Opportunities for Regional Collaboration on the Border: Sharing the European Border Experience with the San Diego/Tijuana Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from San Diego's Border Wall

RESEARCH REPORT (CBP Photo/Mani Albrecht) LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL The limits to using walls for migration, drug trafficking challenges By Adam Isacson and Maureen Meyer December 2017 " The border doesn’t need a wall. It needs better-equipped ports of entry, investi- gative capacity, technology, and far more ability to deal with humanitarian flows. In its current form, the 2018 Homeland Security Appropriations bill is pursuing a wrong and wasteful approach. The ex- perience of San Diego makes that clear." LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL December 2017 | 2 SUMMARY The prototypes for President Trump's proposed border wall are currently sitting just outside San Diego, California, an area that serves as a perfect example of how limited walls, fences, and barriers can be when dealing with migration and drug trafficking challenges. As designated by stomsCu and Border Protection, the San Diego sector covers 60 miles of the westernmost U.S.-Mexico border, and 46 of them are already fenced off. Here, fence-building has revealed a new set of border challenges that a wall can’t fix. The San Diego sector shows that: • Fences or walls can reduce migration in urban areas, but make no difference in rural areas. In densely populated border areas, border-crossers can quickly mix in to the population. But nearly all densely populated sections of the U.S.-Mexico border have long since been walled off. In rural areas, where crossers must travel miles of terrain, having to climb a wall first is not much of a deterrent. A wall would be a waste of scarce budget resources. -

Vier Portillo

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 444444444444444444444444U JAVIER PORTILLO, Petitioner, - v - UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. 4444444444444444444444444U PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT 4444444444444444444444444U ELIZABETH A. MISSAKIAN P.O. Box 601879 San Diego, CA 92160 (619) 233-6534 Counsel for Petitioner JAVIER PORTILLO LIST OF PARTIES [X All parties appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. [] All parties do not appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. - prefix - QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW Whether the Ninth Circuit’s analysis of the facts was inadequate and whether, when the entirety of facts presented at trial was considered, there was sufficient evidence that petitioner Javier Portillo had knowledge of narcotics hidden in his vehicle at the time he crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. - prefix - TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.. iii OPINION BELOW. 1 JURISDICTION. 2 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS. 2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE . 2 STATEMENT OF FACTS. 3 Government’s Case-in-Chief. 3 Defense Case. 8 Testimony of Javier Portillo. 9 REASON TO GRANT THE WRIT. 11 THERE WAS INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE FOR THE JURY TO CONCLUDE THAT JAVIER PORTILLO KNEW OF THE PRESENCE OF NARCOTICS WITHIN HIS VEHICLE WHEN HE CROSSED INTO THE UNITED STATES AT THE SAN YSIDRO PORT OF ENTRY.. 12 A. The Claim is Preserved.. 12 B. Standard of Review . 12 C. Evidence at Trial Was Insufficient to Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that Javier Portillo Knew There Were Narcotics in his Vehicle. -

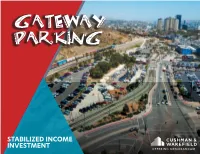

Gateway Parking

GATEWAY PARKING STABILIZED INCOME INVESTMENT OFFERING MEMORANDUM INVESTMENT ADVISORS CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT JOSEPH LISING The information contained in the following offering memorandum is proprietary Managing Director and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it Irvine Office from Cushman & Wakefield and it should not be made available to any other person +1 949 372 4896 Direct or entity without the written consent of Cushman & Wakefield. By taking possession +1 949 474 0405 Fax [email protected] of and reviewing the information contained herein the recipient agrees to hold and Lic. 01248258 treat all such information in the strictest confidence. The recipient further agrees that recipient will not photocopy or duplicate any part of the offering memorandum. If you have no interest in the subject property now, please return this offering memorandum to Cushman & Wakefield. This offering memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified financial and physical information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Cushman & Wakefield has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCBs or asbestos, the compliance with local, state and federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

