DAVID A. WOLF June 23, 1998 Interviewers: Rebecca Wright, Paul Rollins, Mark Davison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Foale

NASA-5 Michael Foale | Collision and Recovery | Foale Bio | Needed on Mir | Meanwhile | Collision and Recovery Mike Foale went to Mir full of enthusiasm in spite of the fire and other problems during the NASA-4 increment. He expected hard work, some discomfort, and many challenges; and he hoped to integrate himself fully into the Mir-23 crew. The challenges became enormous when a Progress resupply vehicle accidentally rammed the space station, breaching the Back to Spektr module and causing a dangerous depressurization. The NASA-5 Mir-23 crew worked quickly to save the station; and in the TOC troubled months that followed, Foale set an example of how to face the more dangerous possibilities of spaceflight. Meanwhile on the ground, NASA’s Mir operations were changing, too. In part because of the problems, Foale’s NASA-5 increment catalyzed a broader and deeper partnership with the Russian Space Agency. Mike Foale’s diverse cultural, educational, and family background helped him adapt to his life onboard Mir. Born in England in 1957 to a Royal Air Force pilot father and an American mother, his early childhood included living overseas on Royal Air Force bases. An English boarding school education taught him how to get along with strangers; and, as a youth, he wrote his own plan for the future of spaceflight. At Cambridge University, Foale earned a Bachelor of Arts in physics and a doctorate in astrophysics. But, in the midst of this progress, disaster struck. Foale was driving through Yugoslavia with his fiance and brother when an auto accident took their lives but spared his own. -

Scott Parazynski 2016 U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame Inductee

Scott Parazynski 2016 U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame Inductee Scott E. Parazynski (M.D.) was selected as a NASA astronaut in March 1992. A veteran of five Space Shuttle flights, Parazynski has logged more than 1,381 hours in space, including more than 47 hours on seven spacewalks. Parazynski first flew in space on Nov. 3, 1994, on board STS-66 Atlantis. The STS-66 Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science-3 (ATLAS-3) mission was part of an on- going program to determine the Earth’s energy balance and atmospheric change over an 11-year solar cycle, particularly with respect to humanity’s impact on global-ozone distribution. The crew successfully evaluated the Interlimb Resistance Device, a free-floating exercise he co- invented to prevent musculoskeletal atrophy in microgravity. As flight engineer of Atlantis, Parazynski returned to space on STS-86, which launched from Kennedy Space Center on Sept. 25, 1997. This was the seventh mission to rendezvous and dock with the Russian Space Station Mir. Highlights of the mission included the exchange of U.S. crew members Mike Foale and David Wolf and the first shuttle-based joint American-Russian spacewalk. The crew also deployed the Spektr Solar Array Cap, which was designed to be used in a future Mir spacewalk to seal a leak in the Spektr module’s damaged hull. Parazynski’s next flight into space was on Oct. 29, 1998, aboard STS-95, Discovery with Senator John Glenn. During the nine-day mission, the crew supported a variety of research payloads, including the deployment of the Spartan solar-observing spacecraft (in which Parazynski navigated) and the testing of the Hubble Space Telescope Orbital Systems Test Platform. -

2020 Annual Report

Ensure that the United States continues its commitment to NASA’s programs of record and maintains American leadership in human space exploration, space science, space commerce and technology. 2020 ANNUAL REPORT A Message from Leadership The Coalition for Deep Space Exploration (CDSE) has provided yearly activity reports to our members for the past several years, but this year we are kicking off what will now be our “Annual Report,” highlighting milestones and activities immediately past. This is our inaugural issue. It goes without saying that 2020 was a year to remember, full of challenges, but also full of promise. As with the nation and the world, this was also the case in space. Our national programs in space continue to move full speed ahead. The year saw final testing of the first Orion crew capsule, destined to take humans farther into the solar system than ever before. The Space Launch System (SLS) entered final testing before shipping to NASA Kennedy Space Center, where the Exploration Ground Systems will process and integrate Orion and SLS for their first launch together in late 2021. Meanwhile, the James Webb Space Telescope completed a comprehensive test program with a scheduled launch also in 2021. At the same time, progress continued on the lunar Gateway and the Human Landing Systems, which will enable human presence around and on the Moon. The Mars Perseverance rover is scheduled to land on the Red Planet on February 18. Other NASA science missions span our solar system and beyond, contribute to our knowledge of the universe, the origins of our planet, and ultimately, where we are going as we face the challenges of a changing Earth. -

