Dawes Point Geographical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Signals of Port Jackson

Colonial Signals of Port Jackson by Ralph Kelly Abstract This lecture is about the role signal flags played in the early colonial life of Sydney. I will look at some remarkable hand painted engraved plates from the 1830s and the information they have preserved as to the signals used in Sydney Harbour. Vexillological attention has usually focused on flags as a form of iden - tity for nations and entities or symbol for a belief or idea, but flags are also used to convey information. When we have turned our attention to signal flags, the focus has been on ship to ship signals 1, but the focus of this paper will be on shore to shore harbour signals and the unique system that developed in early Sydney to provide information on shipping arrivals in the port. These flags played a vital role in the life and commerce of the colony from its foundation until the early 20th Century. The Nicholson Chart The New South Wales Calendar and General Post Office Directory 1832 included infor - mation on the Flagstaff Signals in Sydney, including a coloured hand-painted en - graved chart of the Code of Signals for the Colony. 2 This chart was prepared by John 3 Figure 1. naval signals 1 Nicholson, Harbour Master for Sydney’s Port Jackson. It has come to be known as the Nicholson Chart and is one of the foundation docu - ments of Australian vexillology. 4 The primary significance of the chart to vexillologists has been that this is the earliest known illustration of what was described on the chart as the N.S.W. -

The Management of Sydney Harbour Foreshores Briefing Paper No 12/98

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE The Management of Sydney Harbour Foreshores by Stewart Smith Briefing Paper No 12/98 RELATED PUBLICATIONS C Land Use Planning in NSW Briefing Paper No 13/96 C Integrated Development Assessment and Consent Procedures: Proposed Legislative Changes Briefing Paper No 9/97 ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 0 7313 1622 3 August 1998 © 1998 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, with the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Dr David Clune, Manager .......................... (02) 9230 2484 Dr Gareth Griffith, Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law ...................... (02) 9230 2356 Ms Honor Figgis, Research Officer, Law .............. (02) 9230 2768 Ms Rachel Simpson, Research Officer, Law ............ (02) 9230 3085 Mr Stewart Smith, Research Officer, Environment ....... (02) 9230 2798 Ms Marie Swain, Research Officer, Law/Social Issues .... (02) 9230 2003 Mr John Wilkinson, Research Officer, Economics ....... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/gi/library/publicn.html CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction .................................................... 1 2.0 The Coordination of Harbour Planning ............................... 2 3.0 Defence Force Land and Sydney Harbour ............................. 5 3.1 The Views of the Commonwealth in Relation to Defence Land around Sydney Harbour .......................................... -

Developing the West Head of Sydney Cove

GUNS, MAPS, RATS AND SHIPS Developing the West Head of Sydney Cove Davina Jackson PhD Travellers Club, Geographical Society of NSW 9 September 2018 Eora coastal culture depicted by First Fleet artists. Top: Paintings by the Port Jackson Painter (perhaps Thomas Watling). Bottom: Paintings by Philip Gidley King c1790. Watercolour map of the First Fleet settlement around Sydney Cove, sketched by convict artist Francis Fowkes, 1788 (SLNSW). William Bradley’s map of Sydney Cove, 1788 (SLNSW). ‘Sydney Cove Port Jackson 1788’, watercolour by William Bradley (SLNSW). Sketch of Sydney Cove drawn by Lt. William Dawes (top) using water depth soundings by Capt. John Hunter, 1788. Left: Sketches of Sydney’s first observatory, from William Dawes’s notebooks at Cambridge University Library. Right: Retrospective sketch of the cottage, drawn by Rod Bashford for Robert J. McAfee’s book, Dawes’s Meteorological Journal, 1981. Sydney Cove looking south from Dawes Point, painted by Thomas Watling, published 1794-96 (SLNSW). Looking west across Sydney Cove, engraving by James Heath, 1798. Charles Alexandre Lesueur’s ‘Plan de la ville de Sydney’, and ‘Plan de Port Jackson’, 1802. ‘View of a part of Sydney’, two sketches by Charles Alexandre Lesueur, 1802. Sydney from the north shore (detail), painting by Joseph Lycett, 1817. ‘A view of the cove and part of Sydney, New South Wales, taken from Dawe’s Battery’, sketch by James Wallis, engraving by Walter Preston 1817-18 (SLM). ‘A view of the cove and part of Sydney’ (from Dawes Battery), attributed to Joseph Lycett, 1819-20. Watercolour sketch looking west from Farm Cove (Woolloomooloo) to Fort Macquarie (Opera House site) and Fort Phillip, early 1820s. -

