'Grand Theft Archive': a Quantitative Analysis of the State of Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 52-1, February

VOLUME 52.1 SPRING 2012 UN NGO Consultative Status ESCO & DPI 1981 2011-2012 BOARD MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President: Dr. Ludwig F. Lowenstein, England MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Fair Oak 004423 80692621 Dear Colleagues, friends and members of our family ICP, President Elect: Dr.Tara Pir, USA, Los Angeles, CA Another festival season and year is behind us and ahead of us, espe- (213) 381-1250 cially in the Northern Hemisphere are cold days and nights while in the Past President: : Dr.Ann Marie O’Roark, USA Southern Hemisphere it should be lovely and warm. Those who live in St. Augustine, FL the Southern Hemisphere are envied by those shivering in the cold. (904) 461 3382 Treasurer: Dr. Gerald L. Ga- Things are well on the way for attendance at conferences in mache, USA, St. Augustine, South Africa and Sevilla. Those who are coming to South Africa I FL would suggest the Fountain Hotel which is reasonably priced and of (904 ) 824- 5668 Secretary:Dr. Donna Goetz, good quality. It is near the convention centre. I would also consider the USA, Lombard, IL Hotel Viapol, in Sevilla which is also very convenient and near the University where the 630) 627-4969 ICP conference will be held. I will be arriving a day early and staying a day later after the DIRECTORS AT LARGE conference to meet you all and have a pre-convention informal get-together. As usual I reit- Term Expires in 2012 erate the importance of our finding new members who will hopefully be coming to the con- Prof. -

DVD / CD / MP Player

Owner’s Manual Owner’s ® DVD / CD / MP Player /MP /CD DVD T517 РУССКИЙ SVENSKA NEDERLANDS DEUTSCH ITALIANO ESPAÑOL FRANÇAIS ENGLISH IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS ENGLISH SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS FOR LATER USE. 14 Outdoor Antenna Grounding - If an outside antenna or cable system FOLLOW ALL WARNINGS AND INSTRUCTIONS MARKED ON THE is connected to the product, be sure the antenna or cable system is AUDIO EQUIPMENT. grounded so as to provide some protection against voltage surges and built-up static charges. Article 810 of the National Electrical Code, 1 Read instructions - All the safety and operating instructions should be ANSI/NFPA 70, provides information with regard to proper grounding read before the product is operated. of the mast and supporting structure, grounding of the lead-in wire 2 Retain instructions - The safety and operating instructions should be to an antenna discharge unit, size of grounding conductors, location FRANÇAIS ESPAÑOL retained for future reference. of antenna discharge unit, connection to grounding electrodes, and 3 Heed Warnings - All warnings on the product and in the operating requirements for the grounding electrode. instructions should be adhered to. 4 Follow Instructions - All operating and use instructions should be NOTE TO CATV SYSTEM INSTALLER followed. This reminder is provided to call the CATV system installer’s attention to Section 5 Cleaning - Unplug this product from the wall outlet before cleaning. 820-40 of the NEC which provides guidelines for proper grounding and, in Do not use liquid cleaners or aerosol cleaners. Use a damp cloth for particular, specifies that the cable ground shall be connected to the grounding cleaning. -

Hot Sounds of Summer Concert Lineup Is Hot!

PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE Sally Ellertson Public Information Officer 141 West Renfro Burleson, Texas 76028-4261 February 10, 2015 817-426-9622 F: 817-426-9390 [email protected] www.burlesontx.com It’s going to be a hot Hot Sounds of Summer concert series in 2015, starting with sophomore sensation Reagan James, best known for making it to the Top 10 on NBC’s “The Voice” headlining on May 29, and ending with crowd favorite Le Freak, bringing disco back to Burleson, on June 26. J.D. Monson, country/classic rock, is the headliner June 5. Journey fans don’t want to miss ESCAPE on June 12, and a 2014 favorite, Buddy Whittington, is bringing back the blues on June 19. The Hot Sounds of Summer showcases free 90-minute concerts that start at 7:30 p.m., every Friday between May 29 and June 26, at the intersection of Ellison and Wilson streets (124 W. Ellison St.). Between 4 p.m. and 10 p.m., Ellison Street is closed at Main Street and at Warren Street and Wilson is closed at the side entrance to city hall and at Wood Shopping Center. Come down early and eat at one of the more than half a dozen Old Town restaurants, then set up your lawn chairs and blankets in the street for the concert. Food and drink are allowed at the concerts, but patrons are strongly discouraged from bringing glass bottles, due to safety reasons. The 16-year-old James, a sophomore at Burleson’s Centennial High School, is an R&B/pop artist. -

