Forest Diseases and Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID. The project has been financed by the CITES Secretariat with funds from the European Union Consulting objectives: TO SELECT INTERNATIONAL OR NATIONAL XYLARIUM OR WOOD COLLECTIONS REGISTERED AT THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOOD ANATOMISTS – IAWA THAT HAVE A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER OF SPECIES AND SPECIMENS OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA TO BE ANALYZED BY NIRS TECHNOLOGY. Consultant: VERA TERESINHA RAUBER CORADIN Dra English translation: ADRIANA COSTA Dra Affiliations: - Forest Products Laboratory, Brazilian Forest Service (LPF-SFB) - Laboratory of Automation, Chemometrics and Environmental Chemistry, University of Brasília (AQQUA – UnB) - Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC-DF MAY, 2020 Brasília – Brazil 1 Project number: S1-32QTL-000018 Host Country: Brazilian Government Executive agency: Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC Project coordinator: Dra. Tereza C. M. Pastore Project start: September 2019 Project duration: 24 months 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 05 2. THE SPECIES OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA 05 3. MATERIAL AND METHODS 3.1 NIRS METHODOLOGY AND SPECTRA COLLECTION 07 3.2 CRITERIA FOR SELECTING XYLARIA TO BE VISITED TO OBTAIN SPECTRAS 07 3 3 TERMINOLOGY 08 4. RESULTS 4.1 CONTACTED XYLARIA FOR COLLECTION SURVEY 10 4.1.1 BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 10 4.1.2 INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 11 4.2 SELECTED XYLARIA 11 4.3 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 13 4.4 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 14 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 6. REFERENCES 20 APPENDICES 22 APPENDIX I DALBERGIA IN BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 22 CACAO RESEARCH CENTER – CEPECw 22 EMÍLIO GOELDI MUSEUM – M. -

Rosewood) to CITES Appendix II.2 the New Listings Entered Into Force on January 2, 2017

Original language: English CoP18 Inf. 50 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Geneva (Switzerland), 17-28 August 2019 IMPLEMENTING CITES ROSEWOOD SPECIES LISTINGS: A DIAGNOSTIC GUIDE FOR ROSEWOOD RANGE STATES This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the World Resources Institute in relation to agenda item 74.* * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP18 Inf. 50 – p. 1 Draft for Comment August 2019 Implementing CITES Rosewood Species Listings A Diagnostic Guide for Rosewood Range States Charles Victor Barber Karen Winfield DRAFT August 2019 Corresponding Author: Charles Barber [email protected] Draft for Comment August 2019 INTRODUCTION The 17th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP-17) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), held in South Africa during September- October 2016, marked a turning point in CITES’ treatment of timber species. While a number of tree species had been brought under CITES regulation over the previous decades1, COP-17 saw a marked expansion of CITES timber species listings. The Parties at COP-17 listed the entire Dalbergia genus (some 250 species, including many of the most prized rosewoods), Pterocarpus erinaceous (kosso, a highly-exploited rosewood species from West Africa) and three Guibourtia species (bubinga, another African rosewood) to CITES Appendix II.2 The new listings entered into force on January 2, 2017. -

