Near-Coastal Native Grasslands of Northwestern Tasmania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Orchid Society of South Australia

NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY of SOUTH AUSTRALIA NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA JOURNAL Volume 6, No. 10, November, 1982 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. SBH 1344. Price 40c PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian PRESIDENT: Mr J.T. Simmons SECRETARY: Mr E.R. Hargreaves 4 Gothic Avenue 1 Halmon Avenue STONYFELL S.A. 5066 EVERARD PARK SA 5035 Telephone 32 5070 Telephone 293 2471 297 3724 VICE-PRESIDENT: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven COMMITTFE: Mr R. Shooter Mr P. Barnes TREASURER: Mr R.T. Robjohns Mrs A. Howe Mr R. Markwick EDITOR: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven NEXT MEETING WHEN: Tuesday, 23rd November, 1982 at 8.00 p.m. WHERE St. Matthews Hail, Bridge Street, Kensington. SUBJECT: This is our final meeting for 1982 and will take the form of a Social Evening. We will be showing a few slides to start the evening. Each member is requested to bring a plate. Tea, coffee, etc. will be provided. Plant Display and Commentary as usual, and Christmas raffle. NEW MEMBERS Mr. L. Field Mr. R.N. Pederson Mr. D. Unsworth Mrs. P.A. Biddiss Would all members please return any outstanding library books at the next meeting. FIELD TRIP -- CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE The Field Trip to Peters Creek scheduled for 27th November, 1982, and announced in the last Journal has been cancelled. The extended dry season has not been conducive to flowering of the rarer moisture- loving Microtis spp., which were to be the objective of the trip. 92 FIELD TRIP - CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE (Continued) Instead, an alternative trip has been arranged for Saturday afternoon, 4th December, 1982, meeting in Mount Compass at 2.00 p.m. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Partial Flora Survey Rottnest Island Golf Course

PARTIAL FLORA SURVEY ROTTNEST ISLAND GOLF COURSE Prepared by Marion Timms Commencing 1 st Fairway travelling to 2 nd – 11 th left hand side Family Botanical Name Common Name Mimosaceae Acacia rostellifera Summer scented wattle Dasypogonaceae Acanthocarpus preissii Prickle lily Apocynaceae Alyxia Buxifolia Dysentry bush Casuarinacea Casuarina obesa Swamp sheoak Cupressaceae Callitris preissii Rottnest Is. Pine Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia indica supsp. Bidens Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Chenopodiaceae Threlkeldia diffusa Coast bonefruit Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Suada australis Seablite Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Poaceae Sporabolis virginicus Marine couch Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phylliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Poaceae Stipa flavescens Tussock grass 2nd – 11 th Fairway Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Cyperaceae Gahnia trifida Coast sword sedge Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phyliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Central drainage wetland commencing at Vietnam sign Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia halecnomoides Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Poaceae Sporobolis virginicus Cyperaceae Gahnia Trifida Coast sword sedge -

No. 110 MARCH 2002 Price: $5.00

No. 110 MARCH 2002 Price: $5.00 AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Office Bearers President Vice President Barry Conn W.R.(Bill) Barker Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Plant Biodiversity Centre Mrs Macquaries Road Hackney Road Sydney NSW 2000 Hackney SA 5069 tel: (02) 9231 8131 tel: (08) 82229303 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Brendan Lepschi Anthony Whalen Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Australian National Herbarium Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600, Canberra GPO Box 1600, Canberra ACT 2601 ACT 2601 tel: (02) 6246 5167 tel: (02) 6246 5175 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Councillor Councillor Andrew Rozefelds R.O.(Bob) Makinson Tasmanian Herbarium Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney GPO Box 252-40 Mrs Macquaries Road Hobart, Tasmania 7001 Sydney NSW 2000 tel.: (03) 6226 2635 tel: (02) 9231 8111 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Public Officer Annette Wilson Australian Biological Resources Study Environment Australia GPO Box 787 CANBERRA ACT 2601 tel: (02) 6250 9417 email: [email protected] Affiliate Society Papua New Guinea Botanical Society ASBS Web site http://www.anbg.gov.au/asbs Publication dates of previous issue Austral.Syst.Bot.Soc.Nsltr 109 (December 2001 issue) Hardcopy: 15th Jan 2002; ASBS Web site: 15th Jan 2002 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 110 (March 2002) ASBS Inc. Business Council elections with at the Annual General Meeting, which is more than four months after lodgement as A slip for nominations to the next Council is required by the Rules. -