Shuttle Missions 1981-99.Pdf

1 2 Table of Contents Flight Page Flight Page 1981 STS-49 .................................................................................... 24 STS-1 ...................................................................................... 5 STS-50 .................................................................................... 25 STS-2 ...................................................................................... 5 STS-46 .................................................................................... 25 STS-47 .................................................................................... 26 1982 STS-52 .................................................................................... 26 STS-3 ...................................................................................... 5 STS-53 .................................................................................... 27 STS-4 ...................................................................................... 6 STS-5 ...................................................................................... 6 1993 1983 STS-54 .................................................................................... 27 STS-6 ...................................................................................... 7 STS-56 .................................................................................... 28 STS-7 ...................................................................................... 7 STS-55 ................................................................................... -

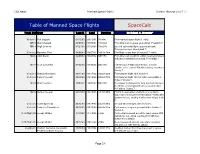

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

U.S. and Russian Human Space Flights and Russian Human U.S

APPENDIX C 79 U.S. and Russian Human Space Flights 1999 Year Fiscal Activities 1961–September 30, 1999 Spacecraft Launch Date Crew Flight Time Highlights (days:hrs:min) Vostok 1 Apr. 12, 1961 Yury A. Gagarin 0:1:48 First human flight. Mercury-Redstone 3 May 5, 1961 Alan B. Shepard, Jr. 0:0:15 First U.S. flight; suborbital. Mercury-Redstone 4 July 21, 1961 Virgil I. Grissom 0:0:16 Suborbital; capsule sank after landing; astronaut safe. Vostok 2 Aug. 6, 1961 German S. Titov 1:1:18 First flight exceeding 24 hrs. Mercury-Atlas 6 Feb. 20, 1962 John H. Glenn, Jr. 0:4:55 First American to orbit. Mercury-Atlas 7 May 24, 1962 M. Scott Carpenter 0:4:56 Landed 400 km beyond target. Vostok 3 Aug. 11, 1962 Andriyan G. Nikolayev 3:22:25 First dual mission (with Vostok 4). Vostok 4 Aug. 12, 1962 Pavel R. Popovich 2:22:59 Came within 6 km of Vostok 3. Mercury-Atlas 8 Oct. 3, 1962 Walter M. Schirra, Jr. 0:9:13 Landed 8 km from target. Mercury-Atlas 9 May 15, 1963 L. Gordon Cooper, Jr. 1:10:20 First U.S. flight exceeding 24 hrs. Vostok 5 June 14, 1963 Valery F. Bykovskiy 4:23:6 Second dual mission (with Vostok 6). Vostok 6 June 16, 1963 Valentina V. Tereshkova 2:22:50 First woman in space; within 5 km of Vostok 5. Voskhod 1 Oct. 12, 1964 Vladimir M. Komarov 1:0:17 First three-person crew. Konstantin P. Feoktistov Boris G. -

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Collection, 1911–2002

Collection # P 0395 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION COLLECTION, 1911–2002 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Pamela Tranfield 27 January 2003 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 2 folders COLLECTION: COLLECTION 1911–2002 DATES: PROVENANCE: Jay Small Postcard Collection (P 0391), John J. Small, 937 N. Indianapolis, IN, 24 September 1999; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, January 2003 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE None FORMATS: RELATED Jay Small Postcard Collection (P 0391) HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 1999.0679; 2003.0174 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Dr. David A. Wolf (b. 23 August 1956), the son of Dr. and Mrs. Harry Wolf, was born and raised in Indianapolis, Ind. Wolf graduated from North Central High School (Indianapolis) and received a bachelor of science degree from Purdue University (Lafayette) in 1978. In 1982 he completed a doctorate of medicine degree at Indiana University (Bloomington). Wolf joined the Medical Sciences Division, Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, in 1983. He was selected as a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) astronaut in January 1990. Sources: Material in the collection. “Astronaut Bio: David A. Wolf.” National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/htmlbios/wolf.html. Accessed 23 January 2003 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The collection contains two printed postcards depicting Indiana University Medical Center and Purdue University. -