Ecology, and Population Status of Dalbergia Latifolia from Indonesia

A REVIEW ON TAXONOMY, BIOLOGY, ECOLOGY, AND POPULATION STATUS OF DALBERGIA LATIFOLIA FROM INDONESIA K U S U M A D E W I S R I Y U L I T A , R I Z K I A R Y F A M B A Y U N , T I T I E K S E T Y A W A T I , A T O K S U B I A K T O , D W I S E T Y O R I N I , H E N T I H E N D A L A S T U T I , A N D B A Y U A R I E F P R A T A M A A review on Taxonomy, Biology, Ecology, and Population Status of Dalbergia latifolia from Indonesia Kusumadewi Sri Yulita, Rizki Ary Fambayun, Titiek Setyawati, Atok Subiakto, Dwi Setyo Rini, Henti Hendalastuti, and Bayu Arief Pratama Introduction Dalbergia latifolia Roxb. (Fabaceae) is known as sonokeling in Indonesia. The species may not native to Indonesia but have been naturalised in several islands of Indonesia since it was introduced from India (Sunarno 1996; Maridi et al. 2014; Arisoesilaningsih and Soejono 2015; Adema et al. 2016;). The species has beautiful dark purple heartwood (Figure 1). The wood is extracted to be manufactured mainly for musical instrument (Karlinasari et al. 2010). At present, the species have been cultivated mainly in agroforestry (Hani and Suryanto 2014; Mulyana et al., 2017). The main distribution of species in Indonesia including Java and West Nusa Tenggara (Djajanti 2006; Maridi et al. -

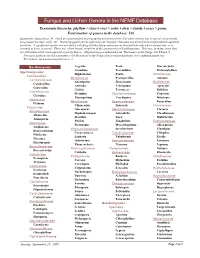

9B Taxonomy to Genus

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

HONGOS ASCOCIADOS AL BOSQUE RELICTO DE Fagus Grandifolia Var

INSTITUTO POLITÉCNICO NACIONAL ESCUELA NACIONAL DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS “HONGOS ASCOCIADOS AL BOSQUE RELICTO DE Fagus grandifolia var. mexicana EN EL MUNICIPIO DE ZACUALTIPAN, HIDALGO” T E S I S QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE BIÓLOGO P R E S E N T A ARANTZA AGLAE RODRIGUEZ SALAZAR DIRECTORA: DRA. TANIA RAYMUNDO OJEDA CODIRECTOR: DR. RICARDO VALENZUELA GARZA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, MARZO 2016 El presente trabajo se realizó en el Laboratorio de Micología del Departamento de Botánica de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas de Instituto Politécnico Nacional con apoyo de los proyectos SIP-IPN: INMUJERES-2012-02-198333, “EMPODERAMIENTO ECONÓMICO DE LAS HONGUERAS DEL MUNICIPIO DE ACAXOCHITLÁN, HGO. A TRAVÉS DE PROCESOS ORGANIZATIVOS PARA LA ELABORACIÓN DE PRODUCTOS ALIMENTICIOS A BASE DE HONGOS SILVESTRES Y CULTIVO ORGÁNICO DE PLANTAS” “Diversidad de los hongos del bosque mesófilo de montaña en México, ecosistema en peligro de extinción. Estrategias para su conservación y restauración”. SIP-20151530 (IPN) en el período enero-diciembre 2015. “Diversidad de los hongos del bosque mesófilo de montaña en México, ecosistema en peligro de extinción. Estrategias para su conservación y restauración Fase II”. SIP-20161166 en el período enero-diciembre 2015. En el período enero-diciembre 2016. “Hongos de los bosques templados y tropicales de Mexico su ecología, importancia forestal y médica en México” Fase I. SIP-20150540 (IPN) en el período enero-diciembre 2015. “Hongos de los bosques templados y tropicales de Mexico su ecología, importancia forestal y médica en México” Fase II. SIP-20161164 en el período enero-diciembre 2015. 4 INDICE PÁG. RESUMEN.……………………………………………………………………... 1 I. -

Disease Survey in Nurseries and Plantations of Forest Tree Species Grown in Kerala