2013 San Diego

BINATIONAL HAZARDOUS MATERIALS PREVENTION AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN AMONG THE COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA AND THE CITY OF TIJUANA, BAJA CALIFORNIA January 14, 2013 Binational Hazardous Materials Prevention and Emergency Response Plan Among the County Of San Diego, the City of San Diego, California, and the City of Tijuana, Baja California January 14, 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2005-Present ...................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2003 .................................................................................................... 6 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................... 10 PARTICIPATING AGENCIES................................................................................................... 17 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 23 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 23 1.0 TIJUANA/SAN DIEGO BORDER REGION ................................................................. 25 1.1 General Aspects of the Region ........................................................................................ 25 1.1.1 Historical and Cultural Background ................................................................ 25 1.1.2 Geographic Location -

FINAL San Ysidro Port of Entry Reconfiguration Mobility Study

FINAL San Ysidro Port of Entry Reconfiguration Mobility Study Prepared for: Prepared by: January 2010 San Ysidro Port of Entry Reconfiguration Mobility Study FINAL Concept Plan Report Table of Contents 1.0 STUDY PURPOSE..................................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 EXISTING SETTING ................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 Border Area Transportation Facilities and Services ............................................................................................ 7 2.1.2 Border Crossings .............................................................................................................................................13 2.1.3 Area Traffic Analysis ........................................................................................................................................15 2.1.4 Existing Conflicts and Deficiencies....................................................................................................................20 2.2 PROJECTED 2030 SETTING ......................................................................................................................................29 2.2.1 General Services Administration (GSA) -

Gateway Parking

GATEWAY PARKING STABILIZED INCOME INVESTMENT OFFERING MEMORANDUM INVESTMENT ADVISORS CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT JOSEPH LISING The information contained in the following offering memorandum is proprietary Managing Director and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it Irvine Office from Cushman & Wakefield and it should not be made available to any other person +1 949 372 4896 Direct or entity without the written consent of Cushman & Wakefield. By taking possession +1 949 474 0405 Fax [email protected] of and reviewing the information contained herein the recipient agrees to hold and Lic. 01248258 treat all such information in the strictest confidence. The recipient further agrees that recipient will not photocopy or duplicate any part of the offering memorandum. If you have no interest in the subject property now, please return this offering memorandum to Cushman & Wakefield. This offering memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified financial and physical information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Cushman & Wakefield has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCBs or asbestos, the compliance with local, state and federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

On the Borderline: Abuses at the United States - Mexico Border

ON THE BORDERLINE: ABUSES AT THE UNITED STATES - MEXICO BORDER US-Mexico Border Program American Friends Service Committee San Diego Area Office 3850 Westgate Pl. Bld.100| San Diego, CA 92105 t. 619-233-4114 f. 619-233-6247 [email protected] http://afsc.org/office/san-diego-ca © 2017 American Friends Service Committee The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker organization that includes people of various faiths who are committed to social justice, peace, and humanitarian service. Our work is based on the principles of the Religious Society of Friends, the belief in the worth of every person, and faith in the power of love to overcome violence and injustice. AFSC was founded in 1917 by Quakers to provide conscientious objectors an opportunity to aid civilian war victims. AFSC’s San Diego office, the US-Mexico Border Program, was established in 1977 and focuses on uplifting the rights and dignity of border residents, migrants, and refugees in the region. About the Authors Sofia Sotres is the Human Rights Program Associate for the American Friends Service Committee’s US- Mexico Border Program in San Diego, California. She has worked with AFSC since 2016, focusing on documenting border abuse cases. Sotres has a Bachelor’s degree in Law from the Autonomous University of Baja California. Pedro Rios is the Program Director for the American Friends Service Committee’s US-Mexico Border Program in San Diego, California. He has worked at AFSC since 2003, focusing on border and immigration issues. Rios has a Bachelor’s degree in English from the University of San Diego and a Master’s degree in Ethnic Studies from the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University. -