13.0 Remaking the Landscape

12 Chapter 13: Remaking the Landscape 13.0 Remaking the landscape 13.1 Research Question The Conservatorium site is located within one of the most significant historic and symbolic landscapes created by European settlers in Australia. The area is located between the sites of the original and replacement Government Houses, on a prominent ridge. While the utility of this ridge was first exploited by a group of windmills, utilitarian purposes soon became secondary to the Macquaries’ grandiose vision for Sydney and the Governor’s Domain in particular. The later creations of the Botanic Gardens, The Garden Palace and the Conservatorium itself, re-used, re-interpreted and created new vistas, paths and planting to reflect the growing urban and economic importance of Sydney within the context of the British empire. Modifications to this site, its topography and vegetation, can therefore be interpreted within the theme of landscape as an expression of the ideology of colonialism. It is considered that this site is uniquely placed to address this research theme which would act as a meaningful interpretive framework for archaeological evidence relating to environmental and landscape features.1 In response to this research question evidence will be presented on how the Government Domain was transformed by the various occupants of First Government House, and the later Government House, during the first years of the colony. The intention behind the gathering and analysis of this evidence is to place the Stables building and the archaeological evidence from all phases of the landscape within a conceptual framework so that we can begin to unravel the meaning behind these major alterations. -

Rob Stokes MP, Minister for Heritage Today Announced a Program of Special Events, Led by the Historic Houses

Mark Goggin, Director of the Historic Houses Trust of Sydney, Australia: Rob Stokes MP, Minister for NSW, said: “Our special program of events celebrates Heritage today announced a program of special events, the life and work of Governor Arthur Phillip and invites led by the Historic Houses Trust of NSW, to mark the people of all ages to gain insight into the significant Bicentenary of the death of Governor Arthur Phillip on contribution he made to the early colony that has 31 August 1814. shaped the modern nation of Australia.” One of the founders of modern Australia, Governor A memorial bronze bust of Governor Phillip will be Phillip was the Commander of the First Fleet and first installed on First Government House Place at the Governor of New South Wales. Museum of Sydney in a free public event at 11.30am on “Governor Phillip made an outstanding contribution to Thursday 28 August. Sculpted by Jean Hill in 1952 and New South Wales and this Bicentenary is an originally located in First Fleet Park before being moved appropriate moment for the Government to into storage during the renovations of the Museum of commemorate his achievements through a program of Contemporary Art Australia. Sydney Harbour Foreshore events across our cultural institutions and gardens.” Authority has recently undertaken conservation work on said Mr Stokes. the bust. The installation of the bust has been supported with a gift from the Friends of The First The commemorative program includes the installation Government House Site and the Kathleen Hooke of a Phillip memorial bust on First Government House Memorial Trust. -

