Holocene Range Collapse of Giant Muntjacs and Pseudo- Endemism in the Annamite Large Mammal Fauna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Analysis of Human Overpopulation and Its Impact on Sustainability

Statistical Analysis of Human Overpopulation and its Impact on Sustainability Susanne Bradley Abstract In this project, I examine the relationship between population size and resource use, with particular emphasis on carbon emissions. I use a combination of time series methods and regression analysis to obtain forecasts for global carbon emissions and energy use to the year 2060, taking into account population growth and economic development. In general, my predictions are consistent with predictions already made by different experts, though mine tend to be slightly more pessimistic. I end by addressing some potential ways to decrease population growth rates. 1 Introduction In the twentieth century, human population nearly quadrupled from 1.6 billion to 6.1 billion. Over that same period of time, global carbon consumption increased by a factor of twelve [1]. Population growth has begun to slow, especially in developed countries, but global population is not expected to reach peak levels for at least thirty years [2][3]. In light of these trends, a natural question to ask is whether the Earth can support these kinds of increases in both population and per capita consumption. The population aspect of this is important because if we assume that available resources are finite, then a smaller population size may not solve the problem of overconsumption but it will slow demand for resources and give us more time to develop sustainable long-term solutions. Despite the intuitively clear relationship between population and resource consumption, the issue of overpopulation is one that has been largely ignored in scientific circles since the 1970s [4]. -

An Essay on the Ecological and Socio-Economic Effects of the Current and Future Global Human Population Size

An essay on the ecological and socio-economic effects of the current and future global human population size “The global human population is and will probably remain too large to allow for a sustainable use of the earth’s resources and an acceptable distribution of welfare” MSc Thesis By Jasper A.J. Eikelboom Supervised by dr. M. van Kuijk and prof. ir. N.D. van Egmond Utrecht University 27-09-2013 Abstract Since the dawn of civilization the world population has grown very slowly, but since the Industrial Revolution in 1750 and especially the Green Revolution around 1950 the growth rate increased dramatically. At the moment there are 7 billion people and in 2100 it is expected that there will be between 8.5 and 12 billion people. Currently we already overshoot the earth’s carrying capacity and this problem will become even larger in the future. Because of the global overpopulation many negative ecological and socio-economic effects occur at the moment. Land-use change, climate change, biodiversity loss, risk of epidemics, poor welfare distribution, resource scarcity and subsequent indirect effects such as factory farming and armed struggles for resources are caused by overpopulation. All these effects are long-lasting and many are irreversible. The longer we overshoot the carrying capacity of the earth and the larger the human population becomes, the worse the effects will be. It can thus be concluded that the global human population is and will probably remain too large to allow for a sustainable use of the earth’s resources and an equal distribution of the use of these resources. -

Scientists Hope to Breed Asian 'Unicorns' – If They Can Find Them

Scientists hope to breed Asian ‘unicorns’ – if they can find them Conservationists see only one hope for the saola: a risky captive breeding programme Jeremy Hance Thursday 10 August 2017 03.42 EDT n 1996, William Robichaud spent three weeks with Martha before she died. Robichaud I studied Martha – a beautiful, enigmatic, shy saola – with a scientist’s eye but also fell under the gracile animal’s spell as she ate out of his hand and allowed herself to be stroked. Captured by local hunters, Martha spent those final days in a Laotian village, doted on by Robichaud. Since losing Martha, Robichaud has become the coordinator of the Saola Working Group (SWG) at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). He has dedicated his life to saving this critically endangered species – and believes the best chance to achieve that now is through a captive breeding programme. “We need to act while there is still time,” he said adding that “seldom, if ever” are captive breeding programs begun too soon for species on the edge. “More likely, too late.” We just found the saola – and now we’re very close to losing it forever. Discovery Hardly a household name, the saola was one of the most astounding biological discoveries of the 20th Century. In 1992, a group of scientists met a local hunter in Vietnam who gave them a skull of something no biologist had ever seen before. The animal – the saola or Pseudoryx nghetinhensis – was a large-bodied terrestrial mammal (80-100kg) that somehow eluded science, though not local people, well into the information age. -

Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project

NAM NGIEP 1 HYDROPOWER PROJECT FINAL DRAFT REPORT 13 AUGUST 2016 A BIODIVERSITY RECONNAISSANCE OF A CANDIDATE OFFSET AREA FOR THE NAM NGIEP 1 HYDROPOWER PROJECT IN THE NAM MOUANE AREA, BOLIKHAMXAY PROVINCE Prepared by: Chanthavy Vongkhamheng1 and J. W. Duckworth2 1. Biodiversity Assessment Team Leader, and 2. Biodiversity Technical Advisor Presented to: The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Company Limited. Vientiane, Lao PDR. 30 June 2016 0 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................... 6 CONVENTIONS ................................................................................................................................... 7 NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 10 PRINCIPLES OF ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................................ 10 CONCEPTUAL BASIS FOR SELECTING A BIODIVERSITY OFFSET AREA ............................. 12 THE CANDIDATE OFFSET AREA ................................................................................................... 13 METHODS ........................................................................................................................................... 15 i. Village discussions ......................................................................................................................... -

Sexual Selection and Extinction in Deer Saloume Bazyan

Sexual selection and extinction in deer Saloume Bazyan Degree project in biology, Master of science (2 years), 2013 Examensarbete i biologi 30 hp till masterexamen, 2013 Biology Education Centre and Ecology and Genetics, Uppsala University Supervisor: Jacob Höglund External opponent: Masahito Tsuboi Content Abstract..............................................................................................................................................II Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 Sexual selection........................................................................................................................1 − Male-male competition...................................................................................................2 − Female choice.................................................................................................................2 − Sexual conflict.................................................................................................................3 Secondary sexual trait and mating system. .............................................................................3 Intensity of sexual selection......................................................................................................5 Goal and scope.....................................................................................................................................6 Methods................................................................................................................................................8 -

Discussing Population Concepts: Overpopulation Is a Necessary Word and an Inconvenient Truth

1 Discussing population concepts: Overpopulation is a necessary word and an inconvenient truth Frank Götmark*, Jane O’Sullivan, Philip Cafaro F.G., Department of Biology and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Box 463, SE-40530 Göteborg, Sweden. * Corresponding author, e-mail [email protected], phone +46702309315 J.O., School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane 4072, Australia., e- mail [email protected] P.C., School of Global Environmental Sustainability, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523, e-mail [email protected] Abstract In science, in the media, and in international communication by organizations such as the UN, the term ‘overpopulation’ is rarely used. Here we argue that it is an accurate description of our current reality, well backed up by scientific evidence. While the threshold defining human overpopulation will always be contested, overpopulation unequivocally exists where 1) people are displacing wild species so thoroughly, either locally or globally, that they are helping create a global mass extinction event; and where 2) people are so thoroughly degrading ecosystems that provide essential environmental services, that future human generations likely will have a hard time living decent lives. These conditions exist today in most countries around the world, and in the world as a whole. Humanity’s inability to recognize the role population growth has played in creating our environmental problems and the role population decrease could play in helping us solve them is a tremendous brake on environmental progress. While reducing excessive populations is not a panacea, it is necessary to create ecologically sustainable societies. -

Is Population Growth an Environmental Problem? Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Including It in Their Teaching