The International Gateway

THE INTERNATIONAL GATEWAY GOALS • Develop the border crossing as an International Gateway—a grand entrance into the United States, the City of San Diego, and the community of San Ysidro that serves as a center of cultural exchange and commerce serving both the tourist and the resident population. • Recognize and capitalize on the opportunities provided by the world’s busiest border crossing. Tap this outstanding economic opportunity and invest it back into the community. • Foster an active working relationship, a cultural exchange and an economic partnership with Mexico. • Develop an International Gateway that is sensitive to the security and safety issues associated with undocumented immigration and crime. • Reduce dependency on the Mexican consumer and provide incentives for tourists traveling to Tijuana to linger and purchase goods and services in San Ysidro. EXISTING CONDITIONS Tourism and the International Gateway The location of the International Gateway is generally along San Ysidro Boulevard, north of the San Ysidro Port of Entry, and south of I-805 and along Camino de la Plaza west of I-5. It is a major entrance into San Ysidro, San Diego, the United States and Mexico; however, traffic congestion, litter, overburdened sewers and storm drains, and visual clutter all detract from its potential. Visitors enter the area, buy gas and auto insurance, exchange money, and cross into Tijuana. Community residents seldom enter except to cross into Mexico. - 71 - The San Ysidro Port of Entry, at the hub of the International Gateway area, is reported to be the world’s busiest border crossing. According to United States Customs, it was crossed by approximately 53 million people in 1988—an average of 10 million northbound pedestrians and 12 million northbound vehicles. -

Final Rule; Technical and Land Transportation Are Listed in 8 Amendment

75631 Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol. 80, No. 232 Thursday, December 3, 2015 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER Department of Homeland Security facility, CBP will provide a variety of contains regulatory documents having general where CBP officers or employees are inspection services, including applicability and legal effect, most of which assigned to accept entries of immigration services. are keyed to and codified in the Code of merchandise, clear passengers, collect The CBX facility was designed in Federal Regulations, which is published under duties, and enforce the various accordance with U.S. and international 50 titles pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 1510. provisions of the customs and security standards. It includes an The Code of Federal Regulations is sold by immigration laws, as well as other laws enclosed pedestrian walkway the Superintendent of Documents. Prices of applicable at the border. The term ‘‘port connecting the Tijuana Airport in new books are listed in the first FEDERAL of entry’’ is used in the Code of Federal Mexico to San Diego, California and a REGISTER issue of each week. Regulations (CFR) in title 19 for customs passenger terminal located in San Diego purposes and in title 8 for immigration that will be used exclusively to process purposes. Subject to certain exceptions, ticketed Tijuana Airport passengers DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND all individuals entering the United traveling to and from the United States SECURITY States must present themselves to an via the walkway. The pedestrian immigration officer for inspection at a walkway will be accessible only for U.S. Customs and Border Protection U.S. -

Download PDF Arrow Forward

SMART BORDER COALITION™ San Diego-Tijuana MID-YEAR PROGRESS REPORT-2016 www.smartbordercoalition.com A Wall That Divides Us. A Goal to Unite Us. SMART BORDER COALITION Members of the Board 2016 Malin Burnham/Jose Larroque, Co-Chairs Jose Galicot Gaston Luken Eduardo Acosta Ted Gildred III Matt Newsome Raymundo Arnaiz Dave Hester JC Thomas Lorenzo Berho Russ Jones Mary Walshok Malin Burnham Mohammad Karbasi Steve Williams Frank Carrillo Pradeep Khosla Honorary Rafael Carrillo Pablo Koziner Jorge Astiazaran James Clark Jorge Kuri Marcela Celorio Salomon Cohen Elias Laniado Greg Cox Alberto Coppel Jose Larroque Kevin Faulconer Jose Fimbres Jeff Light William Ostick “OPPORTUNITY COMES FROM A SEAMLESS INTERNATIONAL REGION WHERE ALL CITIZENS WORK TOGETHER FOR MUTUAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL PROGRESS” MID-YEAR PROGRESS REPORT 2016 Secure and efficient border crossings are the primary goal of the Coalition. The Coalition works with existing stakeholders in both the public and private sectors to coordinate regional border efficiency efforts not duplicate them. Aquí Empiezan Las Patrias/The Countries Begin Here—Where the Border Meets the Pacific WHY THE BORDER MATTERS The United States is both Mexico’s largest export and largest import market. Hundreds of thousands or people cross the shared 2000-mile border daily During the time we spend on an SBC Board of Directors luncheon, the United States and Mexico will have traded more than $60 million worth of goods and services. The daily United States trade total with is Mexico is more than $1.5 billion supporting jobs in both countries. –courtesy of Consul General Will Ostick SAN DIEGO/TIJUANA BORDER ACCOMPLISHMENTS 1. -

