13.0 Remaking the Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response to Research Design

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION CONSERVATORIUM SITE MACQUARIE STREET, SYDNEY VOLUME 2 : RESPONSE TO RESEARCH DESIGN for NSW DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS & SERVICES JULY 2002 CASEY & LOWE Pty Ltd Archaeology & Heritage _________________________________________________________________ 420 Marrickville Road, Marrickville NSW 2204 Tel: (02) 9568 5375 • Fax: (02) 9572 8409 • E-mail: [email protected] 1 Chapter 11: Research Design 11.0 Research Design The Meaning of the Archaeological Evidence The detailed interpretation of the archaeological evidence is found in the following chapters 12 to 16. This is where the research significance of the archaeology is explored and revealed, giving its meaning within a theoretical and social context. The main research questions that the archaeological evidence allows us to address are:1 1. Pre-European environment (Chapter 12) Evidence pertaining to the topography, geomorphology, vegetation etc. of this site prior to colonisation may contribute to research in the environmental history of the Sydney region, Aboriginal land management practices, historical ecology etc. 2. Remaking the landscape (Chapter 13) The Conservatorium site is located within one of the most significant historic and symbolic landscapes created by European settlers in Australia. The area is located between the sites of the original and replacement Government Houses, on a prominent ridge. While the utility of this ridge was first exploited by a group of windmills, utilitarian purposes soon became secondary to the Macquaries’ grandiose vision for Sydney and the Governor’s Domain in particular. The later creations of the Botanic Gardens, The Garden Palace and the Conservatorium itself, re-used, re-interpreted and created new vistas, paths and plantings to reflect the growing urban and economic importance of Sydney within the context of the British empire. -

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839. Margaret C. Dillon B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) University of Tasmania April 2008 I confirm that this thesis is entirely my own work and contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Margaret C. Dillon. -ii- This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Margaret C. Dillon -iii- Abstract This thesis examines the lives of the convict workers who constituted the primary work force in the Campbell Town district in Van Diemen’s Land during the assignment period but focuses particularly on the 1830s. Over 1000 assigned men and women, ganged government convicts, convict police and ticket holders became the district’s unfree working class. Although studies have been completed on each of the groups separately, especially female convicts and ganged convicts, no holistic studies have investigated how convicts were integrated into a district as its multi-layered working class and the ways this affected their working and leisure lives and their interactions with their employers. Research has paid particular attention to the Lower Court records for 1835 to extract both quantitative data about the management of different groups of convicts, and also to provide more specific narratives about aspects of their work and leisure. -

Phanfare May/June 2006

Number 218 – May-June 2006 Observing History – Historians Observing PHANFARE No 218 – May-June 2006 1 Phanfare is the newsletter of the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc and a public forum for Professional History Published six times a year Annual subscription Email $20 Hardcopy $38.50 Articles, reviews, commentaries, letters and notices are welcome. Copy should be received by 6th of the first month of each issue (or telephone for late copy) Please email copy or supply on disk with hard copy attached. Contact Phanfare GPO Box 2437 Sydney 2001 Enquiries Annette Salt, email [email protected] Phanfare 2005-06 is produced by the following editorial collectives: Jan-Feb & July-Aug: Roslyn Burge, Mark Dunn, Shirley Fitzgerald, Lisa Murray Mar-Apr & Sept-Oct: Rosemary Broomham, Rosemary Kerr, Christa Ludlow, Terri McCormack, Anne Smith May-June & Nov-Dec: Ruth Banfield, Cathy Dunn, Terry Kass, Katherine Knight, Carol Liston, Karen Schamberger Disclaimer Except for official announcements the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc accepts no responsibility for expressions of opinion contained in this publication. The views expressed in articles, commentaries and letters are the personal views and opinions of the authors. Copyright of this publication: PHA (NSW) Inc Copyright of articles and commentaries: the respective authors ISSN 0816-3774 PHA (NSW) contacts see Directory at back of issue PHANFARE No 218 – May-June 2006 2 Contents At the moment the executive is considering ways in which we can achieve this. We will be looking at recruiting more members and would welcome President’s Report 3 suggestions from members as to how this could be Archaeology in Parramatta 4 achieved. -