From Its First Occupation by Europeans After 1788, the Steep Slopes on The

The Rocks The Rocks is the historic neighbourhood situated on the western side of Sydney Cove. The precinct rises steeply behind George Street and the shores of West Circular Quay to the heights of Observatory Hill. It was named the Rocks by convicts who made homes there from 1788, but has a much older name, Tallawoladah, given by the first owners of this country, the Cadigal. Tallawoladah, the rocky headland of Warrane (Sydney Cove), had massive outcrops of rugged sandstone, and was covered with dry schlerophyll forest of pink-trunked angophora, blackbutt, red bloodwood and Sydney peppermint. The Cadigal probably burnt the bushland here to keep the country open. Archaeological evidence shows that they lit cooking fires high on the slopes, and shared meals of barbequed fish and shellfish. Perhaps they used the highest places for ceremonies and rituals; down below, Cadigal women fished the waters of Warrane in bark canoes.1 After the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, Tallawoladah became the convicts’ side of the town. While the governor and civil personnel lived on the more orderly easterm slopes of the Tank Stream, convict women and men appropriated land on the west. Some had leases, but most did not. They built traditional vernacular houses, first of wattle and daub, with thatched roofs, later of weatherboards or rubble stone, roofed with timber shingles. They fenced off gardens and yards, established trades and businesses, built bread ovens and forges, opened shops and pubs, and raised families. They took in lodgers – the newly arrived convicts - who slept in kitchens and skillions. -

Campbells Cove Promenade the Rocks.Indd

STATEMENT OF HERITAGE IMPACT Campbells Cove Promenade, The Rocks November 2017 Issue G CAMPBELLS COVE PROMENADE, THE ROCKS ISSUE DESCRIPTION DATE ISSUED BY A Draft for Review 2/01/16 GM B Issued for DA submission 21/12/16 GM C Draft Response to Submissions 28/06/17 GM D Amended Draft 30/06/17 GM E Finalised for Submission 24/07/2017 GL F Update for Submission 21/09/2017 GM G Amended Masterplan for Submission 07/11/2017 GM GBA Heritage Pty Ltd Level 1, 71 York Street Sydney NSW 2000, Australia T: (61) 2 9299 8600 F: (61) 2 9299 8711 E: [email protected] W: www.gbaheritage.com ABN: 56 073 802 730 ACN: 073 802 730 Nominated Architect: Graham Leslie Brooks - NSW Architects Registration 3836 CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 REPORT OVERVIEW 4 1.2 REPORT OBJECTIVES 5 2.0 HISTORICAL SUMMARY 9 2.1 BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LOCALITY AND SITE 9 3.0 SITE DESCRIPTION 12 3.1 URBAN CONTEXT 12 3.2 VIEWS TO AND FROM THE SITE 12 4.0 ESTABLISHED HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SUBJECT SITE 14 4.1 ESTABLISHED SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ROCKS CONSERVATION AREA 14 4.2 ESTABLISHED SIGNIFICANCE OF CAST IRON GATES & RAILINGS 15 4.3 ESTABLISHED SIGNIFICANCE OF HERITAGE ITEMS IN THE VICINITY OF THE SUBJECT SITE 16 4.4 CURTILAGE ANALYSIS 20 4.5 ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL 22 5.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSAL 23 6.0 ASSESSMENT OF HERITAGE IMPACT 25 6.1 INTRODUCTION 25 6.2 RESPONSE TO SUBMISSIONS 25 6.3 OVERVIEW OF THE POTENTIAL HERITAGE IMPACTS 26 6.4 CONSIDERATION OF THE GUIDELINES OF THE NSW HERITAGE DIVISION 26 6.5 EVALUATION AGAINST THE 2014 CMP POLICIES OF CAMPBELL’S STORES 27 7.0 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 29 7.1 CONCLUSIONS 29 7.2 RECOMMENDATIONS 29 8.0 BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 Campbells Cove Promenade Statement of Heritage Impact November 2017 1.0 • consideration of the objectives and recommendations INTRODUCTION outlined in the Conservation Management Plan for The Campbell’s Stores; • requests further consideration be given to redesigning or relocating the boardwalk to reduce the visual and 1.1 REPORT OVERVIEW heritage impacts to the seawall. -

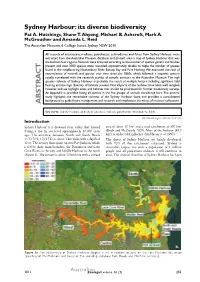

Page 1 Sydney Harbour: Its Diverse Biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings

