Australian Solar Eclipse Expeditions: the Voyage to Cape York in 1871

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 Sydney Harbour: Its Diverse Biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings

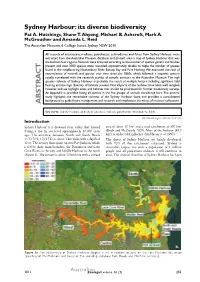

Sydney Harbour: its diverse biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings, Shane T. Ahyong, Michael B. Ashcroft, Mark A. McGrouther and Amanda L. Reid The Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010 All records of crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms and fishes from Sydney Harbour were extracted from the Australian Museum database, and plotted onto a map of Sydney Harbour that was divided into four regions. Records were analysed according to the number of species, genera and families present and over 3000 species were recorded, approximately double to triple the number of species found in the neighbouring Hawkesbury River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking. We examined the rate of accumulation of records and species over time since the 1860s, which followed a stepwise pattern usually correlated with the research activity of specific curators at the Australian Museum. The high species richness of Sydney Harbour is probably the result of multiple factors including significant tidal flushing and the high diversity of habitats present. Not all parts of the harbour have been well sampled, however, and we highlight areas and habitats that should be prioritised for further biodiversity surveys. An Appendix is provided listing all species in the five groups of animals considered here. The present study highlights the remarkable richness of the Sydney Harbour fauna and provides a consolidated background to guide future management and research, and emphasises the values of museum collections. ABSTRACT Key words: Sydney Harbour, diversity, crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms, fishes http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2012.031 Introduction Sydney Harbour is a drowned river valley that formed area of about 50 km2 and a total catchment of 500 km2 during a rise in sea level approximately 10,000 years (Birch and McCready 2009). -

Social Context

Dreamtime Superhighway: an analysis of Sydney Basin rock art and prehistoric information exchange 3 SOCIAL conteXT While anthropology can help elucidate the complexity of cultural systems at particular points in time, archaeology can best document long-term processes of change (Layton 1992b:9) In the original thesis one chapter was dedicated to the ethnohistoric and early sources for the Sydney region and another to previous regional archaeological research. Since 1994, Valerie Attenbrow has published both her PhD thesis (1987, 2004) and the results of her Port Jackson Archaeological Project (Attenbrow 2002). More recent, extensive open area excavations on the Cumberland Plain done as cultural heritage management mitigations (e.g. JMcD CHM 2005a, 2005b, 2006) have also altered our understanding of the region’s prehistory. As Attenbrow’s Sydney’s Aboriginal Past (2002) deals extensively with ethnohistoric evidence from the First Fleet and early days of the colony the ethnohistoric and historic sources explored for this thesis have been condensed to provide the rudiments for the behavioral model developed for prehistoric Sydney rock art. The British First Fleet sailed through Sydney Heads on 26 January 1788. Within two years an epidemic of (probably) smallpox had reduced the local Aboriginal population significantly – in Farm Cove the group which was originally 35 people in size was reduced to just three people (Phillip 1791; Tench 1793; Collins 1798; Butlin 1983; Curson 1985; although see Campbell 2002). This epidemic immediately and irreparably changed the traditional social organisation of the region. The Aboriginal society around Port Jackson was not studied systematically, in the anthropological sense, by those who arrived on the First Fleet. -

February – March

BMW Sydney, Rushcutters Bay. The legs you see in this picture be ong to John. His job is to make sure when you drive away after a service at BMW Sydney, your car looks as good as the day you drove it off the showroom floor. And we can honestly say, when it comes to detail, no one is as driven as John. Of course, he's not alone. He's only one of five staff dedicated to this sole task. And obviously, we do mean dedicated. It's quite selfish really, but we've always believed that if you look good, so do we. From the way we service your car to the way we serve you a coffee while you wait, it's what makes BMW Sydney a world of BMW. BMW Sydney, 65 Craigend Street, Rushcutters Bay. 9334 4555. www.bmwsydney.com.au 1999 Telstra Sydney to Hobart A TIME TO REMEMBER 4 In the fastest race in 55 years, the Volvo 60 Nokia, a Danish/Australian entry, slashed the record for the Telstra Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race while 15 other yachts also broke Morning Glory's time. YES TO YENDYS 8 IMS Overall winner of the 1999 Telstra Sydney to Hobart, the Farr 49 Yendys, had raced for only nine days , including the Hobart, when she crossed the line on the Derwent River to clinch victory for owner/skipper Geoffrey Ross. TAILENDING THE FLEET 12 The story of the race aboard the 22-year-old 33-footer Berrimilla, the last yacht to complete the race to Hobart, taking seven days 10 hours and logging 920 nautical miles for the rhumbline course of 630 mile. -