Winter 2012 SL

–Magazine for members Winter 2012 SL Olympic memories Transit of Venus Mysterious Audubon Wallis album Message Passages Permanence, immutability, authority tend to go with the ontents imposing buildings and rich collections of the State Library of NSW and its international peers, the world’s great Winter 2012 libraries, archives and museums. But that apparent stasis masks the voyages we host. 6 NEWS 26 PROVENANCE In those voyages, each visitor, each student, each scholar Elegance in exile Rare birds finds islets of information and builds archipelagos of Classic line-up 30 A LIVING COLLECTION understanding. Those discoveries are illustrated in this Reading hour issue with Paul Brunton on the transit of Venus, Richard Paul Brickhill’s Biography and Neville on the Wallis album, Tracy Bradford on our war of nerves business collections on Olympians such as Shane Gould and John 32 NEW ACQUISITIONS Konrads, and Daniel Parsa on Audubon’s Birds of America, Library takes on Vantage point one of our great treasures. Premier’s awards All are stories of passage, from Captain James Cook’s SL French connection Art of politics voyage of geographical and scientific discovery to Captain C THE MAGAZINE FOR STATE LIBRARY OF NSW BUILDING A STRONG ON THIS DAY 34 FOUNDATION MEMBERS, 8 James Wallis’s album that includes Joseph Lycett’s early MACQUARIE STREET FRIENDS AND VOLUNTEERS FOUNDATION Newcastle and Sydney watercolours. This artefact, which SYDNEY NSW 2000 IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY 10 FEATURE New online story had found its way to a personal collection in Canada, BY THE LIBRARY COUNCIL PHONE (02) 9273 1414 OF NSW. -

Correcting Misconceptions About the Names Applied to Tasmania’S Giant Freshwater Crayfish Astacopsis Gouldi (Decapoda: Parastacidae)

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 152, 2018 21 CORRECTING MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT THE NAMES APPLIED TO TASMANIA’S GIANT FRESHWATER CRAYFISH ASTACOPSIS GOULDI (DECAPODA: PARASTACIDAE) by Terrence D. Mulhern (with three plates) Mulhern, T.D. 2018 (14:xii) Correcting misconceptions about the names applied to Tasmania’s Giant Freshwater Crayfsh Astacopsis gouldi (Decapoda:Parastacidae). Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 152: 21–26. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.152.21 ISSN 0080–4703. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Vic 3010, Australia. Email: [email protected] Tasmania is home to around 35 species of freshwater crayfsh, all but three of which are endemic. Among the endemic freshwater crayfsh, there are three large stream-dwelling species: the Giant Freshwater Crayfsh, Astacopsis gouldi – the world’s largest freshwater invertebrate, the medium-sized A. tricornis and smaller A. franklinii. Errors and confusion surrounding the appropriate Aboriginal names for these species, and the origin and history of the scientifc name of Astacopsis gouldi are outlined. Key Words: Tasmanian freshwater crayfsh, giant freshwater lobster, Giant Freshwater Crayfsh, Astacopsis gouldi Aboriginal words, lutaralipina, tayatitja, scientifc names, William Buelow Gould, Charles Gould. INTRODUCTION tribe in the far south. Plomley also lists a further two variants from Joseph Milligan’s later vocabulary: ‘tayatea’ (Oyster Bay) Tasmania is home to three species of large stream-dwelling and ‘tay-a-teh’ (Bruny Island/South) (Milligan 1859). It is freshwater crayfsh assigned to the endemic genus Astacopsis. important to note that these were English transliterations of Of these three species, Astacopsis gouldi Clark, 1936, known Aboriginal words, as heard by the recorders, none of whom commonly as the Giant Freshwater Crayfsh, or ‘lobster’, is were trained linguists, and interpretation of the signifcance the world’s largest freshwater invertebrate. -

Parramatta's Archaeological Landscape

Parramatta’s archaeological landscape Mary Casey Settlement at Parramatta, the third British settlement in Australia after Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island, began with the remaking of the landscape from an Aboriginal place, to a military redoubt and agricultural settlement, and then a township. There has been limited analysis of the development of Parramatta’s landscape from an archaeological perspective and while there have been numerous excavations there has been little exploration of these sites within the context of this evolving landscape. This analysis is important as the beginnings and changes to Parramatta are complex. The layering of the archaeology presents a confusion of possible interpretations which need a firmer historical and landscape framework through which to interpret the findings of individual archaeological sites. It involves a review of the whole range of maps, plans and images, some previously unpublished and unanalysed, within the context of the remaking of Parramatta and its archaeological landscape. The maps and images are explored through the lense of government administration and its intentions and the need to grow crops successfully to sustain the purposes of British Imperialism in the Colony of New South Wales, with its associated needs for successful agriculture, convict accommodation and the eventual development of a free settlement occupied by emancipated convicts and settlers. Parramatta’s river terraces were covered by woodlands dominated by eucalypts, in particular grey box (Eucalyptus moluccana) and forest -

