Urban Development Alternatives for the San Ysidro/Tijuana Port of Entry Border Zone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from San Diego's Border Wall

RESEARCH REPORT (CBP Photo/Mani Albrecht) LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL The limits to using walls for migration, drug trafficking challenges By Adam Isacson and Maureen Meyer December 2017 " The border doesn’t need a wall. It needs better-equipped ports of entry, investi- gative capacity, technology, and far more ability to deal with humanitarian flows. In its current form, the 2018 Homeland Security Appropriations bill is pursuing a wrong and wasteful approach. The ex- perience of San Diego makes that clear." LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL December 2017 | 2 SUMMARY The prototypes for President Trump's proposed border wall are currently sitting just outside San Diego, California, an area that serves as a perfect example of how limited walls, fences, and barriers can be when dealing with migration and drug trafficking challenges. As designated by stomsCu and Border Protection, the San Diego sector covers 60 miles of the westernmost U.S.-Mexico border, and 46 of them are already fenced off. Here, fence-building has revealed a new set of border challenges that a wall can’t fix. The San Diego sector shows that: • Fences or walls can reduce migration in urban areas, but make no difference in rural areas. In densely populated border areas, border-crossers can quickly mix in to the population. But nearly all densely populated sections of the U.S.-Mexico border have long since been walled off. In rural areas, where crossers must travel miles of terrain, having to climb a wall first is not much of a deterrent. A wall would be a waste of scarce budget resources. -

Opportunities for Regional Collaboration on the Border: Sharing the European Border Experience with the San Diego/Tijuana Region

Opportunities for Regional Collaboration on the Border: Sharing the European border experience with the San Diego/Tijuana region Dr. Freerk Boedeltje, Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias, San Diego State University, May 2012 How to read this white paper? This white paper highlights best practices and barriers for local cross border cooperation across the European Union and will suggest policy options relevant to the San Diego-Tijuana region. The research done in Europe has been carried out as part of two large scheme EU wide projects sponsored under the 5th and 6th framework Programme of European Commission. Code named EXLINA and EUDIMENSIONS, the research consisted of a consortium of multiple universities across the European Union and took 8 years between 2002 and 2009. Both project have sought to understand the actual and potential role of cross border co-operation beyond the external borders of the EU and focused on specific local development issues, including economic development, cultural and educational matters, urban development, local democracy and environmental issues. The research was designed to address practical aspects of cross-border co- operation across and beyond the external borders of the European Union. The case studies that covered most part of the external borders of the EU centred on how changes within Europe’s political space are being interpreted and used by actors with a stake in bi-national/cross-border cooperation. This whitepaper compares and contrast the San Diego-Tijuana realities with cross border cooperation in border regions of the European Union. In addition to improving our understanding how local border regions function within a global context, the whitepaper highlight best practices and barriers for local cross border cooperation and will suggest policy options relevant to the San Diego Region and the Tijuana Tecate and Playas de Rosarito Metropolitan Zone. -

Vier Portillo

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 444444444444444444444444U JAVIER PORTILLO, Petitioner, - v - UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. 4444444444444444444444444U PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT 4444444444444444444444444U ELIZABETH A. MISSAKIAN P.O. Box 601879 San Diego, CA 92160 (619) 233-6534 Counsel for Petitioner JAVIER PORTILLO LIST OF PARTIES [X All parties appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. [] All parties do not appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. - prefix - QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW Whether the Ninth Circuit’s analysis of the facts was inadequate and whether, when the entirety of facts presented at trial was considered, there was sufficient evidence that petitioner Javier Portillo had knowledge of narcotics hidden in his vehicle at the time he crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. - prefix - TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.. iii OPINION BELOW. 1 JURISDICTION. 2 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS. 2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE . 2 STATEMENT OF FACTS. 3 Government’s Case-in-Chief. 3 Defense Case. 8 Testimony of Javier Portillo. 9 REASON TO GRANT THE WRIT. 11 THERE WAS INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE FOR THE JURY TO CONCLUDE THAT JAVIER PORTILLO KNEW OF THE PRESENCE OF NARCOTICS WITHIN HIS VEHICLE WHEN HE CROSSED INTO THE UNITED STATES AT THE SAN YSIDRO PORT OF ENTRY.. 12 A. The Claim is Preserved.. 12 B. Standard of Review . 12 C. Evidence at Trial Was Insufficient to Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that Javier Portillo Knew There Were Narcotics in his Vehicle. -

