Diversify: a Fierce, Accessible, Empowering Guide to Why a More Open Society Means a More Successful One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 — 27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

Annual Report 2018

Channel Four Television Corporation Report and Financial Statements 2018 Incorporating the Statement of Media Content Policy Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraph 13(1) of Schedule 3 to the Broadcasting Act 1990 Channel 4 Annual Report 2018 Contents OVERVIEW FINANCIAL REPORT AND STATEMENTS Chair’s Statement 4 Strategic Report Chief Executive’s Statement 8 Financial review and highlights 156 The heart of what we do 13 Our principal activities 159 Remit 38 Key performance indicators 160 At a glance 40 People and corporate annualreport.channel4.com social responsibility 162 STATEMENT OF MEDIA CONTENT POLICY Risk management 164 Strategic and financial outlook 2018 programme highlights 42 and Viability statement 167 4 All the UK 46 Please contact us via our website (channel4.com/corporate) if you’d like this in an alternative Governance format such as Braille, large print or audio. Remit performance The Channel 4 Board 168 Investing in content 48 © Channel Four Television Corporation copyright 2019 Printed in the UK by CPI Colour on Report of the Members 172 Innovation 56 FSC® certified paper. CPI Colour’s Corporate governance 174 The text of this document may be reproduced free environmental management Young people 64 of charge in any format or medium provided that it is Audit Committee Report 179 system is certified to ISO 14001, reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. Inclusion and diversity 70 and is accredited to FSC® chain of Members’ Remuneration Report 183 The material must be acknowledged as Channel Four custody scheme. CPI Colour is a Supporting creative businesses 78 ® Television Corporation copyright and the document certified CarbonNeutral company Talent 84 Consolidated financial statements title specified. -

MY BOOKY WOOK a Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Stand-Up Russell Brand

MY BOOKY WOOK A Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Stand-Up Russell Brand For my mum, the most important woman in my life, this book is dedicated to you. Now for God’s sake don’t read it. “The line between good and evil runs not through states, nor between classes, nor between po liti cal parties either, but through every human heart” Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago “Mary: Tell me, Edmund: Do you have someone special in your life? Edmund: Well, yes, as a matter of fact, I do. Mary: Who? Edmund: Me. Mary: No, I mean someone you love, cherish and want to keep safe from all the horror and the hurt. Edmund: Erm . Still me, really” Richard Curtis and Ben Elton, Blackadder Goes Forth Contents iii Part I 1 April Fool 3 2 Umbilical Noose 16 3 Shame Innit? 27 4 Fledgling Hospice 38 5 “Diddle- Di- Diddle- Di” 50 6 How Christmas Should Feel 57 7 One McAvennie 65 8 I’ve Got a Bone to Pick with You 72 9 Teacher’s Whiskey 8186 94 10 “Boobaloo” 11 Say Hello to the Bad Guy Part II 12 The Eternal Dilemma 105111 13 Body Mist Photographic Insert I 14 Ying Yang 122 131 138146 15 Click, Clack, Click, Clack 16 “Wop Out a Bit of Acting” 17 Th e Stranger v Author’s Note Epigraph vii Contents 18 Is This a Cash Card I See before Me? 159 19 “Do You Want a Drama?” 166 Part III 20 Dagenham Is Not Damascus 179 21 Don’t Die of Ignorance 189 22 Firing Minors 201 Photographic Insert II 23 Down Among the Have-Nots 216 24 First-Class Twit 224 25 Let’s Not Tell Our Mums 239 26 You’re a Diamond 261 27 Call Me Ishmael. -