Local Arrangement for Repatriation of Mexican Nationals

ATTACHMENT 1 Points of Contact 1. Notification of detention of Mexican nationals and Consular access. Consulate General of Mexico in San Diego, California San Ysidro Port of Entry (SYS POE) Consulate of Mexico in Calexico, California 2. Names, positions and contact information of the Officers responsible for receiving Mexican nationals and coordinating repatriation activities. National Institute of Migration (INM) Port of Entry El Chaparral /W-3 Mexicali, BC Port of Entry Mexicali 3. Names, positions and contact information of the Officers responsible for receiving information about the repatriation of persons suspected of committing, or known to have committed, criminal violations and have been identified as being of special interest to the Government of Mexico. Office of the Attorney General of Mexico (PGR) Attaché in San Diego, California Copy of the notification should be sent to: Consulate General of Mexico in San Diego, California Protection Department National Institute of Migration 4. Names, positions and contact information of the Officers responsible for delivering the Mexican nationals and coordinating repatriation activities. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Office of Field Operations (OFO) San Diego Field Office San Ysidro / Otay Port of Entry San Ysidro International Liaison Unit (ILU) San Ysidro / Otay Criminal Enforcement Unit (CEU) San Diego and Calexico Attachments to Local Arrangement for Repatriation of Mexican Nationals 2 Calexico Port of Entry (West) Calexico Port of Entry (East) Andrade Port of Entry Tecate Port of Entry U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) San Diego Sector Boulevard USBP Station Brown Field USBP Station Chula Vista USBP Station El Cajon USBP Station Imperial Beach USBP Station Murrieta USBP Station Campo USBP Station San Clemente USPB Station El Centro Sector Calexico USBP Station El Centro USBP Station Indio USBP Station U.S. -

Mexico Border Crossings at San Ysidro: Social and Environmental Effects for Pedestrian Crossers and San Diego Communities Study Information

U.S. – Mexico Border Crossings at San Ysidro: Social and Environmental Effects for Pedestrian Crossers and San Diego Communities Study Information Collaborators in The Healthy Borders San Ysidro Project: San Diego State University (SDSU) Graduate School of Public Health (GSPH) Casa Familiar San Diego Prevention Research Center (SDPRC) Funded by: •Health and Environmental Impacts of Border Crossing Delays and Traffic on Residents and Workers in the Community of San Ysidro and the San Diego Region’ grant (San Diego Foundation, PI Dr. PJE Quintana) •‘Pedestrian Border Element Project’ grant (California Endowment, PI David Flores) Outline: talk today 1.Environmental Effects of SY Border Crossings a. General Information b. Pedestrian study c. San Ysidro study d. Greenhouse gas study 2.Social Effects of SY Border Crossings 3.Conclusions and Solutions Environmental Effects Studies Objectives Pedestrian Study: Measure personal exposures to air toxics experienced by pedestrians San Ysidro Air Quality Study: Measure community air quality in the city of San Ysidro Greenhouse Gas Study: Estimate contribution of idling vehicle emissions to greenhouse gas emissions in the San Diego region Environmental Effects: Traffic-Related Emissions Noise Toxics NO 1-NP X Carbon Monoxide Particulate Matter (PM)(PM PM 2.5 , ‘ultrafine’ PM or PM 0.1 Greenhouse gas emissions Effects of Traffic-Related Air Pollution on Human Health In Adults… Traffic-related pollution linked to cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and cancer In Children… Links to asthma, reduced lung growth, bronchitis, leukemia, and birth defects Pedestrian Study Measure personal exposures to air pollutants experienced by pedestrians crossing border at San Ysidro POE 1. On people - 60 pedestrian border commuters who work or go to school in San Ysidro and live in Mexico and 40 controls San Ysidro only (one 24 hour period) - carry carbon monoxide and diesel pollutant monitors for 24 hours (including pedestrian commute across POE) - urine analyzed for diesel exposure 2.