Vc-300Hd-Introduction.Pdf

Now that digital broadcasting service areas are expanding, and with the appearance of high-definition content on Blu-ray and HD DVD media, there is a strong demand for high definition content production. Until these recent developments, HD content production had been comparatively simple, with the source of input being mainly limited to HD camera recordings. With television shifting to high definition and the rapid spread of high-definition video cameras for consumer use, location shooting in consumer HDV format with inexpensive cameras is becoming more popular. Meanwhile the transition to a tapeless era for broadcasting is underway. Overall, an extremely complex situation has arisen. If this had been a complete shift towards digital data in files handled by codecs, IP and the world of networking, this may not have presented so many challenges. In reality, we cannot ignore the world of real-time transmissions in which data streams of various formats are distributed via cable connection. When viewed as, “Hi-Def”, the various HD formats probably look the same to many. In reality, however, video from different sources are likely to have different resolutions, bit rates, and frame rates. Moreover, when these are transmitted, it may be physically impossible to access files with different formats. It is getting so that you can’t easily manage simple tasks like dubbing or monitoring. What is needed for this world of many formats is a multi-format converter that can convert from many formats to any other form. While it is possible to get devices that can specifically convert between just about any of the existing formats, for example between component and SDI, they are not cost effective or bi-directional. -

Journey Don't Stop Believin' / the Journey Story (An Audio Biography) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Journey Don't Stop Believin' / The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: Don't Stop Believin' / The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) Country: UK Released: 1982 Style: Pop Rock, Spoken Word, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1303 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1911 mb WMA version RAR size: 1118 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 412 Other Formats: MOD MP4 MP1 AAC MIDI TTA XM Tracklist Hide Credits Don't Stop Believin' A Producer – Kevin Elson, Mike StoneWritten-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. 4:08 Perry* The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) In The Morning B1 Written-By – G. Rolie*, R. Valory* To Play Some Music B2 Written-By – G. Rolie*, N. Schon* Saturday Nite B3 Written-By – Gregg Rolie Wheel In The Sky B4 Written-By – D. Valory*, Schon*, Fleischman* Feeling That Way B5 Written-By – Dunbar*, Rolie*, Perry* Anytime B6 Written-By – Rolie*, N. Schon*, Fleischman*, Silver*, R. Valory* Lovin' Touchin' Squeezin' B7 Written-By – S. Perry* When You're Alone (It Ain't Easy) B8 Written-By – N. Schon*, S. Perry* Someday Soon B9 Written-By – G. Rolie*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Any Way You Want It B10 Written-By – N. Schon*, S. Perry* Stone In Love B11 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Who's Crying Now B12 Written-By – J. Cain*, S. Perry* Mother Father B13 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Don't Stop Believin' B14 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – CBS Records Copyright (c) – CBS Records Pressed By – Orlake Records Published By – Screen Gems-EMI Music Ltd. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Liberal Arts Science $600 Million in Support of Undergraduate Science Education

Janelia Update |||| Roger Tsien |||| Ask a Scientist SUMMER 2004 www.hhmi.org/bulletin LIBERAL ARTS SCIENCE In science and teaching— and preparing future investigators—liberal arts colleges earn an A+. C O N T E N T S Summer 2004 || Volume 17 Number 2 FEATURES 22 10 10 A Wellspring of Scientists [COVER STORY] When it comes to producing science Ph.D.s, liberal arts colleges are at the head of the class. By Christopher Connell 22 Cells Aglow Combining aesthetics with shrewd science, Roger Tsien found a bet- ter way to look at cells—and helped to revolutionize several scientif-ic disciplines. By Diana Steele 28 Night Science Like to take risks and tackle intractable problems? As construction motors on at Janelia Farm, the call is out for venturesome scientists with big research ideas. By Mary Beth Gardiner DEPARTMENTS 02 I N S T I T U T E N E W S HHMI Announces New 34 Investigator Competition | Undergraduate Science: $50 Million in New Grants 03 PRESIDENT’S LETTER The Scientific Apprenticeship U P F R O N T 04 New Discoveries Propel Stem Cell Research 06 Sleeper’s Hold on Science 08 Ask a Scientist 27 I N T E R V I E W Toward Détente on Stem Cell Research 33 G R A N T S Extending hhmi’s Global Outreach | Institute Awards Two Grants for Science Education Programs 34 INSTITUTE NEWS Bye-Bye Bio 101 NEWS & NOTES 36 Saving the Children 37 Six Antigens at a Time 38 The Emergence of Resistance 40 39 Hidden Potential 39 Remembering Santiago 40 Models and Mentors 41 Tracking the Transgenic Fly 42 Conduct Beyond Reproach 43 The 1918 Flu: Case Solved 44 HHMI LAB BOOK 46 N O T A B E N E 49 INSIDE HHMI Dollars and Sense ON THE COVER: Nancy H. -

