An International Indigene: Engaging with Brett Graham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

Annual Report 2019/20

Annual Report 2019 – 2020 TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 G19 REPORT OF THE NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION for the year ended 30 June 2020 In accordance with Sections 150 to 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, on behalf of the New Zealand Film Commission we present the Annual Report covering the activities of the NZFC for the 12 months ended 30 June 2020. Kerry Prendergast David Wright CHAIR BOARD MEMBER Image: Daniel Cover Image: Bellbird TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION COVID-19 Our Year in Review ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 The screen industry faced unprecedented disruption in 2020 as a result of COVID-19. At the time the country moved to Alert Level 4, 47 New Zealand screen productions were in various stages Chair’s Introduction •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 of production: some were near completion and already scheduled for theatrical release, some in post-production, many in production itself and several with offers of finance gearing up for CEO Report •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 pre-production. Work on these projects was largely suspended during the lockdown. There were also thousands of New Zealand crew working on international productions who found themselves NZFC Objectives/Medium Term Goals •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 without work while waiting for production to recommence. NZFC's Performance Framework ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 COVID-19 also significantly impacted the domestic box office with cinema closures during Levels Vision, Values and Goals ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 9 3 and 4 disrupting the release schedule and curtailing the length of time several local features Activate high impact, authentic and culturally significant Screen Stories ••••••••••••• 11 played in cinemas. -

Faith Review of Film 3

Union-PSCE, Charlotte Theology and Film Professor Pamela Mitchell-Legg No Juarez, Spring 2010 Faith Review of Film 3 Film Title : Whale Rider Year : 2002 Director : Niki Caro (Based on the book The Whale Rider by Witi Ihimaera) Original release form : Theaters Current Availability and Formats : DVD Genre : Drama, Family Story Elements: Cast: Keisha Castle-Hughes …………………. Paikea Apirana Rawirei Paratene ………………………..Koro Apirana Vicky Haughton ……………………… Nanny Flowers Cliff Curtis……………………………….Porourangi Grant Roa ……………………………….Uncle Rawiri Mana Taumaunu ………………………. Hemi Rachel House ………………………….. Shilo Taungaroa Emile ……………………….Willie Tammy Davis ………………………… Dog Plot Summary: Whale Rider is the story of young the girl Paikea, the newest descendant of the native community called Maori in New Zealand. This community struggles to find its place between their traditions and modernity. Paikea is the survivor of twins. Her brother and mother died the day Paikea was born. The grandfather Koro, the leader of Maori community was hoping for the baby boy to survive in order to make him the new leader of the community but only the girl survived. When the father of Paikea realizes that Koro rejects his granddaughter decides to migrate to Germany leaving her daughter Paikea. Meanwhile, Paikea faces rejection, but finds strength and comfort with her grandmother and searches her place in the community. In order to conserve the traditions of their ancestors, Koro decides to start a school for the boys. Paikea is convinced that she can also learn with the boys of the community but the grandfather does not allow her to be in the school. But soon, with the help of her uncle, Paikea learns all the skills and stories of her ancestors and wins a regional speech contest at her school. -

Whale Rider: the Re-Enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women Kevin V

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 16 Article 9 Issue 2 October 2012 10-1-2012 Whale Rider: The Re-enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women Kevin V. Dodd Watkins College of Art, Design, and Film, [email protected] Recommended Citation Dodd, Kevin V. (2012) "Whale Rider: The Re-enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 16 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol16/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Whale Rider: The Re-enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women Abstract Whale Rider represents a particular type of mythic film that includes within it references to an ancient sacred story and is itself a contemporary recapitulation of it. The movie also belongs to a further subcategory of mythic cinema, using the double citation of the myth—in its original form and its re-enactment—to critique the subordinate position of women to men in the narrated world. To do this, the myth is extended beyond its traditional scope and context. After looking at how the movie embeds the story and recapitulates it, this paper examines the film’s reception. To consider the variety of positions taken by critics, it then analyses the traditional myth as well as how the book first worked with it. The onclusionc is, in distinction to the book, that the film drives a wedge between the myth’s original sacred function to provide meaning in the world for the Maori people and its extended intention to empower women, favoring the latter at the former’s expense. -