sustainability Article Is Population Growth an Environmental Problem? Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Including It in Their Teaching Iris Alkaher 1,2,* and Nurit Carmi 2 1 Faculty of Science, Kibbutzim College of Education Technology and the Arts, Tel Aviv 6250769, Israel 2 Department of Environmental Sciences, Tel-Hai Academic College, Upper Galilee 1220800, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 28 March 2019; Published: 3 April 2019 Abstract: Population growth (PG) is one of the drivers of the environmental crisis and underlies almost every environmental problem. Despite its causative role in environmental challenges, it has gained little attention from popular media, public and government agenda, or even from environmental organizations. There is a gap between the gravity of the problem and its relative absence from the public discourse that stems, inter alia, from the fact that the very discussion of the subject raises many sensitive, complex and ethical questions. The education system is a key player in filling this gap, and teachers have an opportunity to facilitate the discussion in this important issue. While educators mostly agree to include controversial environmental topics in school curricula, calls for addressing PG remain rare. This study explores teachers’ perspectives of PG as a problem and their attitudes towards including it in their teaching, focusing on environmental and non-environmental teachers. While perceiving PG as an environmental problem and supporting its inclusion in schools was significantly higher among the environmental-teachers, similar concerns were reported by all the teachers concerning engaging students in discourse around this controversial issue. -

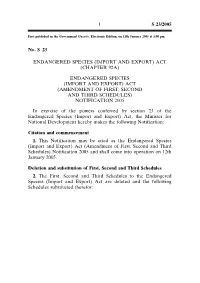

Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Chapter 92A)

1 S 23/2005 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 11th January 2005 at 5:00 pm. NO.S 23 ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (CHAPTER 92A) ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (AMENDMENT OF FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD SCHEDULES) NOTIFICATION 2005 In exercise of the powers conferred by section 23 of the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act, the Minister for National Development hereby makes the following Notification: Citation and commencement 1. This Notification may be cited as the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Amendment of First, Second and Third Schedules) Notification 2005 and shall come into operation on 12th January 2005. Deletion and substitution of First, Second and Third Schedules 2. The First, Second and Third Schedules to the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act are deleted and the following Schedules substituted therefor: ‘‘FIRST SCHEDULE S 23/2005 Section 2 (1) SCHEDULED ANIMALS PART I SPECIES LISTED IN APPENDIX I AND II OF CITES In this Schedule, species of an order, family, sub-family or genus means all the species of that order, family, sub-family or genus. First column Second column Third column Common name for information only CHORDATA MAMMALIA MONOTREMATA 2 Tachyglossidae Zaglossus spp. New Guinea Long-nosed Spiny Anteaters DASYUROMORPHIA Dasyuridae Sminthopsis longicaudata Long-tailed Dunnart or Long-tailed Sminthopsis Sminthopsis psammophila Sandhill Dunnart or Sandhill Sminthopsis Thylacinidae Thylacinus cynocephalus Thylacine or Tasmanian Wolf PERAMELEMORPHIA -

September 2019

Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics EJAIB Vol. 29 (5) September 2019 www.eubios.info ISSN 1173-2571 (Print) ISSN 2350-3106 (Online) Official Journal of the Asian Bioethics Association (ABA) Copyright ©2019 Eubios Ethics Institute (All rights reserved, for commercial reproductions). viewpoint. In the past three years a popular idea of false news, fake news, and politically biased discourse has been Contents page more evident in the print, media and social media groups. Editorial: Academic Freedom is an Essence of For centuries there have been institutions that try to limit Bioethical Discourse - Darryl Macer 153 discussion to their particular ideology, theology or Attempts by scientists to suppress discussion of passion. We still have these, and it is part of the overpopulation: A California case that celebration of human diversity itself when we have a full backired nicely 154 range of positions. We respect their freedom. - Stuart H. Hurlbert Academic Freedom is only possible through a climate Why denial of human overpopulation is a key barrier of open and transparent genuine discourse, using the full to a sustainable future 166 range of rational and emotional arguments that humans - Haydn Washington, Ian Lowe, Helen Kopnina have created. It is a foundation also of academic How research literature and media cover the role and associations, such as the Asian Bioethics Association, of image of disabled people in relation to academic institutions, and of the discipline of Bioethics. artiBicial intelligence and neuro-research 169 When academic institutions attempt to stiBle freedom - Rochelle Deloria, Aspen Lillywhite, Valentina Villamil of dialogue it usually backBires against them creating & Gregor Wolbring discontent, and the irst extended paper in this issue of Legacies of Love, Peace and Hope New Living Book 182 EJAIB by Stuart H. -