Gateway Parking

GATEWAY PARKING STABILIZED INCOME INVESTMENT OFFERING MEMORANDUM INVESTMENT ADVISORS CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT JOSEPH LISING The information contained in the following offering memorandum is proprietary Managing Director and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it Irvine Office from Cushman & Wakefield and it should not be made available to any other person +1 949 372 4896 Direct or entity without the written consent of Cushman & Wakefield. By taking possession +1 949 474 0405 Fax [email protected] of and reviewing the information contained herein the recipient agrees to hold and Lic. 01248258 treat all such information in the strictest confidence. The recipient further agrees that recipient will not photocopy or duplicate any part of the offering memorandum. If you have no interest in the subject property now, please return this offering memorandum to Cushman & Wakefield. This offering memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified financial and physical information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Cushman & Wakefield has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCBs or asbestos, the compliance with local, state and federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

Periférico Aeropuerto-Zapata-Doble Piso a Playas”

PRIMERA ETAPA DE LA VIALIDAD “PERIFÉRICO AEROPUERTO-ZAPATA-DOBLE PISO A PLAYAS” MEMORIA TÉCNICA Memoria Técnica Página 1 de 134 INDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................... 6 2. CARACTERIZACIÓN DEL TERRITORIO ........................................................... 8 2.1. Localización ........................................................................................................ 8 2.2. Extensión ............................................................................................................ 8 2.3. Orografía ............................................................................................................. 9 2.4. Hidrografía ........................................................................................................ 10 2.5. Marco Geológico Regional ............................................................................... 10 2.5.1. Ambiente tectónico ............................................................................................. 10 2.5.2. Litología regional ................................................................................................. 11 2.6. Principales infraestructuras viales .................................................................... 12 3. ESTADO ACTUAL DE LA VÍA DE LA JUVENTUD ORIENTE ...................... 15 4. PROYECTO GEOMÉTRICO DE LA AUTOPISTA ............................................. 19 4.1. Objetivo ........................................................................................................... -

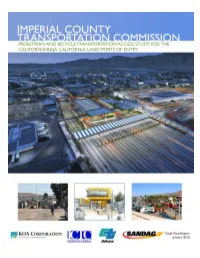

2.1 Description of Border Function

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................2 1.2 COMMUNITY AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT .........................................................................................................4 1.3 EXISTING CONDITIONS ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT ......................................................................................4 1.4 PROGRAMMED IMPROVEMENTS AND FUTURE CONDITIONS .............................................................................5 1.5 ORIGIN AND DESTINATION SURVEY RESULTS ..................................................................................................5 1.6 RECOMMENDED PROJECTS .................................................................................................................................5 1.7 FUNDING STRATEGY AND VISION .....................................................................................................................7 2.0 INTRODUCTION 8 2.1 DESCRIPTION OF BORDER FUNCTION ...............................................................................................................9 2.2 DEMOGRAPHIC DATA ...................................................................................................................................... 12 2.3 CROSSING AND WAIT TIME SUMMARIES ......................................................................................................... 14 2.4 ENVIRONMENTAL, HEALTH, -

2013 San Diego

BINATIONAL HAZARDOUS MATERIALS PREVENTION AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN AMONG THE COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA AND THE CITY OF TIJUANA, BAJA CALIFORNIA January 14, 2013 Binational Hazardous Materials Prevention and Emergency Response Plan Among the County Of San Diego, the City of San Diego, California, and the City of Tijuana, Baja California January 14, 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2005-Present ...................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2003 .................................................................................................... 6 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................... 10 PARTICIPATING AGENCIES................................................................................................... 17 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 23 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 23 1.0 TIJUANA/SAN DIEGO BORDER REGION ................................................................. 25 1.1 General Aspects of the Region ........................................................................................ 25 1.1.1 Historical and Cultural Background ................................................................ 25 1.1.2 Geographic Location -

California-Baja California Border Master Plan

California-Baja California Border Master Plan Plan Maestro Fronterizo California-Baja California Final Report Informe Final SEPTEMBER 2008 SEPTIEMBRE 2008 SEPTEMBER 2008 SEPTIEMBRE 2008 California-Baja California Border Master Plan Plan Maestro Fronterizo California-Baja California Final Report Informe Final Submitted to Caltrans, District 11 4050 Taylor Street San Diego, CA 92110 Submitted by SANDAG Service Bureau 401 B Street, Suite 800 San Diego, CA 92101-4231 Phone 619.699.1900 Fax 619.699.1905 www.sandag.org/servicebureau The California-Baja California Border Master Plan was commissioned by the U.S./Mexico Joint Working Committee to the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and the Secretariat of Infrastructure and Urban Development of Baja California (Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano del Estado de Baja California or SIDUE) for the California-Baja California border region. El Plan Maestro Fronterizo California-Baja California fue comisionado por el Comité Conjunto de Trabajo de los Estados Unidos y México a Caltrans y a SIDUE para la región fronteriza de California-Baja California. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... ES-1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... ES-1 Study Purpose and Objectives ........................................................................................................ -