Tēnei Marama

Rima 2011 September 2011 I tukuna mai tēnei whakaahua e Ngaumutane Moana Jones nō Rakiamoa. Tēnei marama • Te Korowai announce their proposed strategy for managing the Kaiköura coastline pg 3 • Signing at Te Waihora pg 10 • Executive summary of the annual report pg 25 • Te Awheawhe Rü Whenua reports 12 months on from the September earthquake pg 31 • Date confirmed for annual general meeting pg 42 • Ngäi Tahu Artists create billboards to the theme Te Haka a Rüaumoko pg 47 Nä te Kaiwhakahaere This has been a busy month for environmental In this issue of Te Pānui Rūnaka, we projects. A particular highlight was the signing of the are pleased to announce another rejuvenation program for Te Waihora, Whakaora Te year of strong financial results and Waihora, on Thursday 25 August 2011. In addition, tribal achievements. Environment Canterbury, Ngāi Tahu and Te Waihora Despite the upheavals and Management Board signed an interim co-governance disruptions caused by a year of agreement which establishes a framework for the active significant earthquake events, the management of Te Waihora and its catchment. These end of year results set out in this agreements signal a new approach to management report are extremely pleasing. of natural resources in the region, one which brings These results are a just reward for together the tikanga responsibilities of Ngāi Tahu and the commitment and courage of the statutory responsibilities of Environment Canterbury. our whānau, staff and businesses – when we consider I note also that by the time this edition of Te Pānui the volatility of the global marketplace on top of our Rūnaka is published, Environment Southland and Te regional disaster, then we can all feel very proud of what Ao Marama will have launched the latest State of the has been achieved, not only the financial success but Environment reports for the Murihiku region – in itself most importantly the ongoing sense of unity and shared another important achievement. -

Temuera Morrison MNZM

Profile Temuera Morrison MNZM Vitals Gender Male Age Range 45 - 59 Height 173cm Base Location Auckland Available In Auckland, Christchurch, International, Queenstown, Wellington Skills Actor, Corporate, Presenter, Voice Artist Eye Dark Brown Memberships SAG/AFTRA Agent New Zealand The Robert Bruce Agency Agent Phone +64 (0)9 360 3440 Email [email protected] Agent Web robertbruceagency.com Australian The Robert Bruce Agency (Aus) Agent Phone +61 (0)406 009 477 Email [email protected] Agent Web robertbruceagency.com Credits Type Role Production Company Director 2020 Television Boba Fett The Mandalorian S2 (Post- Fairview Entertainment (US) for Various production) Disney+ Feature Peter Bartlett Occupation Rainfall (Post- Occupation Two Productions Luke Sparke Film production) (AU) 2019 Feature Eddie Jones The Brighton Miracle Eastpool Films (AUS) Max Mannix Film Feature Powell Dora and the Lost City of Gold Paramount Players (US) James Bobin Film Feature Warfield (Voice) Mosley (Animation) Huhu Studios (NZ)/China Film Kirby Atkins Film Animation 2018 Television Te Rangi (4 x eps) Frontier (2016 - ) S3 Take the Shot Productions (CA) Various Feature Peter Bartlett Occupation Sparke Films Luke Sparke Film Copyright © 2020 Showcast. All rights reserved. Page 1 of 7 Feature Tom Curry Aquaman DC Comics James Wan Film 2017 Feature Chief Toi (Voice) Moana (Te Reo Maori) Matewa Media Trust/Walt Ron Clements/John Film Disney Animation Musker Television Jack Te Pania (Voice) Barefoot Bandits - Series 2 Mukpuddy Animation Ryan Cooper, -

Wellington Jazz Among the Discourses

1 OUTSIDE IN: WELLINGTON JAZZ AMONG THE DISCOURSES BY NICHOLAS PETER TIPPING A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 2 Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: Conundrums, questions, contexts ..................................................................... 9 Sounds like home: New Zealand Music ............................................................................... 15 ‘Jazz’ and ‘jazz’...................................................................................................................... 17 Performer as Researcher ...................................................................................................... 20 Discourses ............................................................................................................................ 29 Conundrums ........................................................................................................................ -

