CEP97 Antibody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synergistic Genetic Interactions Between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Synergistic Genetic Interactions between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models Rory J. Olson,1 Katharina Hopp ,2 Harrison Wells,3 Jessica M. Smith,3 Jessica Furtado,1,4 Megan M. Constans,3 Diana L. Escobar,3 Aron M. Geurts,5 Vicente E. Torres,3 and Peter C. Harris 1,3 Due to the number of contributing authors, the affiliations are listed at the end of this article. ABSTRACT Background Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) are genetically distinct, with ADPKD usually caused by the genes PKD1 or PKD2 (encoding polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively) and ARPKD caused by PKHD1 (encoding fibrocys- tin/polyductin [FPC]). Primary cilia have been considered central to PKD pathogenesis due to protein localization and common cystic phenotypes in syndromic ciliopathies, but their relevance is questioned in the simple PKDs. ARPKD’s mild phenotype in murine models versus in humans has hampered investi- gating its pathogenesis. Methods To study the interaction between Pkhd1 and Pkd1, including dosage effects on the phenotype, we generated digenic mouse and rat models and characterized and compared digenic, monogenic, and wild-type phenotypes. Results The genetic interaction was synergistic in both species, with digenic animals exhibiting pheno- types of rapidly progressive PKD and early lethality resembling classic ARPKD. Genetic interaction be- tween Pkhd1 and Pkd1 depended on dosage in the digenic murine models, with no significant enhancement of the monogenic phenotype until a threshold of reduced expression at the second locus was breached. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplemental Information Proximity Interactions Among Centrosome

Current Biology, Volume 24 Supplemental Information Proximity Interactions among Centrosome Components Identify Regulators of Centriole Duplication Elif Nur Firat-Karalar, Navin Rauniyar, John R. Yates III, and Tim Stearns Figure S1 A Myc Streptavidin -tubulin Merge Myc Streptavidin -tubulin Merge BirA*-PLK4 BirA*-CEP63 BirA*- CEP192 BirA*- CEP152 - BirA*-CCDC67 BirA* CEP152 CPAP BirA*- B C Streptavidin PCM1 Merge Myc-BirA* -CEP63 PCM1 -tubulin Merge BirA*- CEP63 DMSO - BirA* CEP63 nocodazole BirA*- CCDC67 Figure S2 A GFP – + – + GFP-CEP152 + – + – Myc-CDK5RAP2 + + + + (225 kDa) Myc-CDK5RAP2 (216 kDa) GFP-CEP152 (27 kDa) GFP Input (5%) IP: GFP B GFP-CEP152 truncation proteins Inputs (5%) IP: GFP kDa 1-7481-10441-1290218-1654749-16541045-16541-7481-10441-1290218-1654749-16541045-1654 250- Myc-CDK5RAP2 150- 150- 100- 75- GFP-CEP152 Figure S3 A B CEP63 – – + – – + GFP CCDC14 KIAA0753 Centrosome + – – + – – GFP-CCDC14 CEP152 binding binding binding targeting – + – – + – GFP-KIAA0753 GFP-KIAA0753 (140 kDa) 1-496 N M C 150- 100- GFP-CCDC14 (115 kDa) 1-424 N M – 136-496 M C – 50- CEP63 (63 kDa) 1-135 N – 37- GFP (27 kDa) 136-424 M – kDa 425-496 C – – Inputs (2%) IP: GFP C GFP-CEP63 truncation proteins D GFP-CEP63 truncation proteins Inputs (5%) IP: GFP Inputs (5%) IP: GFP kDa kDa 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl Myc- 150- Myc- 100- CCDC14 KIAA0753 100- 100- 75- 75- GFP- GFP- 50- CEP63 50- CEP63 37- 37- Figure S4 A siCtl -

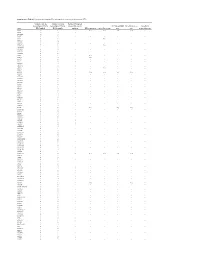

Supplementary Table S1. Prioritization of Candidate FPC Susceptibility Genes by Private Heterozygous Ptvs