KFRI Research Report 36 DISEASE SURVEY IN NURSERIES AND PLANTATIONS OF FOREST TREE SPECIES GROWN IN KERALA J.K.Sharma C.Mohanan E.J.Maria Florence KERALA FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE PEECHI, THRISSUR December 1985 Pages: 268 CONTENTS Page File Abstract 1 r. 36.2 Subject index i r. 36.9 1 Introduction 3 r.36.3 2 Materials and methods 6 r.36.4 3 Results 15 r.36.5 4 Discussion and conclusion 227 r.36.6 5 References 233 r.36.7 6 Appendix 244 r.36.8 ABSTRACT During the disease survey in Tectona grandis, Bombax ceiba, Ailanthus triphysa, Gmelina arborea. Dalbergia latifolia, Ochroma pyramidale and Eucalyptus spp. a total of 65 pathogenic and 13 other diseases (unknown etiology, non-infectious and phanerogamic parasite) were recorded. With these diseases altogether 88 pathogens were associated, of which 64 are new host record, including seven new species viz. Pseudoepicoccum tectonae and Phoinopsis variosporum on T, grandis, Meliola ailan thii on A. triphysa, Griphospharria gmelinae on G. arborca, Physalospora dalbergiae on D. latifolia and Cytospora eucalypti and Valsa eucalypticola on Eucalyptus spp., while 29 are first record from India, T. grandis had fifteen diseases, two in nursery and fourteen in plantations; one being common to both. Ten organisms were associated with these diseases; mostly causing foliar damage; six pathogens are new host record and four first record from India. None of the two diseases in nurseries were serious whereas in plantations die -back caused by insect-fungus complex and a phanerogamic parasite, Dendrop- hthoe falcata were serious diseases capable of causing large-scale destruction. -

The Sally Walker Conservation Fund at Zoo Outreach Organization to Continue Key Areas of Her Interest

Building evidence for conservaton globally Journal of Threatened Taxa ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) 26 November 2019 (Online & Print) PLATINUM Vol. 11 | No. 14 | 14787–14926 OPEN ACCESS 10.11609/jot.2019.11.14.14787-14926 J TT www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online); ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Publisher Host Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society Zoo Outreach Organizaton www.wild.zooreach.org www.zooreach.org No. 12, Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampat - Kalapat Road, Saravanampat, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Ph: +91 9385339863 | www.threatenedtaxa.org Email: [email protected] EDITORS English Editors Mrs. Mira Bhojwani, Pune, India Founder & Chief Editor Dr. Fred Pluthero, Toronto, Canada Dr. Sanjay Molur Mr. P. Ilangovan, Chennai, India Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development (WILD) Society & Zoo Outreach Organizaton (ZOO), 12 Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampat, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, Web Design India Mrs. Latha G. Ravikumar, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, India Deputy Chief Editor Typesetng Dr. Neelesh Dahanukar Indian Insttute of Science Educaton and Research (IISER), Pune, Maharashtra, India Mr. Arul Jagadish, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Mrs. Radhika, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Managing Editor Mrs. Geetha, ZOO, Coimbatore India Mr. B. Ravichandran, WILD/ZOO, Coimbatore, India Mr. Ravindran, ZOO, Coimbatore India Associate Editors Fundraising/Communicatons Dr. B.A. Daniel, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Mrs. Payal B. Molur, Coimbatore, India Dr. Mandar Paingankar, Department of Zoology, Government Science College Gadchiroli, Chamorshi Road, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra 442605, India Dr. Ulrike Streicher, Wildlife Veterinarian, Eugene, Oregon, USA Editors/Reviewers Ms. Priyanka Iyer, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Subject Editors 2016-2018 Fungi Editorial Board Ms. Sally Walker Dr. -