MIDDLE HEAD As a NSW DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION FIELD STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL CENTRE

MIDDLE HEAD as a NSW DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION FIELD STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL CENTRE The NSW Department of Education has 22 Environmental Education Centres offering curriculum based field work experiences to help students and teachers in a wide variety of subjects. The Centres deliver innovative and contextually relevant teaching and learning programs. Programs are tailored to fit the needs of students and the curriculum These centres usually cater for all NSW Department of Education Schools K-12. My late husband, Donald Henry Goodsir OAM, worked for the Education Department for over 40 years and was the Director of Schools responsible for Environmental Education at one stage in his career. He personally established 3 such Field Studies Centres – the Warrumbungle Centre outside of Coonabarabran, Botany Bay and Observatory Hill. Each Field Study Centre is unique and located in a specific environment. A Middle Head location would offer students from all of NSW an opportunity to focus especially on the early settlement of Sydney Harbour, Australia’s military history, indigenous culture, Sydney Harbour’s marine environment and geography. This would be particularly beneficial for students from the western suburbs and country locations. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As a trained teacher of Geography and History working with the NSW Department of Education for over 30 years, I can recognize the enormous educational potential of this Middle Head site to allow students to physically walk through time. It is a ready-made indoor/outdoor classroom covering a range of curriculum areas. The educational benefits for all students arising from such an experience would be invaluable especially to those who live far removed from this area. -

Dawes Point Geographical Review

Dawes Point Geographical Review To the Royal Australian Historical Society, Geographical Society of NSW, and the Geographical Names Board of NSW From Davina Jackson PhD, M.Arch, FRGS, MRAHS 19 February 2018 Synopsis Leading Sydney historians have noted persistent confusions about the appropriate mapping of Dawes Point—as several places of colonial history significance and a suburb gazetted in 1993. This report suggests that Lt. William Dawes’s science, defence, construction and linguistic contributions to colonial Sydney would be appropriately honoured by: —Recognising Dawes Point as all the public pedestrian areas occupying the western headland of Sydney Cove from the north headland of Campbells Cove to Ives Steps beside Pier 1 on Walsh Bay; —Renaming Hickson Road Reserve as part of the existing Dawes Point Reserve—which also has been identified in state government documents as Dawes Point (Tar ra) Park*; —Including all the Dawes Point public open space area in the suburb of The Rocks (which currently includes only Hickson Road Reserve); —Delisting the microsuburb of Dawes Point (2016 pop. 357), which since 1993 has overlapped half of the Walsh Bay conservation zone (SREP 16 1989-2009) and parts of the Millers Point and Dawes Point Park conservation zones; and —Including Lower Fort Street (west side) and Trinity Street in the suburb and conservation zone of Millers Point (LEP 2012), to conceptually rejoin Fort Street on Observatory Hill. * See Figs. 30-32 from Mary Knaggs, 2011, Dawes Point (Tar ra) Conservation Management Plan, Sydney: NSW Government Architect’s Office, and earlier Dawes Point CMPs. Summary Dawes Point has been inconsistently mapped since the early 1800s. -

New South Wales from 1810 to 1821

Attraction information Sydney..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Sydney - St. Mary’s Cathedral ..............................................................................................................................................3 Sydney - Mrs Macquarie’s Chair ..........................................................................................................................................4 Sydney - Hyde Park ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Sydney - Darling Harbour .....................................................................................................................................................7 Sydney - Opera House .........................................................................................................................................................8 Sydney - Botanic Gardens ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Sydney - Sydney Harbour Bridge ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Sydney - The Rocks .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Sydney Harbour National Park Plan of Managementdownload

Plan of Management Sydney Harbour National Park 2012 Sydney Harbour National Park Nurture. Understand. Learn. Enjoy. PLAN OF MANAGEMENT 2012 Foreword 6 Middle Head This plan of management describes how the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) will conserve the natural and cultural heritage of the park while providing unique and enriching experiences for visitors to Sydney Harbour. The park is one of the smaller national parks in looking for partners to craft and deliver a range of New South Wales. At just under 400 hectares it sits innovative visitor experiences to complement and within a protected areas system totalling around enhance appreciation of the park. 7 million hectares of land. The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 Though small the park contains an extraordinary requires that a plan of management be prepared diversity of natural and cultural heritage, as well for each national park. A draft plan of management as some of Sydney’s most valued sites for outdoor for Sydney Harbour National Park was placed on recreation, special events and celebrations. public exhibition from 12 December 2010 to 30 April 2011. The submissions received were The park is distinguished by the number and carefully considered before adopting this plan. significance of historic sites around the harbour, including the fortifications at Fort Denison, the This plan contains a number of actions to North Head Quarantine Station, the recreational achieve the NSW 2021 priority to ‘Protect our parklands of Nielsen Park and Shark Island and the native vegetation, biodiversity, land, rivers and mast of the first HMAS Sydney at Bradleys Head. -