Supplementary Table S1. Prioritization of candidate FPC susceptibility genes by private heterozygous PTVs Number of private Number of private Number FPC patient heterozygous PTVs in heterozygous PTVs in tumors with somatic FPC susceptibility Hereditary cancer Hereditary Gene FPC kindred BCCS samples mutation DNA repair gene Cancer driver gene gene gene pancreatitis gene ATM 19 1 - Yes Yes Yes Yes - SSPO 12 8 1 - - - - - DNAH14 10 3 - - - - - - CD36 9 3 - - - - - - TET2 9 1 - - Yes - - - MUC16 8 14 - - - - - - DNHD1 7 4 1 - - - - - DNMT3A 7 1 - - Yes - - - PKHD1L1 7 9 - - - - - - DNAH3 6 5 - - - - - - MYH7B 6 1 - - - - - - PKD1L2 6 6 - - - - - - POLN 6 2 - Yes - - - - POLQ 6 7 - Yes - - - - RP1L1 6 6 - - - - - - TTN 6 5 4 - - - - - WDR87 6 7 - - - - - - ABCA13 5 3 1 - - - - - ASXL1 5 1 - - Yes - - - BBS10 5 0 - - - - - - BRCA2 5 6 1 Yes Yes Yes Yes - CENPJ 5 1 - - - - - - CEP290 5 5 - - - - - - CYP3A5 5 2 - - - - - - DNAH12 5 6 - - - - - - DNAH6 5 1 1 - - - - - EPPK1 5 4 - - - - - - ESYT3 5 1 - - - - - - FRAS1 5 4 - - - - - - HGC6.3 5 0 - - - - - - IGFN1 5 5 - - - - - - KCP 5 4 - - - - - - LRRC43 5 0 - - - - - - MCTP2 5 1 - - - - - - MPO 5 1 - - - - - - MUC4 5 5 - - - - - - OBSCN 5 8 2 - - - - - PALB2 5 0 - Yes - Yes Yes - SLCO1B3 5 2 - - - - - - SYT15 5 3 - - - - - - XIRP2 5 3 1 - - - - - ZNF266 5 2 - - - - - - ZNF530 5 1 - - - - - - ACACB 4 1 1 - - - - - ALS2CL 4 2 - - - - - - AMER3 4 0 2 - - - - - ANKRD35 4 4 - - - - - - ATP10B 4 1 - - - - - - ATP8B3 4 6 - - - - - - C10orf95 4 0 - - - - - - C2orf88 4 0 - - - - - - C5orf42 4 2 - - - - -

Methods in and Applications of the Sequencing of Short Non-Coding Rnas" (2013)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Methods in and Applications of the Sequencing of Short Non- Coding RNAs Paul Ryvkin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, Genetics Commons, and the Molecular Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ryvkin, Paul, "Methods in and Applications of the Sequencing of Short Non-Coding RNAs" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 922. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/922 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/922 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Methods in and Applications of the Sequencing of Short Non-Coding RNAs Abstract Short non-coding RNAs are important for all domains of life. With the advent of modern molecular biology their applicability to medicine has become apparent in settings ranging from diagonistic biomarkers to therapeutics and fields angingr from oncology to neurology. In addition, a critical, recent technological development is high-throughput sequencing of nucleic acids. The convergence of modern biotechnology with developments in RNA biology presents opportunities in both basic research and medical settings. Here I present two novel methods for leveraging high-throughput sequencing in the study of short non- coding RNAs, as well as a study in which they are applied to Alzheimer's Disease (AD). The computational methods presented here include High-throughput Annotation of Modified Ribonucleotides (HAMR), which enables researchers to detect post-transcriptional covalent modifications ot RNAs in a high-throughput manner. In addition, I describe Classification of RNAs by Analysis of Length (CoRAL), a computational method that allows researchers to characterize the pathways responsible for short non-coding RNA biogenesis. -

Centrin2 Regulates CP110 Removal in Primary Cilium Formation

Published March 9, 2015 JCB: Report Centrin2 regulates CP110 removal in primary cilium formation Suzanna L. Prosser and Ciaran G. Morrison Centre for Chromosome Biology, School of Natural Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway, Galway, Ireland rimary cilia are antenna-like sensory microtubule ciliogenesis in chicken DT40 B lymphocytes required cen- structures that extend from basal bodies, plasma trin2. We disrupted CETN2 in human retinal pigmented P membrane–docked mother centrioles. Cellular qui- epithelial cells, and despite having intact centrioles, they escence potentiates ciliogenesis, but the regulation of basal were unable to make cilia upon serum starvation, show- body formation is not fully understood. We used reverse ing abnormal localization of distal appendage proteins genetics to test the role of the small calcium-binding pro- and failing to remove the ciliation inhibitor CP110. Knock- tein, centrin2, in ciliogenesis. Primary cilia arise in most down of CP110 rescued ciliation in CETN2-deficient cells. cell types but have not been described in lymphocytes. Thus, centrin2 regulates primary ciliogenesis through con- We show here that serum starvation of transformed, cul- trolling CP110 levels. Downloaded from tured B and T cells caused primary ciliogenesis. Efficient Introduction Primary cilia are crucial for several signal transduction path- the immune synapse, a membrane region at which cells of on April 19, 2017 ways (Goetz and Anderson, 2010). Their assembly is an or- the immune system contact their target cells, helps to estab- dered process that must be closely integrated with the cell cycle lish a specialized structure that has several similarities with cilia because of the dual roles of centrioles in ciliation and in mito- (Stinchcombe and Griffiths, 2014). -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