Notes on Grasses (Poaceae) in Hawai‘I: 2

Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 2009 –2010. Edited by Neal L. Evenhuis & Lucius G. Eldredge. Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 110: 17 –22 (2011) Notes on grasses (Poaceae ) in Hawai‘i : 31. neil snoW (Hawaii Biological survey, Bishop museum, 1525 Bernice street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, 96817-2704, Usa; email: [email protected] ) & G errit DaViDse (missouri Botanical Garden, P.o. Box 299, st. louis, missouri 63166-0299, Usa; email: [email protected] ) additional new records for the grass family (Poaceae) are reported for Hawai‘i, including five state records, three island records, one corrected island report, and one cultivated species showing signs of naturalization. We also point out minor oversights in need of cor - rection in the Flora of North America Vol. 25 regarding an illustration of the spikelet for Paspalum unispicatum . Herbarium acronyms follow thiers (2010). all cited specimens are housed at the Herbarium Pacificum (BisH) apart from one cited from the missouri Botanical Garden (mo) for Paspalum mandiocanum, and another from the University of Hawai‘i at mānoa (HaW) for Leptochloa dubia . Anthoxanthum odoratum l. New island record this perennial species, which is known by the common name vernalgrass, occurs natu - rally in southern europe but has become widespread elsewhere (allred & Barkworth 2007). of potential concern in Hawai‘i is the aggressive weedy tendency the species has shown along the coast of British columbia, canada, where it is said to be rapidly invad - ing moss-covered bedrock of coastal bluffs, evidently to the exclusion of native species (allred & Barkworth 2007). the species has been recorded previously on kaua‘i, moloka‘i, maui, and Hawai‘i (imada 2008). -

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests?

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements The Wilderness Society. 2020, Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? The State of the Nation’s RFAs, The Wilderness Society, Melbourne, Australia Table of contents 4 Executive summary Printed on 100% recycled post-consumer waste paper 5 Key findings 6 Recommendations Copyright The Wilderness Society Ltd 7 List of abbreviations All material presented in this publication is protected by copyright. 8 Introduction First published September 2020. 9 1. Background and legal status 12 2. Success of the RFAs in achieving key outcomes Contact: [email protected] | 1800 030 641 | www.wilderness.org.au 12 2.1 Comprehensive, Adequate, Representative Reserve system 13 2.1.1 Design of the CAR Reserve System Cover image: Yarra Ranges, Victoria | mitchgreenphotos.com 14 2.1.2 Implementation of the CAR Reserve System 15 2.1.3 Management of the CAR Reserve System 16 2.2 Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management 16 2.2.1 Maintaining biodiversity 20 2.2.2 Contributing factors to biodiversity decline 21 2.3 Security for industry 22 2.3.1 Volume of logs harvested 25 2.3.2 Employment 25 2.3.3 Growth in the plantation sector of Australia’s wood products industry 27 2.3.4 Factors contributing to industry decline 28 2.4 Regard to relevant research and projects 28 2.5 Reviews 32 3. Ability of the RFAs to meet intended outcomes into the future 32 3.1 Climate change 32 3.1.1 The role of forests in climate change mitigation 32 3.1.2 Climate change impacts on conservation and native forestry 33 3.2 Biodiversity loss/resource decline 33 3.2.1 Altered fire regimes 34 3.2.2 Disease 35 3.2.3 Pest species 35 3.3 Competing forest uses and values 35 3.3.1 Water 35 3.3.2 Carbon credits 36 3.4 Changing industries, markets and societies 36 3.5 International and national agreements 37 3.6 Legal concerns 37 3.7 Findings 38 4. -