Broadcasting Our Reo and Culture

Putanga 08 2008 CELEBRATING MÄORI ACHIEVEMENT Paenga Whäwhä – Haratua Paenga BROADCASTING OUR REO AND CULTURE 28 MÄORI BATTALION WAIKATO MÄORI NETBALL E WHAKANUI ANA I TE MÄORI 10 FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE – LEITH COMER Putanga GOING FORWARD TOGETHER 08 Tënä tätou katoa, Te Puni Kökiri currently has four bills being considered by 2008 Parliament – the Mäori Trustee and Mäori Development Bill, the Stories in Kökiri highlight the exciting and Mäori Purposes Bill (No 2), the Mauao Historic Reserve Vesting Bill inspirational achievement of Mäori throughout and the Waka Umanga (Mäori Corporations) Bill. New Zealand. Kökiri will continue to be a reservoir These bills, along with other Te Puni Kökiri work programmes, Paenga Whäwhä – Haratua Paenga of Mäori achievement across all economic, social highlight Mäori community priorities, including rangatiratanga, and cultural areas. iwi and Mäori identity, and whänau well-being, while The feedback we are getting is very supportive and encompassing government priorities including national identity, positive and it reinforces the continuation of our families – young and old, and economic transformation. Kökiri publication in its current form. We feel sure that the passage of these bills will lead to more Behind the scenes in areas that do not capture much success stories appearing in Kökiri where Mäori have put the public attention is a lot of important and worthwhile legislative changes to good effect in their communities. policy and legislative work that Te Puni Kökiri is intimately involved in. Leith Comer Te Puni Kökiri – Manahautü 2 TE PUNI KÖKIRI | KÖKIRI | PAENGA WHÄWHÄ – HARATUA 2008 NGÄ KAUPAPA 5 16 46 28 Mäori Battalion 5 Waikato 16 Mäori Netball 46 The 28th annual reunion of 28 Mäori In this edition we profi le Aotearoa Mäori Netball celebrated Battalion veterans, whänau and Te Puni Kökiri’s Waikato region – its 21st National Tournament in Te friends was hosted by Te Tairäwhiti’s its people, businesses, successes Taitokerau with a fantastic display of C Company at Gisborne’s Te Poho and achievements. -

Mongrel Media

Mongrel Media Presents BOY A Film by Taika Waititi (90 min., New Zealand, 2011) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html FACT SHEET Title: BOY Writer/Director: Taika Waititi Producers : Ainsley Gardiner, Cliff Curtis, Emanuel Michael Co-Producer : Merata Mita Associate Producer: Richard Fletcher Production Company : Whenua Films, Unison Films In association with : The New Zealand Film Production Fund Trust, The New Zealand Film Commission, NZ On Air, Te Mangai Paho. Running Time : 90 minutes approx Starring : James Rolleston, Te Aho Eketone-Whitu, Taika Waititi Director of Photography : Adam Clark Editor : Chris Plummer Music : The Phoenix Foundation Production Designer : Shayne Radford Hair and Makeup: Danelle Satherley Costume Designer : Amanda Neale Casting: Tina Cleary SHORT SYNOPSIS The year is 1984, and on the rural East Coast of New Zealand “Thriller” is changing kids’ lives. Inspired by the Oscar nominated Two Cars, One Night, BOY is the hilarious and heartfelt coming-of-age tale about heroes, magic and Michael Jackson. BOY is a dreamer who loves Michael Jackson. He lives with his brother ROCKY, a tribe of deserted cousins and his Nan. Boy’s other hero, his father, ALAMEIN, is the subject of Boy’s fantasies, and he imagines him as a deep sea diver, war hero and a close relation of Michael Jackson (he can even dance like him). -

Keynote Speakers

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS 1 Keynote 1 From Maoritanga to Matauranga: Indigenous Knowledge Discourses Linda Tuhiwai Smith (NMM, Cinema) _______________________________________________________________________________ My talk examines the current fascination with matauranga Maori in policy and curriculum. I am interested in the way academic discourses have shifted dramatically to encompass Maori interests and ways of understanding knowledge. I explore some aspects of the development of different approaches to Maori in the curriculum and track the rising interest in matauranga (traditional Maori knowledge) through a period of neoliberal approaches to curriculum in our education system and measurement of research excellence. The Performance Based Research Fund recognises matauranga Maori as a field of research, Government research funds ascribe to a Vision Matauranga policy which must be addressed in all contestable research funds and there are qualifications, majors and subject papers which teach matauranga Maori at tertiary level. New Zealand leads the world in terms of incorporating indigenous knowledge, language and culture into curriculum. Most of the named qualifications are accredited through the New Zealand Qualifications Authority, which then owns the intellectual property of the curriculum. Maori individuals clearly play a significant role in developing the curriculum and resources. They are mostly motivated by wanting to provide a Maori-friendly and relevant curriculum. However, Maori people are also concerned more widely about cultural -