Sydney Harbour: its diverse biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings, Shane T. Ahyong, Michael B. Ashcroft, Mark A. McGrouther and Amanda L. Reid The Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010 All records of crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms and fishes from Sydney Harbour were extracted from the Australian Museum database, and plotted onto a map of Sydney Harbour that was divided into four regions. Records were analysed according to the number of species, genera and families present and over 3000 species were recorded, approximately double to triple the number of species found in the neighbouring Hawkesbury River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking. We examined the rate of accumulation of records and species over time since the 1860s, which followed a stepwise pattern usually correlated with the research activity of specific curators at the Australian Museum. The high species richness of Sydney Harbour is probably the result of multiple factors including significant tidal flushing and the high diversity of habitats present. Not all parts of the harbour have been well sampled, however, and we highlight areas and habitats that should be prioritised for further biodiversity surveys. An Appendix is provided listing all species in the five groups of animals considered here. The present study highlights the remarkable richness of the Sydney Harbour fauna and provides a consolidated background to guide future management and research, and emphasises the values of museum collections. ABSTRACT Key words: Sydney Harbour, diversity, crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms, fishes http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2012.031 Introduction Sydney Harbour is a drowned river valley that formed area of about 50 km2 and a total catchment of 500 km2 during a rise in sea level approximately 10,000 years (Birch and McCready 2009). -

Social Context

Dreamtime Superhighway: an analysis of Sydney Basin rock art and prehistoric information exchange 3 SOCIAL conteXT While anthropology can help elucidate the complexity of cultural systems at particular points in time, archaeology can best document long-term processes of change (Layton 1992b:9) In the original thesis one chapter was dedicated to the ethnohistoric and early sources for the Sydney region and another to previous regional archaeological research. Since 1994, Valerie Attenbrow has published both her PhD thesis (1987, 2004) and the results of her Port Jackson Archaeological Project (Attenbrow 2002). More recent, extensive open area excavations on the Cumberland Plain done as cultural heritage management mitigations (e.g. JMcD CHM 2005a, 2005b, 2006) have also altered our understanding of the region’s prehistory. As Attenbrow’s Sydney’s Aboriginal Past (2002) deals extensively with ethnohistoric evidence from the First Fleet and early days of the colony the ethnohistoric and historic sources explored for this thesis have been condensed to provide the rudiments for the behavioral model developed for prehistoric Sydney rock art. The British First Fleet sailed through Sydney Heads on 26 January 1788. Within two years an epidemic of (probably) smallpox had reduced the local Aboriginal population significantly – in Farm Cove the group which was originally 35 people in size was reduced to just three people (Phillip 1791; Tench 1793; Collins 1798; Butlin 1983; Curson 1985; although see Campbell 2002). This epidemic immediately and irreparably changed the traditional social organisation of the region. The Aboriginal society around Port Jackson was not studied systematically, in the anthropological sense, by those who arrived on the First Fleet. -