Sydney Harbour Superyacht Guidelines

Sydney Harbour superyacht guidelines Guidelines for Masters operating Superyachts on Sydney Harbour Contents Executive Summary 1 Qualifications and registration 9 Port procedures 2 Boat licences and certificates of competency 9 Directions for navigation 2 Registration of vessels 9 Directions and regulations to be observed 2 Protected animals 10 Required charts 2 Approach distances 10 Port services 2 Speed 10 Pilotage requirements 2 Approach directions 10 Wind and weather 3 Action if a marine mammal approaches 11 Port Authority of NSW Vessel Traffic Service 3 Communications 11 Pilot boarding place 3 VHF channels 11 Sydney Harbour – general considerations 3 Important contact details 11 General 3 Useful websites 12 Speed limits 3 Photographs 13 Speed restricted areas 4 Anzac Bridge 13 Conduct within Sydney Harbour 7 Rozelle Bay Superyacht Marina 13 Prohibited areas for general navigation 7 Campbells Cove 14 General 7 Sydney Cove – Circular Quay 15 Restricted access areas 7 Fort Denison 15 Collision or incident reports 8 Garden Island Naval Base 15 Berthing at commercial wharves 8 Walsh Bay 16 Pollution, nuisance or danger 8 Sydney Harbour Bridge 17 Marine Pollution Act 1987 8 Jones Bay Wharf, Pyrmont 17 Pump-out facilities 8 Kirribilli Point 17 Garbage 9 Anzac Bridge 18 Causing of nuisance or danger 9 Glebe Island Bridge 18 Farm Cove 18 Wind frequency analyses 19 FRONT COVER PHOTO: ANDREA FRANCOLINI Executive Summary Welcome to Sydney. The aim of these guidelines is to assist superyacht masters Superyachts are free to enter and move around with their preparations for a visit to Sydney Harbour and to Sydney Harbour subject to compliance with the provide a reference document during the visit. -

Sydney: a Saltwater Perspective HOBIE PORTER Sydney: a Saltwater Perspective

HOBIE PORTER Sydney: A Saltwater Perspective HOBIE PORTER Sydney: A Saltwater Perspective 29 November – 14 December 2019 Opening Night & Festive Drinks Friday 29 November, 6pm Hobie Porter’s microscopically detailed landscapes examine the faceted intersections between modern civilisation, Indigenous cultures and the natural environment. The artist’s skilful trompe l’oeil and striking verisimilitude capture a specific place and time hedged by a suspended sense of timelessness and transcendence. Notions of catharsis and emancipation radiate from the sublime formations of his sweeping panoramas, yet lingering below this surface allure are deeper contemplations of environmental pillage and questions of sustainability in the age of the Anthropocene. The artist’s newest series, ‘Sydney: A Saltwater Perspective’, depicts the region of Port Jackson and Sydney’s Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub – known to the Eora people as Saltwater Country. In creating the paintings, Porter has been inspired by the contemporary current of historical revisionism of Indigenous engagement with, and cultivation of, the Australian landscape – led by authors such as Bill Gammage (The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia) and Bruce Pascoe (Dark Emu). ‘These works have inspired me to engage in my own historical revision of Sydney’, he reflects, ‘and to develop a project that might decolonise assumed constructions of place, and to think of the very familiar city of Sydney in a less familiar way’. Overlaying Porter’s vast landscapes are salient fragments from Indigenous natural history, which float, mid-air, like a displaced memory or material dream. The artist is fascinated by the flora and fauna utilised by Aboriginals in the Saltwater region, and how they managed these for a sustainable future. -