27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

Rannual Report 2017

T T ANNUAL REPORT RR2017 SS PATRONS PRINCIPAL PATRONS BBC ITV Channel 4 Sky INTERNATIONAL PATRONS A+E Networks International NBCUniversal International Akamai The Walt Disney Company CGTN Turner Broadcasting System Inc Discovery Networks Viacom International Media Networks Facebook YouTube Liberty Global MAJOR PATRONS Accenture ITN Amazon Video KPMG Atos McKinsey and Co Audio Network OC&C Boston Consulting Group Pinewood Studios BT S4C Channel 5 Sargent-Disc Deloitte Sony Endemol Shine STV Group Enders Analysis TalkTalk Entertainment One UKTV Finecast Vice FremantleMedia Virgin Media IBM YouView IMG Studios RTS PATRONS Alvarez & Marsal LLP Raidió Teilifís Éireann Autocue Snell Advanced Media Digital Television Group UTV Television Lumina Search Vinten Broadcast PricewaterhouseCoopers 2 CONTENTS Foreword by RTS Chair and CEO 4 Board of Trustees report to members 6 I Achievements and performance 6 1 Education and skills 8 2 Engaging with the public 16 3 Promoting thought leadership 26 4 Awards and recognition 32 5 The nations and regions 38 6 Membership and volunteers 42 7 Financial support 44 8 Summary of national events 46 9 Centre reports 48 II Governance and finance 58 1 Structure, governance and management 58 2 Objectives and activities 60 3 Financial review 60 4 Plans for future periods 61 5 Administrative details 61 Independent auditor’s report 64 Financial statements 66 Notes to the financial statements 70 Notice of AGM 2018 81 Agenda for AGM 2018 82 Form of proxy 83 Minutes of AGM 2017 84 Who’s who at the RTS 86 3 FOREWORD n 2017, we celebrated our 90th anniversary. It Our bursaries are designed to help improve social was a year marked by a rise in membership, mobility. -

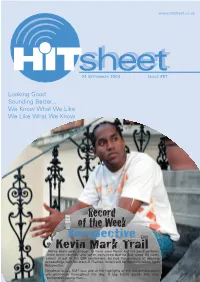

Record of the Week

www.hitsheet.co.uk 24 SEPTEMBER 2004 ISSUE #57 Looking Good Sounding Better... We Know What We Like We Like What We Know Record of the Week Perspective EMI Kevin Mark Trail We’ve been lucky enough to have seen Kevin and his band perform three times recently and we’re convinced that he has some hit tunes comin’ at ya! At the EMI conference, he had the pleasure of opening proceedings with the track D Thames, which will be the likely follow up to Perspective. Needless to say, KMT was one of the highlights of the live performances we witnessed throughout the day. A big future awaits this very personable young man... EDITORIAL 2 EDITORIAL Hello and welcome to issue #57 of the Hit Sheet. It’s that time of year when the industry bustles and buzzes Manchester, do come and say hello. And, if you’re not more than ever. Autumn sales conferences are held, award planning to go anywhere, see the new Metallica movie – ceremonies staged, touring schedules kick off and then watching middle-aged rockers continually admit just how there’s the annual A&R-fest that is In The City. scared and upset they feel is so very Spinal Tap! 31 The Birches, The autumn period arrives as the final few stragglers return London, N21 1NJ from holiday and everything seems to spring back to life at GREG PARMLEY Tel. +44 (0)20 8360 4088 once. True to form, this year has been no exception, Fax: +44 (0)20 8360 4088 starting with the launch of the new Download chart at the Through The Grapevine Email. -

June Sarpong OBE; Director of Creative Diversity at the BBC, Presenter, Award-Winning Author

June Sarpong OBE; Director of Creative Diversity at the BBC, Presenter, Award-Winning Author June has enjoyed a 20‐year career, in which she has become one of the most recognisable faces of British television. June began her career at Kiss 100 and later became a presenter for MTV UK & Ireland. It was when she started on Channel 4’s T4 that she became a household name. June hosted 2005’s Make Poverty History event and presented at the UK leg of Live Earth in 2007. In 2008 she hosted Nelson Mandela’s 90th birthday celebrations in front of 30,000 people in London’s Hyde Park. June has also interviewed and introduced some of the world’s biggest names including HRH Prince of Wales, Bill Clinton, Al Gore and George Clooney. She has worked extensively with HRH Prince Charles as an ambassador for the Prince’s Trust, whilst campaigning for The One and Produce (RED). June was awarded an MBE in 2007 for her services to broadcasting and charity, making her one of the youngest people ever to receive an MBE. June was awarded an OBE in the 2020 New Years’ Honours List. June is the co‐founder of the WIE Network (Women: Inspiration & Enterprise). This acclaimed conference has featured leading speakers including Sarah Brown, Melinda Gates, Arianna Huffington, Donna Karan, Queen Rania, Nancy Pelosi and Iman. After living in America for eight years, June moved back to the UK in 2015, and is now a regular panellist on Sky News’ weekly current affairs discussion show, The Pledge. June is also an author of two award winning books; ‘Diversify: Six Degrees of Integration’ and The Power of Women. -

EVENTS PORTFOLIO LEADERSHIP, MOTIVATIONAL, KEYNOTE & AFTER-DINNER SPEAKERS Triumph HOW CAN YOU DEFY YOUR LIMITS to TRIUMPH?