Fort Phillip Archeaology Programs on Observatory Hill

FORT PHILLIP ARCHEAOLOGY PROGRAMS ON OBSERVATORY HILL Using real world learning experiences that incorporate the methods and practices of archaeologists today, your students will investigate, analyse and interpret the many layers of history on Observatory Hill, formerly the location of Fort Phillip. The curriculum-linked programs have been designed around the recent archaeological site investigations. Suitable for students in Years K – 6 HSIE and Mathematics, Years 7–10 History and Year 11 Ancient History. Cost: $10 per student ($9 for combined astronomy, meteorology, Powerhouse Museum or Rocks Education Network excursion) Duration: 1 hour 30 minutes Bookings: Morning sessions at 10am and afternoon sessions at 12.15pm Group size: Max 45, minimum 15. Special requests in regards to class sizes and start times can usually be accommodated. Primary School programs Explore British colonisation and what artefacts and buildings can tell us about the past. Time detectives: dig it! EARLY STAGE 1 & STAGE 1 (YEARS K–2) Become a hands-on archaeological detective and investigate what the site on which Sydney Observatory now stands was like. Experience a simulated archaeology dig (weather permitting) and explore what life was like for the people who worked and lived on Observatory Hill in the past. Students also make a simple toy just like those made by children who once lived here. Curriculum links: Early Stage 1: HSIE CCES.1, CUES.1, ENES.1, SSES.1 / Mathematics NES1.1, NES1.2, NES1.3, DES1.1, SGES.1, SGES.3SSS Stage1: HSIE CCS1.1, CCS1.2, CUS1.3, ENS1.5, ENS1.6, SSS1.7 / Mathematics WMS1.4, NS1.1, NS1.2, NS1.4, DS1.1, MS1.1, SGS1.1, SGS1.3 Time detectives: British colonisation Stage 2 (years 3–4) Investigate the British colonisation and settlement of Australia and what remains of Fort Phillip built in 1804. -

February – March

BMW Sydney, Rushcutters Bay. The legs you see in this picture be ong to John. His job is to make sure when you drive away after a service at BMW Sydney, your car looks as good as the day you drove it off the showroom floor. And we can honestly say, when it comes to detail, no one is as driven as John. Of course, he's not alone. He's only one of five staff dedicated to this sole task. And obviously, we do mean dedicated. It's quite selfish really, but we've always believed that if you look good, so do we. From the way we service your car to the way we serve you a coffee while you wait, it's what makes BMW Sydney a world of BMW. BMW Sydney, 65 Craigend Street, Rushcutters Bay. 9334 4555. www.bmwsydney.com.au 1999 Telstra Sydney to Hobart A TIME TO REMEMBER 4 In the fastest race in 55 years, the Volvo 60 Nokia, a Danish/Australian entry, slashed the record for the Telstra Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race while 15 other yachts also broke Morning Glory's time. YES TO YENDYS 8 IMS Overall winner of the 1999 Telstra Sydney to Hobart, the Farr 49 Yendys, had raced for only nine days , including the Hobart, when she crossed the line on the Derwent River to clinch victory for owner/skipper Geoffrey Ross. TAILENDING THE FLEET 12 The story of the race aboard the 22-year-old 33-footer Berrimilla, the last yacht to complete the race to Hobart, taking seven days 10 hours and logging 920 nautical miles for the rhumbline course of 630 mile. -

The Convict Ship Hashemy at Port Phillip: a Case Study in Historical Error

The Convict Ship Hashemy at Port Phillip: a Case Study in Historical Error Douglas Wilkie Abstract The story of the convict ship Hashemy arriving at Sydney in June 1849 after being turned away from Melbourne has been repeated by many professional, amateur and popular historians. The arrival of the Hashemy, and subsequent anti-convict protest meetings in Sydney, not only became a turning point in the anti-transportation movement in Australia, but also added to an already existing antagonism on the part of Sydney towards its colonial rival, Port Phillip, or Melbourne. This article will demonstrate that the story of the Hashemy being turned away from Port Phillip is based upon a fallacy; investigates how that fallacy developed and was perpetuated over a period of 160 years; and demonstrates that some politicians and historians encouraged this false interpretation of history, effectively extending the inter-colonial discontent that began in the 1840s into the 20th century and beyond. HIS ARTICLE WILL SHOW that the story of the convict ship Hashemy being turned away from Melbourne and sent to Sydney Tin 1849—an account repeated by many historians—is based upon a fallacy. The article investigates how that fallacy developed and was perpetuated by historians over a period of 160 years, and demonstrates that politicians and historians used this false interpretation of history to feed an enduring antagonism felt by Sydney towards its colonial rival, Port Phillip 31 32 Victorian Historical Journal Vol. 85, No. 1, June 2014 or Melbourne. The wider implications of this case study touch upon the credibility given to historians in their interpretations of historical events.