Colonial Signals of Port Jackson

Colonial Signals of Port Jackson by Ralph Kelly Abstract This lecture is about the role signal flags played in the early colonial life of Sydney. I will look at some remarkable hand painted engraved plates from the 1830s and the information they have preserved as to the signals used in Sydney Harbour. Vexillological attention has usually focused on flags as a form of iden - tity for nations and entities or symbol for a belief or idea, but flags are also used to convey information. When we have turned our attention to signal flags, the focus has been on ship to ship signals 1, but the focus of this paper will be on shore to shore harbour signals and the unique system that developed in early Sydney to provide information on shipping arrivals in the port. These flags played a vital role in the life and commerce of the colony from its foundation until the early 20th Century. The Nicholson Chart The New South Wales Calendar and General Post Office Directory 1832 included infor - mation on the Flagstaff Signals in Sydney, including a coloured hand-painted en - graved chart of the Code of Signals for the Colony. 2 This chart was prepared by John 3 Figure 1. naval signals 1 Nicholson, Harbour Master for Sydney’s Port Jackson. It has come to be known as the Nicholson Chart and is one of the foundation docu - ments of Australian vexillology. 4 The primary significance of the chart to vexillologists has been that this is the earliest known illustration of what was described on the chart as the N.S.W. -

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

The Management of Sydney Harbour Foreshores Briefing Paper No 12/98

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE The Management of Sydney Harbour Foreshores by Stewart Smith Briefing Paper No 12/98 RELATED PUBLICATIONS C Land Use Planning in NSW Briefing Paper No 13/96 C Integrated Development Assessment and Consent Procedures: Proposed Legislative Changes Briefing Paper No 9/97 ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 0 7313 1622 3 August 1998 © 1998 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, with the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Dr David Clune, Manager .......................... (02) 9230 2484 Dr Gareth Griffith, Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law ...................... (02) 9230 2356 Ms Honor Figgis, Research Officer, Law .............. (02) 9230 2768 Ms Rachel Simpson, Research Officer, Law ............ (02) 9230 3085 Mr Stewart Smith, Research Officer, Environment ....... (02) 9230 2798 Ms Marie Swain, Research Officer, Law/Social Issues .... (02) 9230 2003 Mr John Wilkinson, Research Officer, Economics ....... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/gi/library/publicn.html CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction .................................................... 1 2.0 The Coordination of Harbour Planning ............................... 2 3.0 Defence Force Land and Sydney Harbour ............................. 5 3.1 The Views of the Commonwealth in Relation to Defence Land around Sydney Harbour .......................................... -

E-Book Code: REAU1036

E-book Code: REAU1036 Written by Margaret Etherton. Illustrated by Terry Allen. Published by Ready-Ed Publications (2007) © Ready-Ed Publications - 2007. P.O. Box 276 Greenwood Perth W.A. 6024 Email: [email protected] Website: www.readyed.com.au COPYRIGHT NOTICE Permission is granted for the purchaser to photocopy sufficient copies for non-commercial educational purposes. However, this permission is not transferable and applies only to the purchasing individual or institution. ISBN 1 86397 710 4 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012 12345678901234 5 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 -

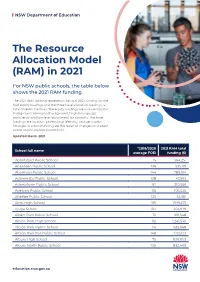

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Developing the West Head of Sydney Cove

GUNS, MAPS, RATS AND SHIPS Developing the West Head of Sydney Cove Davina Jackson PhD Travellers Club, Geographical Society of NSW 9 September 2018 Eora coastal culture depicted by First Fleet artists. Top: Paintings by the Port Jackson Painter (perhaps Thomas Watling). Bottom: Paintings by Philip Gidley King c1790. Watercolour map of the First Fleet settlement around Sydney Cove, sketched by convict artist Francis Fowkes, 1788 (SLNSW). William Bradley’s map of Sydney Cove, 1788 (SLNSW). ‘Sydney Cove Port Jackson 1788’, watercolour by William Bradley (SLNSW). Sketch of Sydney Cove drawn by Lt. William Dawes (top) using water depth soundings by Capt. John Hunter, 1788. Left: Sketches of Sydney’s first observatory, from William Dawes’s notebooks at Cambridge University Library. Right: Retrospective sketch of the cottage, drawn by Rod Bashford for Robert J. McAfee’s book, Dawes’s Meteorological Journal, 1981. Sydney Cove looking south from Dawes Point, painted by Thomas Watling, published 1794-96 (SLNSW). Looking west across Sydney Cove, engraving by James Heath, 1798. Charles Alexandre Lesueur’s ‘Plan de la ville de Sydney’, and ‘Plan de Port Jackson’, 1802. ‘View of a part of Sydney’, two sketches by Charles Alexandre Lesueur, 1802. Sydney from the north shore (detail), painting by Joseph Lycett, 1817. ‘A view of the cove and part of Sydney, New South Wales, taken from Dawe’s Battery’, sketch by James Wallis, engraving by Walter Preston 1817-18 (SLM). ‘A view of the cove and part of Sydney’ (from Dawes Battery), attributed to Joseph Lycett, 1819-20. Watercolour sketch looking west from Farm Cove (Woolloomooloo) to Fort Macquarie (Opera House site) and Fort Phillip, early 1820s.