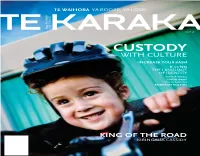

CUSTODY with CULTURE KIRINGAUA CASSIDY INCREASE YOURKA$H the LANGUAGE ROSEMARY Mcleod of IDENTITY TOM BENNION ARIANA TIKAO SIMON KAAN K Vsng 66/9/07 3:06:33 PM / 9

TE WAIHORA YA BOOZE, YA LOSE! KÖANGA $7.95 2007 SPRING issue 36 CUSTODY WITH CULTURE INCREASE YOUR KA$H K vs NG THE LANGUAGE OF IDENTITY ARIANA TIKAO SIMON KAAN TOM BENNION ROSEMARY McLEOD KING OF THE ROAD KIRINGAUA CASSIDY TTK36_ALL.inddK36_ALL.indd 1 66/9/07/9/07 33:06:33:06:33 PPMM FROM THE ACTING CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER, TE RÜNANGA O NGÄI TAHU, ANAKE GOODALL Ahakoa he iti, he pounamu. Although it is small, it is precious. The statistical representation of Mäori is frequently a portrayal of ethnic disparity – Mäori as enjoying, in comparison to Päkehä New Zealand, less health, wealth, education, a greater proclivity for criminal pursuits and perhaps a “warrior gene” or two. The aesthetic of this picture has been consistently unpalatable, routinely criticised and variously addressed. Those in the pakeke bracket have witnessed EDITORIAL TEAM attempts to eradicate disparity through integration, devolution, biculturalism, a Phil Tumataroa Editor (above) Assistant Editor brave new era of “by Mäori for Mäori”, and most recently, the rapid retreat driven by Felolini Maria Ifopo Sub Editor the “needs not race” rhetoric. This quickstep approach to Mäori policy has distorted Stan Darling Debra Farquhar Sub Editor the frame, obscuring the true picture. The pattern emerges not by comparing Mäori to Päkehä, but by contrasting policy against result. CONTRIBUTORS The United Nations recently refocused the picture by tracing the journey between Dr Neville Bennett Tom Bennion cause and effect. The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, as Donald Couch Pirimia Burger indicated by its name, exists to protect and promote the right to racial equality. -

Wai 2700 the CHIEF HISTORIAN's PRE-CASEBOOK

Wai 2700, #6.2.1 Wai 2700 THE CHIEF HISTORIAN’S PRE-CASEBOOK DISCUSSION PAPER FOR THE MANA WĀHINE INQUIRY Kesaia Walker Principal Research Analyst Waitangi Tribunal Unit July 2020 Author Kesaia Walker is currently a Principal Research Analyst in the Waitangi Tribunal Unit and has completed this paper on delegation and with the advice of the Chief Historian. Kesaia has wide experience of Tribunal inquiries having worked for the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since January 2010. Her commissioned research includes reports for Te Rohe Pōtae (Wai 898) and Porirua ki Manawatū (Wai 2200) district inquiries, and the Military Veterans’ (Wai 2500) and Health Services and Outcomes (Wai 2575) kaupapa inquiries. Acknowledgements Several people provided assistance and support during the preparation of this paper, including Sarsha-Leigh Douglas, Max Nichol, Tui MacDonald and Therese Crocker of the Research Services Team, and Lucy Reid and Jenna-Faith Allan of the Inquiry Facilitation Team. Thanks are also due to Cathy Marr, Chief Historian, for her oversight and review of this paper. 2 Contents Purpose of the Chief Historian’s pre-casebook research discussion paper (‘exploratory scoping report’) .................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 4 The Mana Wāhine Inquiry (Wai 2700) ................................................................................. 7