BFS048 Site Species List

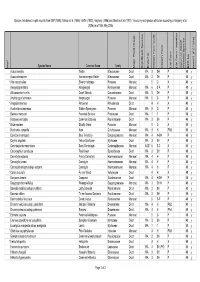

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Intro Outline

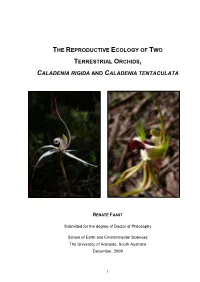

THE REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF TWO TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS, CALADENIA RIGIDA AND CALADENIA TENTACULATA RENATE FAAST Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide, South Australia December, 2009 i . DEcLARATION This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution to Renate Faast and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis (as listed below) resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University's digital research repository, the Library catalogue, the Australasian Digital Theses Program (ADTP) and also through web search engines. Published works contained within this thesis: Faast R, Farrington L, Facelli JM, Austin AD (2009) Bees and white spiders: unravelling the pollination' syndrome of C aladenia ri gída (Orchidaceae). Australian Joumal of Botany 57:315-325. Faast R, Facelli JM (2009) Grazrngorchids: impact of florivory on two species of Calademz (Orchidaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 57:361-372. Farrington L, Macgillivray P, Faast R, Austin AD (2009) Evaluating molecular tools for Calad,enia (Orchidaceae) species identification. -

Flora and Vegetation Values Of

FLORA, VEGETATION AND FAUNA ASSESSMENT OF THE FLAT ROCKS WIND FARM SURVEY AREA Prepared for: Moonies Hill Energy Prepared by: Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd November 2010 Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd MHE1001/113/2010 MATTISKE CONSULTING PTY LTD TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Climate .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Regional Vegetation .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 Clearing of Native Vegetation ............................................................................................................... 3 2.4 Rare and Priority Flora .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.5 Declared Plant Species .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.6 Threatened Ecological Communities (TECs) ........................................................................................ 5 2.7 Local and Regional Significance .......................................................................................................... -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Stormwater Connections to Natural Waterways Rouse Hill Development Area

Stormwater connections to natural waterways Rouse Hill Development Area Overview What This guide explains what you need to do when building a stormwater connection into Sydney Water’s natural open channel waterways in the Rouse Hill Development Area (RHDA). We allow stormwater connections that ensure: stable transition from a constructed drainage system to the natural waterway sustainable water quality management restoration of vegetation following construction. Who This guide applies to owners and developers proposing to build a stormwater pipe connecting to a waterway owned or managed by Sydney Water in the RHDA. This applies to connection proposals for residential, commercial, industrial and other government agencies (e.g. Roads and Maritime Services) developments. Why Construction of stormwater connections to natural waterways affects the waterway and the riparian corridor. This guide ensures that owners and developers design and construct stormwater connections to a safe and sustainable standard by: minimising the number of uncontrolled stormwater discharges ensuring new stormwater connections cause minimal environmental impact to the waterway and its water quality restoring and maintaining disturbed waterfront and riparian vegetation following construction activities. Document current at 31 July 2014 Page 1 Sydney Water – Stormwater connections to natural waterways – Rouse Hill Development Area Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Approval requirements 3 Connecting to any waterway 3 Connecting to a Sydney Water waterway 3 3. Stormwater connection design 4 Point of connection 4 Drainage system 4 Outlet headwall 5 Asset ownership 6 4. Land and vegetation restoration 7 5. Submission requirements 9 6. Design drawings 10 Headwall setback from creek channel – montage 10 Headwall setback from creek channel – plan 11 Headwall setback from creek channel – elevation 12 Headwall setback from creek channel – section 13 Soil horizons – montage 14 Appropriate revegetation – plan and section elevation 15 7. -

Phylogeny of the SE Australian Clade of Hibbertia Subg. Hemistemma (Dilleniaceae)

Phylogeny of the SE Australian clade of Hibbertia subg. Hemistemma (Dilleniaceae) Ihsan Abdl Azez Abdul Raheem School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Adelaide June 2012 The University of Adelaide, SA, Australia Declaration I, Ihsan Abdl Azez Abdul Raheem certify that this work contains no materials which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any universities or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no materials previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University digital research repository, the Library catalogue, the Australian Digital Thesis Program (ADTP) and also through web search engine, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. ii This thesis is dedicated to my loving family and parents iii Acknowledgments The teacher who is indeed wise does not bid you to enter the house of his wisdom but rather leads you to the threshold of your mind--Khalil Gibran First and foremost, I wish to thank my supervisors Dr John G. Conran, Dr Terry Macfarlane and Dr Kevin Thiele for their support, encouragement, valuable feedback and assistance over the past three years (data analyses and writing) guiding me through my PhD candidature.