Ethical Implications of Population Growth and Reduction Tiana Sepahpour [email protected]

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Student Theses 2015-Present Environmental Studies Spring 5-10-2019 Ethical Implications of Population Growth and Reduction Tiana Sepahpour [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/environ_2015 Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Sepahpour, Tiana, "Ethical Implications of Population Growth and Reduction" (2019). Student Theses 2015-Present. 75. https://fordham.bepress.com/environ_2015/75 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses 2015-Present by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethical Implications of Population Growth and Reduction Tiana Sepahpour Fordham University Department of Environmental Studies and Philosophy May 2019 Abstract This thesis addresses the ethical dimensions of the overuse of the Earth’s ecosystem services and how human population growth exacerbates it, necessitating an ethically motivated reduction in human population size by means of changes in population policy. This policy change serves the goal of reducing the overall global population as the most effective means to alleviate global issues of climate change and resource abuse. Chapter 1 draws on the United Nations’ Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and other sources to document the human overuse and degradation of ecosystem services, including energy resources. Chapter 2 explores the history of energy consumption and climate change. Chapter 3 examines the economic impact of reducing populations and how healthcare and retirement plans would be impacted by a decrease in a working population. -

Population Explosion and Freshwater Crises

1 POPULATION EXPLOSION AND FRESHWATER CRISES Prof. Dr. Muhammed Salim Akhter MRCOG, FRCOG, FRCS, FACOG, FCPS, Ph. D, Dr. Shahzad Alam Khan Ph. D. Overview: On October 31, the world's 7 billionth person will be born. Each of us is part of that population. With the world growing by more than 200,000 people a day, it's hard to know where you fit in. Earth's population was just 2.2 billion in 1950. This rate of increase is alarming when compared with resources available. Unfortunately the increase is relatively more in the developing countries such as Pakistan where it has already touched 180 million figures. The resources for human survival such as water food energy and transport are already beginning to pose serious problems. The number of humans is expected to rise from seven billion in 2011 to at least nine billion by 2050, boosting demands for water that are already extreme in many countries and set to worsen through global warming. The record population can be viewed as a success because it means people are living longer — average life expectancy has increased from about 48 years in the early 1950s to about 68 in the first decade of the 21st century — and more children are surviving worldwide. Fig1: Shows world population growth curve while Fig2: Shows distribution and Fig4: Pakistan’s Population. Population: • Currently the world’s population is 6.7 billion. • Rate of growth is roughly 75 million per year. • On Oct, 21 (2011) it reached to 7 billion mark. • At this rate it is expected to reach 9.5 billion by 2050. -

The Saola's Battle for Survival on the Ho Chi Minh Trail

2013 THE SAOLA’S BAttLE FOR SURVIVAL ON THE HO CHI MINH TRAIL © David Hulse / WWF-Canon WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. Written and edited by Elizabeth Kemf, PhD. Published in August 2013 by WWF – World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund), Gland, Switzerland. Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © Text 2013 WWF All rights reserved. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. SAOLA SPAWNS DECADES OF SPECIES DISCOVERIES 7 3. THE BIG EIGHT OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY 9 4. THREATS: TRAPPING, ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE AND HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 11 5. TUG OF WAR ON THE HO CHI MINH TRAIL 12 6. DISCOVERIES AND EXTINCTIONS 14 7. WHAT IS BEING DONE TO SAVE THE SAOLA? 15 Forest guard training and patrols 15 Expanding and linking protected areas 16 Trans-boundary protected area project 16 The Saola Working Group (SWG) 17 Biodiversity surveys 17 Landscape scale conservation planning 17 Leeches reveal rare species survival 18 8. THE SAOLA’S TIPPING POINT 19 9. TACKLING THE ISSUES: WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE? 20 Unsustainable Hunting, Wildlife Trade And Restaurants 20 Illegal Logging And Export 22 Dams And Roads 22 10.