Further Contribution to the Siwalik Flora Froul the Koilabas Area, Western Nepal

P"t"cobo/(/lIisl 48 (1999) . 49-95 0031-0174/99/49-95 $200 Further contribution to the Siwalik flora froUl the Koilabas area, western Nepal 2 2 MAHESH PRASAD!, 1.S. ANTAL"!, I ,pp TRIPATHI AND VINAY KUMAR PANDEy JBirbal Salllli Inslirute of Paloeobo!any. 53 University Rood, LllcknOIV 226 007. Indio. JBotany Department. M.L.K. Post Crodllate College. Bairamplll; Uf!or Pradesh. Indio. (Received I February 1999: revised version accepted 10 June 1999) ABSTRACT Prasad M, Antal JS, Tripathi PP & Pandey VK 1999. Further contribution to the Siwalik tlora from the Koilabas area. western Nepal. Palaeobotanist 48( I) : 49-95 The present study on fossil plants comprising well preserved leaf and fruit impressions from the Siwalik sediments exposed near KoilJbas in western Nepal is the first detailed and systematic work. The tloral assemblage recovered from these sediments is impoverished both in quality and quantity as consti tuted by 25 species belonging [022 genera and 15 dicotyledonous families ofangiosperms. This assemblage adds significant data to the Siwalik Palaeobotany. On the basis of present assemblage as well as already known data from the area. the palaeoclimate. palaeoecology and phytogeography of the area during Mio Pliocene in the Himalayan foot hills have been deduced. The significance of the physiognomic characters of the fossil leaves in relation to climate has also been discussed. Key-words-Leaf & fruit impressions. Angiosperm, Morphotaxonomy. Siwalik (Churia) Formation. PalJeoclimate. Phytogeography, Koilabas. Nepal. mu~ ~ qftql:fi ~~ ~ Cfil11(T\ICSlI*1 ~ em ~IClIRtCfi Cl:;H~Ri\1fld -q ~~ ~, ~. \iffiChr ~~ ~, qRm ~ ~ ~ rn ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~~l11, ~ ~ ~<llfl 1B <N'"l<'!IClIH 1B f1q:;c \3RTCIftf B \JRPTc1 ~ ~~l1 ~ ~n<.l'R ~:op:[ ~~ \J1~ ffifucf '0i m \J1ffi g, CfJT 1B 11Ttzil1 B qn: Fcmfr '0i \3~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ \3~ Fc8Tr 1'fllT ~ I 0 B C1"nJ:1m\i1l\i '0i m1B \3:nm 'R g. -

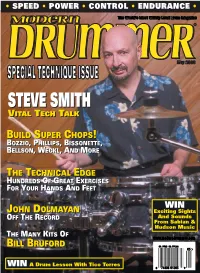

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

Gamasutra - Features - the History of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM

Gamasutra - Features - The History Of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM The History Of Activision By Jeffrey Fleming The Memo When David Crane joined Atari in 1977, the company was maturing from a feisty Silicon Valley start-up to a mass-market entertainment company. “Nolan Bushnell had recently sold to Warner but he was still around offering creative guidance. Most of the drug culture was a thing of the past and the days of hot-tubbing in the office were over,” Crane recalled. The sale to Warner Communications had given Atari the much-needed financial stability required to push into the home market with its new VCS console. Despite an uncertain start, the VCS soon became a retail sensation, bringing in hundreds of millions in profits for Atari. “It was a great place to work because we were creating cutting-edge home video games, and helping to define a new industry,” Crane remembered. “But it wasn’t all roses as the California culture of creativity was being pushed out in favor of traditional corporate structure,” Crane noted. Bushnell clashed with Warner’s board of directors and in 1978 he was forced out of the company that he had founded. To replace Bushnell, Warner installed former Burlington executive Ray Kassar as the company’s new CEO, a man who had little in common with the creative programmers at Atari. “In spite of Warner’s management, Atari was still doing very well financially, and middle management made promises of profit sharing and other bonuses. Unfortunately, when it came time to distribute these windfalls, senior management denied ever making such promises,” Crane remembered. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Mega Unlock Dvd Player All Multi Region Code Zone Free

This NON RESELLABLE document has been brought to you by: Best.Seller_1 @ eBay To find more items sold by me, go to: http://cgi6.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewSellersOtherItems&userid=best.seller_1 DVD Player Instruction 4KUS DVR-230 1. Power on the recorder 2. press SETUP 3. scroll down to EXIT 4. press 2 9 6 0 5. press ENTER 6. the region code will then appear 7. scroll sideways onto the region code and the list of all the available regions appears (region free and 1 thro 6) 8. select the one you want and press ENTER...and thats it A-trend AD-L528 1. switch on DVD player 2. press 'stop' on the remote 3. press '1','9','9','9' then 'enter' 4. the zone menu appears 5. select 'all' to de-regionize the player A-trend LE511 1. Switch on the DVD player 2. Press: STOP, 1, 9, 9, 9 3. The hidden menu appears. 4. Set the "Zone" field to ALL Aboss AB-6863 1. Power on the player. 2. Press Setup on remote. 3. Scroll down to 'Preferences' but do not select. 4. Press the left key five (5) times. 5. 'Verson' will appear in the menu. 6. Select Version. 7. Set region code to 0 (Multiregion). 8. Exit setup. 9. Power off player from unit (not from remote) for 20 seconds. Acoustic Solutions 1. Open tray & press 9 7 3 5. AS8099 2. From here you can set the unit to region 0-6, and also set parental level and password. Acoustic Solutions Method 1: DVD150AS 1.