The Centriole Protein CEP76 Negatively Regulates PLK1 Activity in the Cytoplasm for Proper Mitotic Progression

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2020) 133, jcs241281. doi:10.1242/jcs.241281 RESEARCH ARTICLE The centriole protein CEP76 negatively regulates PLK1 activity in the cytoplasm for proper mitotic progression Yutaka Takeda, Kaho Yamazaki, Kaho Hashimoto, Koki Watanabe, Takumi Chinen*,‡ and Daiju Kitagawa*,‡ ABSTRACT are important for accurate mitotic progression (Golsteyn, 1995; Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) dynamically changes its localization and Schmucker and Sumara, 2014). Several factors regulate PLK1 plays important roles in proper mitotic progression. In particular, strict localization during mitosis. PLK1 is recruited to centrosomes in a control of cytoplasmic PLK1 is needed to prevent mitotic defects. CDK1-dependent manner (Lee et al., 2014). The initial recruitment However, the regulation of cytoplasmic PLK1 is not fully understood. In of PLK1 to kinetochores is mediated by its interaction with PBIP1 this study, we show that CEP76, a centriolar protein, physically (also known as CENPU; Kang et al., 2006). During anaphase, PLK1 interacts with PLK1 and tightly controls the activation of cytoplasmic binds to PRC1 and changes its localization to the midbody (Hu et al., PLK1 during mitosis in human cells. We found that removal of 2012). In addition, strict control of PLK1 in the cytoplasm is needed centrosomes induced ectopic aggregation of PLK1, which is highly to prevent its aggregation and mitotic defects (Mukhopadhyay and phosphorylated, in the cytoplasm during mitosis. Importantly, a Dasso, 2010; Schmit et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2016). However, the targeted RNAi screen revealed that depletion of CEP76 resulted in a detailed mechanisms through which the localization, expression and similar phenotype. -

Centrosome Impairment Causes DNA Replication Stress Through MLK3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.898684; this version posted January 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Centrosome impairment causes DNA replication stress through MLK3/MK2 signaling and R-loop formation Zainab Tayeh 1, Kim Stegmann 1, Antonia Kleeberg 1, Mascha Friedrich 1, Josephine Ann Mun Yee Choo 1, Bernd Wollnik 2, and Matthias Dobbelstein 1* 1) Institute of Molecular Oncology, Göttingen Center of Molecular Biosciences (GZMB), University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany 2) Institute of Human Genetics, University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany *Lead Contact. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M. D. (e-mail: [email protected]; ORCID 0000-0001-5052-3967) Running title: Centrosome integrity supports DNA replication Key words: Centrosome, CEP152, CCP110, SASS6, CEP152, Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), DNA replication, DNA fiber assays, R-loops, MLK3, MK2 alias MAPKAPK2, Seckel syndrome, microcephaly. Highlights: • Centrosome defects cause replication stress independent of mitosis. • MLK3, p38 and MK2 (alias MAPKAPK2) are signalling between centrosome defects and DNA replication stress through R-loop formation. • Patient-derived cells with defective centrosomes display replication stress, whereas inhibition of MK2 restores their DNA replication fork progression and proliferation. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.898684; this version posted January 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Is Cep70, a Centrosomal Protein with New Roles in Breast Cancer Dissemination and Metastasis, a Facilitator of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition?