EVENTS PORTFOLIO LEADERSHIP, MOTIVATIONAL, KEYNOTE & AFTER-DINNER SPEAKERS triumph HOW CAN YOU DEFY YOUR LIMITS TO TRIUMPH? DEFY YOUR LIMITS Sir Bradley Wiggins CBE Britain’s Most Decorated Olympian HOW DO YOU MAINTAIN PEAK OVER 20 YEARS PERFORMANCE FOR OVER 20 YEARS? peak performance Dame Katherine Grainger DBE Britain’s Most Decorated Female Olympian tactics TEAM VICTORY IS STRATEGY WITHOUT TACTICS THE SLOWEST ROUTE TO TEAM VICTORY? Andrew Flintoff MBE Broadcaster and Cricketing Legend mindset and self-belief mindset BREAKING THE BARRIERS OF ADVERSITY ARE MINDSET AND SELF-BELIEF THE KEY TO SUCCESS AND BREAKING THE BARRIERS OF ADVERSITY ON AND OFF THE PITCH? Alex Scott MBE Presenter and Sports Pundit WHAT ROLE DOES family base strong A STRONG FAMILY BASE PLAY BOTH ON AND OFF THE PITCH? Harry and Jamie Redknapp ON AND OFF THE PITCH Football Icons, Father and Son Duo CONSISTENT SUCCESS collaboration and collective intelligence and collective collaboration DOES OPEN COLLABORATION AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE LEAD TO CONSISTENT SUCCESS? Sir Matthew Pinsent CBE Broadcaster and Gold Medal Winning Rower WHAT DIFFERENCES GROWTH CULTURE AND MINDSET ADVANTAGE CAN GROWTH CULTURE performance AND MINDSET ADVANTAGE MAKE TO PERFORMANCE? Matthew Syed Journalist, Author & Broadcaster HOW TO BECOME BRITAIN’S YOUNGEST EVER EUROPEAN professional ever tour youngest TOUR PROFESSIONAL TURNED LEADING GOLFTV PRESENTER? GOLFTV PRESENTER Henni Zuël GOLFTV Presenter and Former Ladies European Tour Professional ACHIEVE YOUR ‘IMPOSSIBLE DREAM’ organisational harmony, -

BBC Creative Diversity Report 2020, Volume 1

2020 VOL.1 YOU CAN’T BE WHAT YOU CAN’T SEE American children’ s rights campaigner Marian Wright Edelman. 2 ,,,.,,,.,,,,,,.,,,.,,, ,,,.,,,.,,, ,,,.,,,.,,, ,,,.,,,.,,, Author’s Note June Sarpong – Director of Creative Diversity One of my favourite quotes of all time is ‘You can’t be what you can’t see’ by the American children’s rights campaigner Marian Wright Edelman. I frst saw Wright Edelman’s powerful words spoken by author Marie Wilson in “Miss Representation”, the award-winning documentary on the portrayal of women in television and flm through the ages. The BBC’s public service remit means that as an organisation we have a commitment to deliver value for every household in the UK. This applies as much to what is seen as to what is heard – and who is seen and heard. This report sets out our plans to make sure more people in the UK are seen and heard, and their value recognised and refected. Across all our services we’ve made important diversity commitments. We’re collaborating across the industry, fnding new ways of working with our suppliers, and BBC television and radio have both pledged signifcant resource to the creation of more representative content for our audiences. The BBC has diversity and inclusion at the heart of its strategy. In this report we also outline the work we’re doing to change our internal culture of and the make-up of our workforce. The Director-General, Tim Davie and the Chief Content Ofcer Charlotte Moore have been clear that diversity and inclusion are mission critical to the BBC’s success. -