Space Reporter's Handbook Mission Supplement

CBS News Space Reporter's Handbook - Mission Supplement Page 1 The CBS News Space Reporter's Handbook Mission Supplement Shuttle Mission STS-127/ISS-2JA: Station Assembly Enters the Home Stretch Written and Produced By William G. Harwood CBS News Space Analyst [email protected] CBS News 6/15/09 Page 2 CBS News Space Reporter's Handbook - Mission Supplement Revision History Editor's Note Mission-specific sections of the Space Reporter's Handbook are posted as flight data becomes available. Readers should check the CBS News "Space Place" web site in the weeks before a launch to download the latest edition: http://www.cbsnews.com/network/news/space/current.html DATE RELEASE NOTES 06/10/09 Initial STS-127 release 06/15/09 Updating to reflect launch delay to 6/17/09 Introduction This document is an outgrowth of my original UPI Space Reporter's Handbook, prepared prior to STS-26 for United Press International and updated for several flights thereafter due to popular demand. The current version is prepared for CBS News. As with the original, the goal here is to provide useful information on U.S. and Russian space flights so reporters and producers will not be forced to rely on government or industry public affairs officers at times when it might be difficult to get timely responses. All of these data are available elsewhere, of course, but not necessarily in one place. The STS-127 version of the CBS News Space Reporter's Handbook was compiled from NASA news releases, JSC flight plans, the Shuttle Flight Data and In-Flight Anomaly List, NASA Public Affairs and the Flight Dynamics office (abort boundaries) at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. -

WENDY B. LAWRENCE (CAPTAIN, USN) NASA ASTRONAUT (FORMER) PERSONAL DATA: Born July 2, 1959, in Jacksonville, Florida

Biographical Data Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 National Aeronautics and Space Administration WENDY B. LAWRENCE (CAPTAIN, USN) NASA ASTRONAUT (FORMER) PERSONAL DATA: Born July 2, 1959, in Jacksonville, Florida. EDUCATION: Graduated from Fort Hunt High School, Alexandria, Virginia, in 1977; received a bachelor of science degree in ocean engineering from U.S. Naval Academy in 1981; a master of science degree in ocean engineering from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in 1988. ORGANIZATIONS: Phi Kappa Phi; Association of Naval Aviation; Women Military Aviators; Naval Helicopter Association. SPECIAL HONORS: Awarded the Defense Superior Service Medal, the Defense Meritorious Service Medal, the NASA Space Flight Medal, the Navy Commendation Medal and the Navy Achievement Medal. Recipient of the National Navy League’s Captain Winifred Collins Award for inspirational leadership (1986). EXPERIENCE: Lawrence graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1981. A distinguished flight school graduate, she was designated as a naval aviator in July 1982. Lawrence has more than 1,500 hours flight time in six different types of helicopters and has made more than 800 shipboard landings. While stationed at Helicopter Combat Support Squadron SIX (HC-6), she was one of the first two female helicopter pilots to make a long deployment to the Indian Ocean as part of a carrier battle group. After completion of a master’s degree program at MIT and WHOI in 1988, she was assigned to Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron Light THIRTY (HSL-30) as officer-in-charge of Detachment ALFA. In October 1990, Lawrence reported to the U.S. -

How Do You Sneeze in a Spacesuit? Very Carefully 21 July 2009, by MIKE SCHNEIDER , Associated Press Writer