Polypore Diversity in North America with an Annotated Checklist

Mycol Progress (2016) 15:771–790 DOI 10.1007/s11557-016-1207-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Polypore diversity in North America with an annotated checklist Li-Wei Zhou1 & Karen K. Nakasone2 & Harold H. Burdsall Jr.2 & James Ginns3 & Josef Vlasák4 & Otto Miettinen5 & Viacheslav Spirin5 & Tuomo Niemelä 5 & Hai-Sheng Yuan1 & Shuang-Hui He6 & Bao-Kai Cui6 & Jia-Hui Xing6 & Yu-Cheng Dai6 Received: 20 May 2016 /Accepted: 9 June 2016 /Published online: 30 June 2016 # German Mycological Society and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 Abstract Profound changes to the taxonomy and classifica- 11 orders, while six other species from three genera have tion of polypores have occurred since the advent of molecular uncertain taxonomic position at the order level. Three orders, phylogenetics in the 1990s. The last major monograph of viz. Polyporales, Hymenochaetales and Russulales, accom- North American polypores was published by Gilbertson and modate most of polypore species (93.7 %) and genera Ryvarden in 1986–1987. In the intervening 30 years, new (88.8 %). We hope that this updated checklist will inspire species, new combinations, and new records of polypores future studies in the polypore mycota of North America and were reported from North America. As a result, an updated contribute to the diversity and systematics of polypores checklist of North American polypores is needed to reflect the worldwide. polypore diversity in there. We recognize 492 species of polypores from 146 genera in North America. Of these, 232 Keywords Basidiomycota . Phylogeny . Taxonomy . species are unchanged from Gilbertson and Ryvarden’smono- Wood-decaying fungus graph, and 175 species required name or authority changes. -

Tarset and Greystead Biological Records

Tarset and Greystead Biological Records published by the Tarset Archive Group 2015 Foreword Tarset Archive Group is delighted to be able to present this consolidation of biological records held, for easy reference by anyone interested in our part of Northumberland. It is a parallel publication to the Archaeological and Historical Sites Atlas we first published in 2006, and the more recent Gazeteer which both augments the Atlas and catalogues each site in greater detail. Both sets of data are also being mapped onto GIS. We would like to thank everyone who has helped with and supported this project - in particular Neville Geddes, Planning and Environment manager, North England Forestry Commission, for his invaluable advice and generous guidance with the GIS mapping, as well as for giving us information about the archaeological sites in the forested areas for our Atlas revisions; Northumberland National Park and Tarset 2050 CIC for their all-important funding support, and of course Bill Burlton, who after years of sharing his expertise on our wildflower and tree projects and validating our work, agreed to take this commission and pull everything together, obtaining the use of ERIC’s data from which to select the records relevant to Tarset and Greystead. Even as we write we are aware that new records are being collected and sites confirmed, and that it is in the nature of these publications that they are out of date by the time you read them. But there is also value in taking snapshots of what is known at a particular point in time, without which we have no way of measuring change or recognising the hugely rich biodiversity of where we are fortunate enough to live. -

Biodiversity of Plant Pathogenic Fungi in the Kerala Part of the Western Ghats

Biodiversity of Plant Pathogenic Fungi in the Kerala part of the Western Ghats (Final Report of the Project No. KFRI 375/01) C. Mohanan Forest Pathology Discipline Forest Protection Division K. Yesodharan Forest Botany Discipline Forest Ecology & Biodiversity Conservation Division KFRI Kerala Forest Research Institute An Institution of Kerala State council for Science, Technology and Environment Peechi 680 653 Kerala January 2005 0 ABSTRACT OF THE PROJECT PROPOSAL 1. Project No. : KFRI/375/01 2. Project Title : Biodiversity of Plant Pathogenic Fungi in the Kerala part of the Western Ghats 3. Objectives: i. To undertake a comprehensive disease survey in natural forests, forest plantations and nurseries in the Kerala part of the Western Ghats and to document the fungal pathogens associated with various diseases of forestry species, their distribution, and economic significance. ii. To prepare an illustrated document on plant pathogenic fungi, their association and distribution in various forest ecosystems in this region. 4. Date of commencement : November 2001 5. Date of completion : October 2004 6. Funding Agency: Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………….. 3 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….. 6 Materials and Methods…………………………………………………….……... 11 Results and Discussion…………………………………………………….……... 15 Diversity of plant pathogenic fungi in different forest ecosystems ……………. 27 West coast tropical evergreen forests…………………………………..….. -