Talent Tracking

ON SCREEN AND ON AIR TALENT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE BBC’S APPROACH AND IMPACT A REPORT FOR THE BBC TRUST APPENDIX II – TALENT TRACKING BY OLIVER & OHLBAUM ASSOCIATES APRIL 2008 1 APPENDIX II – TALENT TRACKING The objective was to find how the sources of the various network broadcasters’ talent differ, by genre and in some cases over time. Presenter loyalty to broadcasters would also be shown as a result of the ‘talent tracking’. A BARB database consisting of every strand aired on BBC1, BBC2, ITV1, C4 and Five in 2007 was used to select the relevant strands. Strands with less than 300 annual broadcast hours were not considered for analysis. Strands were chosen from genres that have a strong dependence on the quality and audience appeal of their presenter or lead performer. Hence the genres chosen were: • Entertainment, consisting of sub genres ‘Chat Shows’, ‘Quiz/Game Shows’, ‘Family Shows’ and ‘Panel Shows’ • Factual Documentary, consisting of sub genres ‘History’, ‘Human Interest’, ‘Natural History’, ‘Science/ Medical’ • Lifestyle, consisting of sub genres ‘Cooking’, ‘DIY’ and ‘Homes’ • Comedy, consisting of sub genres ‘Situation Comedy’ and ‘Other Comedy’ The talent analysis would then be taken form these selected strands. In the cases where talent appeared for the same channel on more than one strand, the talent was still only considered once for tracking analysis. If talent appeared on more than one channel, then their tracking would appear in all relevant channel profiles. Various different web-based sources were used to best map out the talent’s career. www.wikipedia.org and www.tv.com have career résumés on most of the selected talent; for a deeper and more comprehensive analysis, www.imdb.com and www.spotlight.com were used as reliable programme and talent databases. -

Channel 4'S 25 Year Anniversary

Channel 4’s 25 year Anniversary CHANNEL 4 AUTUMN HIGHLIGHTS Programmes surrounding Channel 4’s anniversary on 2nd November 2007 include: BRITZ (October) A two-part thriller written and directed by Peter Kosminsky, this powerful and provocative drama is set in post 7/7 Britain, and features two young and British-born Muslim siblings, played by Riz Ahmed (The Road to Guantanamo) and Manjinder Virk (Bradford Riots), who find the new terror laws have set their altered lives on a collision course. LOST FOR WORDS (October) Channel 4 presents a season of films addressing the unacceptable illiteracy rates among children in the UK. At the heart of the season is a series following one dynamic headmistress on a mission to wipe out illiteracy in her primary school. A special edition of Dispatches (Why Our Children Can’t Read) will focus on the effectiveness of the various methods currently employed to teach children to read, as well as exploring the wider societal impact of poor literacy rates. Daytime hosts Richard and Judy will aim to get children reading with an hour-long peak time special, Richard & Judy’s Best Kids’ Books Ever. BRITAIN’S DEADLIEST ADDICTIONS (October) Britain’s Deadliest Addictions follows three addicts round the clock as they try to kick their habits at a leading detox clinic. Presented by Krishnan Guru-Murphy and addiction psychologist, Dr John Marsden, the series will highlight the realities of addiction to a variety of drugs, as well as alcohol, with treatment under the supervision of addiction experts. COMEDY SHOWCASE (October) Channel 4 is celebrating 25 years of original British comedy with six brand new 30-minute specials starring some of the UK’s best established and up and coming comedic talent. -

Diversity and Equal Opportunities in Television In-Focus Report on Ten Major Broadcasters

Diversity and equal opportunities in television In-focus report on ten major broadcasters Publication date: 18 September 2019 Diversity and equal opportunities in television: In-focus report on ten major broadcasters Contents Section 1. Introduction 1 2. How diverse is the BBC? 3 3. How diverse is Channel 4? 19 4. How diverse is ITV? 32 5. How diverse is Sky? 46 6. How diverse is Viacom? 61 7. How diverse are the other five major broadcasters? 74 Diversity and equal opportunities in television: In-focus report on ten major broadcasters 1. Introduction 1.1 This report provides more in-depth data and analysis across each of ten major broadcasters. Sections 2 to 6 report on the main five broadcasters (BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Sky and Viacom, which is the owner of Channel 5), each of which has over 750 employees. These sections should be read in conjunction with the main report. Section 7 reports on the remaining five broadcasters that each have over 500 employees (STV, Turner, Discovery, Perform Investment Ltd and QVC). 1.2 For each of the ten broadcasters we provide an overview of the six protected characteristics for which we collected data, showing profiles for all UK employees across each broadcaster. The infographics in purple show profiles for gender, racial group and disability, for which data provision was mandatory. The infographics in blue show profiles for age, sexual orientation and religion or belief, for which provision was voluntary. This is also the first year we have requested that broadcasters voluntarily submit data for social mobility. Many broadcasters have either not yet begun collecting this data or have only just started, so robust analysis of the UK industry in terms of social mobility is not currently possible.