Headland Park, One of Sydney’S Most Striking Urban Parklands

Headland Park, one of Sydney’s most striking urban parklands Discover Headland Park Explore this heritage precinct at your own pace and discover the panoramic views, peaceful Georges Head Lookout (Map ref 5) bushland and layered history. Welcome to Headland Park Highlights Artist Precinct Middle Head fortifications* Beaches Stop, Indulge, Unwind Headland Park Tunnels and Gunners Tour • Lower Georges Heights Battery Headland Park Visit the Headland Park Artist Take a dip at Cobblers Beach Even a short stroll can stir an appetite, This tour takes you through two walk through beautiful bushland (Map ref 4F) precinct — a collective of more (Map ref 6B), Obelisk Beach so make sure you stop for refreshment sets of fortifications dating back with magnificent harbour views, • Georges Head Battery (Map ref 4H) than 15 studios with sculptors, (Map ref 5D) and at Clifton Gardens’ when you’re visiting Headland Park: to the 1870s. Hear about the role which now hosts artists, cafés, We acknowledge the Borogegal people, the • Upper Georges Heights painters, potters and photographers beautiful netted beach. (Map ref 1I, 2I) this commanding harbour location restaurants and businesses, with Battery (Map ref 4F) Georges Heights Traditional Owners and Custodians of these lands. (See headlandartists.com). played in the defence of Sydney. plenty of open space to explore. Frenchy’s Café (Map ref 4F) The Sculpture by the Sea Collection * Please be advised that access is Water Sports only available during tours. 3 Read Place In addition to historic underground Visit our website for dates Headland Park incorporates Middle Head, of winning pieces is located Discover the beautiful marine life Tea Room at Gunners Barracks fortifications with gun emplacements and to book. -

Conrad Martens

Conrad Martens Calendar of Events 1801 - 1878 The following list is compiled from Conrad Martens' dated sketches, finished works, account books, letters, and note books; contemporary references to Martens by friends are also included, along with personal biographical details. Key: P - Pencil sketch W/C - Watercolour O - Oil L - Lithograph - Account of Pictures - Biographical - Manuscript material, newspaper items, exhibition information - Lessons 1801 May 7 Conrad Martens born at Crutched Friars, near London ========== 1816 Conrad's father dies. The family moves to Exeter. Conrad begins his studies under Copley Fielding ========== 1824 Chideock 1824 Ilchester Castle, Abbotsbury 1824 ========== 1825 July 15 Hangmans Cliff P 15 Combermartin Church P 15 Near Bassit Waters Mouth P 15 Waters Mouth P 15 View of Hangmans Hill, Combermartin P 16 Near Ilfracombe P 16 Ilfracombe harbour, North Devon P 16 Entrance to Ilfracombe Harbour P 16 Combermartin P 17 Willpier Bay P 18 Combermartin P 22 Near Clovelly P 22 Clovelly Beach P 23 Beach at Lundly Isle P 23 Clovelly Pier P 24 Clovelly P 24 Cliffs at Hartland P 24 Hartland Quay P 24 Hartland Abbey P Card Brea Castle near Redruth, Cornwall 1825 ========== 1826 View of Dulverton, Somersetshire 1826 Dulverton bridge, Somerset On the Barle near Dulverton, Somersetshire 1826 ========== 1827 May Seatown 14 Lyme 23 Lympstone June 24 Chigwell Low, Essex July 25 Part of Plymouth from Hoe 27 Twickenham August 3 Old Cottage Gateway, Mardston Ivy Bridge, Devonshire 1827 Chideock, Dorset 1827 ========== 1828 May 23 Lympstone August Exmouth 18 Lympstone Church September 2 Lympstone November Lympstone Church December Littleham Church 22 Powderham Castle View on the East Lynn, N. -

Heritage Impact Assessment

Middle Head, Mosman Former 10 Terminal Regiment Barracks Buildings & Laundry HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT Image: 1961 aerial showing the former Ten Terminal Regiment barracks buildings, laundry and adjacent parade ground. Source: Harbour Trust Prepared for: Sydney Harbour Federation Trust Prepared by: Lucas, Stapleton, Johnson and Partners Pty. Ltd. The Trust Building, Suite 303/ 151 King Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 9357 4811 Date: 16th November 2020 © Lucas, Stapleton, Johnson and Partners Pty. Ltd. 2020 Executive Summary This Heritage Impact Assessment provides an analysis of a proposal to undertake works at Middle Head, Sydney in association with future public domain improvements. Implementing the future public domain improvements will require the demolition of three (3) weatherboard barracks buildings (Buildings B1, B2 and B3) and one (1) weatherboard laundry (Building B4) that formed part of the 10 Terminal Regiment precinct (previously the 111th Light Anti-aircraft Artillery Battery precinct) located at Middle Head. The former Defence lands at Headland Park, Mosman (which include the Middle Head precinct and the adjoining HMAS Penguin Naval base), are listed together on the Commonwealth Heritage List, under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth.) as Commonwealth Heritage Place No 105541. The Middle Head precinct is under the care and management of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust (Harbour Trust), a Commonwealth government agency. The report has been prepared by Lucas, Stapleton, Johnson & Partners (LSJ) on behalf of the Harbour Trust, as the proponent. This Heritage Impact Assessment is being prepared to form part of an application that the Harbour Trust will refer to the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).