(Leguminosae-Papilionoideae) 17. the Genus Dalbergia

Blumea 61, 2016: 186–206 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/000651916X693905 Notes on Malesian Fabaceae (Leguminosae-Papilionoideae) 17. The genus Dalbergia F. Adema1, H. Ohashi2, B. Sunarno†3 Key words Abstract A systematic treatment of the genus Dalbergia for the Flora Malesiana (FM) region is presented. The treat- ment includes a genus description, two keys to the species, an enumeration of the species present in the FM-area Dalbergia with names and synonyms, details of distribution, habitat and ecology and where needed some notes, three new Leguminosae (Fabaceae) species (D. minutiflora, D. pilosa, D. ramosii) are described. A new name for D. polyphylla is proposed (D. multifolio- Malesia lata). The paper also contains an overview of the names, a list of collections seen and references to the literature. new species Papilionoideae Published on 15 November 2016 INTRODUCTION Characteristic for Dalbergia are the usually alternate leaflets, the often small inflorescences (panicles or racemes), the generally Dalbergia L.f. is a large genus (c. 185 species) belonging to small flowers and the very small anthers opening by short slits the tribe Dalbergieae of the subfamily Papilionoideae of the that slowly enlarge. The wings are usually sculpted outside family Leguminosae. The genus is widespread in the old and (see also Stirton 1981), at least in the species that are known new world tropics. Dalbergia and the Dalbergieae are members in flower. As far as we know now only D. junghuhnii Benth. and of the monophyletic ‘Dalbergioid’ clade (Lavin et al. 2001). D. bintuluensis Sunarno & H.Ohashi have non-sculpted wings According to the analyses of Lavin et al. -

Notes, Outline and Divergence Times of Basidiomycota

Fungal Diversity (2019) 99:105–367 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-019-00435-4 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,- volV) Notes, outline and divergence times of Basidiomycota 1,2,3 1,4 3 5 5 Mao-Qiang He • Rui-Lin Zhao • Kevin D. Hyde • Dominik Begerow • Martin Kemler • 6 7 8,9 10 11 Andrey Yurkov • Eric H. C. McKenzie • Olivier Raspe´ • Makoto Kakishima • Santiago Sa´nchez-Ramı´rez • 12 13 14 15 16 Else C. Vellinga • Roy Halling • Viktor Papp • Ivan V. Zmitrovich • Bart Buyck • 8,9 3 17 18 1 Damien Ertz • Nalin N. Wijayawardene • Bao-Kai Cui • Nathan Schoutteten • Xin-Zhan Liu • 19 1 1,3 1 1 1 Tai-Hui Li • Yi-Jian Yao • Xin-Yu Zhu • An-Qi Liu • Guo-Jie Li • Ming-Zhe Zhang • 1 1 20 21,22 23 Zhi-Lin Ling • Bin Cao • Vladimı´r Antonı´n • Teun Boekhout • Bianca Denise Barbosa da Silva • 18 24 25 26 27 Eske De Crop • Cony Decock • Ba´lint Dima • Arun Kumar Dutta • Jack W. Fell • 28 29 30 31 Jo´ zsef Geml • Masoomeh Ghobad-Nejhad • Admir J. Giachini • Tatiana B. Gibertoni • 32 33,34 17 35 Sergio P. Gorjo´ n • Danny Haelewaters • Shuang-Hui He • Brendan P. Hodkinson • 36 37 38 39 40,41 Egon Horak • Tamotsu Hoshino • Alfredo Justo • Young Woon Lim • Nelson Menolli Jr. • 42 43,44 45 46 47 Armin Mesˇic´ • Jean-Marc Moncalvo • Gregory M. Mueller • La´szlo´ G. Nagy • R. Henrik Nilsson • 48 48 49 2 Machiel Noordeloos • Jorinde Nuytinck • Takamichi Orihara • Cheewangkoon Ratchadawan • 50,51 52 53 Mario Rajchenberg • Alexandre G.