Otay Mesa – Mesa De Otay Transportation Binational Corridor

Otay Mesa – Mesa de Otay Transportation Binational Corridor Early Action Plan Housing September 2006 Economic Development Environment TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Foundation of the Otay Mesa-Mesa de Otay Binational Corridor Strategic Plan..................................1 The Collaboration Process...........................................................................................................................1 The Strategic Planning Process and Early Actions .....................................................................................3 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................3 ISSUES FOR EVALUATION AND WORK PROGRAMS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................5 The Binational Study Area ..........................................................................................................................5 Issues Identified ...........................................................................................................................................5 Interactive Polling........................................................................................................................................7 Process.......................................................................................................................................................7 Results .......................................................................................................................................................8 -

FINAL San Ysidro Port of Entry Reconfiguration Mobility Study

FINAL San Ysidro Port of Entry Reconfiguration Mobility Study Prepared for: Prepared by: January 2010 San Ysidro Port of Entry Reconfiguration Mobility Study FINAL Concept Plan Report Table of Contents 1.0 STUDY PURPOSE..................................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 EXISTING SETTING ................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 Border Area Transportation Facilities and Services ............................................................................................ 7 2.1.2 Border Crossings .............................................................................................................................................13 2.1.3 Area Traffic Analysis ........................................................................................................................................15 2.1.4 Existing Conflicts and Deficiencies....................................................................................................................20 2.2 PROJECTED 2030 SETTING ......................................................................................................................................29 2.2.1 General Services Administration (GSA) -

Gateway Parking

GATEWAY PARKING STABILIZED INCOME INVESTMENT OFFERING MEMORANDUM INVESTMENT ADVISORS CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT JOSEPH LISING The information contained in the following offering memorandum is proprietary Managing Director and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it Irvine Office from Cushman & Wakefield and it should not be made available to any other person +1 949 372 4896 Direct or entity without the written consent of Cushman & Wakefield. By taking possession +1 949 474 0405 Fax [email protected] of and reviewing the information contained herein the recipient agrees to hold and Lic. 01248258 treat all such information in the strictest confidence. The recipient further agrees that recipient will not photocopy or duplicate any part of the offering memorandum. If you have no interest in the subject property now, please return this offering memorandum to Cushman & Wakefield. This offering memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified financial and physical information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Cushman & Wakefield has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCBs or asbestos, the compliance with local, state and federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

On the Borderline: Abuses at the United States - Mexico Border

ON THE BORDERLINE: ABUSES AT THE UNITED STATES - MEXICO BORDER US-Mexico Border Program American Friends Service Committee San Diego Area Office 3850 Westgate Pl. Bld.100| San Diego, CA 92105 t. 619-233-4114 f. 619-233-6247 [email protected] http://afsc.org/office/san-diego-ca © 2017 American Friends Service Committee The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker organization that includes people of various faiths who are committed to social justice, peace, and humanitarian service. Our work is based on the principles of the Religious Society of Friends, the belief in the worth of every person, and faith in the power of love to overcome violence and injustice. AFSC was founded in 1917 by Quakers to provide conscientious objectors an opportunity to aid civilian war victims. AFSC’s San Diego office, the US-Mexico Border Program, was established in 1977 and focuses on uplifting the rights and dignity of border residents, migrants, and refugees in the region. About the Authors Sofia Sotres is the Human Rights Program Associate for the American Friends Service Committee’s US- Mexico Border Program in San Diego, California. She has worked with AFSC since 2016, focusing on documenting border abuse cases. Sotres has a Bachelor’s degree in Law from the Autonomous University of Baja California. Pedro Rios is the Program Director for the American Friends Service Committee’s US-Mexico Border Program in San Diego, California. He has worked at AFSC since 2003, focusing on border and immigration issues. Rios has a Bachelor’s degree in English from the University of San Diego and a Master’s degree in Ethnic Studies from the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University.