Is Cep70, a centrosomal protein with new roles in breast cancer dissemination and metastasis, a facilitator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition? Pedro A. Lazo 1,2 1 Experimental Therapeutics and Translational Oncology Program, Instituto de Biología Molecular y Celular del Cáncer, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain 2 Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Salamanca (IBSAL), Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain Running title: Cep70 and EMT Disclosures: None declared. Contact address: [email protected] 1 Introduction Microtubules are driving mechanisms of chromosomes, intracellular organelle movement, and cell shape and motility. Microtubules are organized on centrosomes, which are assembled in microtubule-organizing centers (MTOC). In mitosis there is no nuclear envelope and centromeres associated to microtubules are mainly involved in chromosome redistribution into daughter cells. In differentiated cells the microtubule- organizing centers are dispersed in the cytoplasm (non centrosomal (ncMTOC)) and interact with the minus end of microtubules through γ-tubulin. 1 However, it is not known if the microtubule contribution to tumor biology is only by facilitating tumor aneuploidy. During tumor dissemination, a process not linked to cell division, important changes take place in cell shape and motility. Microtubules are very dynamic because of their inherent structural instability, and this plasticity facilitates their reorganization during the epithelial-mesenchymal -

Identification of 42 Genes Linked to Stage II Colorectal Cancer Metastatic Relapse

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 598; doi:10.3390/ijms17040598 S1 of S16 Supplementary Materials: Identification of 42 Genes Linked to Stage II Colorectal Cancer Metastatic Relapse Rabeah A. Al-Temaimi, Tuan Zea Tan, Makia J. Marafie, Jean Paul Thiery, Philip Quirke and Fahd Al-Mulla Figure S1. Cont. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 598; doi:10.3390/ijms17040598 S2 of S16 Figure S1. Mean expression levels of fourteen genes of significant association with CRC DFS and OS that are differentially expressed in normal colon compared to CRC tissues. Each dot represents a sample. Table S1. Copy number aberrations associated with poor disease-free survival and metastasis in early stage II CRC as predicted by STAC and SPPS combined methodologies with resident gene symbols. CN stands for copy number, whereas CNV is copy number variation. Region Cytoband % of CNV Count of Region Event Gene Symbols Length Location Overlap Genes chr1:113,025,076–113,199,133 174,057 p13.2 CN Loss 0.0 2 AKR7A2P1, SLC16A1 chr1:141,465,960–141,822,265 356,305 q12–q21.1 CN Gain 95.9 1 SRGAP2B MIR5087, LOC10013000 0, FLJ39739, LOC10028679 3, PPIAL4G, PPIAL4A, NBPF14, chr1:144,911,564–146,242,907 1,331,343 q21.1 CN Gain 99.6 16 NBPF15, NBPF16, PPIAL4E, NBPF16, PPIAL4D, PPIAL4F, LOC645166, LOC388692, FCGR1C chr1:177,209,428–177,226,812 17,384 q25.3 CN Gain 0.0 0 chr1:197,652,888–197,676,831 23,943 q32.1 CN Gain 0.0 1 KIF21B chr1:201,015,278–201,033,308 18,030 q32.1 CN Gain 0.0 1 PLEKHA6 chr1:201,289,154–201,298,247 9093 q32.1 CN Gain 0.0 0 chr1:216,820,186–217,043,421 223,235 q41 CN -

The Transformation of the Centrosome Into the Basal Body: Similarities and Dissimilarities Between Somatic and Male Germ Cells and Their Relevance for Male Fertility

cells Review The Transformation of the Centrosome into the Basal Body: Similarities and Dissimilarities between Somatic and Male Germ Cells and Their Relevance for Male Fertility Constanza Tapia Contreras and Sigrid Hoyer-Fender * Göttingen Center of Molecular Biosciences, Johann-Friedrich-Blumenbach Institute for Zoology and Anthropology-Developmental Biology, Faculty of Biology and Psychology, Georg-August University of Göttingen, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The sperm flagellum is essential for the transport of the genetic material toward the oocyte and thus the transmission of the genetic information to the next generation. During the haploid phase of spermatogenesis, i.e., spermiogenesis, a morphological and molecular restructuring of the male germ cell, the round spermatid, takes place that includes the silencing and compaction of the nucleus, the formation of the acrosomal vesicle from the Golgi apparatus, the formation of the sperm tail, and, finally, the shedding of excessive cytoplasm. Sperm tail formation starts in the round spermatid stage when the pair of centrioles moves toward the posterior pole of the nucleus. The sperm tail, eventually, becomes located opposed to the acrosomal vesicle, which develops at the anterior pole of the nucleus. The centriole pair tightly attaches to the nucleus, forming a nuclear membrane indentation. An Citation: Tapia Contreras, C.; articular structure is formed around the centriole pair known as the connecting piece, situated in the Hoyer-Fender, S. The Transformation neck region and linking the sperm head to the tail, also named the head-to-tail coupling apparatus or, of the Centrosome into the Basal in short, HTCA.