How do you sneeze in a spacesuit? Very carefully 21 July 2009, By MIKE SCHNEIDER , Associated Press Writer posts were played one at a time for commander Mark Polansky, pilot Doug Hurley, Canadian astronaut Julie Payette and Wolf, who took turns answering the questions live, more than 200 miles above Earth. Other questioners asked the astronauts what they missed most in space (friends and family), what they did in their spare time (look out the window) and what would happen if the shuttle or space station flew into a black hole (don't know). There are currently 13 crew members at the space station In this 19 July 2009 photo provided by NASA shows - seven visiting from the shuttle and six living at the Canadian Space Agency astronaut Julie Payette float station. onto the mid deck of the space shuttle Endeavour, where she joins astronaut Dave Wolf, who makes an The YouTube questions were the latest effort by entry on a laptop computer. The two STS-127 mission NASA to embrace social media. Polansky has a specialists are part of a seven member shuttle crew Twitter account with more than 37,500 followers, currently visiting the International Space Station, which and since the mission began last Wednesday, is now docked with the shuttle. (AP Photo/NASA) Polansky has tweeted regularly with the help of workers at the Johnson Space Center who actually post his messages. (AP) -- When it comes to sneezing in a spacesuit Last May, under the moniker Astro-Mike, Astronaut during a spacewalk in the void of space, it is best Mike Massimino became the first person to tweet to aim well. -

Phase 1 Program Joint Report

Section 7 - Crew Training Authors: Aleksandr Pavlovich Aleksandrov, Co-Chair, Crew Training and Exchange Working Group (WG) Yuri Petrovich Kargopolov, Co-Chair, Crew Training and Exchange WG William C. Brown, Co-Chair, Crew Training and Exchange WG Tommy Capps, Crew Training and Exchange WG Working Group Members and Contributors: Yuri Nikolayevich Glaskov, Deputy Chief, GCTC Richard Fullerton, Co-Chair, Extravehicular Activity (EVA) WG Shannon Lucid, Astronaut Representative for the Crew Training and Exchange WG Jeffery Cardenas, Co-Chair, Mir Operations and Integration Working Group (MOIWG) 143 7.1 Overview of Crew Training Working Group 5 – crew exchange and training – was a small group that consisted of two people from the Russian side (A. Alexandrov, Y. Kargopolov) and the American side (Don Puddy, through mid 1995, C. Brown, mid 1995-Present, and T. Capps). The objectives of the group were to determine the duties and responsibilities of cosmonauts and astronauts when completing flights on the Shuttle and Soyuz vehicles and the Mir station, the content of crew training in Russian and in the U.S., and to developing training schedules and programs. The group maintained a fairly standard work process. Periodic meetings were usually held alternating in Russia and in the U.S. Between meetings contact was maintained through the use of teleconferences and faxes. To widen the operational interaction on joint flight training issues, a Johnson Space Center (JSC) office (NASA) was created at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center (GCTC) where an American representative permanently worked. This position, which was called the “Director of Operation, Russia” (DOR) was filled by a representative from the astronaut corps. -

Increasing Crew Capabilities STS- 112/9A Shuttle Press

Expanding the Station Backbone/ Increasing Crew Capabilities STS- 112/9A Shuttle Press Kit WWW.SHUTTLEPRESSKIT.COM Updated September 5, 2002 STS-112 Shuttle Press Kit National Aeronautics and Space Administration Table of Contents Mission Overview ..................................................................................................... 1 Timeline Overview ................................................................................................... 7 Mission Objectives ................................................................................................ 12 Mission Profile ....................................................................................................... 13 Crewmembers ........................................................................................................ 15 Rendezvous and Docking ..................................................................................... 24 Spacewalks STS-112 Extravehicular Activities ............................................................................ 27 Payloads Payload Overview..................................................................................................... 35 S1 Truss .................................................................................................................. 39 International Space Station S1 and P1 Truss Summary .......................................... 42 Crew and Equipment Translation Aid Cart A ........................................................... 45 Spatial Heterodyne Imager for