he can be tug out. QUESTION #5 – True or False: The ball is called dead on a foul tip. QUESTION #6 – True or False: A tie goes to the runner. QUESTION #7 – True or False: On a throw to home if the catcher is blocking the base path before he catches the ball it is considered interference. QUESTION #8 – True or False: A batter who bats out of order should be called out. QUESTION #9 – True or False: A batter cannot be called out for interference with the catcher if he/she stays in the batter’s box. QUESTION #10 – If the batter backs out of the box as the pitch is coming to the plate it’s an automatic strike. QUESTION #11 – True or False: The pitch hit the ground before the batter hit it. The ball is dead.. QUESTION #12 – True or False: The base coach touches the runner the runner can be called out. QUESTION #13 – True or False: If the batter’s foot is outside the box when he/she hits the ball then he/she is out. QUESTION #14 – True or False: The batted ball hit the plate first, that’s a foul ball. -

Little League Rule Myths.Pdf

Many misunderstandings on the field are the result of “Everybody Knows That…” rules myths. Listed below are a collection of common misbeliefs about Little League baseball and softball rules. Each of these statements are false. Clicking on each link will explain the correct ruling. 1. The ball is dead on a foul tip. Reality: The ball is NOT dead on a foul tip. Rule 2.00 FOUL TIP explicitly says that a foul tip is a live ball. Much of the confusion surrounding this probably comes from a misunderstanding of what a foul tip actually is: A FOUL TIP is a batted ball that goes sharp and direct from the bat to the catcher’s hands and is legally caught. It is not a foul tip unless caught and any foul tip that is caught is a strike, and the ball is in play. It is not a catch if it is a rebound, unless the ball has first touched the catcher’s glove or hand. A foul tip can only be caught by the catcher. Thus, it is only a foul tip if the catcher catches the ball. A ball that hits the bat and goes straight back to the backstop is a foul ball not a foul tip. 2. A batted ball that hits the plate is a foul ball. Reality: For the purposes of a fair/foul determination, home plate is no different from the ground. As it happens, all of home plate is in fair territory, so if a batted ball touches it, it has merely struck part of fair territory. -

2 – 3 Wall Ball Only a Jelly Ball May Be Used for This Game. 1. No Games

One Fly Up Switch 5. After one bounce, receiving player hits the ball 1 – 2 – 3 Wall Ball Use a soccer ball only. Played in Four Square court. underhand to any another square. No “claws” (one hand Only a jelly ball may be used for this game. 1. The kicker drop kicks the ball. on top and one hand on the bottom of the ball). 2. Whoever catches the ball is the next kicker. 1. Five players play at a time, one in each corner and one 6. Players may use 1 or 2 hands, as long as it is underhand. 1. No games allowed that aim the ball at a student standing 3. Kicker gets 4 kicks and if the ball is not caught, s/he in the middle of the court. 7. Players may step out of bounds to play a ball that has against the wall. picks the next kicker. bounced in their square, but s/he may not go into 2. No more than three players in a court at one time. 2. When the middle person shouts “Switch!” in his/her another player’s square. 3. First person to court is server and number 1. No “first loudest voice, each person moves to a new corner. Knock Out 8. When one player is out, the next child in line enters at serves”. 3. The person without a corner is out and goes to the end Use 2 basketballs only for this game. the D square, and the others rotate. 4. Ball may be hit with fist, open palm, or interlocked of the line. -

The Necessity of Major League Baseball's Antitrust Exemption

PROTECTING AMERICA’S PASTIME: THE NECESSITY OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL’S ANTITRUST EXEMPTION FOR THE SURVIVAL OF MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL BRADLEY V. MURPHY* INTRODUCTION “How can you not be romantic about baseball?”1 Imagine a warm summer evening in Rome, Georgia. This city of just under 36,000 residents2 is home to the Rome Braves, the Class-A affiliate of the Atlanta Braves.3 State Mutual Stadium is filled to capacity as the local residents pack the stands to cheer on their hometown Braves.4 The smell of peanuts, popcorn, and hotdogs emanates throughout the stadium. A beer vendor climbs up and down the stadium steps hollering, “Ice cold beer!” Between innings, children are brought out on the field to partake in on-field promotions. After the game, these same children line up to run the bases, meet the mascot, and enjoy the postgame firework display. This minor league game brings the people of Rome, Georgia together and provides them with a common identity. Bradley Reynolds, general manager of the Double-A Mobile BayBears, highlighted the importance of minor league baseball when he said, “What keeps fans coming back isn’t baseball. If they want a better baseball game, they can see it on ESPN. This is about affordability, family fun, wholesome entertainment. That’s what makes this business unique and what makes it work.”5 Considered to be “America’s National Pastime,”6 baseball holds a special place in the hearts of many. In “Field of Dreams,” arguably the most famous baseball movie of all- time, Terence Mann, an author played by James Earl Jones, discussed the importance of baseball to many Americans: * J.D.